| URVA / KHAIRIZEM - 3 Kazakl'i-yatkan

/ Akcha Khan Kala :

Later Karakalpak name: Kazakl'i-yatkan also spelt Qazaqli-yatqan

Previous Iranian name: Dargash also spelt Darg-ash, Darjash and Darg'ash]

Fourteen kilometres southwest of the Toprak Kala ruins lies the 47 hectare site of Kazakl'i-yatkan, Toprak Kala's apparent predecessor as an administrative centre - if not capital of Khvarizem (Khorezm). Kazakl'i-yatkan is said to be the Dargash mentioned in Persian postmaster Ibn Khordadbegthe's 850 CE writings, where he commented that the capital city of Khorezm had to be moved from Dargash to nearby Kath (modern day Beruni) after the Dargash had been flooded. Kazakl'i-yatkan is not the only candidate as the ancient Dargash. Another candidate is the lost city of Bazar Kala, 32 km north west of To'rtku'l. The earliest parts of the fortress city that have so far been uncovered, date back to the 3rd century BCE, though it is possible that the buildings discovered so far were constructed on older buildings.

The names of the historical sites in the area are all modern names. According to Sue and David Richardson, Kazakl'i-yatkan in Kazakh means the place where Kazakhs are lying down or rest and was a name adopted in the 1930s, when the site was a rest stop for Kazakhs fleeing south from Stalin's enforced collectivization. The older name, Akcha Khan Kala comes from the name of a legendary leader, Akcha Khan.

The site lies just outside the north-western corner of the Tash-k'irman oasis, a former farming region that has now turned into a desert called the Aq Qum Sands. At one time the area was watered by northern arm of a branch of the Amu Darya river - the Akcha Darya river. The flow of water from the Akcha Darya river appears to have been erratic. It could have ceased to flow in the early centuries of the 1st millennium CE only to reform later. A network of canals, the earliest of which date back to the 5th century BCE, were dug to provide a continuous supply of water to the area and were in use until the 8th century CE. However, according to the account of some 10th century CE writers, despite the drying of the Akcha Darya river, the area was flooded by an overflow from the ancient Istemes Lake. At some point, the dried bed of the Akcha Darya formed the Aq Qum Sands desert which today extend for about 30 kilometres northeast Beruni. The northern part of the desert, called the Daganioldi Sands, is where Kazakl'i-yatkan is located.

These sands, which are up to 15 metres deep in places, cover all but the excavated parts of the site up to the top of its outer walls. Consequently from a distance the kala looks like a part of the desert. In many ways, the drying up of the region is a blessing. The sands buried and preserved the ruins in a remarkable condition, and in a manner that could not have been possible with the destructive influences of water, agriculture and human carelessness. A portion of the Akcha Darya river survives as Akcha Ko'l lake north of the Aq Qum Sands.

The square 45 hectare heavily fortified fortress of Kazakl'i-yatkan consists of an older 15-acre (380 by 340 metres) upper enclosure nested in the northern corner of the fortress. The fortress was expanded by adding 30 acres thereby increasing its dimensions to 660 by 700 metres. The newer addition is sometimes called the lower enclosure.

The fortifications of the upper, older enclosure consisted of two complex gateways or barbicans, unfired mud brick double walls roughly 12 metres in height, and regularly spaced towers set on a high plinth or socle made from compacted clay or pakhsa. The use of pakhsa with the consistency of concrete rather than mud brick was at the time a new innovation designed to withstand the impact of a battering ram. The space between the walls housed two levels of galleries from which archers could look down and fire upon attackers. The date of construction is the 3rd to early 2nd century BCE.

Cross section of the double outer walls. Drawing: KA Expedition The roof was supported by wooden columns that rested on stone column bases. The fortifications enclosed what a number buildings including possibly a mausoleum at the centre of the complex, a palace, temple and a temenos, located in the western corner. The temenos was an open rectangular area measuring about 90 by 120 metres, located to the left of the southern entrance. It was bounded on two sides by the outer walls of the citadel and on the other two sides by solid pakhsa walls. The temenos was a sanctuary or sacred space reserved for the political or religious aristocracy. There were also a series of outworks, or proteichisma, along the outer wall. These consisted of a raised and paved covered way and double ditches.

