| GERMANIC

Roman bronze statuette representing a Germanic man with his hair in a Suebian knot The Germanic peoples (from Latin: Germani) are a category of north European ethnic groups, first mentioned by Graeco-Roman authors. They are also associated with Germanic languages, which originated and dispersed among them, and are one of several criteria used to define Germanic ethnicity.

Although the English language possesses the adjective Germanic as distinct from German, it lacks an equivalent distinct noun. The terms Germanic peoples and Germani are therefore used by modern English-speaking scholars to avoid confusion with the inhabitants of present-day Germany ("Deutschland"), including the modern "German" ("Deutsche") people and language.

Starting with Julius Caesar (100–44 BCE), several Roman Empire authors placed their homeland, Germania, roughly between the Lower Rhine (west) and the Vistula Rivers (east), and distinguished them from other broad categories of peoples better known to Rome, especially the Celtic Gauls to their southwest, and "Scythian" Sarmatians to their further east and southeast. Greek writers, in contrast, consistently categorized the Germanic peoples from east of the Rhine as Gauls. And with the possible exception of some groups near the Rhine, there is no evidence that the Germanic peoples called themselves or their lands "Germanic". Latin and Greek writers report centuries of historical interactions with Germanic peoples on the Rhine and Danube River border regions, but from about 400, several long-established Germanic peoples on the Middle Danube were replaced by newcomers migrating from the further north or east of Europe. The description of peoples as Germanic in late antiquity was mainly restricted to those in the Rhine region, and thus referred to the Franks especially, and sometimes also the Alamanni.

Broader modern definitions of the Germanic peoples include peoples who were not known as Germani or Germanic peoples in their own time, but who are treated as one group of cultures, mostly because of their use of Germanic languages. Thus, in modern writing, "Germanic peoples" is a term which commonly includes peoples who were not referred to as Germanic by their contemporaries, and spoke distinct languages, only categorized as Germanic in modern times. Examples include the late Roman era Goths, and the Norse-speaking Vikings from Scandinavia.

The languages of the earliest known Germanic peoples of classical antiquity have left only fragmentary evidence. The first long texts which have survived were written outside Germania in the Gothic language from the region that is today Ukraine. Languages in this family are widespread today in Europe, and have dispersed worldwide, the family being represented by major modern languages such as English, Dutch, Nordic languages and German. The Eastern Germanic branch of the Germanic language family, once found in what is now Poland and Ukraine, is extinct.

Apart from language and geography, proposed connections between the diverse Germanic peoples described by classical and medieval sources, archaeology, and linguistics are the subject of ongoing debate among scholars :

•

On the one hand

there is doubt about whether late Roman-era Germanic peoples should

be treated as unified by any single unique shared culture, collective

consciousness, or even language. For example, the tendency of some

historians to describe late Roman historical events in terms of

Germanic language speakers has been criticized by other scholars

because it implies a single coordinated group. Walter Goffart has

gone so far as to suggest that historians should avoid the term

when discussing that period.

Definitions

of Germanic peoples :

•

Geography : The

Germanic peoples are seen as peoples who originated, before Caesar's

time, from somewhere between the Lower Rhine and Lower Vistula,

so-called "Germania". For Caesar, use of this definition

required knowing which people moved away from this homeland.

Such modern definitions have focused attention upon uncertainties and disagreements about the ethnic origins and backgrounds of both early Roman-era Germanic peoples, and late-Roman Germanic peoples.

Roman

ethnographic writing, from Caesar to Tacitus :

Rome had suffered a history of Gaulish invasions from the distant north, including those by the Cimbri, whom they had previously categorized as Gauls. Caesar, while describing his subsequent use of Roman soldiers deep in Gaulish territory, categorized the Cimbri, together with the peoples allied under Ariovistus, not as Gaulish, but as "Germanic", apparently using an ethnic term that was more local to the Rhine region where he fought Ariovistus. Modern scholars are undecided about whether the Cimbri were Germanic speakers like the Suevians, and even where exactly they lived in northern Europe, though it is likely to have been in or near Jutland. Caesar thus proposed that these more distant peoples were the cause of invasions into Italy. His solution was controlling Gaul, and defending the Rhine as a boundary against these Germani.

Several Roman writers—Strabo (about 63 BCE – 24 CE), Pliny the Elder (about 23–79 CE), and especially Tacitus (about 56–120 CE)—followed Caesar's tradition in the next few generations, by partly defining the Germanic peoples of their time geographically, according to their presumed homeland. This "Germania magna", or Greater Germania, was seen as a large wild country roughly east of the Rhine, and north of the Danube, but not everyone from within the area bounded by those rivers was ever described by Roman authors as Germanic, and not all Germani lived there. The opening of Tacitus's Germania gave a rough definition only :

Germania is separated from the Gauls, the Rhaetians, and Pannonii, by the rivers Rhine and Danube. Mountain ranges, or the fear which each feels for the other, divide it from the Sarmatians and Dacians.

It is the northern part of Greater Germania, including the North European Plain, Southern Scandinavia, and the Baltic coast that was presumed to be the original Germanic homeland by early Roman authors such as Caesar and Tacitus. (Modern scholars also see the central part of this area, between the Elbe and the Oder, as the region from which Germanic languages dispersed.) In the east, Germania magna's boundaries were unclear according to Tacitus, although geographers such as Ptolemy and Pomponius Mela took it to be the Vistula. For Tacitus the boundaries of Germania stretched further, to somewhere east of the Baltic Sea in the north, and its people blended with the "Scythian" (or Sarmatian) steppe peoples in the area of today's Ukraine in the south. In the north, greater Germania stretched all the way to the relatively unknown Arctic Ocean. In contrast, in the south of Greater Germania nearer the Danube, the Germanic peoples were seen by these Roman writers as immigrants or conquerors, living among other peoples whom they had come to dominate. More specifically, Tacitus noted various Suevian Germanic-speaking peoples from the Elbe river in the north, such as the Marcomanni and Quadi, pushing into the Hercynian forest regions towards the Danube, where the Gaulish Volcae, Helvetii and Boii had lived.

Roman writers who added to Caesar's theoretical description, especially Tacitus, also at least partly defined the Germani by non-geographic criteria such as their economy, religion, clothing, and language. Caesar had, for example, previously noted that the Germani had no druids, and were less interested in farming than Gauls, and also that Gaulish (lingua gallica) was a language the Germanic King Ariovistus had to learn. Tacitus mentioned Germanic languages at least three times, each mention concerning eastern peoples whose ethnicity was uncertain, and such remarks are seen by some modern authors as evidence of a unifying Germanic language. His comments are not detailed, but they indicate that there were Suevian languages (plural) within the category of Germanic languages, and that customs varied between different Germanic peoples. For example :

•

The Marsigni

and Buri, near today's southern Silesia, were Suevian in speech

and culture and therefore among the Germani in a region where he

says non-Germanic people also lived.

