| BACTRIA Bactria :

Province of the Achaemenid Empire, Seleucid Empire, Greco-Bactrian Kingdom and Indo-Greek Kingdom, 2500 / 2000 BC – 900 / 1000 AD.

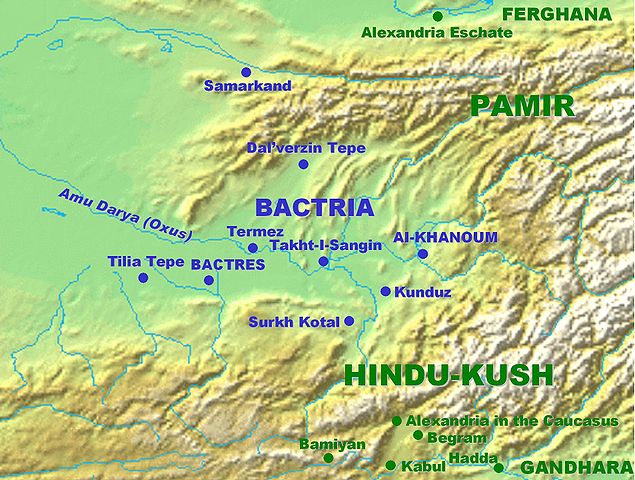

Approximate location of the region of Bactria

Ancient cities of Bactria Capital

: Bactra

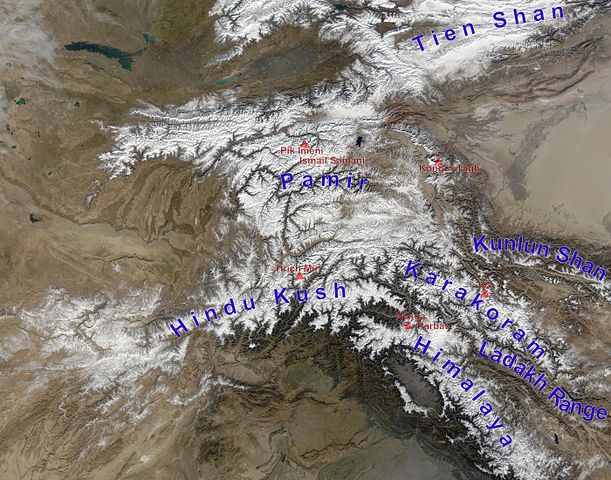

Bactria (Bactrian: Bakhlo), or Bactriana, was an ancient region in Central Asia. Bactria proper was north of the Hindu Kush mountain range and south of the Amu Darya river, covering the flat region that straddles modern-day Afghanistan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. More broadly Bactria was the area north of the Hindu Kush, west of the Pamirs and south of the Tian Shan, with the Amu Darya flowing west through the centre.

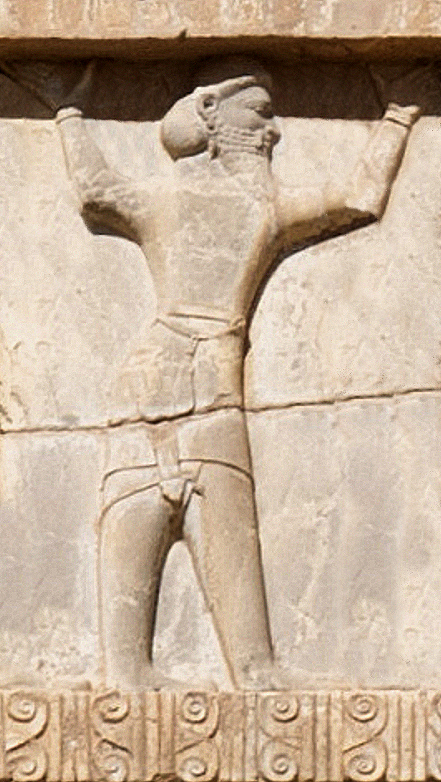

Called "beautiful Bactria, crowned with flags" by the Avesta, the region is one of the sixteen perfect Iranian lands that the supreme deity Ahura Mazda had created. One of the early centres of Zoroastrianism and capital of the legendary Kayanian kings of Iran, Bactria is mentioned in the Behistun Inscription of Darius the Great as one of the satrapies of the Achaemenid Empire; it was a special satrapy and was ruled by a crown prince or an intended heir. Bactria was centre of Iranian resistance against the Macedonian invaders after fall of the Achaemenid Empire in the 4th century BC, but eventually fell to Alexander the Great. After death of the Macedonian conqueror, Bactria was annexed by his general, Seleucus I.