After the construction and use of the proteichisma, the second enclosure was added to the east and south. This too was heavily fortified with galleried curtain walls, regularly spaced towers and a proteichisma.

Between the 1st century BCE and the 1st century CE, a catastrophe occurred at Kazakl'i-yatkan, when a fire ravaged the site, destroying the wooden roof beams of the galleried curtain walls and towers. After the fire, the covered way of the upper enclosure outworks were occupied as living quarters and the towers were reinforced with a cladding of mud bricks and pakhsa. The upper layers in the galleried curtain walls and towers were sealed by mud bricks sometime in the 1st to 2nd century CE and a new cover wall was added. Thereafter, the site was abandoned and the seat of government was moved to Toprak-kala.

The fortress was robbed, probably shortly after it was abandoned. Most of the gold leaf was stripped from mouldings and the stone column bases were taken elsewhere for reuse.

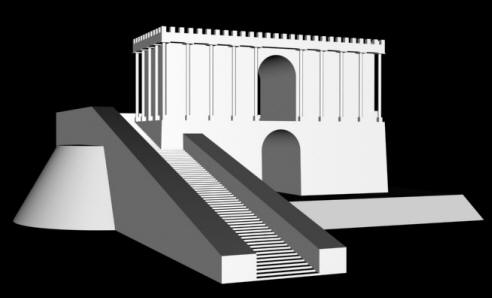

Artist's reconstruction of the central mausoleum Drawing: KA Expedition

The Mausoleum / Fire Temple :

Temple-Palace :

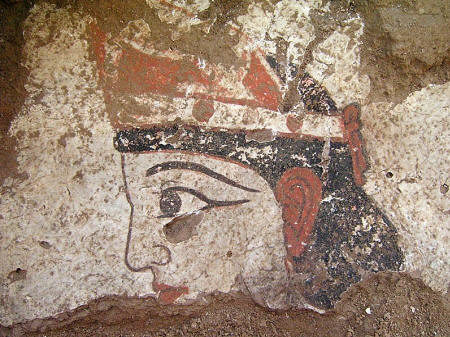

Wall paintings :

Mural example. Photo: KA Expedition While the site has been extensively looted, the painted plaster was of no interest to the looters. Mural art and plaster reliefs have been found across the excavated areas of the building, and is perhaps the best preserved early mural art in Central Asia. Dating methods place a date of the late 1st century BCE for the paintings. Where walls are still standing, there are murals up to two metres in height, and where the walls have collapsed, some decorated plaster still lies where it fell on the floor. Some of the scenes show processions of humans and animals, while others are portraits. Some of the artwork are figurative and ornamental designs with vegetal motifs.

Two of the images show the remains of a crowd scene, so called because of the three faces, all looking towards an unknown object to the right. The dual tone facial skin show a sophisticated painting style.

Excavation :

Tash-K'irman-Tepe / Fire Temple :

Platform at Tash-K'irman-Tepe looking north Photo: KA Expedition Six kilometres east-southeast of Kazakl'i-yatkan is a site that has been identified as a large fire temple complex. The complex features a central platform over 100 metres long, surrounded by pakhsa (compacted clay) walls and filled with sterile sand and mud bricks, the top level of which formed a pavement.

Fire Altar with recessed alcove Photo: KA Expedition The structures constructed on top of the pavement included an intricate system of corridors and rooms, some of which contained altars. An unusual amount of ashes was found at the site. Most of the altars and chambers were open to the sky.

Main Fire Chamber. While most the the altars were housed in open chambers, at the centre of the temple-complex was a chamber with an arched roof. Inside the room, the archaeological team found traces of the original sacred fire. The room was very plain without even mud plaster on the walls and the fire was placed directly on the floor surface.

Main Fire Chamber Photo: KA Expedition The altar was located in the centre of the east wall and faced a niche in the west wall. This room was deliberately deconsecrated and sealed in antiquity, after which the corridors surrounding the chamber were used as storage areas for ash.

