| KINGDOM OF KUSH Part I :

An artist's impression of the Kushite army - to which the archers in the foreground belong - in battle. The kingdom of Kush, situated in northern Africa, flourished between c. 1069 BCE and 350 CE. (From the PC game Total War: Rome II - Desert Kingdoms by the Creative Assembly).

Kingdom of Kush Kush was a kingdom in northern Africa in the region corresponding to modern-day Sudan. The larger region around Kush (later referred to as Nubia) was inhabited c. 8,000 BCE but the Kingdom of Kush rose much later. The Kerma Culture, so named after the city of Kerma in the region, is attested as early as 2500 BCE and archaeological evidence from Sudan and Egypt show that Egyptians and the people of Kush region were in contact from the Early Dynastic Period in Egypt (c. 3150 - c. 2613 BCE) onwards. The later civilization defined as 'Kushite' probably evolved from this earlier culture but was heavily influenced by the Egyptians.

While the history of the overall country is quite ancient, the Kingdom of Kush flourished between c. 1069 BCE and 350 CE. The New Kingdom of Egypt (c. 1570-1069 BCE) was in the final stages of decline c. 1069 BCE, which empowered the Kushite city-state of Napata. The Kushites no longer had to worry about incursions into their territory by Egypt because Egypt now had enough trouble managing itself. They founded the Kingdom of Kush with Napata as its capital, and Kush became the power in the region while Egypt floundered.

Kushite kings became the pharaohs of Egypt’s 25th Dynasty and Kushite princesses dominated the political landscape of Thebes in the position of God’s Wife of Amun. The Kushite king Kashta (c. 750 BCE) was the first to establish himself on the Egyptian throne and appointed his daughter, Amenirdis I, the first Kushite God’s Wife of Amun. He was followed by other great Kushite kings who reigned until the Assyrian invasion of Egypt by Ashurbanipal in 666 BCE.

In c. 590 BCE Napata was sacked by the Egyptian pharaoh Psammeticus II (595-589 BCE) and the capital of Kush was moved to Meroe. The Kingdom of Kush continued on with Meroe as its capital until an invasion by the Aksumites c. 330 CE which destroyed the city and toppled the kingdom. Overuse of the land, however, had already depleted the resources of Kush and the cities would most likely have been abandoned even without the Aksumite invasion. Following this event, Meroe and the dwindling Kingdom of Kush survived another 20 years before its end c. 350 CE.

Name

:

The region of Kush was the main source of gold for the Egyptians, and it is thought that 'Nubia' derived from the Egyptian word for gold, 'nub'. There is another theory, however, which claims that 'Nubia' derives from the people known as the Noba or Nuba who settled there. The Egyptians also knew the land as Ta-Nehsy (“Land of the Black People”). Greek and Roman writers referred to the region as Aethiopia (“Land of the Burnt-Faced Persons”) in reference to the indigenous peoples’ black skin, and the Arab tribes knew it as Bilad al-Sudan (“Land of the Blacks”). It should be noted, however, that these designations may or may not have been referencing the whole region.

Kerma

& Early Kush :

The city centered around a structure known as a deffufa, a fortified religious center created from mud brick and rising to a height of 59 feet (18 meters). Interior passageways and stairs led to an altar on the flat roof where ceremonies were held but what these services entailed is unknown. The largest deffufa (the term means 'pile' or 'to mass') is known today as the Western Deffufa, and there is a smaller one to the east and a third which is even smaller. It is thought these formed a triad of a religious center around which the city then rose and was enclosed by walls.

Western Deffufa Temple, Kerma. By Walter Callens (CC BY) The Kerma Culture is thought to have flourished between c. 2400 - c. 1500 BCE. The Egyptian king Mentuhotep II conquered the region at the beginning of the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE) but Kerma remained a thriving metropolis and was powerful enough by the time of the Second Intermediate Period of Egypt (c. 1782 - c. 1570 BCE) to threaten Egypt in conjunction with the people known as the Hyksos who had established themselves as a political and military power in Egypt’s northern Delta region.

The Kushites of Kerma and the Hyksos engaged in trade with the Egyptians at Thebes until Ahmose I (c. 1570-1544 BCE) drove the Hyksos from Egypt and then marched south to defeat the Kushites. Egyptian campaigns into Kush continued during the reigns of Thutmose I (1520-1492 BCE) and Thutmose III (1458-1425 BCE). The end of the Kerma period is usually given as c. 1500 BCE when Thutmose I attacked the city. Thutmose III then founded the city of Napata after his campaigns which consolidated Egyptian power in the region.

Napata

:

Thutmose III built the great Temple of Amun below the nearby mountain of Jebel Barkal which would remain the most important religious site in the country for the rest of its history, with later Egyptian pharaohs such as Ramesses II (1279-1213 BCE) adding to the Temple of Amun and the city. The priests of Amun, fairly quickly, were exercising the same kind of political power over Kushite rulers that they had with Egyptian kings since the time of the Old Kingdom.