Nevertheless, the Seleucids lost the region after declaration of independence by the satrap of Bactria, Diodotus I; thus started history of the Greco-Bactrian and the later Indo-Greek Kingdoms. By the 2nd century BC, Bactria was conquered by the Iranian Parthian Empire, and in the early 1st century, the Kushan Empire was formed by the Yuezhi in the Bactrian territories. Shapur I, the second Sasanian King of Kings of Iran, conquered western parts of the Kushan Empire in the 3rd century, and the Kushano-Sasanian Kingdom was formed. The Sasanians lost Bactria in the 4th century, however, it was reconquered in the 6th century. With the Muslim conquest of Iran in the 7th century, Islamization of Bactria began.

Bactria was centre of an Iranian Renaissance in the 8th and 9th centuries, and New Persian as an independent literary language first emerged in this region. The Samanid Empire was formed in Eastern Iran by the descendants of Saman Khuda, a Persian from Bactria; thus started spread of Persian language in the region and decline of Bactrian language.

Bactrian, an Eastern Iranian language, was the common language of Bactria and surroundings areas in ancient and early medieval times. Zoroastrianism and Buddhism were the religions of the majority of Bactrians before the rise of Islam.

Name :

Bactria between the Hindu Kush (south), Pamirs (east), south branch of Tianshan (north) Ferghana Valley to the north; western Tarim Basin to the east The English name Bactria is derived from the Ancient Greek (Romanized: Baktriani), a Hellenized version of the Bactrian endonym (Romanized: Bakhlo). Analogous names include Avestan Bakhdi, Old Persian Baxtriš, Middle Persian Baxl, New Persian (Romanized: Balx), Chinese (pinyin: Dàxià), Latin Bactriana and Sanskrit: (Romanized: Bahlika).

Geography

:

Bactria, the territory of which Bactra [Balkh] was the capital, originally consisted of the area south of the Amu Darya with its string of agricultural oases dependent on water taken from the rivers of Balk (Bactra) [Balkh], Tashkurgan, Konduz [Kunduz], Sar-e Pol, and Širin Tagao [Shirin Tagab]. This region played a major role in Central Asian history. At certain times the political limits of Bactria stretched far beyond the geographic frame of the Bactrian plain.

History

:

Goddesses, Bactria, Afghanistan, 2000 – 1800 BC

Ancient bowl with animals, Bactria, 3rd – 2nd millennium BC The Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC, also known as the "Oxus civilization") is the modern archaeological designation for a Bronze Age archaeological culture of Central Asia, dated to c. 2200–1700 BC, located in present-day eastern Turkmenistan, northern Afghanistan, southern Uzbekistan and western Tajikistan, centred on the upper Amu Darya (known to the ancient Greeks as the Oxus River), an area covering ancient Bactria. Its sites were discovered and named by the Soviet archaeologist Viktor Sarianidi (1976). Bactria was the Greek name for Old Persian Baxtriš (from native *Baxçiš) (named for its capital Bactra, modern Balkh), in what is now northern Afghanistan, and Margiana was the Greek name for the Persian satrapy of Margu, the capital of which was Merv, in today's Turkmenistan.

The early Greek historian Ctesias, c. 400 BC (followed by Diodorus Siculus), alleged that the legendary Assyrian king Ninus had defeated a Bactrian king named Oxyartes in c. 2140 BC, or some 1000 years before the Trojan War. Since the decipherment of cuneiform script in the 19th century, however, which enabled actual Assyrian records to be read, historians have ascribed little value to the Greek account.