Ornamental screen in southern fire chamber Photo: KA Expedition Southern Fire Chamber. To the south of the main fire chamber was a far more elaborate set of rooms, which had originally been one large room with a formal altar. In the original plan, there was a single large room with an altar set in the south wall opposite an alcove in the north wall. The north wall had several recessed blind windows set about the central alcove. At some point, the north wall was remodelled to contain an alcove and two blind windows. In the next remodelling phase, the room was was divided by a narrow mud wall. The wall had a doorway in the centre, flanked by two engaged pakhsa (compacted clay) columns set on stone bases. The wall itself is pierced by circular ventilation holes. The altar consisted of a rectangular mud platform set on a low plinth. There is a decorative niche behind the altar with a series of recesses. A second recessed chamber was constructed to the east of the altar.

On the southern part of the platform are a series of open courts and rooms with a variety of storage areas. Some were found to contain ashes. To the north of the platform was yet another set of rooms with subsidiary altars and ash-filled corridors.

Soundings indicate an earlier structure underneath northeast end of the platform. This structure is substantial in size with large pakhsa walls. It may be an earlier temple complex. South of the platform lay a second complex that is ploughed under and used for agriculture. A series of large storage jars sunk into the ground were uncovered there, together with traces of another platform.

The excavated complex that dates to the 1st to 2nd centuries CE, is but the latest of two superimposed monumental structures at the site. Much of the lower one is buried below the platform, but it has been exposed in areas just outside the upper temple. The lower temple may have been founded several centuries earlier.

As with Kazakl'i-yatkan / Akcha Khan Kala, the excavations at Tash-K'irman-Tepe are being conducted by the Karakalpak-Australian Expedition

Koykrylgan Kala :

Model of Koykrylgan Kala Photo credit: Nukus Museum Koykrylgan Kala (also spelt Qoy Qirilq'an Qala) is an amazing and enigmatic site. Its circular shape is unique. Koykrylgan Kala is a 4th century BCE fortress, but what lay within the fortifications is a mystery. Today, the site lies in a remote part of the surrounding desert. In the 2nd century BCE, the complex was destroyed by fire, was rebuilt and remained in use until the 4th century CE.

Artefacts found at the site include fragments of glazed and richly decorated ceramics, two terracotta statuettes, fragments of painted murals, iron tools and Scythian bronze arrow heads, several ossuaries, and inscriptions written in the Chorasmian dialect of the Aramaic language.

Aerial view of Koykrylgan Kala Image credit: Transoxiana 12 At the centre of the circular complex lies a 10 m high two-storey circular building, with a diameter of 45 m, and a 7 m thick outer wall. 15m away from the central building were the outer fortifications. The entire building was surrounded by a moat.

The ground floor of the central building had eight arched-ceiling chambers, arranged as three interconnected groups. Light for the interior came via downward sloping window shafts that penetrated the six metre thick walls.

The purpose of the building has not been determined. It was not a palace or military complex, not was it a fortified city. It did have a fire temple. There are several candidates for ideas on its possible use, two of which are :

1. Its circular shape, the layout of the rooms, makes a centre for science and astronomy with an observatory one possible option. Zoroastrians had developed a precise calendar based on the stars and the seasons. Determining the seasons and thereby the time for planting crops relied on the calendar being accurate.

2. The surrounding land was once a fertile vine-growing region with a network of canals. The site has murals of a bearded man holding a bunch of grapes and a wine jug, as well as a woman pouring wine from an amphora into a goblet.

3. Just outside the western side of the central building were chambers to house ossuaries, and on the eastern side were chambers used for storage of temple utensils and performance of funerary rites.

4. It could also have been a multipurpose centre.

Koykrylgan Kal is a modern name meaning the fragile or breakable fortress. Whatever calamity brought its use to a close, it was ransacked and looted. Today only the central part of the fortress remains. The surviving walls are severely eroded. Most of the outer wall brick has been removed by locals. Further, the groundwater table is rising beneath the fort bringing with it damaging salt. There is little time left to rescue the site before the desert claims the last of its secrets.

Source :

http://www.heritageinstitute.com/ |