As the New Kingdom declined c. 1069 BCE, however, Napata grew stronger as a political entity independent of Egypt. The priests of Amun in Egypt had been steadily gaining even greater power at Thebes and by the time of the Third Intermediate Period of Egypt (c. 1069-525 BCE) the high priest at Thebes ruled Upper Egypt while the pharaoh ruled Lower Egypt from the city of Tanis.

Egypt’s weakness was Kush’s strength, and the Kingdom of Kush is first dated to c. 1069 BCE when the Kushite kings were able to reign without fear or reference to Egyptian monarchs or policies. Napata was chosen as the capital of the new kingdom which continued to trade with Egypt but were able to expand their commerce now with other nations. Kings at first were still buried at Kerma but eventually the royal necropolis was established at Napata. The kingdom grew steadily until it was powerful enough to take what it wanted from Egypt whenever it pleased, and yet when this time came, they did not enter Egypt as conquerors but as rulers intent on preserving Egyptian culture.

The

25th Dynasty :

His successor, Kashta, held a great admiration for Egyptian culture, importing artifacts from the north and "Egyptianizing" Napata and the Kingdom of Kush. As Egypt declined, and power in Lower Egypt had less and less reach into Upper Egypt, Kashta quietly had his daughter Amenirdis I appointed God’s Wife of Amun at Thebes. He was no doubt able to do this owing to the relationship between the Priests of Amun at Napata and those at Thebes, although no documentation attests to this. The position of God’s Wife of Amun, first established during the Middle Kingdom, had grown in importance to the extent that, by Kashta’s time, a woman holding the position was the female equivalent of the High Priest of Amun and had enormous wealth and political power.

Mummy of Amenirdis by Mark Cartwright (CC BY-NC-SA) Amenirdis I took control of Thebes and then simply claimed rule of Upper Egypt. The princes of Lower Egypt at this time were engaged in their own conflicts with each other and so Kashta arrived at Thebes and declared himself King of Upper and Lower Egypt. Without raising an army or initiating any kind of conflict with the Egyptians, he founded the 25th Dynasty of Egypt under which the country was ruled by a Kushite monarchy. Kashta did not live long after his success, however, and was succeeded by his son Piye (747-721 BCE).

There is no record of the reaction of the princes of Lower Egypt to Kashta’s declaration but they strongly objected to Piye’s efforts to consolidate Kushite rule in the country. Piye did not negotiate with those he saw as rebel princes and marched his army north, conquering all the cities of Lower Egypt, and then returned to Napata. He allowed the conquered kings to retain their thrones, re-establish their authority, and continue on as they had previously; they simply had to acknowledge him as their lord. Piye never ruled Egypt from Thebes and does not seem to have given it much thought after his campaign.

Piye’s brother, Shabaka (721-707 BCE) succeeded him and continued to reign from Napata. The royalty of Lower Egypt again rebelled, however, and Shabaka defeated them. He established Kushite control firmly throughout Lower Egypt all the way to the Delta region. Early 20th-century CE scholars claim that this was a “dark time” for Egypt when Nubian culture supplanted traditional Egyptian values but this cannot in any way be supported. So-called Nubian culture, by this time, was highly Egyptianized and, further, Shabaka admired Egyptian culture as much as his brother and father had. He continued to observe Egyptian policies and respected Egyptian beliefs. He had his son, Haremakhet, appointed High Priest of Amun at Thebes, effectively making him ruler of Egypt, and embarked on a series of building projects and reconstruction efforts throughout the country. Shabaka, far from destroying Egyptian culture, preserved it.

Without raising an army or initiating any kind of conduct , Kashta founded the 35th dynasty of Egypt under which the country was ruled by a Kushite Monarchy.

Shabaka’s younger brother (or nephew), Shebitku (707-690 BCE) succeeded him and began well until he came into conflict with the Assyrians. The Egyptians had maintained a buffer zone between their northern borders and the region of Mesopotamia which had been lost by this time. Kingdoms such as Judah and Israel had now rebelled against domination by the Assyrians of Mesopotamia and Shabaka had given sanctuary to a rebel leader, Ashdod, who had revolted against the Assyrian king Sargon II (722-705 BCE). The 25th Dynasty continued to support these kingdoms against the Assyrians, and this brought the Assyrian army to Egypt under their king Esarhaddon in 671 BCE.

Esarhaddon met the Kushite king Taharqa (c. 690-671 BCE) in battle, defeated him, captured his family and other Kushite and Egyptian nobles, and had them sent back to Nineveh in chains. Taharqa himself managed to escape and fled to Napata. He was succeeded by Tantamani (c. 669-666 BCE) who continued to antagonize the Assyrians and was defeated by Ashurbanipal who conquered Egypt in 666 BCE.