Origin

of the "Germanic" terminology :

The two main types of "Germani" in the time of Julius

Caesar. (Approximate positions only.) Later Roman imperial provinces

shown with red shading. On the Rhine are Germania Inferior (north)

and Germania Superior (south).

The older concept of the Germani being local to the Rhine, and especially the west bank of the lower Rhine, remained common among Graeco-Roman writers for a longer time than the more theoretical and general concept of Caesar. Cassius Dio writing in Greek in the 3rd century, consistently called the right-bank Germani of Caesar, the Celts and their country Keltike. Cassius contrasted them with the "Gauls" on the left bank of the Rhine, and described Caesar doing the same in a speech. He reported that the peoples on either side of the Rhine had long ago taken to using these contrasting names, treating it as a boundary, but "very anciently both peoples dwelling on either side of the river were called Celts". For Cassius Dio, the only Germani and the only Germania were west of the Rhine within the empire: "some of the Celts (Keltoí), whom we call Germans (Germanoí)", had "occupied all the Belgic territory [Belgike] along the Rhine and caused it to be called Germany [Germanía]".

At least two well-read 6th century Byzantine writers, Agathias and Procopius, understood the Franks on the Rhine to effectively be the old Germani under a new name, since, as Agathias wrote, they inhabit the banks of the Rhine and the surrounding territory.

Germanic

terminology before Caesar :

•

One is the use

of the word Germani in a report describing lost writings of Posidonius

(about 135 – 51 BCE), made by the much later writer Athenaios

(around 190 CE); however, this word may have been added by the later

writer, and if not, probably referred to the Germani cisrhenani.

It says only that the Germani eat roasted meat in separate joints,

and drink milk and unmixed wine.

Later

Roman "Germanic peoples" :

It seems clear that in the fourth century 'German' was no longer a term which included all western barbarians. Ammianus Marcellinus, in the later fourth century, uses Germania only when he is referring to the Roman provinces of Upper Germany and Lower Germany; east of Germania are Alamannia and Francia.

As an exceptional case, the poet Sidonius Apollinaris, living in what is now southern France, described the Burgundians of his time as speaking a "Germanic" tongue and being "Germani". Wolfram has proposed that this word was chosen not because of a comparison of languages, but because the Burgundians had come from the Rhine region, and even argued that the use of this word by Sidonius might be seen as evidence against Burgundians being speakers of East Germanic, given that the East Germanic-speaking Goths, also present in southern France at this time, were never described this way.

Far from the Rhine, the Gothic peoples in what is today Ukraine, and the Anglo-Saxons in the British Isles, were called Germanic in only one surviving classical text, by Zosimus (5th century), but this was an instance in which he mistakenly believed he was writing about Rhineland peoples. Otherwise, Goths and similar peoples such as the Gepids, were consistently described as Scythian.

Medieval

loss of the "Germanic people" concept :

Medieval writers in western Europe used Caesar's old geographical concept of Germania, which, like the new Frankish and clerical jurisdictions of their time, used the Rhine as a frontier marker, although they did not commonly refer to any contemporary Germani. For example, Louis the German (Ludovicus Germanicus) was named this way because he ruled east of the Rhine, and in contrast the kingdom west of the Rhine was still called Gallia (Gaul) in scholarly Latin.

Writers using Latin in West Germanic-speaking areas did recognize that those languages were related (Dutch, English, Lombardic, and German). To describe this fact they referred to "Teutonic" words and languages, seeing the nominative as a Latin translation of Theodiscus, which was a concept that West Germanic speakers used to refer to themselves. It is the source of the modern words "Dutch", German "Deutsch", and Italian "Tedesco". Romance language speakers and others such as the Welsh were contrasted using words based on another old word, Walhaz, the source of "Welsh", Wallach, Welsch, Walloon, etc., itself derived from the name of the Volcae, a Celtic group. Only a small number of writers were influenced by Tacitus, whose work was known at Fulda Abbey, and few used terminology such as lingua Germanica instead of theudiscus sermo.

On the other hand, there were several more origin myths written after Jordanes which similarly connected some of the post Roman peoples to a common origin in Scandinavia. As pointed out by Walter Pohl, Paul the Deacon even implied that the Goths, like the Lombards, descended from "Germanic peoples", though it is unclear if they continued to be "Germanic" after leaving the north. Frechulf of Lisieux observed that some of his contemporaries believed that the Goths might belong to the "nationes Theotistae", like the Franks, and that both the Franks and the Goths might have come from Scandinavia. It is in this period, the 9th century Carolingian era, that scholars also first recorded speculation about relationships between Gothic and West Germanic languages. Smaragdus of Saint-Mihiel believed the Goths spoke a teodisca lingua like the Franks, and Walafrid Strabo, calling it a theotiscus sermo, was even aware of their Bible translation. However, though the similarities were noticed, Gothic would not have been intelligible to a West Germanic speaker.

The first detailed origins legend of the Anglo-Saxons was by Bede (died 735), and in his case he named the Angles and Saxons of Britain as peoples who once lived in Germania, like, he says, the Frisians, Rugians, Danes, Huns, Old Saxons (Antiqui Saxones) and the Bructeri. He even says that British people still call them, corruptly, "Garmani". As with Jordanes and the Gutones, there is other evidence, linguistic and archaeological, which is consistent with his scholarly account, although this does not prove that Bede's non-scholarly contemporaries had accurate knowledge of historical details.

In western Europe then, there was limited scholarly awareness of the Tacitean "Germanic peoples", and even their potential connection to the Goths, but much more common was adherence to Caesar's concept of the geographical meaning of Germania east of the Rhine, and a perception of similarities between some Germanic languages – though they were not given this name until much later.

Later

debates :

Very influentially, Jordanes called Scandinavia a "womb of nations" (vagina nationum), asserting that many peoples came from there in prehistoric times. This idea influenced later origin legends including the Lombard origin story, written by Paul the Deacon (8th century) who opens his work with an explanation of the theory. During the Carolingian renaissance he and other scholars even sometimes used the Germanic terminology. (See below.) The Scandinavian origin theme was still influential in medieval times and has even been influential in early modern speculations about Germanic peoples, for example in proposals about the origins of not only Goths and Gepids, but also of Rugians and Burgundians.

The citing of Jordanes and similar writers to attempt to prove that the Goths were "Germanic" in more than language continues to arouse debate among scholars, because while his work is unreliable, the Baltic connection on its own is consistent with linguistic and archaeological evidence. However, Walter Goffart in particular has criticized the methodology of many modern scholars for using Jordanes and other origins stories as independent sources of real tribal memories, but only when it matches their beliefs arrived at in other ways.

Modern debates :

An 1884 painting of Arminius and Thusnelda by German illustrator Johannes Gehrts. The artwork depicts Arminius saying farewell to his beloved wife before he goes off into battle During the Renaissance there was a rediscovery and renewed interest in secular writings of classical antiquity. By the late 15th century, Tacitus had become a focus of interest all around Europe, and, among other effects, this revolutionized ideas in Germany concerning the history of Germany itself. Tacitus continues to be an important influence in Germanic studies of antiquity, and is often read together with the Getica of Jordanes, who wrote much later.

Tacitus's ethnography won the attention it had formerly been denied because there now was a Germany, the "German nation" that had come into existence since the Carolingians, which Tacitus could now equip with a heaven-sent ancient dignity and pedigree.

In this context, in the 19th century, the famous folklorist and linguist Jacob Grimm helped popularize the concept of Germanic languages as well as of Indo-european languages. Apart from the well-known Grimm's Fairy Tales, collected with his brother Wilhelm, he published, for example, Deutsche Mythologie attempting to reconstruct Germanic mythology, and a German dictionary, Deutsches Wörterbuch, with detailed etymological proposals attempting to reconstruct the oldest Germanic language. He also popularized a ne0w idea of these Germanic speakers, especially those in Germany, as clinging valiantly to their supposed Germanic civilization over the centuries.

The subsequent popular modern assertion of strong cultural continuity between Roman-era Germani and medieval or modern Germanic speakers, especially Germans, assumed a strong connection between a family trees of language categories, and both cultural and racial heritages. The name of the newly defined language family, Germanic, was long unpopular in other countries such as England, where the medieval "Teutonic" was seen as less potentially misleading. Similarly, in Denmark "Gothic" was sometimes used as a term for the language group uniting the Germani and the Goths, and a modified Gothonic was proposed by Gudmund Schütte and used locally.

This romanticist, nationalist approach has been rejected by scholars in its simplest forms since approximately World War II. For example, the once common habit of referring to Roman-era Germanic peoples as "Germans" is discouraged by modern historians, and modern Germans are no longer seen as the main successors of the Germani. Not only are ideas associated with Nazism now criticized, but also other romanticized ideas about the Germanic peoples. For example, Guy Halsall has mentioned the popularity of the "view of the peoples of Germania as, essentially, proto-democratic communes of freemen". Peter Heather has pointed out as well that the Marxist theory "that some of Europe's barbarians were ultimately responsible for moving Europe onwards to the feudal model of production has also lost much of its force".

Further, some historians now question whether there was any unifying Germanic culture even in Roman times, and secondly whether there was any significant continuity at all apart from language, connecting the Roman era Germanic peoples with the mixed new ethnic groups who formed in late antiquity. Sceptics of such connections include Walter Goffart, and others associated with him and the University of Toronto. Goffart lists four "contentions" about how the Germanic terminology biases the conclusions of historians, and is therefore misleading :

1.

Barbarian invasions should not be seen as a single collective movement.

Different barbarian groups moved for their own reasons under their

own leaders.

Peter Heather for example, continues to use the Germanic terminology but writes that concerning proposals of Germanic continuity, "all subsequent discussion has accepted and started from Wenskus's basic observations" and "the Germani in the first millenium were thus not closed groups with continuous histories". Heather however believes that such caution now often goes too far in denying any large scale movements of people in specific cases, as exemplified by Patrick Amory's explanation of the Ostrogoths and their Kingdom of Italy.

Another proponent of relatively significant continuity, Wolf Liebeschuetz, has argued that the shared use of Germanic languages by, for example, Anglo-Saxons and Goths, implies that they must have had more links to Germania than only language. While little concrete evidence has survived, Liebeschuetz proposes that the existence of Weregild laws, stipulating compensation payments to avoid blood feuds, must have been of Germanic origin because such laws were not Roman. Liebeschuetz also argues that recent sceptical scholars "deprive the ancient Germans and their constituent tribes of any continuous identity" and this is "important" because it makes European history a product of Roman history, not "a joint creation of Roman and Germans".

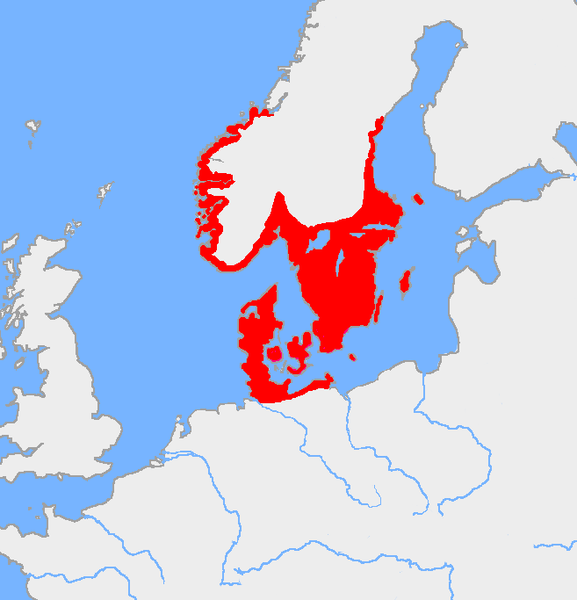

Map of the Nordic Bronze Age culture, around 1200 BCE Prehistoric evidence :

Archaeological evidence :

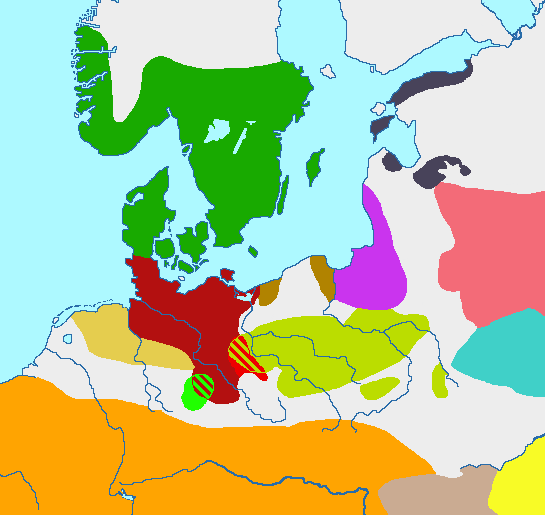

Archeological cultures of Northern Europe in the late Pre-Roman Iron Age :

Archaeologists divide the area of Roman-era Germania into several Iron Age "material cultures". At the time of Caesar, all had been under the strong influence of the La Tène culture, an old culture in the south and west of Germania, which is strongly associated with Celtic-speaking Gauls, including those in Gaul itself. These La Tène peoples, who included the Germani cisrhenani, are generally considered unlikely to have spoken Germanic languages as defined today, though some may have spoken unknown related languages or Celtic dialects. To the north of these zones however, in southern Scandinavia and northern Germany, the archaeological cultures started to become more distinct from La Tène culture during the Iron Age.

Concerning Germanic speakers within these northern regions, the relatively well-defined Jastorf culture matches the areas described by Tacitus, Pliny the elder and Strabo as Suevian homelands near the lower River Elbe, and stretching east on the Baltic coast to the Oder river. The Suevian peoples are seen by scholars as early West Germanic speakers. There is no consensus about whether neighbouring cultures in Scandinavia, Poland, and northwestern Germany were also part of a Germanic (or proto-Germanic)-speaking community at first, but this group of cultures were related to each other, and in contact. To the west of the Elbe for example, on what is now the German North Sea coast, was the so-called Harpstedt-Nienburger Group between the Jastorf culture and the La Tène influenced cultures of the Lower Rhine. To the east in what is now northern Poland was the Oksywie culture, later becoming the Wielbark culture with the arrival of Jastorf influences, probably representing the entry of East Germanic speakers. Related also to these and the Jastorf culture was the Przeworsk culture in southern Poland. It began as strongly La Tène-influenced local culture, and apparently became at least partly Germanic-speaking.

The Jastorf culture came into direct contact with La Tène cultures on the upper Elbe and Oder rivers, believed to correspond to the Celtic-speaking peoples such as the Boii and Volcae described in this area by Roman sources. In the south of their range, the Jastorf and Przeworsk material cultures spread together, in several directions.

Caesar's

claims :

And there was formerly a time when the Gauls excelled the Germans [Germani] in prowess, and waged war on them offensively, and, on account of the great number of their people and the insufficiency of their land, sent colonies over the Rhine. Accordingly, the Volcae Tectosages, seized on those parts of Germany which are the most fruitful [and lie] around the Hercynian forest, (which, I perceive, was known by report to Eratosthenes and some other Greeks, and which they call Orcynia), and settled there.

Modern archaeologists, having found no sign of such movements, see the Gaulish La Tène culture as native to what is now southern Germany, and the La Tène-influenced cultures on both sides of the Lower Rhine in this period as quite distinct from the Elbe Germanic peoples, well into Roman times. On the other hand, the account of Caesar finds broad agreement with the archaeological record of the Celtic La Tène culture first expanding to the north, influencing all cultures there, and then suddenly having a weaker influence in that area. Subsequently, the Jastorf culture expanded in all directions from the region between the lower Elbe and Oder rivers.

Languages

:

Between around 500 BCE and the beginning of the Common Era, archeological and linguistic evidence suggest that the Urheimat ('original homeland') of the Proto-Germanic language, the ancestral idiom of all attested Germanic dialects, was primarily situated in an area corresponding to the extent of the Jastorf culture. One piece of evidence is the presence of early Germanic loanwords in the Finnic and Sámi languages (e.g. Finnic kuningas, from Proto-Germanic *kuningaz 'king'; rengas, from *hringaz ‘ring’; etc.), with the older loan layers possibly dating back to an earlier period of intense contacts between pre-Germanic and Finno-Permic (i.e., Finno-Samic) speakers. An archeological continuity can also be demonstrated between the Jastof culture and populations described as Germanic by Roman sources.

Although Proto-Germanic is reconstructed dialect-free via the comparative method, it is almost certain that it was never a uniform proto-language. The late Jastorf culture occupied so much territory that it is unlikely that Germanic populations spoke a single dialect, and traces of early linguistic varieties have been highlighted by scholars.Sister dialects of Proto-Germanic itself certainly existed, as evidenced by some recorded Germanic proper names not following Grimm's law, and the reconstructed Proto-Germanic language was only one among several dialects spoken at that time by peoples identified as "Germanic" in Roman sources or archeological data.

Attestation

:

The inscription on the Negau helmet B, carved in the Etruscan alphabet during the 3rd–2nd c. BCE, is generally regarded as Proto-Germanic The origin of the Germanic runes remains controversial, although it has been stated that they bear a more formal resemblance to North Italic alphabets (especially the Camunic alphabet; 1st mill. BCE) than to Latin letters.They are not attested before the beginning of the Common Era in southern Scandinavia, and the connection between the two alphabets is therefore uncertain. In the absence of earlier evidence, it must be assumed that Proto-Germanic speakers living in Germania were members of preliterate societies. The only pre-Roman inscription that could be interpreted as Proto-Germanic, written in the Etruscan alphabet, has not been found in Germania but rather in the Venetic region. The inscription, engraved on the Negau helmet in the 3rd–2nd centuries BCE, possibly by a Germanic-speaking warrior involved in combat in northern Italy, has been interpreted by some scholars as Harigasti Teiw? (*harja-gastiz 'army-guest' + *teiwaz '(war-)god'), which could be an invocation to a war-god or a mark of ownership engraved by its possessor. The inscription Fariarix (*farjon- 'ferry' + *rik- 'ruler') carved on tetradrachms found in Bratislava (mid-1st c. BCE) may indicate the Germanic name of a Celtic ruler.

The earliest attested runic inscriptions (Vimose comb, Øvre Stabu spearhead), initially concentrated in modern Denmark and written with the Elder Futhark system, are dated to the second half of the 2nd century CE. Their language, named Primitive Norse, Proto-Norse, or similar terms, and still very close to Proto-Germanic, has been interpreted as a northern variant of the Northwest Germanic dialects and the ancestor of the Old Norse language of the Viking Age (8th–11th c. CE). Based upon its dialect-free character and shared features with West Germanic languages, some scholars have contended that it served as a kind of koiné language. The merging of unstressed Proto-Germanic vowels, attested in runic inscriptions from the 4th and 5th centuries CE, also suggests that Primitive Norse could not have been a direct predecessor of West Germanic dialects.

Disintegration

:

In the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE, migrations of East Germanic gentes from the Baltic Sea coast southeastwards into the hinterland led to their separation from the dialect continuum. By the late 3rd century CE, linguistic divergences like the West Germanic loss of the final consonant -z had already occurred within the "residual" Northwest dialect continuum, which definitely ended after the 5th- and 6th-century migrations of Angles, Jutes and part of Saxon groups towards modern-day England.

Classification

:

• Proto-Germanic: estimated to have been spoken approximatively between the mid-1st millennium BCE (Jastorf culture) and the mid-1st millennium CE (Migration Period).

Classical

subdivisions :

•

Ingvaeones, nearest

to the Ocean.

Pliny the Elder, somewhat similarly, named five races of Germani in his Historia Naturalis, with the same basic three groups as Tacitus, plus two more eastern blocks of Germans, the Vandals, and further east the Bastarnae. He clarifies that the Istvaeones are near the Rhine, although he gives only one problematic example, the Cimbri. He also clarifies that the Suevi, though numerous, are actually in one of the three Mannus groups. His list :

•

The Vandili,

include the Burgundiones, the Varini, the Carini, and the Gutones.

The Varini are listed by Tacitus as being Suevic, and the Gutones

are described by him as Germanic, leaving open the question of whether

they are Suevian.

Strabo, who focused mainly on Germani between the Elbe and Rhine, and does not mention the sons of Mannus, also set apart the names of Germani who are not Suevian, in two other groups, similarly implying three main divisions: "smaller German tribes, as the Cherusci, Chatti, Gamabrivi, Chattuarii, and next the ocean the Sicambri, Chaubi, Bructeri, Cimbri, Cauci, Caulci, Campsiani".

From the perspective of modern linguistic reconstructions, the classical ethnographers were not helpful in distinguishing two large groups that spoke types of Germanic very different from the Suevians and their neighbours, whose languages are the source of modern West Germanic.

•

The Germanic

peoples of the far north, in Scandinavia, were treated as Suevians

by Tacitus, though their Germanic dialects would evolve into Proto

Norse, and later Old Norse, as spoken by the Vikings, and then the

North Germanic language family of today.

History

:

The Bastarnae or Peucini are mentioned in historical sources going back as far as the 3rd century BCE through the 4th century CE. These Bastarnae were described by Greek and Roman authors as living in the territory east of the Carpathian Mountains north of the Danube's delta at the Black Sea. They were variously described as Celtic or Scythian, but much later Tacitus, in disagreement with Livy, said they were similar to the Germani in language. According to some authors then, they were the first Germani to reach the Greco-Roman world and the Black Sea area.

In 201–202 BCE, the Macedonians, under the leadership of King Philip V, conscripted the Bastarnae as soldiers to fight against the Roman Republic in the Second Macedonian War. They remained a presence in that area until late in the Roman Empire. The Peucini were a part of this people who lived on Peuce Island, at the mouth of the Danube on the Black Sea. King Perseus enlisted the service of the Bastarnae in 171–168 BCE to fight the Third Macedonian War. By 29 BCE, they were subdued by the Romans and those that remained presumably merged into various groups of Goths into the second century CE.

Another eastern people known from about 200 BCE and sometimes believed to be Germanic-speaking, are the Scirii, because they appear in a record in Olbia on the Black Sea which records that the city had been troubled by Scythians, Sciri and Galatians. There is a theory that their name, perhaps meaning pure, was intended to contrast with the Bastarnae, perhaps meaning mixed, or "bastards". Much later, Pliny the Elder placed them to the north near the Vistula together with an otherwise unknown people called the Hirrii. The Hirrii are sometimes equated with the Harii mentioned by Tacitus in this region, whom he considered to be Germanic Lugians. These names have also been compared to that of the Heruli, who are another people from the area of modern Ukraine, believed to have been Germanic. In later centuries the Scirii, like the Heruli, and many of the Goths, were among the peoples who allied with Attila and settled in the Middle Danube, Pannonian region.

Cimbrian War (2nd century BCE) :

Migrations of the Cimbri and the Teutons (late 2nd century BCE) and their war with Rome (113 – 101 BCE) Late in the 2nd century BCE, Roman and Greek sources recount the migrations of the far northern "Gauls", the Cimbri, Teutones and Ambrones. Caesar later classified them as Germanic. They first appeared in eastern Europe where some researchers propose they may have been in contact with the Bastarnae and Scordisci. In 113 BCE, they defeated the Boii at the Battle of Noreia in Noricum.

Their movements through parts of Gaul, Italy and Hispania resulted in the Cimbrian War between these groups and the Roman Republic, led primarily by its Consul, Gaius Marius.

In

Gaul, a combined force of Cimbri and Teutoni and others defeated

the Romans in the Battle of Burdigala (107 BCE) at Bordeaux, in

the Battle of Arausio (105) at Orange in France, and in the Battle

of Tridentum (102) at Trento in Italy. Their further incursions

into Roman Italy were repelled by the Romans at the Battle of Aquae

Sextiae (Aix-en-Provence) in 102 BCE, and the Battle of Vercellae

in 101 BCE (in Vercelli in Piedmont).

Germano-Roman

contacts :

•

63 BCE Ariovistus,

described by Caesar as Germanic, led mixed forces over the Rhine

into Gaul as an ally of the Sequani and Averni in their battle against

the Aedui, who they defeated at the Battle of Magetobriga. He stayed

there on the west of the Rhine. He was also accepted as an ally

by the Roman senate.

Julio-Claudian dynasty (27 BCE – 68 CE) and the Year of Four Emperors (69 CE) :

During the reign of Augustus from 27 BCE until 14 CE, the Roman empire became established in Gaul, with the Rhine as a border. This empire made costly campaigns to pacify and control the large region between the Rhine and Elbe. In the reign of his successor Tiberius it became state policy to leave the border at the Rhine, and expand the empire no further in that direction. The Julio-Claudian dynasty, the extended family of Augustus, paid close personal attention to management of this Germanic frontier, establishing a tradition followed by many future emperors. Major campaigns were led from the Rhine personally by Nero Claudius Drusus, step-son of Augustus, then by his brother the future emperor Tiberius; next by the son of Drusus, Germanicus (father of the future emperor Caligula and grandfather of Nero).

In 38 BCE, Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, consul of Transalpine Gaul, became the second Roman to lead forces over the Rhine. In 31 BCE Gaius Carrinas repulsed an attack by Suevi from east of the Rhine. In 25 BCE Marcus Vinicius took vengeance on some Germani in Germania, who had killed Roman traders. In 17/16 BCE at the Battle of Bibracte the Sugambri, Usipetes, and Tencteri crossed the Rhine and defeated the 5th legion under Marcus Lollius, capturing the legion's eagle.

From 13 BCE until 17 CE there were major Roman campaigns across the Rhine nearly every year, often led by members of the family of Augustus. First came the pacification of the Usipetes, Sicambri, and Frisians near the Rhine, then attacks increased further from the Rhine, on the Chauci, Cherusci, Chatti and Suevi (including the Marcomanni). These campaigns eventually reached and even crossed the Elbe, and in 5 CE Tiberius was able to show strength by having a Roman fleet enter the Elbe and meet the legions in the heart of Germania. However, within this period two Germanic kings formed large anti-Roman alliances. Both of them had spent some of their youth in Rome :

•

After 9 BCE,

Maroboduus of the Marcomanni had led his people away from the Roman

activities into the Bohemian area, which was defended by forests

and mountains, and formed alliances with other peoples. Tacitus

referred to him as king of the Suevians. In 6 CE Rome planned an

attack but forces were needed for the Illyrian revolt in the Balkans,

until 9 CE, at which time another problem arose in the north...

The Julio-Claudian dynasty also recruited northern Germanic warriors, particularly men of the Batavi, as personal bodyguards to the Roman emperor, forming the so-called Numerus Batavorum. After the end of the dynasty, in 69 AD, the Batavian bodyguard were dissolved by Galba in 68 because of its loyalty to the old dynasty. The decision caused deep offense to the Batavi, and contributed to the outbreak of the Revolt of the Batavi in the following year which united Germani and Gauls, all connected to Rome but living both within the empire and outside it, over the Rhine. Their indirect successors were the Equites singulares Augusti which were, likewise, mainly recruited from the Germani. They were apparently so similar to the Julio-Claudians' earlier German Bodyguard that they were given the same nickname, the "Batavi". Gaius Julius Civilis, a Roman military officer of Batavian origin, orchestrated the Revolt. The revolt lasted nearly a year and was ultimately unsuccessful.

Flavian

and Antonine dynasties (70 – 192 CE) :

Distribution of Germanic, Venedi (Slavic), and Sarmatian (Iranian) groups on the frontier of the Roman Empire, 125 AD The Marcomannic Wars during the time of Marcus Aurelius ended in approximately 180 CE. Dio Cassius called it the war against the Germani, noting that Germani was the term used for people who dwell up in those parts (in the north). A large number of peoples from north of the Danube were involved, not all Germanic-speaking, and there is much speculation about what events or plans led to this situation. Many scholars believe causative pressure was being created by aggressive movements of peoples further north, for example with the apparent expansion of the Wielbark culture of the Vistula, probably representing Gothic peoples who may have pressured Vandal peoples towards the Danube.

•

In 162 the Chatti

once again attacked the Roman provinces of Raetia (with its capital

at Augsburg) and Germania Superior to their south. During the main

war in 973 they were repulsed from the Rhine frontier to their west,

along with their neighbours the Suevian Hermunduri.

After these Marcomannic wars, the Middle Danube began to change, and in the next century the peoples living there tended to be referred to as Gothic, rather than Germanic.

New

names on the frontiers (170 – 370) :

Secondly, soon after the appearance of the Alamanni on the Upper Rhine, the Franks began to be mentioned as occupying the land at the bend of the lower Rhine. In this case, the collective name was new, but the original peoples who composed the group were largely local, and their old names were still mentioned occasionally. The Franks were still sometimes called Germani as well.

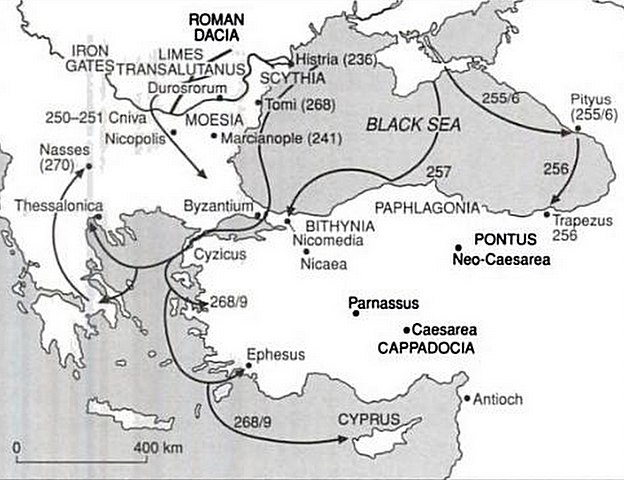

Gothic invasions of the Roman Empire in the 3rd century Thirdly, the Goths and other "Gothic peoples" from the area of today's Poland and Ukraine, many of whom were Germanic-speaking peoples, began to appear in records of this period.

•

In 238, Goths

crossed the Danube and invaded Histria. The Romans made an agreement

with them, giving them payment and receiving prisoners in exchange.

The Dacian Carpi, who had been paid off by the Romans before then,

complained to the Romans that they were more powerful than the Goths.

•

In the 270s the

emperor Probus fought several Germanic peoples who breached territory

on both the Rhine and the Danube, and tried to maintain Roman control

over the Agri Decumates. He fought not only the Franks and Alamanni,

but also Vandal and Burgundian groups now apparently near the Danube.

By 369, the Romans appear to have ceded their large province of Dacia to the Tervingi, Taifals and Victohali.

Migration

Period (ca. 375 – 568) :

Gothic

entry into the empire :

The Gothic wars were affected indirectly by the arrival of the nomadic Huns from Central Asia in the Ukrainian region. Some Gothic peoples, such as the Gepids and the Greuthungi (sometimes seen as predecessors of the later Ostrogoths), joined the newly forming Hunnish faction, and played a prominent role in the Hunnic Empire, where Gothic became a lingua franca. Based on the description of Socrates Scholasticus, Guy Halsall has argued that the Hunnish hegemony developed after a major campaign by Valens against the Goths, which had caused great damage, but failed to achieve a decisive victory. Peter Heather has argued that Socrates should be rejected on this point, as inconsistent with the testimony of Ammianus.

The Gothic Thervingi, under the leadership of Athanaric, had in any case borne the impact of the campaign of Valens, and were also losers against the Huns, but clients of Rome. A new faction under leadership of Fritigern, a Christian, were given asylum inside the Roman Empire in 376 CE. They crossed the Danube and became foederati. With the emperor occupied in the Middle East, the Tervingi were treated badly and becoming desperate; significant numbers of mounted Greuthungi, Alans and others were able to cross the river and support a Tervingian uprising leading to the massive Roman defeat at Adrianople.

Around 382, the Romans and the Goths now within the empire came to agreements about the terms under which the Goths should live. There is debate over the exact nature of such agreements, and for example whether they allowed the continuous semi-independent existence of pre-existing peoples; however the Goths do appear to have been allowed more privileges than in traditional settlements with such outside groups. One result of the comprehensive settlement was that the imperial army now had a larger number of Goths, including Gothic generals.

Imperial

turmoil :

Alaric was a Roman military commander of Gothic background, who first appears in the record in the time of Theodosius. After the death of Theodosius, he became one of the various Roman competitors for influence and power in the difficult situation. The forces he led were described as mixed barbarian forces, and clearly included many other people of Gothic background, a phenomenon which had become common in the Balkans. In an important turning point for Roman history, during the factional turmoil, his army came to act increasingly as an independent political entity within the Roman empire, and at some point he came to be referred to as their king, probably around 401 CE, when he lost his official Roman title. This is the origin of the Visigoths, whom the empire later allowed to settle in what is now southwestern France. While military units had often had their own ethnic history and symbolism, this is the first time that such a group established a new kingdom. There is disagreement about whether Alaric or his family had a royal background, but there is no doubt that this kingdom was a new entity, very different from any previous Gothic kingdoms.

Invasions

of 401 - 411 :

On the Danube, change was far more dramatic. In the words of Walter Goffart :

• Between 401 and 411, four distinct groups of barbarians – different from Alaric's Goths – invaded Roman territory, all apparently on one-way journeys, in large-scale efforts to transpose themselves onto imperial soil and not just plunder and return home.

The reasons that these invasions apparently all dispersed from the same area, the Middle Danube, are uncertain. It is most often argued that the Huns must have already started moving west, and consequently pressuring the Middle Danube. Peter Heather for example writes that around 400, "a highly explosive situation was building up in the Middle Danube, as Goths, Vandals, Alans and other refugees from the Huns moved west of the Carpathians" into the area of modern Hungary on the Roman frontier.

Walter Goffart, in contrast, has pointed out that there is no clear evidence of new eastern groups arriving in the area immediately before the great movements, and so it remains possible that the Huns moved West after these large groups had left the Middle Danube. Goffart's suggestion is that the example of the Goths, such as those led by Alaric, had set an example leading to a "common perception, however indistinct, that warriors could improve their condition by forcing their existence on the attention of the Empire, demanding to be dealt with, and exacting a part in the imperial enterprise."

Whatever the chain of events, the Middle Danube later became the centre of Attila's loose empire containing many East Germanic people from the east, who remained there after the death of Attila. The makeup of peoples in that area, previously the home of the Germanic Marcomanni, Quadi and non-Germanic Iazyges, changed completely in ways which had a significant impact on the Roman empire and its European neighbours. Thereafter, though the new peoples ruling this area still included Germanic-speakers, as discussed above, they were not described by Romans as Germani, but rather "Gothic peoples".

•

In 401, Claudian

mentions a Roman victory over a large force including Vandals, in

the province of Raëtia. It is possible that this group was

involved in the later crossing of the Rhine.

In 408, the eastern emperor Arcadius died, leaving a child as successor, and the west Roman military leader Stilicho was killed. Alaric, wanting a formal Roman command but unable to negotiate one, invaded Rome itself, twice, in 401 and 408.

Constantius III, who became Magister militum by 411, restored order step-by-step, eventually allowing the Visigoths to settle within the empire in southwest Gaul. He also committed to retaking control of Iberia, from the Rhine-crossing groups. When Constantius died in 421, having been co-emperor himself for one year, Honorius was the only emperor in the West. However, Honorius died in 423 without an heir. After this, the Western Roman empire steadily lost control of its provinces.

From Western Roman Empire to medieval kingdoms (420 – 568) :

This section needs additional citations for verification.

Coin of Odoacer, Ravenna, 477, with Odoacer in profile, depicted with a "barbarian" moustache

Germanic kingdoms in 526 CE

2nd century to 6th century simplified migrations The Western Roman Empire declined gradually in the 5th and 6th centuries, and the eastern emperors had only limited control over events in Italy and the western empire. Germanic speakers, who by now dominated the Roman military in Europe, and lived both inside and outside the empire, played many roles in this complex dynamic. Notably, as the old territory of the western empire came to be ruled on a regional basis, the barbarian military forces, ruled now by kings, took over administration with differing levels of success. With some exceptions, such as the Alans and Bretons, most of these new political entities identified themselves with a Germanic-speaking heritage.

In the 420s, Flavius Aëtius was a general who successfully used Hunnish forces on several occasions, fighting Roman factions and various barbarians including Goths and Franks. In 429 he was elevated to the rank of magister militum in the western empire, which eventually allowed him to gain control of much of its policy by 433. One of his first conflicts was with Boniface, a rebellious governor of the province of Africa in modern Tunisia and Libya. Both sides sought an alliance with the Vandals based in southern Spain who had acquired a fleet there. In this context, the Vandal and Alan kingdom of North Africa and the western Mediterranean would come into being.

In

433 Aëtius was in exile and spent time in the Hunnish domain.

Compared to Gaul, what happened in Roman Britain, which was similarly both isolated from Italy and heavily Romanized, is less clearly recorded. However the end result was similar, with a Germanic-speaking military class, the Anglo-Saxons, taking over administration of what remained of Roman society, and conflict between an unknown number of regional powers. While major parts of Gaul and Britain redefined themselves ethnically on the basis of their new rulers, as Francia and England, in England the main population also became Germanic-speaking. The exact reasons for the difference are uncertain, but significant levels of migration played a role.

In 476 Odoacer, a Roman soldier who came from the peoples of the Middle Danube in the aftermath of the Battle of Nedao, became King of Italy, removing the last of the western emperors from power. He was murdered and replaced in 493 by Theoderic the Great, described as King of the Ostrogoths, one of the most powerful Middle Danube peoples of the old Hun alliance. Theoderic had been raised up and supported by the eastern emperors, and his administration continued a sophisticated Roman administration, in cooperation with the traditional Roman senatorial class. Similarly, culturally Roman lifestyles continued in North Africa under the Vandals, in Savoy under the Burgundians, and within the Visigothic realm.

The Ostrogothic kingdom ended in 542 when the eastern emperor Justinian made a last great effort to reconquer the Western Mediterranean. The conflicts destroyed the Italian senatorial class, and the eastern empire was also unable to hold Italy for long. In 568 the Lombard king Alboin, a Suevian people who had entered the Middle Danubian region from the north conquering and partly absorbing the frontier peoples there, entered Italy and created the Italian Kingdom of the Lombards there. These Lombards now included Suevi, Heruli, Gepids, Bavarians, Bulgars, Avars, Saxons, Goths, and Thuringians. As Peter Heather has written these "peoples" were no longer peoples in any traditional sense.

Older accounts which describe a long period of massive movements of peoples and military invasions are oversimplified, and describe only specific incidents. According to Herwig Wolfram, the Germanic peoples did not and could not "conquer the more advanced Roman world" nor were they able to "restore it as a political and economic entity"; instead, he asserts that the empire's "universalism" was replaced by "tribal particularism" which gave way to "regional patriotism". The Germanic peoples who overran the Western Roman Empire probably numbered less than 100,000 people per group, including approximately 15,000-20,000 warriors. They constituted a tiny minority of the population in the lands over which they seized control.

Apart from the common history many of them had in the Roman military, and on Roman frontiers, a new and longer-term unifying factor for the new kingdoms was that by 500, the start of the Middle Ages, most of the old Western empire had converted to the same Rome-centred Catholic form of Christianity. A key turning point was the conversion of Clovis I in 508. Before this point, many of the Germanic kingdoms, such as those of the Goths and Burgundians, now adhered to Arian Christianity, a form of Christianity which they perhaps took up in the time of the Arian emperor Valens, but which was now considered a heresy.

Early Middle Ages :

Map showing area of Norse settlements during the Viking Age, including Norman conquests In the centuries after 568, the Visigothic kingdom, by now centred in Spain, was ended by the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in the 8th century. Much of continental catholic Europe became part of a greater Francia under the Merovingian and then the Carolingian dynasty, which began with Pepin the Short, the son of Charles Martel. Charles, though not a king, reconsolidated the Frankish kingdom's dominance over Saxons, Frisians, Bavarians and Burgundians, and defeated the Umayyads at the 732 Battle of Tours. Pepin's son Charlemagne conquered the Lombards in 774, and in an important turning point in European history, was crowned as emperor by Pope Leo III in Rome on Christmas Day, 800 CE. This consolidated a shift in the power structure from the south to the north, and was also a strong symbolic link to Rome and the Roman Christianity. The core of the new empire included what is now France, Germany and the Benelux countries. The empire laid the foundations for the medieval and early modern ancien regime, finally destroyed only by the French Revolution. The Frankish-Catholic way of doing politics and war and religion also had a strong effect upon all neighbouring regions, including what became England, Spain, Italy, Austria, and Bohemia.

The effect of old Germanic culture on this new Latin-using empire is a topic of dispute, because there was much continuity with the old Roman legal systems, and the increasingly important Christian religion. An example which is argued to show an influence of earlier Germanic culture is law. The new kingdoms created new law codes in Latin, with occasional Germanic words. These were Roman-influenced, and under strong church influence all law was increasingly standardized to accord with Christian philosophy, and old Roman law.

Germanic languages in western Europe no longer exist apart from the remaining West Germanic languages of England, the Frankish homelands near the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta, and the large area between the Rhine and Elbe. With the splitting off of this latter area within the Frankish empire, the first ever political entity corresponding loosely to modern "Germany" came into existence.

In Eastern Europe the once relatively developed periphery of the Roman world collapsed culturally and economically, and this can be seen in the Germanic-associated archaeological evidence: in the area of today's southern Poland and Ukraine the collapse occurred not long after 400, and by 700 Germanic material culture was entirely west of the Elbe in the area where the Romans had been active since Caesar's time, and the Franks were now active. East of the Elbe was to become mainly Slavic-speaking.

Outside of the Roman-influenced zone, Germanic-speaking Scandinavia was in the Vendel period and eventually entered the Viking Age, with expansion to Britain, Ireland and Iceland in the west and as far as Russia and Greece in the east. Swedish Vikings, known locally as the Rus', ventured deep into Russia, where they founded the political entities of Kievan Rus'. They defeated the Khazar Khaganate and became the dominant power in Eastern Europe. The dominant language of these communities came to be East Slavic. By 900 CE the Vikings also secured a foothold on Frankish soil along the Lower Seine River valley in what became known as Normandy. On the other hand, the Scandinavian countries were, starting with Denmark, under the influence of Germany to their south, and also the lands where they had colonies. Bit by bit they became Christian, and organized themselves into Frankish- and Catholic-influenced kingdoms.

Kingdom of Germany (Regnum Teutonicum) within the Holy Roman Empire, circa 1000 AD

Roman descriptions of early Germanic people and culture

:

Tacitus famously described the Germanic people as ethnically "unmixed", which had an influence on pre-1945 German racist nationalism. It was not necessarily meant to be purely positive :

For my own part, I agree with those who think that the tribes of Germany are free from all taint of inter-marriages with foreign nations, and that they appear as a distinct, unmixed race, like none but themselves. Hence, too, the same physical peculiarities throughout so vast a population. All have fierce blue eyes, red hair, huge frames, fit only for a sudden exertion. They are less able to bear laborious work. Heat and thirst they cannot in the least endure; to cold and hunger their climate and their soil inure them.

Modern scholars point out that one way of interpreting such remarks is that they are consistent with other comments by Tacitus indicating that the Germanic people lived very remotely, in unattractive countries, for example in the next part of the text :

Their country, though somewhat various in appearance, yet generally either bristles with forests or reeks with swamps; it is more rainy on the side of Gaul, bleaker on that of Noricum and Pannonia. It is productive of grain, but unfavourable to fruit-bearing trees; it is rich in flocks and herds, but these are for the most part undersized, and even the cattle have not their usual beauty or noble head.

Archaeological research has revealed that the early Germanic peoples were primarily agricultural, although husbandry and fishing were important sources of livelihood depending on the nature of their environment. They carried out extensive trade with their neighbours, notably exporting amber, slaves, mercenaries and animal hides, and importing weapons, metals, glassware and coins in return. They eventually came to excel at craftsmanship, particularly metalworking. In many cases, ancient Germanic smiths and other craftsmen produced products of higher quality than those of the Romans.

Before Tacitus, Julius Caesar described the Germani and their customs in his Commentarii de Bello Gallico, though in certain cases it is still a matter of debate if he refers to Northern Celtic peoples or clearly identified Germanic peoples. Caesar notes that the Gauls had earlier dominated and sent colonies into the lands of the Germans, but that the Gauls had since degenerated under the influence of Roman civilization, and now considered themselves inferior in military prowess.

[The Germani] have neither Druids to preside over sacred offices, nor do they pay great regard to sacrifices. They rank in the number of the gods those alone whom they behold, and by whose instrumentality they are obviously benefited, namely, the sun, fire, and the moon; they have not heard of the other deities even by report. Their whole life is occupied in hunting and in the pursuits of the military art; from childhood they devote themselves to fatigue and hardships. Those who have remained chaste for the longest time, receive the greatest commendation among their people; they think that by this the growth is promoted, by this the physical powers are increased and the sinews are strengthened. And to have had knowledge of a woman before the twentieth year they reckon among the most disgraceful acts; of which matter there is no concealment, because they bathe promiscuously in the rivers and [only] use skins or small cloaks of deer's hides, a large portion of the body being in consequence naked.

They do not pay much attention to agriculture, and a large portion of their food consists in milk, cheese, and flesh; nor has any one a fixed quantity of land or his own individual limits; but the magistrates and the leading men each year apportion to the groups and families, who have united together, as much land as, and in the place in which, they think proper, and the year after compel them to remove elsewhere.

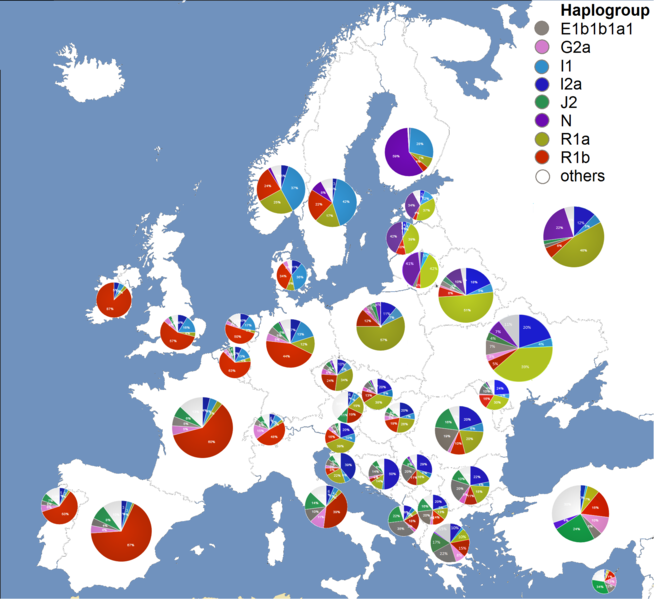

Genetics :

Percentage of major Y-DNA haplogroups in Europe; Haplogroup I1 represented by light blue In a 2013 book which reviewed studies up until then it was remarked that: "If and when scientists find ancient Y-DNA from men whom we can guess spoke Proto-Germanic, it is most likely to be a mixture of haplogroup I1, R1a1a, R1b-P312 and R1b-106". This was based purely upon those being the Y-DNA groups judged to be most commonly shared by speakers of Germanic languages today. However, as remarked in that book: "All of these are far older than Germanic languages and some are common among speakers of other languages too."

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |