EURASIAN

STEPPE

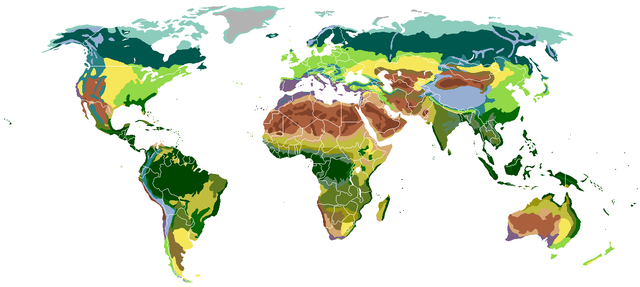

Eurasian

steppe belt (turquoise)

The

Eurasian Steppe, also called the Great Steppe or the steppes, is

the vast steppe ecoregion of Eurasia in the temperate grasslands,

savannas, and shrublands biome. It stretches from Bulgaria, Romania,

Moldova, Ukraine, Western Russia, Siberia, Kazakhstan, Xinjiang,

Mongolia, and Manchuria, with one major exclave, the Pannonian steppe

or Puszta, located mostly in Hungary.

Since

the Paleolithic age, the Steppe Route has connected Central Europe,

Eastern Europe, Western Asia, Central Asia, Eastern Asia, and Southern

Asia economically, politically, and culturally through overland

trade routes. The Steppe route is a predecessor not only of the

Silk Road which developed during antiquity and the Middle Ages,

but also of the Eurasian Land Bridge in the modern era. It has been

home to nomadic empires and many large tribal confederations and

ancient states throughout history, such as the Xiongnu, Scythia,

Cimmeria, Sarmatia, Hunnic Empire, Chorasmia, Transoxiana, Sogdiana,

Xianbei, Mongols, and Göktürk Khaganate.

Geography

:

_no_borders.png)

The

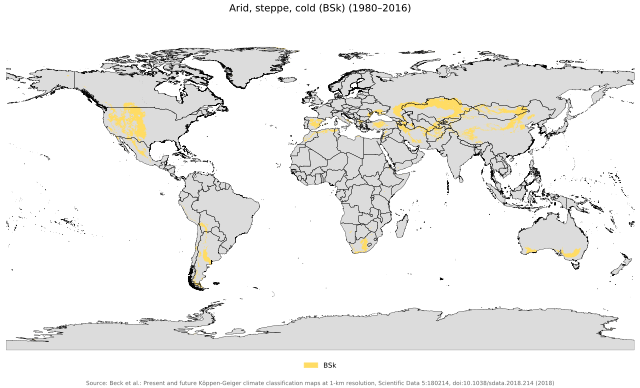

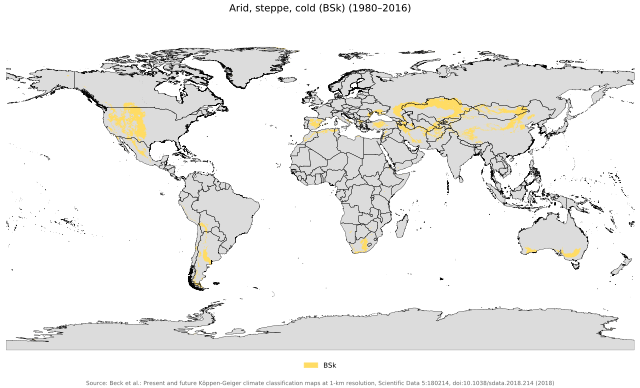

Köppen climate classification

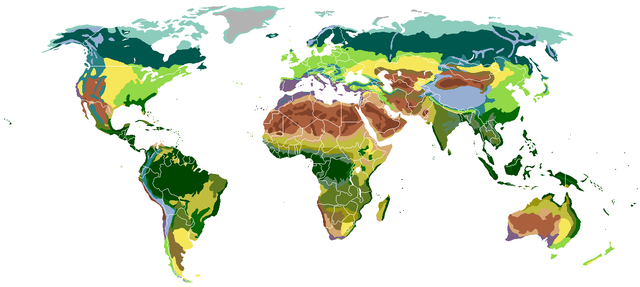

Biomes

classified by vegetation

.svg.png)

Humid

continental climate worldwide, utilizing the Köppen climate

classification

Cold

steppe climate worldwide, utilizing the Köppen climate classification

Divisions :

The Eurasian Steppe extends thousands of miles from near the mouth

of the Danube almost to the Pacific Ocean. It is bounded on the

north by the forests of European Russia, Siberia and Asian Russia.

There is no clear southern boundary although the land becomes increasingly

dry as one moves south. The steppe narrows at two points, dividing

it into three major parts.

Pannonian

steppe (Exclave) :

The Pannonian steppe is an exclave of the Eurasian Steppe belt.

It is found in modern-day Austria, Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania, Serbia

and Slovakia.

Devínska Kobyla, Bratislava, Slovakia

The

Pannonian steppe in Seewinkel, Austria

The

Pannonian steppe in Devínska Kobyla, Bratislava, Slovakia

Danube-Auen

National Park, Austria

Pontic–Caspian

steppe (Western Steppe) :

The Pontic–Caspian steppe begins near the mouth of the Danube

and extends northeast almost to Kazan and then southeast to the

southern tip of the Ural Mountains. Its northern edge was a broad

band of forest steppe which has now been obliterated by the conversion

of the whole area to agricultural land. In the southeast the Black

Sea–Caspian Steppe extends between the Black Sea and Caspian

Sea to the Caucasus Mountains. In the west, the Great Hungarian

Plain is an island of steppe separated from the main steppe by the

mountains of Transylvania. On the north shore of the Black Sea,

the Crimean Peninsula has some interior steppe and ports on the

south coast which link the steppe to the civilizations of the Mediterranean

basin.

The Pontic–Caspian steppe near Krynychne, Ukraine

The

Pontic–Caspian steppe in Henichesk, Ukraine

Steppes

in Gagauzia, Moldova

Steppes

in Gagauzia, Dezghingea, Moldova

Ural–Caspian

Narrowing :

The Ural Mountains extend south to a point about 650 km (400 mi)

northeast of the Caspian Sea.

Wooded Ural Mountains of Beloretsky District, Russia

The

Bashkiriya National Park is situated in the southern end of the

Ural Mountains, Russia

The

Bashkiriya National Park, Ural Mountains, Russia

The

Bashkiriya National Park, Ural Mountains, Russia

Kazakh

Steppe (Central Steppe) :

The Kazakh Steppe extends from the Urals to Dzungaria. To the south,

it grades off into semi-desert and desert which is interrupted by

two great rivers, the Amu Darya (Oxus) and Syr Darya (Jaxartes),

which flow northwest into the Aral Sea and provide irrigation agriculture.

In the southeast is the densely populated Fergana Valley and west

of it the great oasis cities of Tashkent, Samarkand and Bukhara

along the Zeravshan River. The southern area has a complex history,

while in the north, the Kazakh Steppe proper was relatively isolated

from the main currents of written history.

The steppe in Akmola Region, Kazakhstan

The

steppes in Akmola Province, Kazakhstan

The

Kazakh Steppe in the Ayagoz District, Kazakhstan

The

Kazakh Steppe in the early spring

Dzungarian

Narrowing :

On the east side of the former Sino-Soviet border mountains extend

north almost to the forest zone with only limited grassland in Dzungaria.

The

east-west Tien Shan Mountains divide it into Dzungaria in the north

and the Tarim Basin to the south. Dzungaria is bounded by the Tarbagatai

Mountains on the west and the Mongolian Altai Mountains on the east,

neither of which is a significant barrier. Dzungaria has good grassland

around the edges and a central desert. It often behaved as a westward

extension of Mongolia and connected Mongolia to the Kazakh steppe.

To the north of Dzungaria are mountains and the Siberian forest.

To the south and west of Dzungaria, and separated from it by the

Tian Shan mountains, is an area about twice the size of Dzungaria,

the oval Tarim Basin. The Tarim Basin is too dry to support even

a nomadic population, but around its edges rivers flow down from

the mountains giving rise to a ring of cities which lived by irrigation

agriculture and east-west trade. The Tarim Basin formed an island

of near civilization in the center of the steppe. The Northern Silk

Road went along the north and south sides of the Tarim Basin and

then crossed the mountains west to the Fergana Valley. At the west

end of the basin the Pamir Mountains connect the Tien Shan Mountains

to the Himalayas. To the south, the Kunlun Mountains separate the

Tarim Basin from the thinly peopled Tibetan Plateau.

Uvs Lake Basin, Tuva Republic, Russia

Dus-Khol

lake, Tuva Republic, Russia

The

grassland in Tuva Republic, Russia

Dus-Khol

Lake, Tandinsky District, Tuva Republic, Russia

Mongolian-Manchurian

steppe (Eastern Steppe) :

The Mongol Steppe includes both Mongolia and the Chinese province

of Inner Mongolia. The two are separated by a relatively dry area

marked by the Gobi Desert. South of the Mongol Steppe is the high

and thinly peopled Tibetan Plateau. The northern edge of the plateau

is the Gansu or Hexi Corridor, a belt of moderately dense population

that connects China proper with the Tarim Basin. The Hexi Corridor

was the main route of the Silk Road. In the southeast the Silk Road

led over some hills to the east-flowing Wei River valley which led

to the North China Plain.

Manchuria

is a special case. Westerners tend to think of Manchuria as the

northeast projection of China that they see on maps. The Chinese

now call this the eastern two thirds of Northeast China. The dryer

western third west of the Greater Khingan Mountains has normally

been part of Inner Mongolia. Before 1859, Manchuria also included

Outer Manchuria to the north and east, which is now part of Russia.

South of the Khingan Mountains and north of the Taihang Mountains,

the Mongolian-Manchurian steppe extends east into Manchuria as the

Liao Xi steppe. In Manchuria, the steppe grades off into forest

and mountains without reaching the Pacific. The central area of

forest-steppe was inhabited by pastoral and agricultural peoples,

while to the north and east was a thin population of hunting tribes

of the Siberian type.

The Daurian forest steppe

The

Mongolian-Manchurian grassland in the Khövsgöl Province,

Mongolia

Grass

steppe in the Khövsgöl Province, Mongolia

Daursky

Nature Reserve in the southern part of the Zabaykalsky Krai in Siberia,

Russia, close to the border with Mongolia

The

Mongolian-Manchurian grassland in Inner Mongolia, China

Fauna

:

Big mammals of the Eurasian steppe were the Przewalski's horse,

the saiga antelope, the Mongolian gazelle, the goitered gazelle,

the wild Bactrian camel and the onager. The gray wolf and the corsac

fox and occasionally the brown bear are predators roaming the steppe.

Smaller mammal species are the Mongolian gerbil, the little souslik

and the bobak marmot.

Furthermore,

the Eurasian steppe is home to a great variety of bird species.

Threatened bird species living there are for example the imperial

eagle, the lesser kestrel, the great bustard, the pale-back pigeon

and the white-throated bushchat.

Przewalski horse

Corsac

fox

Saiga

antelope

Onager

The

primary domesticated animals raised were sheep and goats with fewer

cattle than one might expect. Camels were used in the drier areas

for transport as far west as Astrakhan. There were some yaks along

the edge of Tibet. The horse was used for transportation and warfare.

The horse was first domesticated on the Pontic–Caspian or

Kazakh steppe sometime before 3000 BC, but it took a long time for

mounted archery to develop and the process is not fully understood.

The stirrup does not seem to have been completely developed until

300 AD (see Stirrup, Saddle, Composite bow, Domestication of the

horse and related articles).

Ecoregions

:

The World Wide Fund for Nature divides the Eurasian steppe's temperate

grasslands, savannas, and shrublands into a number of ecoregions,

distinguished by elevation, climate, rainfall, and other characteristics,

and home to distinct animal and plant communities and species, and

distinct habitat ecosystems.

•

Alai–Western Tian Shan steppe (Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan)

• Altai steppe and semi-desert (Kazakhstan)

• Baraba steppe (Russia)

• Daurian forest steppe (China, Mongolia, Russia)

• Emin Valley steppe (China, Kazakhstan)

• Kazakh forest steppe (Kazakhstan, Russia)

• Kazakh Steppe (Kazakhstan, Russia)

• Kazakh Uplands (Kazakhstan)

• Mongolian-Manchurian grassland (China, Mongolia,

Russia)

• Pontic–Caspian steppe (Moldova, Romania,

Russia, Ukraine)

• Sayan Intermontane steppe (Russia)

• Selenge–Orkhon forest steppe (Mongolia, Russia)

• South Siberian forest steppe (Russia)

• Tian Shan foothill arid steppe (China, Kazakhstan,

Kyrgyzstan)

• Pannonian Steppe (Hungary, Romania, Serbia, Croatia,

Slovakia, Austria, Slovenia)

Human activities :

The site of Por-Bazhyn

Mongolian

yurt

Trade habits :

The major centers of population and high culture in Eurasia are

Europe, the Middle East, India and China. For some purposes it is

useful to treat Greater Iran as a separate region. All these regions

are connected by the Eurasian Steppe route which was an active predecessor

of the Silk Road. The latter started in the Guanzhong region of

China and ran west along the Hexi Corridor to the Tarim Basin. From

there it went southwest to Greater Iran and turned southeast to

India or west to the Middle East and Europe. A minor branch went

northwest along the great rivers and north of the Caspian Sea to

the Black Sea. When faced with a rich caravan the steppe nomads

could either rob it, or tax it, or hire themselves out as guards.

Economically these three forms of taxation or parasitism amounted

to the same thing. Trade was usually most vigorous when a strong

empire controlled the steppe and reduced the number of petty chieftains

preying on trade. The silk road first became significant and Chinese

silk began reaching the Roman Empire about the time that the Emperor

of Han pushed Chinese power west to the Tarim Basin.

Agriculture

:

Plowing

with tractor on the Great Hungarian Plain (Alföld), Hungary

Steppe

fire in the Kostanay Region, Kazakhstan

The nomads would occasionally tolerate colonies of peasants on the

steppe in the few areas where farming was possible. These were often

captives who grew grain for their nomadic masters. Along the fringes

there were areas that could be used for either plowland or grassland.

These alternated between one and the other depending on the relative

strength of the nomadic and agrarian heartlands. Over the last few

hundred years, the Russian steppe and much of Inner Mongolia has

been cultivated. The fact that most of the Russian steppe is not

irrigated implies that it was maintained as grasslands as a result

of the military strength of the nomads.

Language

:

According to the most widely held hypothesis of the origin of the

Indo-European languages, the Kurgan hypothesis, their common ancestor

is thought to have originated on the Pontic-Caspian steppe. The

Tocharians were an early Indo-European branch in the Tarim Basin.

At the beginning of written history the entire steppe population

west of Dzungaria spoke Iranian languages. From about 500 AD the

Turkic languages replaced the Iranian languages first on the steppe,

and later in the oases north of Iran. Additionally, Hungarian speakers,

a branch of the Uralic language family, who previously lived in

the steppe in what is now Southern Russia, settled in the Carpathian

basin in year 895. Mongolic languages are in Mongolia. In Manchuria

one finds Tungusic languages and some others.

Religion

:

Tengriism was introduced by Turko-Mongol nomads. Nestorianism and

Manichaeism spread to the Tarim Basin and into China, but they never

became established majority religions. Buddhism spread from the

north of India to the Tarim Basin and found a new home in China.

By about 1400 AD, the entire steppe west of Dzungaria had adopted

Islam. [citation needed] By about 1600 AD, Islam was established

in the Tarim Basin while Dzungaria and Mongolia had adopted Tibetan

Buddhism.

History

:

Warfare :

Raids between tribes were prevalent throughout the region's history.

This is connected to the ease with which a defeated enemy's flocks

can be driven away, making raiding profitable. In terms of warfare

and raiding, in relation to sedentary societies, the horse gave

the nomads an advantage of mobility. Horsemen could raid a village

and retreat with their loot before an infantry-based army could

be mustered and deployed. When confronted with superior infantry,

horsemen could simply ride away and retreat and regroup. Outside

of Europe and parts of the Middle East, agrarian societies had difficulty

raising a sufficient number of war horses, and often had to enlist

them from their nomadic enemies (as mercenaries). Nomads could not

easily be pursued onto the steppe since the steppe could not easily

support a land army. If the Chinese sent an army into Mongolia,

the nomads would flee and come back when the Chinese ran out of

supplies. But the steppe nomads were relatively few and their rulers

had difficulty holding together enough clans and tribes to field

a large army. If they conquered an agricultural area they often

lacked the skills to administer it. If they tried to hold agrarian

land they gradually absorbed the civilization of their subjects,

lost their nomadic skills and were either assimilated or driven

out.

Relations

with neighbors :

Hungarian

invasions of Europe in the 9–10th century

Territories

of the Golden Horde under Öz Beg Khan

Along the northern fringe the nomads would collect tribute from

and blend with the forest tribes. [citation needed] From about 1240

to 1480 Russia paid tribute to the Golden Horde. [citation needed]

South of the Kazakh steppe the nomads blended with the sedentary

population, partly because the Middle East has significant areas

of steppe (taken by force in past invasions) and pastoralism. There

was a sharp cultural divide between Mongolia and China and almost

constant warfare from the dawn of history until the Qing conquest

of Dzungaria in 1757. [citation needed] The nomads collected large

amounts of tribute from the Chinese and several Chinese dynasties

were of steppe origin. Perhaps because of the mixture of agriculture

and pastoralism in Manchuria its inhabitants, the Manchu, knew how

to deal with both nomads and the settled populations, and therefore

were able to conquer much of northern China when both Chinese and

Mongols were weak.

Legacy

of the Eurasian steppe nomads :

Russian culture and people were much influenced by the Asian nomads

in the Russian steppe and the adjoining steppes and deserts. The

steppe culture of Russia was shaped in Russia through cross-cultural

contact mostly by Slavic, Tatar-Turkic, Mongolian and Iranian people.

In addition to ethnicity, also instruments such as the domra, traditional

costumes such as kaftan, sarafan, Russian Cossack and tea culture

were strongly influenced by the culture of Asian nomadic peoples.

The Eurasian steppes play a major role in Russia's more than 1000-year-old

history, so that the steppes are a subject of many Russian folk

songs.

Historical

peoples and nations :

• Thracians 15th-3rd centuries BC

• Chorasmia 13th–3rd centuries BC

• Cimmerians 12th–7th centuries BC

• Magyars 11th century BC – 8th century AD

• Scythians 8th–4th centuries BC

•

Sogdiana 8th–4th centuries BC

• Issedones 7th–1st century BC

• Massagatae 7th–1st century BC

• Thyssagetae 7th–3rd century BC

• Donghu 7th – 2nd century BC

• Dahae 7th BC-5th century AD

• Saka 6th–1st centuries BC

• Sarmatians 5th century BC – 5th century AD

• Bulgars 7th century BC–7th century AD

• Transoxiana 4th century BC – 14th century

AD

• Xiongnu 3rd century BC – 2nd century AD

• Iazyges 3rd century BC – 5th century AD

• Yuezhi 2nd century BC – 1st century AD

• Tauri

• Wusun 1st century BC – 6th century AD

• Xianbei 1st–3rd centuries

• Goths 3rd–6th centuries

• Vandals 2nd–5th centuries

• Visigoths 3rd–5th centuries

• Franks 3rd–8th centuries

• Huns 4th–8th centuries

• Ostrogoths 4th–8th centuries

• Early Slavs 5th-10th centuries

• Alans 5th–11th centuries

• Avars 5th–9th centuries

• Hepthalites 5th–7th centuries

• Eurasian Avars 6th–8th centuries

• Göktürks 6th–8th centuries

• Sabirs 6th–8th centuries

• Khazars 7th–11th centuries

• Onogurs 8th century

• Pechenegs 8th–11th centuries

• Bashkirs 10th century-present day

• Kipchaks and Cumans 11th–13th centuries

• Crimean Goths

• Mongol Empire 13th–14th centuries

• Tsagadai Ulus 13th–15th centuries

• Golden Horde 13th–15th centuries

• Cossacks, Kalmyks, Crimean Khanate, Volga Tatars,

Nogais and other Turkic states and tribes 15th–18th centuries

• Russian Empire 18th–20th centuries

• Soviet Union 20th century

• Gagauzia, Kazakhstan, Russian Federation, Ukraine,

Xinjiang 20th–21st centuries

• Mamluk Sultanate (Cairo) 13th-16th centuries

Source

:

https://en.wikipedia.org/

wiki/Eurasian_Steppe

_no_borders.png)

.svg.png)