According to some writers, [who?] Bactria was the homeland (Airyanem Vaejah) of Indo-Iranians who moved south-west into Iran and the north-west of the Indian subcontinent around 2500–2000 BC. Later, it became the northern province of the Achaemenid Empire in Central Asia. It was in these regions, where the fertile soil of the mountainous country is surrounded by the Turan Depression, that the prophet Zoroaster was said to have been born and gained his first adherents. Avestan, the language of the oldest portions of the Zoroastrian Avesta, was one of the Old Iranian languages, and is the oldest attested member of the Eastern Iranian languages.

Achaemenid Empire :

Ernst Herzfeld suggested that before its annexation to the Achaemenid Empire by Cyrus the Great in sixth century BC, Bactria belonged to the Medes and together with Margiana, formed the twelfth satrapy of Persia. After Darius III had been defeated by Alexander the Great, the satrap of Bactria, Bessus, attempted to organise a national resistance but was captured by other warlords and delivered to Alexander. He was then tortured and killed.

Under Persian rule, many Greeks were deported to Bactria, so that their communities and language became common in the area. During the reign of Darius I, the inhabitants of the Greek city of Barca, in Cyrenaica, were deported to Bactria for refusing to surrender assassins. In addition, Xerxes also settled the "Branchidae" in Bactria; they were the descendants of Greek priests who had once lived near Didyma (western Asia Minor) and betrayed the temple to him. Herodotus also records a Persian commander threatening to enslave daughters of the revolting Ionians and send them to Bactria. However, these few examples are not indicative of massive deportations of Greeks to central Asia.

Alexander :

Pre-Seleucid Athenian owl imitation from Bactria, possibly from the time of Sophytes Alexander conquered Sogdiana. In the south, beyond the Oxus, he met strong resistance. After two years of war and a strong insurgency campaign, Alexander managed to establish little control over Bactria. After Alexander's death, Diodorus Siculus tells us that Philip received dominion over Bactria, but Justin names Amyntas to that role. At the Treaty of Triparadisus, both Diodorus Siculus and Arrian agree that the satrap Stasanor gained control over Bactria. Eventually, Alexander's empire was divided up among the generals in Alexander's army. Bactria became a part of the Seleucid Empire, named after its founder, Seleucus I.

Seleucid

Empire :

The paradox that Greek presence was more prominent in Bactria than in areas far closer to Greece can possibly be explained [original research?] by past deportations of Greeks to Bactria.

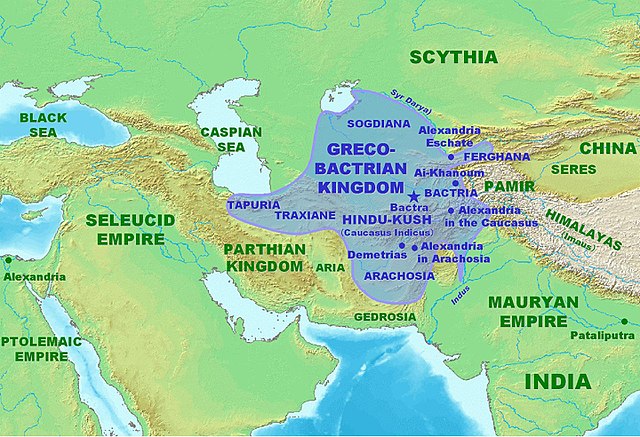

Greco-Bactrian Kingdom :

Map of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom at its maximum extent, circa 180 BC Considerable difficulties faced by the Seleucid kings and the attacks of Pharaoh Ptolemy II Philadelphus gave the satrap of Bactria, Diodotus I, the opportunity to declare independence about 245 BC and conquer Sogdia. He was the founder of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom. Diodotus and his successors were able to maintain themselves against the attacks of the Seleucids—particularly from Antiochus III the Great, who was ultimately defeated by the Romans (190 BC).