The

Great City of Meroe :

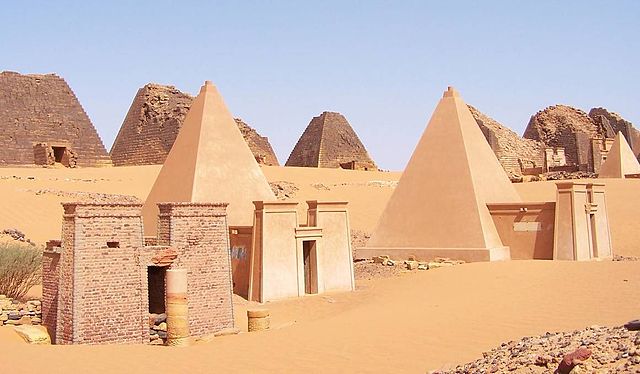

The Pyramids of Meroe by B N Chagny (CC BY-SA) According to the historian Diodorus Siculus (1st century BCE), Arkamani I had been educated in Greek philosophy and refused to be controlled by the superstitions of the priests. He led a band of men to the temple, had all the priests slaughtered, and ended their power over the monarchy. He then instituted new policies and practices which included abandoning Egyptian culture, with an emphasis on Kushite. Arkamani I discarded hieroglyphic script in favor of another known as Meroitic which, to date, has not been deciphered. The fashion of the people of Meroe during his reign shifts away from Egyptian to distinctly Meroitic and the gods of the Egyptians become assimilated into Kushite deities such as Apedemak. The tradition of burying royalty at Napata was also abandoned and kings would thenceforth be entombed at Meroe.

Another interesting innovation of Arkamani I’s reign was the establishment of female monarchs at Meroe. These queens, known as Candaces (also Kandake, Kentake) ruled between c. 284 BCE - c. 314 CE. Although they had male escorts in public ceremonies, they were not subject to male domination. The earliest recorded queen is Shanakdakhete (c. 170 BCE) who is shown in full armor leading her troops in battle. The title of Candace is thought to mean “Queen Mother” but exactly what this refers to is unclear. It may have meant “royal woman” or “mother of the king” initially but the queens who held the title appear as monarchs who were not defined by their relationship with men. One of these queens, Amanirenas (c. 40-10 BCE), led her people successfully through the Meroitic War between Kush and Rome (27-22 BCE) and was able to negotiate favorable terms in the peace treaty from Augustus Caesar.

Timeline

:

Conclusion

:

Large forests rose on the far side of the fertile fields surrounding the city which were irrigated by canals off the Nile. The upper class lived in large houses and palaces which looked down on broad avenues lined with statuary while the lower classes lived in mud-brick homes or huts. According to ancient inscriptions, even the poorest citizen of Meroe was still better off than anyone elsewhere. The Temple of Amun, in the center of the city, was reportedly its jewel and on par with the earlier temple at Napata.

In c. 330 CE the Axumites invaded and sacked Meroe. Although the city would continue on another 20 years, it was effectively destroyed by the Axumites. Even if the invasion had not come, however, Meroe was doomed and had brought this on itself. The iron industry required massive amounts of wood to create charcoal and fuel the furnaces for the iron resulting in deforestation of the once-plentiful forests. The fields were overgrazed by cattle and overused for crops, depleting the soil. Before the Axumites ever arrived, Meroe must have been in decline and would have had to be abandoned anyway. When the last of the people walked away from the city c. 350 CE, the Kingdom of Kush had come to an end.

Part II :

Kingdom of Kush :

Kushite heartland, and Kushite Empire of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt, circa 700 BCE Kingdom

of Kush

c. 1070 BC - c. 350 AD

Capital : Napata, Meroë

Common languages : Meroitic language, Nubian languages, Egyptian, Cushitic

Religion : Ancient Egyptian Religion

Government : Monarchy

Monarch

Historical era : Iron Age to Late Antiquity

•

Established

:

• Capital moved to Meroe : 591 BC

• Disestablished : c. 350 AD

Population

• Meroite phase : 1,150,000

Preceded by

New Kingdom of Egypt

Succeeded by

Alodia

Nobatia

Makuria

Kingdom of Aksum

Today part of : Sudan and Egypt

The Kingdom of Kush was an ancient kingdom in Nubia, centered along the Nile Valley in what is now northern Sudan and southern Egypt.

The region of Nubia was an early cradle of civilization, producing several complex societies that engaged in trade and industry. The city-state of Kerma emerged as the dominant political force between 2450 and 1450 BC, controlling the Nile Valley between the first and fourth cataracts, an area as large as Egypt. The Egyptians were the first to identify Kerma as “Kush" and over the next several centuries the two civilizations engaged in intermittent warfare, trade, and cultural exchange.

Much of Nubia came under Egyptian rule during the New Kingdom period (1550-1070 BC). Following Egypt's disintegration amid the Late Bronze Age collapse, the Kushites reestablished a kingdom in Napata (now modern Karima, Sudan). Though Kush had developed many cultural affinities with Egypt, such as the veneration of Amun, and the royal families of both kingdoms often intermarried, Kushite culture was distinct; Egyptian art distinguished the people of Kush by their dress, appearance, and even method of transportation.

King Kashta ("the Kushite") peacefully became King of Upper and Lower Egypt, while his daughter, Amenirdis, was appointed as Divine Adoratrice of Amun in Thebes. Piye invaded Egypt in the eighth century BC, establishing the Kushite-ruled Twenty-fifth Dynasty. Piye's daughter, Shepenupet II, was also appointed Divine Adoratrice of Amun. The monarchs of Kush ruled Egypt for over a century until the Assyrian conquest, finally being expelled by the Egyptian Psamtik I in the mid-seventh century BC. Following the severing of ties with Egypt, the Kushite imperial capital was located at Meroë, during which time it was known by the Greeks as Aethiopia. The Kingdom of Kush persisted as a major regional power until the fourth century AD when it weakened and disintegrated from internal rebellion. Meroë was captured and destroyed by the Kingdom of Aksum, marking the end of the kingdom and its dissolution into the three polities of Nobatia, Makuria and Alodia.

Long overshadowed by its more prominent Egyptian neighbor, archaeological discoveries since the late 20th century have revealed Kush to be an advanced civilization in its own right. The Kushites had their own unique language and script; maintained a complex economy based on trade and industry; mastered archery; and developed a complex, urban society with uniquely high levels of female participation.

Name : Kush in hieroglyphs

k3š

The native name of the Kingdom was recorded in Egyptian as k3š, likely pronounced [kutu] or [ku?u] in Middle Egyptian, when the term was first used for Nubia, based on the New Kingdom-era Akkadian transliteration as the genitive kusi.

It is also an ethnic term for the native population who initiated the kingdom of Kush. The term is also displayed in the names of Kushite persons, such as King Kashta (a transcription of k3š-t3 "(one from) the land of Kush"). Geographically, Kush referred to the region south of the first cataract in general. Kush also was the home of the rulers of the 25th Dynasty.

The name Kush, since at least the time of Josephus, has been connected with the biblical character Cush, in the Hebrew Bible, son of Ham (Genesis 10:6). Ham had four sons named: Cush, Put, Canaan, and Mizraim (Hebrew name for Egypt). According to the Bible, Nimrod, a son of Cush, was the founder and king of Babylon, Erech, Akkad and Calneh, in Shinar (Gen 10:10). The Bible also makes reference to someone named Cush who is a Benjamite (Psalms 7:1, KJV).

In Greek sources Kush was known as Kous or Aethiopia.

Origins

: Kerma culture

(c.2500 BC – c.1550 BC)

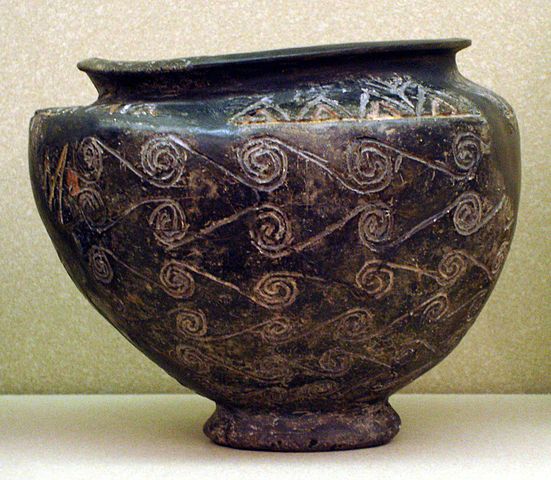

Kerma bowl, 1700 - 1550 BC. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Mirror. End of Kerma Period, 1700 - 1550 BC. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston The Kerma culture was an early civilization centered in Kerma, Sudan. It flourished from around 2500 BC to 1500 BC in ancient Nubia. The Kerma culture was based in the southern part of Nubia, or "Upper Nubia" (in parts of present-day northern and central Sudan), and later extended its reach northward into Lower Nubia and the border of Egypt. The polity seems to have been one of several Nile Valley states during the Middle Kingdom of Egypt. In the Kingdom of Kerma's latest phase, lasting from about 1700–1500 BC, it absorbed the Sudanese kingdom of Sai and became a sizable, populous empire rivaling Egypt.

Egyptian

Nubia (1500 - 1070 BC) :

This eventually resulted in their annexation of Nubia c. 1504 BC. Around 1500 BC, Nubia was absorbed into the New Kingdom of Egypt, but rebellions continued for centuries. After the conquest, Kerma culture was increasingly Egyptianized, yet rebellions continued for 220 years until c. 1300 BC. Nubia nevertheless became a key province of the New Kingdom, economically, politically, and spiritually. Indeed, major pharaonic ceremonies were held at Jebel Barkal near Napata. As an Egyptian colony from the 16th century BC, Nubia ("Kush") was governed by an Egyptian Viceroy of Kush.

Nubian Prince Heqanefer bringing tribute for King Tutankhamun, 18th dynasty, Tomb of Huy. Circa 1342 – c. 1325 BC

Counterweight for a necklace with three images of Hathor, Semna (1390 - 1352 BC), Egyptian Nubia. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Resistance to the early eighteenth Dynasty Egyptian rule by neighboring Kush is evidenced in the writings of Ahmose, son of Ebana, an Egyptian warrior who served under Nebpehtrya Ahmose (1539-1514 BC), Djeserkara Amenhotep I (1514–1493 BC), and Aakheperkara Thutmose I (1493–1481 BC). At the end of the Second Intermediate Period (mid-sixteenth century BC), Egypt faced the twin existential threats—the Hyksos in the North and the Kushites in the South. Taken from the autobiographical inscriptions on the walls of his tomb-chapel, the Egyptians undertook campaigns to defeat Kush and conquer Nubia under the rule of Amenhotep I (1514–1493 BC). In Ahmose's writings, the Kushites are described as archers, "Now after his Majesty had slain the Bedoin of Asia, he sailed upstream to Upper Nubia to destroy the Nubian bowmen." The tomb writings contain two other references to the Nubian bowmen of Kush. By 1200 BC, Egyptian involvement in the Dongola Reach was nonexistent.

Egypt's international prestige had declined considerably towards the end of the Third Intermediate Period. Its historical allies, the inhabitants of Canaan, had fallen to the Middle Assyrian Empire (1365-1020 BC), and then the resurgent Neo-Assyrian Empire (935–605 BC). The Assyrians, from the 10th century BC onwards, had once more expanded from northern Mesopotamia, and conquered a vast empire, including the whole of the Near East, and much of Anatolia, the eastern Mediterranean, the Caucasus and early Iron Age Iran.

Kingdom

of Kush (1070 BC) :

The extent of cultural/political continuity between the Kerma culture and the chronologically succeeding Kingdom of Kush is difficult to determine. The latter polity began to emerge around 1000 BC, 500 years after the end of the Kingdom of Kerma.

The Kushites buried their monarchs along with all their courtiers in mass graves. Archaeologists refer to these practices as the "Pan-grave culture". This was given its name due to how the remains are buried. They would dig a pit and put stones around them in a circle. Kushites also built burial mounds and pyramids, and shared some of the same gods worshiped in Egypt, especially Ammon and Isis. With the worshiping of these gods, the Kushites began to take some of the names of the gods as their throne names.

The Kush rulers were regarded as guardians of the state religion and were responsible for maintaining the houses of the gods. Some scholars [who?] believe the economy in the Kingdom of Kush was a redistributive system. The state would collect taxes in the form of surplus produce and would redistribute to the people. Others believe that most of the society worked on the land and required nothing from the state and did not contribute to the state. Northern Kush seems to have been more productive and wealthier than the Southern area.

Dental trait analysis of fossils dating from the Meroitic period in Semna, in northern Nubia near Egypt, found that they displayed traits similar to those of populations inhabiting the Nile, Horn of Africa, and Maghreb. Traits from mesolithic and southern Nubia around Meroe however indicated a closer affinity with other sub-Saharan dental records. It is indicative of a north-south gradient along the Nile river.

Napatan period (750 - 542 BC) :

Nubian conquest of Egypt (25th Dynasty) :

Statues of various rulers of the late 25th Dynasty–early Napatan period: Tantamani, Taharqa (rear), Senkamanisken, again Tantamani (rear), Aspelta, Anlamani, again Senkamanisken. Kerma Museum

Amun temple of Jebel Barkal, originally built during the Egyptian New Kingdom but greatly enhanced by Piye By the 8th century BC, the new Kushite kingdom emerged from the Napata region of the upper Dongola Reach. The first Napatan king, Alara founded the Napatan, or 25th, Kushite dynasty at Napata in Nubia, now Sudan. Alara dedicated his sister to the cult of Amun at the rebuilt Kawa temple, while temples were also rebuilt at Barkal and Kerma. A Kashta stele at Elephantine, places the Kushites on the Egyptian frontier by the mid-eighteenth century. This first period of the kingdom's history, the 'Napatan', was succeeded by the 'Meroitic', when the royal cemeteries relocated to Meroë around 300 BC.

Alara's successor Kashta extended Kushite control north to Elephantine and Thebes in Upper Egypt. Kashta's successor Piye seized control of Lower Egypt around 727 BC. Piye's 'Victory Stela', celebrating these campaigns between 728-716 BC, was found in the Amun temple at Jebel Barkal. He invaded an Egypt fragmented into four kingdoms, ruled by King Peftjauawybast, King Nimlot, King Iuput II, and King Osorkon IV.

Why the Kushites chose to enter Egypt at this crucial point of foreign domination is subject to debate. Archaeologist Timothy Kendall offers his own hypotheses, connecting it to a claim of legitimacy associated with Jebel Barkal. Kendall cites the Victory Stele of Piye at Jebel Barkal, which states that "Amun of Napata granted me to be ruler of every foreign country," and "Amun in Thebes granted me to be ruler of the Black Land (Kmt)". According to Kendall, "foreign lands" in this regard seems to include Lower Egypt while "Kmt" seems to refer to a united Upper Egypt and Nubia.

Piye's successor, Shabaqo, defeated the Saite kings of northern Egypt between 711-710 BC and installed himself as king in Memphis. He then established ties with Sargon II. Piye's son, Taharqa's army undertook successful military campaigns, as attested by the "list of conquered Asiatic principalities" from the Mut temple at Karnak and "conquered peoples and countries (Libyans, Shasu nomads, Phoenicians?, Khor in Palestine)" from Sanam temple inscriptions. Imperial ambitions of the Mesopotamian based Assyrian Empire made war with the 25th dynasty inevitable. In 701 BC, Taharqa and his army aided Judah and King Hezekiah in withstanding a siege by King Sennacherib of the Assyrians (2 Kings 19:9; Isaiah 37:9). There are various theories (Taharqa's army, disease, divine intervention, Hezekiah's surrender) as to why the Assyrians failed to take the city and withdrew to Assyria. Torok mentions that Egypt's army "was beaten at Eltekeh" under Taharqa's command, but "the battle could be interpreted as a victory for the double kingdom", since Assyria did not take Jerusalem and "retreated to Assyria."

Pyramids of Nuri, built between the reigns of Taharqa (circa 670 BC) and Nastasen (circa 310 BC) The power of the 25th Dynasty reached a climax under Taharqa. The Nile valley empire was as large as it had been since the New Kingdom. New prosperity revived Egyptian culture. Religion, the arts, and architecture were restored to their glorious Old, Middle, and New Kingdom forms. The Nubian pharaohs built or restored temples and monuments throughout the Nile valley, including Memphis, Karnak, Kawa, and Jebel Barkal. It was during the 25th dynasty that the Nile valley saw the first widespread construction of pyramids (many in modern Sudan) since the Middle Kingdom. The Kushites developed their own script, the Meroitic alphabet, which was influenced by Egyptian writing systems c. 700–600 BC, although it appears to have been wholly confined to the royal court and major temples.

Assyrian conquest of Egypt :

Taharqa initially defeated the Assyrians when war broke out in 674 BC. Yet, in 671 BC, the Assyrian King Esarhaddon started the Assyrian conquest of Egypt, took Memphis, and Taharqo retreated to the south, while his heir and other family members were taken to Assyria as prisoners. However, the native Egyptian vassal rulers installed by Esarhaddon as puppets were unable to effectively retain full control, and Taharqa was able to regain control of Memphis. Esarhaddon's 669 BC campaign to once more eject Taharqa was abandoned when Esarhaddon died in Palestine on the way to Egypt. Yet, Esarhaddon's successor, Ashurbanipal, did defeat Taharqa, and Taharqa died soon after in 664 BCE.

Taharqa's successor, Tantamani sailed north from Napata, through Elephantine, and to Thebes with a large army to Thebes, where he was "ritually installed as the king of Egypt." From Thebes, Tantamani began his reconquest and regained control of Egypt, as far north as Memphis. Tantamani's dream stele states that he restored order from the chaos, where royal temples and cults were not being maintained. After defeating Sais and killing Assyria's vassal, Necho I, in Memphis, "some local dynasts formally surrendered, while others withdrew to their fortresses." Tantamani proceeded north of Memphis, invading Lower Egypt and, besieged cities in the Delta, a number of which surrendered to him. [citation needed] The Assyrians, who had a military presence in the Levant, then sent a large army southwards in 663 BC. Tantamani was routed, and the Assyrian army sacked Thebes to such an extent it never truly recovered. Tantamani was chased back to Nubia, but his control over Upper Egypt endured until c. 656 BC. At this date, a native Egyptian ruler, Psamtik I son of Necho, placed on the throne as a vassal of Ashurbanipal, took control of Thebes.The last links between Kush and Upper Egypt were severed after hostilities with the Saite kings in the 590s BC.

The Kushites used the animal-driven water wheel to increase productivity and create a surplus, particularly during the Napatan-Meroitic Kingdom.

Achaemenid period :

Kushite delegation on a Persian relief from the Apadana palace (c. 500 BC) Herodotus mentioned an invasion of Kush by the Achaemenid ruler Cambyses (c. 530 BC). By some accounts Cambyses succeeded in occupying the area between the first and second Nile cataract, however Herodotus mentions that "his expedition failed miserably in the desert." Achaemenid inscriptions from both Egypt and Iran include Kush as part of the Achaemenid empire. For example, the DNa inscription of Darius I (r. 522–486 BC) on his tomb at Naqsh-e Rustam mentions Kušiya (Old Persian cuneiform: pronounced Kushiya) among the territories being "ruled over" by the Achaemenid Empire. Derek Welsby states "scholars have doubted that this Persian expedition ever took place, but... archaeological evidence suggests that the fortress of Dorginarti near the second cataract served as Persia's southern boundary."

Meroitic

period (542 BC - 4th century AD) :

Jewelry found on the Mummy of Nubian King Amaninatakilebte (538 - 519 BCE), Nuri pyramid 10. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Gold flower shaped diadem, found in the Pyramid of King Talakhamani (435 - 431 BCE), Nuri pyramid 16. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston In about 300 BC the move to Meroë was made more complete when the monarchs began to be buried there, instead of at Napata. One theory is that this represents the monarchs breaking away from the power of the priests at Napata. According to Diodorus Siculus, a Kushite king, "Ergamenes", defied the priests and had them slaughtered. This story may refer to the first ruler to be buried at Meroë with a similar name such as Arqamani, who ruled many years after the royal cemetery was opened at Meroë. During this same period, the Kushite authority may have extended some 1,500 km along the Nile River valley from the Egyptian frontier in the north to areas far south of modern Khartoum and probably also substantial territories to the east and west.

Ptolemaic

period :

Roman

period :

Meroitic prince smiting his enemies (early first century AD) Strabo describes a war with the Romans in the first century BC. According to Strabo, the Kushites "sacked Aswan with an army of 30,000 men and destroyed imperial statues...at Philae." a "fine over-life-size bronze head of the emperor Augustus" was found buried in Meroe in front of a temple. After the initial victories of Kandake (or "Candace") Amanirenas against Roman Egypt, the Kushites were defeated and Napata sacked. Remarkably, the destruction of the capital of Napata was not a crippling blow to the Kushites and did not frighten Candace enough to prevent her from again engaging in combat with the Roman military. In 22 BC, a large Kushite force moved northward with intention of attacking Qasr Ibrim.

Alerted to the advance, Petronius again marched south and managed to reach Qasr Ibrim and bolster its defenses before the invading Kushites arrived. Welsby states after a Kushite attack on Primis (Qasr Ibrim), the Kushites sent ambassadors to negotiate a peace settlement with Petronius. The Kushites succeeded in negotiating a peace treaty on favorable terms. Trade between the two nations increased and the Roman Egyptian border being extended to "Hiera Sykaminos (Maharraqa)." This arrangement "guaranteed peace for most of the next 300 years" and there's "no definite evidence of further clashes."

It is possible that the Roman emperor Nero planned another attempt to conquer Kush before his death in AD 68. Nero sent two centurions upriver as far as Bahr el Ghazal River in 66 AD in an attempt to discover the source of the Nile, per Senecas, or plan an attack, per Pliny. Kush began to fade as a power by the 1st or 2nd century AD, sapped by the war with the Roman province of Egypt and the decline of its traditional industries. However, there is evidence of 3rd century AD Kushite Kings at Philae in demotic and inscription. It's been suggested that the Kushites reoccupied lower Nubia after Roman forces were withdrawn to Aswan. Kushite activities led others to note "a de facto Kushite control of that area (as far north as Philae) for part of the 3rd century AD. Thereafter, it weakened and disintegrated due to internal rebellion [citation needed]. The seat was eventually captured and burnt to the ground by the Kingdom of Aksum. [citation needed] Christianity began to gain over the old pharaonic religion and by the mid-sixth century AD the Kingdom of Kush was dissolved.

Language and writing :

Meroitic ostracon The Meroitic language was spoken in Meroë and Sudan during the Meroitic period (attested from 300 BC). It became extinct about 400 AD. It is uncertain to which language family the Meroitic language is related. Kirsty Rowan suggests that Meroitic, like the Egyptian language, belongs to the Afro-Asiatic family. She bases this on its sound inventory and phonotactics, which she argues are similar to those of the Afro-Asiatic languages and dissimilar from those of the Nilo-Saharan languages. Claude Rilly proposes that Meroitic, like the Nobiin language, belongs to the Eastern Sudanic branch of the Nilo-Saharan family, based in part on its syntax, morphology, and known vocabulary.

In the Napatan Period Egyptian hieroglyphs were used: at this time writing seems to have been restricted to the court and temples. From the 2nd century BC, there was a separate Meroitic writing system. The language was written in two forms of the Meroitic alphabet: Meroitic Cursive, which was written with a stylus and was used for general record-keeping; and Meroitic Hieroglyphic, which was carved in stone or used for royal or religious documents. It is not well understood due to the scarcity of bilingual texts. The earliest inscription in Meroitic writing dates from between 180–170 BC. These hieroglyphics were found engraved on the temple of Queen Shanakdakhete. Meroitic Cursive is written horizontally, and reads from right to left like all Semitic orthographies. This was an alphabetic script with 23 signs used in a hieroglyphic form (mainly on monumental art) and in a cursive form. The latter was widely used; so far some 1278 texts using this version are known (Leclant 2000). The script was deciphered by Griffith, but the language behind it is still a problem, with only a few words understood by modern scholars. It is not as yet possible to connect the Meroitic language with other known languages. For a time, it was also possibly used to write the Old Nubian language of the successor Nubian kingdoms.

Technology,

medicine, and mathematics :

The "Great Hafir" at Musawwarat es-Sufra. This artificial reservoir was built to retain the rainfall of the short, wet season. It is 250 m in diameter and 6.3 m deep The Kushites invented reservoirs in the form of the Hafir, during the Meroitic period. 800 ancient and modern hafirs have been registered in the Meroitic town of Butana. The functions of Hafirs were to catch water during the rainy season for storage, to ensure water is available for several months during the dry season as well as supply drinking water, irrigate fields, and water cattle. The Great Reservoir near the Lion Temple in Musawwarat es-Sufra is a notable hafir built by the Kushites.

Bloomeries and blast furnaces could have been used in metalworking at Meroë. Early records of bloomery furnaces dated at least to 7th and 6th century BC have been discovered in Kush. It is known that the ancient bloomeries that produced metal tools for the Kushites produced a surplus for sale.

Medicine

:

Mathematics

:

Military

:

Bowmen were the most important force components in the Kushite military. Ancient sources indicate that Kushite archers favored one-piece bows that were between six to seven feet long, with so powerful a draw strength that many of the archers used their feet to bend their bows. However, composite bows were also used in their arsenal. Greek historian, Herodotus indicated that primary bow construction was of seasoned palm wood, with arrows made of cane. Kushite arrows were often poisoned-tipped. Elephants were occasionally used in warfare during the Meroitic period as seen in the war against Rome around 20 BC.

Architecture :

During the Bronze age, Nubian ancestors of the Kingdom of Kush built speoi (a speos is a temple or tomb cut into a rock face) between 3700 to 3250 BCE. This greatly influenced the architecture of the New kingdom. Tomb monuments were one of the more recognizable expressions of Kushite architecture. Uniquely Kushite tomb monuments were found from the beginning of the empire, at el Kurru, to the decline of the Kingdom. These monuments developed organically from Middle Nile (e.g. A-group) burial types. Tombs became progressively larger during the 25th dynasty, culminating in Taharqa's underground rectangular building with "aisles of square piers...the whole being cut from the living rock." Kushites also created pyramids, mud-brick temples (deffufa), and masonry temples. Kushites borrowed much from Egypt, as it relates to temple design. Kushite temples were quite diverse in their plans, except for the Amun temples which all have the same basic plan.

The Jebel Barkal and Meroe Amun temples are exceptions with the 150m long Jebel Barkal being "by far the largest 'Egyptian' temple ever built in Nubia." Temples for major Egyptian deities were built on "a system of internal harmonic proportions" based on "one or more rectangles each with sides in the ratio of 8:5". Kush also invented Nubian vaults.

Piye is thought to have constructed the first true pyramid at el Kurru. Pyramids are "the archetypal tomb monument of the Kushite royal family" and found at "el Kurru, Nuri, Jebel Barkal, and Meroe." The Kushite pyramids are smaller with steeper sides than northern Egyptian pyramids. The Kushites are thought to have copied the pyramids of New Kingdom elites, as opposed to Old and Middle Kingdom pharaohs. Kushite housing consisted mostly of circular timber huts with some apartment houses with several two-room apartments. The apartment houses likely accommodated extended families.

The Kushites built a stone-paved road at Jebel Barkal, are thought to have built piers/harbors on the Nile river, and many wells.

Kush

and Egyptology :

Kushite images :

Portrait of Taharqa, Kerma Museum

The "Archer King", an unknown king of Meroe, 3rd century BCE. National Museum of Sudan

Copy of relief from Naqa depicting Amanitore (second from left), Natakamani (second from right) and two princes approaching a three-headed Apedemak

Taharqa's shrine, Ashmolean museum in Oxford, UK

Taharqa's kiosk, Karnak Temple

Pharaoh Taharqa of Ancient Egypt's 25th Dynasty. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford UK Part I Source :

https://www.ancient.eu/

Part II Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

.jpg)

.jpg)

._Museum_of_Fine_Arts,_Boston.jpg)

.jpg)

_,_Kerma_Museum,Sudan_(2).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)