The Greco-Bactrians were so powerful that they were able to expand their territory as far as India :

As for Bactria, a part of it lies alongside Aria towards the north, though most of it lies above Aria and to the east of it. And much of it produces everything except oil. The Greeks who caused Bactria to revolt grew so powerful on account of the fertility of the country that they became masters, not only of Bactria and beyond, but also of India, as Apollodorus of Artemita says: and more tribes were subdued by them than by Alexander...."

The Greco-Bactrians used the Greek language for administrative purposes, and the local Bactrian language was also Hellenized, as suggested by its adoption of the Greek alphabet and Greek loanwords. In turn, some of these words were also borrowed by modern Pashto.

Indo-Greek Kingdom :

The Bactrian king Euthydemus I and his son Demetrius I crossed the Hindu Kush mountains and began the conquest of the Indus valley. For a short time, they wielded great power: a great Greek empire seemed to have arisen far in the East. But this empire was torn by internal dissension and continual usurpations. When Demetrius advanced far east of the Indus River, one of his generals, Eucratides, made himself king of Bactria, and soon in every province there arose new usurpers, who proclaimed themselves kings and fought against each other.

Most of them we know only by their coins, a great many of which are found in Afghanistan. By these wars, the dominant position of the Greeks was undermined even more quickly than would otherwise have been the case. After Demetrius and Eucratides, the kings abandoned the Attic standard of coinage and introduced a native standard, no doubt to gain support from outside the Greek minority. In the Indus valley, this went even further. The Indo-Greek king Menander I (known as Milind in India), recognized as a great conqueror, converted to Buddhism. His successors managed to cling to power until the last known Indo-Greek ruler, a king named Strato II, who ruled in the Punjab region until around 55 BC. Other sources, however, place the end of Strato II's reign as late as 10 AD.

Daxia,

Tukhara and Tokharistan :

During the 2nd century BC, the Greco-Bactrians were conquered by nomadic Indo-European tribes from the north, beginning with the Sakas (160 BC). The Sakas were overthrown in turn by the Da Yuezhi ("Greater Yuezhi") during subsequent decades. The Yuezhi had conquered Bactria by the time of the visit of the Chinese envoy Zhang Qian (circa 127 BC), who had been sent by the Han emperor to investigate lands to the west of China. The first mention of these events in European literature appeared in the 1st century BC, when Strabo described how "the Asii, Pasiani, Tokhari, and Sakarauli" had taken part in the "destruction of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom". Ptolemy subsequently mentioned the central role of the Tokhari among other tribes in Bactria. As Tukhar or Tokhar it included areas that were later part of Surxondaryo Province in Uzbekistan, southern Tajikistan and northern Afghanistan. The Tokhari spoke a language known later as Bactrian – an Iranian language. (The Tokhari and their language should not be confused with the Tocharian people who lived in the Tarim Basin between the 3rd and 9th centuries AD, or the Tocharian languages that form another branch of Indo-European languages.)

The treasure of the royal burial Tillia tepe is attributed to 1st century BC Sakas in Bactria

Zhang Qian taking leave from emperor Han Wudi, for his expedition to Central Asia from 138 to 126 BC, Mogao Caves mural, 618 – 712 AD

The name Daxia was used in the Shiji ("Records of the Grand

Historian") by Sima Qian. Based on the reports of Zhang Qian,

the Shiji describe Daxia as an important urban civilization of about

one million people, living in walled cities under small city kings

or magistrates. Daxia was an affluent country with rich markets,

trading in an incredible variety of objects, coming from as far

as Southern China. By the time Zhang Qian visited, there was no

longer a major king, and the Bactrians were under the suzerainty

of the Yuezhi. Zhang Qian depicted a rather sophisticated but demoralised

people who were afraid of war. Following these reports, the Chinese

emperor Wu Di was informed of the level of sophistication of the

urban civilizations of Ferghana, Bactria and Parthia, and became

interested in developing commercial relationship with them :

These contacts immediately led to the dispatch of multiple embassies from the Chinese, which helped to develop trade along the Silk Roads.

Kushan worshipper with Zeus / Serapis / Ohrmazd, Bactria, 3rd century AD

Kushan worshipper with Pharro, Bactria, 3rd century AD Kujula Kadphises, the xihou (prince) of the Yuezhi, united the region in the early 1st century and laid the foundations for the powerful, but short-lived, Kushan Empire.

In the 3rd century AD, Tukhar was under the rule of the Kushanshas (Indo-Sasanians).

The form Tokharistan – the suffix -stan means "place of" in Persian – appeared for the first time in the 4th century, in Buddhist texts, such as the Vibhas-shastra. Tokhar was known in Chinese sources as Tuhuluo which is first mentioned during the Northern Wei era. In the Tang dynasty, the name is transcribed as Tuhuoluo. Other Chinese names are Doushaluo, Douquluo or Duhuoluo. [citation needed] During the 5th century, Bactria was controlled by the Xionites and the Hephthalites, but was subsequently reconquered by the Sassanid Empire.

Introduction

of Islam :

In 663, the Umayyad Caliphate attacked the Buddhist Shahi dynasty ruling in Tokharistan. The Umayyad forces captured the area around Balkh, including the Buddhist monastery at Nava Vihara, causing the Shahis to retreat to the Kabul Valley.

In the 8th century, a Persian from Balkh known as Saman Khuda left Zoroastrianism for Islam while living under the Umayyads. His children founded the Samanid Empire (875–999). Persian became the official language and had a higher status than Bactrian, because it was the language of Muslim rulers. It eventually replaced the latter as the common language due to the preferential treatment as well as colonization.

Bactrian people :

Painted clay and alabaster head of a mobad wearing a distinctive Bactrian-style headdress, Takhti-Sangin, Tajikistan, Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, third–second century BC Bactrians were the inhabitants of Bactria. Several important trade routes from India and China (including the Silk Road) passed through Bactria and, as early as the Bronze Age, this had allowed the accumulation of vast amounts of wealth by the mostly nomadic population. The first proto-urban civilization in the area arose during the 2nd millennium BC.

Control of these lucrative trade routes, however, attracted foreign interest, and in the 6th century BC the Bactrians were conquered by the Persians, and in the 4th century BC by Alexander the Great. These conquests marked the end of Bactrian independence. From around 304 BC the area formed part of the Seleucid Empire, and from around 250 BC it was the centre of a Greco-Bactrian kingdom, ruled by the descendants of Greeks who had settled there following the conquest of Alexander the Great.

The Greco-Bactrians, also known in Sanskrit as Yavans, worked in cooperation with the native Bactrian aristocracy. By the early 2nd century BC the Greco-Bactrians had created an impressive empire that stretched southwards to include north-west India. By about 135 BC, however, this kingdom had been overrun by invading Yuezhi tribes, an invasion that later brought about the rise of the powerful Kushan Empire.

Bactrians were recorded in Strabo's Geography'

"Now in early times the Sogdians and Bactrians did not differ much from the nomads in their modes of life and customs, although the Bactrians were a little more civilised; however, of these, as of the others, Onesicritus does not report their best traits, saying, for instance, that those who have become helpless because of old age or sickness are thrown out alive as prey to dogs kept expressly for this purpose, which in their native tongue are called "undertakers," and that while the land outside the walls of the metropolis of the Bactrians looks clean, yet most of the land inside the walls is full of human bones; but that Alexander broke up the custom."

The

Bactrians spoke Bactrian, a north-eastern Iranian language. Bactrian

became extinct, replaced by north-eastern Iranian languages such

as Pashto, Yidgha, Munji, and Ishkashmi. The Encyclopaedia Iranica

states:

The

principal religions of the area before Islam were Zoroastrianism

and Buddhism. Contemporary Tajiks are the descendants of ancient

Eastern Iranian inhabitants of Central Asia, in particular, the

Sogdians and the Bactrians, and possibly other groups, with an admixture

of Western Iranian Persians and non-Iranian peoples. The Encyclopædia

Britannica states:

In

popular culture :

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |