| MONGOL

A Mongolian Buddhist Monk Languages

: Mongolian language

The Mongols (Mongolian: Mongolchuud) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia and to China's Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. They also live as minorities in other regions of China (e.g. Xinjiang), as well as in Russia. Mongolian people belonging to the Buryat and Kalmyk subgroups live predominantly in the Russian federal subjects of Buryatia and Kalmykia.

The Mongols are bound together by a common heritage and ethnic identity. Their indigenous dialects are collectively known as the Mongolian language. The ancestors of the modern-day Mongols are referred to as Proto-Mongols.

Definition

:

The designation "Mongol" briefly appeared in 8th century records of Tang China to describe a tribe of Shiwei. It resurfaced in the late 11th century during the Khitan-ruled Liao dynasty. After the fall of the Liao in 1125, the Khamag Mongols became a leading tribe on the Mongolian Plateau. However, their wars with the Jurchen-ruled Jin dynasty and the Tatar confederation had weakened them.

In the thirteenth century, the word Mongol grew into an umbrella term for a large group of Mongolic-speaking tribes united under the rule of Genghis Khan.

History

:

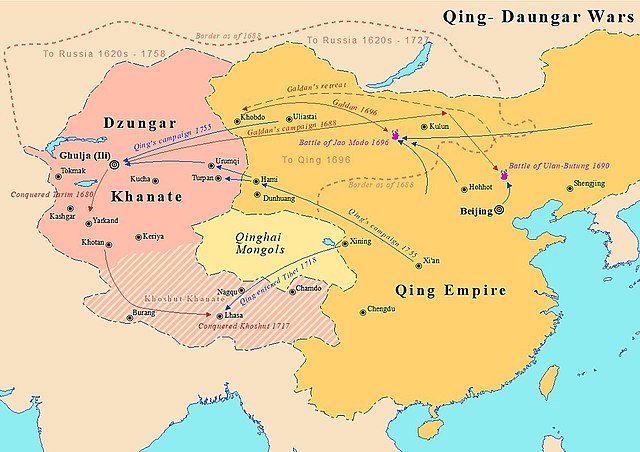

The Donghu, however, can be much more easily labeled proto-Mongol since the Chinese histories trace only Mongolic tribes and kingdoms (Xianbei and Wuhuan peoples) from them, although some historical texts claim a mixed Xiongnu-Donghu ancestry for some tribes (e.g. the Khitan).

Origin

:

The Xianbei formed part of the Donghu confederation, but had earlier times of independence, as evidenced by a mention in the Guoyu, which states that during the reign of King Cheng of Zhou (reigned 1042–1021 BCE) they came to participate at a meeting of Zhou subject-lords at Qiyang (now Qishan County) but were only allowed to perform the fire ceremony under the supervision of Chu since they were not vassals by covenant. The Xianbei chieftain was appointed joint guardian of the ritual torch along with Xiong Yi.

These early Xianbei came from the nearby Zhukaigou culture (2200–1500 BCE) in the Ordos Desert, where maternal DNA corresponds to the Mongol Daur people and the Tungusic Evenks. The Zhukaigou Xianbei (part of the Ordos culture of Inner Mongolia and northern Shaanxi) had trade relations with the Shang. In the late 2nd century, the Han dynasty scholar Fu Qian wrote in his commentary "Jixie" that "Shanrong and Beidi are ancestors of the present-day Xianbei". Again in Inner Mongolia another closely connected core Mongolic Xianbei region was the Upper Xiajiadian culture (1000–600 BCE) where the Donghu confederation was centered.

After the Donghu were defeated by Xiongnu king Modu Chanyu, the Xianbei and Wuhuan survived as the main remnants of the confederation. Tadun Khan of the Wuhuan (died 207 AD) was the ancestor of the proto-Mongolic Kumo Xi. The Wuhuan are of the direct Donghu royal line and the New Book of Tang says that in 209 BCE, Modu Chanyu defeated the Wuhuan instead of using the word Donghu. The Xianbei, however, were of the lateral Donghu line and had a somewhat separate identity, although they shared the same language with the Wuhuan. In 49 CE the Xianbei ruler Bianhe (Bayan Khan?) raided and defeated the Xiongnu, killing 2000, after having received generous gifts from Emperor Guangwu of Han. The Xianbei reached their peak under Tanshihuai Khan (reigned 156–181) who expanded the vast, but short lived, Xianbei state (93–234).

Three prominent groups split from the Xianbei state as recorded by the Chinese histories: the Rouran (claimed by some to be the Pannonian Avars), the Khitan people and the Shiwei (a subtribe called the "Shiwei Menggu" is held to be the origin of the Genghisid Mongols). Besides these three Xianbei groups, there were others such as the Murong, Duan and Tuoba. Their culture was nomadic, their religion shamanism or Buddhism and their military strength formidable. There is still no direct evidence that the Rouran spoke Mongolic languages, although most scholars agree that they were Proto-Mongolic. The Khitan, however, had two scripts of their own and many Mongolic words are found in their half-deciphered writings.

Geographically, the Tuoba Xianbei ruled the southern part of Inner Mongolia and northern China, the Rouran (Yujiulü Shelun was the first to use the title khagan in 402) ruled eastern Mongolia, western Mongolia, the northern part of Inner Mongolia and northern Mongolia, the Khitan were concentrated in eastern part of Inner Mongolia north of Korea and the Shiwei were located to the north of the Khitan. These tribes and kingdoms were soon overshadowed by the rise of the First Turkic Khaganate in 555, the Uyghur Khaganate in 745 and the Yenisei Kirghiz states in 840. The Tuoba were eventually absorbed into China. The Rouran fled west from the Göktürks and either disappeared into obscurity or, as some say, invaded Europe as the Avars under their Khan, Bayan I. Some Rouran under Tatar Khan migrated east, founding the Tatar confederation, who became part of the Shiwei. The Khitan, who were independent after their separation from the Kumo Xi (of Wuhuan origin) in 388, continued as a minor power in Manchuria until one of them, Ambagai (872–926), established the Liao dynasty (907–1125) as Emperor Taizu of Liao.

Era of the Mongol Empire and Northern Yuan :

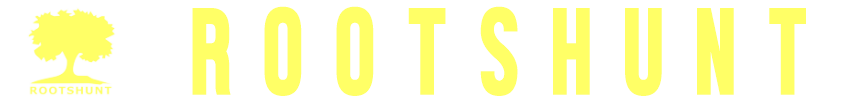

Asia in 500, showing the Rouran Khaganate and its neighbors, including the Northern Wei and the Tuyuhun Khanate, all of them were established by Proto-Mongols The destruction of Uyghur Khaganate by the Kirghiz resulted in the end of Turkic dominance in Mongolia. According to historians, Kirghiz were not interested in assimilating newly acquired lands; instead, they controlled local tribes through various manaps (tribal leader). The Khitans occupied the areas vacated by the Turkic Uyghurs bringing them under their control. The Yenisei Kirghiz state was centered on Khakassia and they were expelled from Mongolia by the Khitans in 924. Beginning in the 10th century, the Khitans, under the leadership of Abaoji, prevailed in several military campaigns against the Tang Dynasty's border guards, and the Xi, Shiwei and Jurchen nomadic groups.

The Khitan fled west after being defeated by the Jurchens (later known as Manchu) and founded the Qara Khitai (1125–1218) in eastern Kazakhstan. In 1218, Genghis Khan destroyed the Qara Khitai after which the Khitan passed into obscurity. With the expansion of the Mongol Empire, the Mongolic peoples settled over almost all Eurasia and carried on military campaigns from the Adriatic Sea to Indonesian Java island and from Japan to Palestine (Gaza). They simultaneously became Padishahs of Persia, Emperors of China, and Great Khans of Mongolia, and one became Sultan of Egypt (Al-Adil Kitbugha). The Mongolic peoples of the Golden Horde established themselves to govern Russia by 1240. By 1279, they conquered the Song dynasty and brought all of China under control of the Yuan dynasty.

Mongols using Chinese gunpowder bombs during the Mongol Invasions of Japan, 1281 With the breakup of the empire, the dispersed Mongolic peoples quickly adopted the mostly Turkic cultures surrounding them and were assimilated, forming parts of Azerbaijanis, Uzbeks, Karakalpaks, Tatars, Bashkirs, Turkmens, Uyghurs, Nogays, Kyrgyzs, Kazakhs, Caucasaus peoples, Iranian peoples and Moghuls; linguistic and cultural Persianization also began to be prominent in these territories. Some Mongols assimilated into the Yakuts after their migration to Northern Siberia and about 30% of Yakut words have Mongol origin. However, most of the Yuan Mongols returned to Mongolia in 1368, retaining their language and culture. There were 250,000 Mongols in Southern China and many Mongols were massacred by the rebel army. The survivors were trapped in southern china and eventually assimilated. The Dongxiangs, Bonans, Yugur and Monguor people were invaded by Chinese Ming dynasty.

After the fall of the Yuan dynasty in 1368, the Mongols continued to rule the Northern Yuan dynasty in Mongolia homeland. However, the Oirads began to challenge the Eastern Mongolic peoples under the Borjigin monarchs in the late 14th century and Mongolia was divided into two parts: Western Mongolia (Oirats) and Eastern Mongolia (Khalkha, Inner Mongols, Barga, Buryats). The earliest written references to the plough in Middle Mongolian language sources appear towards the end of the 14th c.

In 1434, Eastern Mongolian Taisun Khan's (1433–1452) prime minister Western Mongolian Togoon Taish reunited the Mongols after killing Eastern Mongolian another king Adai (Khorchin). Togoon died in 1439 and his son Esen Taish became prime minister. Esen carried out successful policy for Mongolian unification and independence. The Ming Empire attempted to invade Mongolia in the 14–16th centuries, however, the Ming Empire was defeated by the Oirat, Southern Mongol, Eastern Mongol and united Mongolian armies. Esen's 30,000 cavalries defeated 500,000 Chinese soldiers in 1449. Within eighteen months of his defeat of the titular Khan Taisun, in 1453, Esen himself took the title of Great Khan (1454–1455) of the Great Yuan.

The Khalkha emerged during the reign of Dayan Khan (1479–1543) as one of the six tumens of the Eastern Mongolic peoples. They quickly became the dominant Mongolic clan in Mongolia proper. He reunited the Mongols again. The Mongols voluntarily reunified during Eastern Mongolian Tümen Zasagt Khan rule (1558–1592) for the last time (the Mongol Empire united all Mongols before this).

Eastern Mongolia was divided into three parts in the 17th century: Outer Mongolia (Khalkha), Inner Mongolia (Inner Mongols) and the Buryat region in southern Siberia.

The last Mongol khagan was Ligdan in the early 17th century. He got into conflicts with the Manchus over the looting of Chinese cities, and managed to alienate most Mongol tribes. In 1618, Ligdan signed a treaty with the Ming dynasty to protect their northern border from the Manchus attack in exchange for thousands of taels of silver. By the 1620s, only the Chahars remained under his rule.

Qing-era

Mongols :

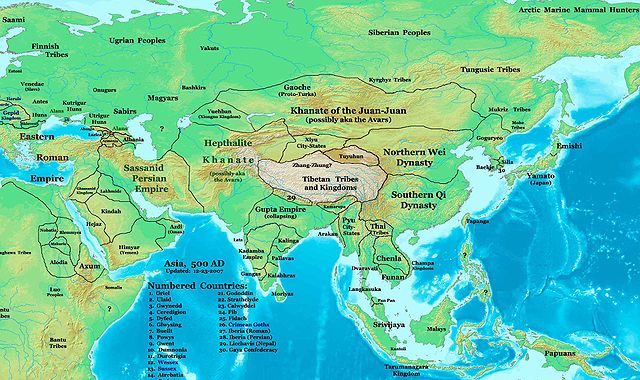

Western Mongolian Oirats and Eastern Mongolian Khalkhas vied for domination in Mongolia since the 15th century and this conflict weakened Mongolian strength. In 1688, Western Mongolian Dzungar Khanate's king Galdan Boshugtu attacked Khalkha after murder of his younger brother by Tusheet Khan Chakhundorj (main or Central Khalkha leader) and the Khalkha-Oirat War began. Galdan threatened to kill Chakhundorj and Zanabazar (Javzandamba Khutagt I, spiritual head of Khalkha) but they escaped to Sunud (Inner Mongolia). Many Khalkha nobles and folks fled to Inner Mongolia because of the war. Few Khalkhas fled to the Buryat region and Russia threatened to exterminate them if they did not submit, but many of them submitted to Galdan Boshugtu.

In 1683 Galdan's armies reached Tashkent and the Syr Darya and crushed two armies of the Kazakhs. After that Galdan subjugated the Black Khirgizs and ravaged the Fergana Valley. From 1685 Galdan's forces aggressively pushed the Kazakhs. While his general Rabtan took Taraz, and his main force forced the Kazakhs to migrate westwards. In 1687, he besieged the City of Turkistan. Under the leadership of Abul Khair Khan, the Kazakhs won major victories over the Dzungars at the Bulanty River in 1726, and at the Battle of Anrakay in 1729.

Map showing wars between Qing Dynasty and Dzungar Khanate The Khalkha eventually submitted to Qing rule in 1691 by Zanabazar's decision, thus bringing all of today's Mongolia under the rule of the Qing dynasty but Khalkha de facto remained under the rule of Galdan Boshugtu Khaan until 1696. The Mongol-Oirat's Code (a treaty of alliance) against foreign invasion between the Oirats and Khalkhas was signed in 1640, however, the Mongols could not unite against foreign invasions. Chakhundorj fought against Russian invasion of Outer Mongolia until 1688 and stopped Russian invasion of Khövsgöl Province. Zanabazar struggled to bring together the Oirats and Khalkhas before the war.

Galdan Boshugtu sent his army to "liberate" Inner Mongolia after defeating the Khalkha's army and called Inner Mongolian nobles to fight for Mongolian independence. Some Inner Mongolian nobles, Tibetans, Kumul Khanate and some Moghulistan's nobles supported his war against the Manchus, however, Inner Mongolian nobles did not battle against the Qing.

There were three khans in Khalkha and Zasagt Khan Shar (Western Khalkha leader) was Galdan's ally. Tsetsen Khan (Eastern Khalkha leader) did not engage in this conflict. While Galdan was fighting in Eastern Mongolia, his nephew Tseveenravdan seized the Dzungarian throne in 1689 and this event made Galdan impossible to fight against the Qing Empire. The Russian and Qing Empires supported his action because this coup weakened Western Mongolian strength. Galdan Boshugtu's army was defeated by the outnumbering Qing army in 1696 and he died in 1697. The Mongols who fled to the Buryat region and Inner Mongolia returned after the war. Some Khalkhas mixed with the Buryats.

A Mongol soldier called Ayusi from the high Qing era, by Giuseppe Castiglione, 1755 The Buryats fought against Russian invasion since the 1620s and thousands of Buryats were massacred. The Buryat region was formally annexed to Russia by treaties in 1689 and 1727, when the territories on both the sides of Lake Baikal were separated from Mongolia. In 1689 the Treaty of Nerchinsk established the northern border of Manchuria north of the present line. The Russians retained Trans-Baikalia between Lake Baikal and the Argun River north of Mongolia. The Treaty of Kyakhta (1727), along with the Treaty of Nerchinsk, regulated the relations between Imperial Russia and the Qing Empire until the mid-nineteenth century. It established the northern border of Mongolia. Oka Buryats revolted in 1767 and Russia completely conquered the Buryat region in the late 18th century. Russia and Qing were rival empires until the early 20th century, however, both empires carried out united policy against Central Asians.

The Battle of Oroi-Jalatu in 1755 between the Qing (that ruled China at the time) and Mongol Dzungar armies. The fall of the Dzungar Khanate The Qing Empire conquered Upper Mongolia or the Oirat's Khoshut Khanate in the 1720s and 80,000 people were killed. By that period, Upper Mongolian population reached 200,000. The Dzungar Khanate conquered by the Qing dynasty in 1755–1758 because of their leaders and military commanders conflicts. Some scholars estimate that about 80% of the Dzungar population were destroyed by a combination of warfare and disease during the Qing conquest of the Dzungar Khanate in 1755–1758. Mark Levene, a historian whose recent research interests focus on genocide, has stated that the extermination of the Dzungars was "arguably the eighteenth century genocide par excellence." The Dzungar population reached 600,000 in 1755.

About 200,000–250,000 Oirats migrated from Western Mongolia to Volga River in 1607 and established the Kalmyk Khanate.The Torghuts were led by their Tayishi, Höö Örlög. Russia was concerned about their attack but the Kalmyks became Russian ally and a treaty to protect Southern Russian border was signed between the Kalmyk Khanate and Russia.In 1724 the Kalmyks came under control of Russia. By the early 18th century, there were approximately 300–350,000 Kalmyks and 15,000,000 Russians. [citation needed] The Tsardom of Russia gradually chipped away at the autonomy of the Kalmyk Khanate. These policies, for instance, encouraged the establishment of Russian and German settlements on pastures the Kalmyks used to roam and feed their livestock.

In addition, the Tsarist government imposed a council on the Kalmyk Khan, thereby diluting his authority, while continuing to expect the Kalmyk Khan to provide cavalry units to fight on behalf of Russia. The Russian Orthodox church, by contrast, pressured Buddhist Kalmyks to adopt Orthodoxy.In January 1771, approximately 200,000 (170,000) Kalmyks began the migration from their pastures on the left bank of the Volga River to Dzungaria (Western Mongolia), through the territories of their Bashkir and Kazakh enemies. The last Kalmyk khan Ubashi led the migration to restore Mongolian independence. Ubashi Khan sent his 30,000 cavalries to the Russo-Turkish War in 1768–1769 to gain weapon before the migration. The Empress Catherine the Great ordered the Russian army, Bashkirs and Kazakhs to exterminate all migrants and the Empress abolished the Kalmyk Khanate.

The Kyrgyzs attacked them near Balkhash Lake. About 100,000–150,000 Kalmyks who settled on the west bank of the Volga River could not cross the river because the river did not freeze in the winter of 1771 and Catherine the Great executed influential nobles of them. After seven months of travel, only one-third (66,073) of the original group reached Dzungaria (Balkhash Lake, western border of the Qing Empire). The Qing Empire transmigrated the Kalmyks to five different areas to prevent their revolt and influential leaders of the Kalmyks died soon (killed by the Manchus). Russia states that Buryatia voluntarily merged with Russia in 1659 due to Mongolian oppression and the Kalmyks voluntarily accepted Russian rule in 1609 but only Georgia voluntarily accepted Russian rule.

In the early 20th century, the late Qing government encouraged Han Chinese colonization of Mongolian lands under the name of "New Policies" or "New Administration" (xinzheng). As a result, some Mongol leaders (especially those of Outer Mongolia) decided to seek Mongolian independence. After the Xinhai Revolution, the Mongolian Revolution on 30 November 1911 in Outer Mongolia ended over 200-year rule of the Qing dynasty.

Post-Qing era :

Buddhist lama in Mongolia near Ulaanbaatar, probably Sodnomyn Damdinbazar With the independence of Outer Mongolia, the Mongolian army controlled Khalkha and Khovd regions (modern day Uvs, Khovd, and Bayan-Ölgii provinces), but Northern Xinjiang (the Altai and Ili regions of the Qing Empire), Upper Mongolia, Barga and Inner Mongolia came under control of the newly formed Republic of China. On February 2, 1913 the Bogd Khanate of Mongolia sent Mongolian cavalries to "liberate" Inner Mongolia from China. Russia refused to sell weapons to the Bogd Khanate, and the Russian czar, Nicholas II, referred to it as "Mongolian imperialism". Additionally, the United Kingdom urged Russia to abolish Mongolian independence as it was concerned that "if Mongolians gain independence, then Central Asians will revolt". 10,000 Khalkha and Inner Mongolian cavalries (about 3,500 Inner Mongols) defeated 70,000 Chinese soldiers and controlled almost all of Inner Mongolia; however, the Mongolian army retreated due to lack of weapons in 1914.

400 Mongol soldiers and 3,795 Chinese soldiers died in this war. The Khalkhas, Khovd Oirats, Buryats, Dzungarian Oirats, Upper Mongols, Barga Mongols, most Inner Mongolian and some Tuvan leaders sent statements to support Bogd Khan's call of Mongolian reunification. In reality however, most of them were too prudent or irresolute to attempt joining the Bogd Khan regime. Russia encouraged Mongolia to become an autonomous region of China in 1914. Mongolia lost Barga, Dzungaria, Tuva, Upper Mongolia and Inner Mongolia in the 1915 Treaty of Kyakhta.

In October 1919, the Republic of China occupied Mongolia after the suspicious deaths of Mongolian patriotic nobles. On 3 February 1921 the White Russian army—led by Baron Ungern and mainly consisting of Mongolian volunteer cavalries, and Buryat and Tatar cossacks—liberated the Mongolian capital. Baron Ungern's purpose was to find allies to defeat the Soviet Union. The Statement of Reunification of Mongolia was adopted by Mongolian revolutionist leaders in 1921. The Soviet, however, considered Mongolia to be Chinese territory in 1924 during secret meeting with the Republic of China. However, the Soviets officially recognized Mongolian independence in 1945 but carried out various policies (political, economic and cultural) against Mongolia until its fall in 1991 to prevent Pan-Mongolism and other irredentist movements.

On 10 April 1932 Mongolians revolted against the government's new policy and Soviets. The government and Soviet soldiers defeated the rebels in October.

The Buryats started to migrate to Mongolia in the 1900s due to Russian oppression. Joseph Stalin's regime stopped the migration in 1930 and started a campaign of ethnic cleansing against newcomers and Mongolians. During the Stalinist repressions in Mongolia almost all adult Buryat men and 22–33,000 Mongols (3–5% of the total population; common citizens, monks, Pan-Mongolists, nationalists, patriots, hundreds military officers, nobles, intellectuals and elite people) were shot dead under Soviet orders. Some authors also offer much higher estimates, up to 100,000 victims. Around the late 1930s the Mongolian People's Republic had an overall population of about 700,000 to 900,000 people. By 1939, Soviet said "We repressed too many people, the population of Mongolia is only hundred thousands". Proportion of victims in relation to the population of the country is much higher than the corresponding figures of the Great Purge in the Soviet Union.

Khorloogiin Choibalsan, leader of the Mongolian People's Republic (left), and Georgy Zhukov consult during the Battle of Khalkhin Gol against Japanese troops, 1939 The Manchukuo (1932–1945), puppet state of the Empire of Japan (1868–1947) invaded Barga and some part of Inner Mongolia with Japanese help. The Mongolian army advanced to the Great Wall of China during the Soviet–Japanese War of 1945 (Mongolian name: Liberation War of 1945). Japan forced Inner Mongolian and Barga people to fight against Mongolians but they surrendered to Mongolians and started to fight against their Japanese and Manchu allies. Marshal Khorloogiin Choibalsan called Inner Mongolians and Xinjiang Oirats to migrate to Mongolia during the war but the Soviet Army blocked Inner Mongolian migrants way. It was a part of Pan-Mongolian plan and few Oirats and Inner Mongols (Huuchids, Bargas, Tümeds, about 800 Uzemchins) arrived. Inner Mongolian leaders carried out active policy to merge Inner Mongolia with Mongolia since 1911. They founded the Inner Mongolian Army in 1929 but the Inner Mongolian Army disbanded after ending World War II. The Japanese Empire supported Pan-Mongolism since the 1910s but there have never been active relations between Mongolia and Imperial Japan due to Russian resistance. Inner Mongolian nominally independent Mengjiang state (1936–1945) was established with support of Japan in 1936 also some Buryat and Inner Mongol nobles founded Pan-Mongolist government with support of Japan in 1919.

World War II Zaisan Memorial, Ulaan Baatar, from the People's Republic of Mongolia era The Inner Mongols established the short-lived Republic of Inner Mongolia in 1945.

Another part of Choibalsan's plan was to merge Inner Mongolia and Dzungaria with Mongolia. By 1945, Chinese communist leader Mao Zedong requested the Soviets to stop Pan-Mongolism because China lost its control over Inner Mongolia and without Inner Mongolian support the Communists were unable to defeat Japan and Kuomintang.

Mongolia and Soviet-supported Xinjiang Uyghurs and Kazakhs' separatist movement in the 1930–1940s. By 1945, Soviet refused to support them after its alliance with the Communist Party of China and Mongolia interrupted its relations with the separatists under pressure. Xinjiang Oirat's groups operated together the Turkic peoples but the Oirats did not have the leading role due to their small population. Basmachis or Turkic and Tajik fought to liberate Central Asia (Soviet Central Asia) until 1942.

On February 2, 1913 the Treaty of friendship and alliance between the Government of Mongolia and Tibet was signed. Mongolian agents and Bogd Khan disrupted Soviet secret operations in Tibet to change its regime in the 1920s.

On October 27, 1961, the United Nations recognized Mongolian independence and granted the nation full membership in the organization.

The Tsardom of Russia, Russian Empire, Soviet Union, capitalist and communist China performed many genocide actions against the Mongols (assimilate, reduce the population, extinguish the language, culture, tradition, history, religion and ethnic identity). Peter the Great said: "The headwaters of the Yenisei River must be Russian land". Russian Empire sent the Kalmyks and Buryats to war to reduce the populations (World War I and other wars). Soviet scientists attempted to convince the Kalmyks and Buryats that they're not the Mongols during the 20th century (demongolization policy). 35,000 Buryats were killed during the rebellion of 1927 and around one-third of Buryat population in Russia died in the 1900s–1950s. 10,000 Buryats of the Buryat-Mongol Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic were massacred by Stalin's order in the 1930s. In 1919 the Buryats established a small theocratic Balagad state in Kizhinginsky District of Russia and the Buryat's state fell in 1926. In 1958, the name "Mongol" was removed from the name of the Buryat-Mongol Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic.

On 22 January 1922 Mongolia proposed to migrate the Kalmyks during the Kalmykian Famine but bolshevik Russia refused.71–72,000 (93,000?; around half of the population) Kalmyks died during the Russian famine of 1921–22. The Kalmyks revolted against Soviet Union in 1926, 1930 and 1942–1943 (see Kalmykian Cavalry Corps). In 1913, Nicholas II, tsar of Russia, said: "We need to prevent from Volga Tatars. But the Kalmyks are more dangerous than them because they are the Mongols so send them to war to reduce the population". On 23 April 1923 Joseph Stalin, communist leader of Russia, said: "We are carrying out wrong policy on the Kalmyks who related to the Mongols.Our policy is too peaceful". In March 1927, Soviet deported 20,000 Kalmyks to Siberia, tundra and Karelia.The Kalmyks founded sovereign Republic of Oirat-Kalmyk on 22 March 1930.The Oirat's state had a small army and 200 Kalmyk soldiers defeated 1,700 Soviet soldiers in Durvud province of Kalmykia but the Oirat's state destroyed by the Soviet Army in 1930. Kalmykian nationalists and Pan-Mongolists attempted to migrate Kalmyks to Mongolia in the 1920s. Mongolia suggested to migrate the Soviet Union's Mongols to Mongolia in the 1920s but Russia refused the suggest.

Stalin deported all Kalmyks to Siberia in 1943 and around half of (97–98,000) Kalmyk people deported to Siberia died before being allowed to return home in 1957. The government of the Soviet Union forbade teaching Kalmyk language during the deportation. The Kalmyks' main purpose was to migrate to Mongolia and many Kalmyks joined the German Army.Marshal Khorloogiin Choibalsan attempted to migrate the deportees to Mongolia and he met with them in Siberia during his visit to Russia. Under the Law of the Russian Federation of April 26, 1991 "On Rehabilitation of Exiled Peoples" repressions against Kalmyks and other peoples were qualified as an act of genocide.

Mongolian President Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj (right) After the end of World War II, the Chinese Civil War resumed between the Chinese Nationalists (Kuomintang), led by Chiang Kai-shek, and the Chinese Communist Party, led by Mao Zedong. In December 1949, Chiang evacuated his government to Taiwan. Hundred thousands Inner Mongols were massacred during the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s and China forbade Mongol traditions, celebrations and the teaching of Mongolic languages during the revolution. In Inner Mongolia, some 790,000 people were persecuted. Approximately 1,000,000 Inner Mongols were killed during the 20th century. [citation needed] In 1960 Chinese newspaper wrote that "Han Chinese ethnic identity must be Chinese minorities ethnic identity". [citation needed] China-Mongolia relations were tense from the 1960s to the 1980s as a result of Sino-Soviet split, and there were several border conflicts during the period. Cross-border movement of Mongols was therefore hindered.

On 3 October 2002 the Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced that Taiwan recognizes Mongolia as an independent country, although no legislative actions were taken to address concerns over its constitutional claims to Mongolia. Offices established to support Taipei's claims over Outer Mongolia, such as the Mongolian and Tibetan Affairs Commission, lie dormant.

Agin-Buryat Okrug and Ust-Orda Buryat Okrugs merged with Irkutsk Oblast and Chita Oblast in 2008 despite Buryats' resistance. Small scale protests occurred in Inner Mongolia in 2011. The Inner Mongolian People's Party is a member of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization and its leaders are attempting to establish sovereign state or merge Inner Mongolia with Mongolia.

A Mongolic Ger Language :

Mongolian is the official national language of Mongolia, where it is spoken by nearly 2.8 million people (2010 estimate), and the official provincial language of China's Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, where there are at least 4.1 million ethnic Mongols. Across the whole of China, the language is spoken by roughly half of the country's 5.8 million ethnic Mongols (2005 estimate). However, the exact number of Mongolian speakers in China is unknown, as there is no data available on the language proficiency of that country's citizens. The use of Mongolian in China, specifically in Inner Mongolia, has witnessed periods of decline and revival over the last few hundred years. The language experienced a decline during the late Qing period, a revival between 1947 and 1965, a second decline between 1966 and 1976, a second revival between 1977 and 1992, and a third decline between 1995 and 2012. However, in spite of the decline of the Mongolian language in some of Inner Mongolia's urban areas and educational spheres, the ethnic identity of the urbanized Chinese-speaking Mongols is most likely going to survive due to the presence of urban ethnic communities. The multilingual situation in Inner Mongolia does not appear to obstruct efforts by ethnic Mongols to preserve their language. Although an unknown number of Mongols in China, such as the Tumets, may have completely or partially lost the ability to speak their language, they are still registered as ethnic Mongols and continue to identify themselves as ethnic Mongols. The children of inter-ethnic Mongol-Chinese marriages also claim to be and are registered as ethnic Mongols.

The specific origin of the Mongolic languages and associated tribes is unclear. Linguists have traditionally proposed a link to the Tungusic and Turkic language families, included alongside Mongolic in the broader group of Altaic languages, though this remains controversial. Today the Mongolian peoples speak at least one of several Mongolic languages including Mongolian, Buryat, Oirat, Dongxiang, Tu, Bonan, Hazaragi, and Aimaq. Additionally, many Mongols speak either Russian or Mandarin Chinese as languages of inter-ethnic communication.

Religion :

Buddhist temple in Buryatia, Russia The original religion of the Mongolic peoples was Shamanism. The Xianbei came in contact with Confucianism and Daoism but eventually adopted Buddhism. However, the Xianbeis in Mongolia and Rourans followed a form of Shamanism. In the 5th century the Buddhist monk Dharmapriya was proclaimed State Teacher of the Rouran Khaganate and given 3000 families and some Rouran nobles became Buddhists. In 511 the Rouran Douluofubadoufa Khan sent Hong Xuan to the Tuoba court with a pearl-encrusted statue of the Buddh as a gift. The Tuoba Xianbei and Khitans were mostly Buddhists, although they still retained their original Shamanism. The Tuoba had a "sacrificial castle" to the west of their capital where ceremonies to spirits took place. Wooden statues of the spirits were erected on top of this sacrificial castle. One ritual involved seven princes with milk offerings who ascended the stairs with 20 female shamans and offered prayers, sprinkling the statues with the sacred milk. The Khitan had their holiest shrine on Mount Muye where portraits of their earliest ancestor Qishou Khagan, his wife Kedun and eight sons were kept in two temples.

Mongolic peoples were also exposed to Zoroastrianism, Manicheism, Nestorianism, Eastern Orthodoxy and Islam from the west. The Mongolic peoples, in particular the Borjigin, had their holiest shrine on Mount Burkhan Khaldun where their ancestor Börte Chono (Blue Wolf) and Goo Maral (Beautiful Doe) had given birth to them. Genghis Khan usually fasted, prayed and meditated on this mountain before his campaigns. As a young man he had thanked the mountain for saving his life and prayed at the foot of the mountain sprinkling offerings and bowing nine times to the east with his belt around his neck and his hat held at his chest. Genghis Khan kept a close watch on the Mongolic supreme shaman Kokochu Teb who sometimes conflicted with his authority. Later the imperial cult of Genghis Khan (centered on the eight white gers and nine white banners in Ordos) grew into a highly organized indigenous religion with scriptures in the Mongolian script. Indigenous moral precepts of the Mongolic peoples were enshrined in oral wisdom sayings (now collected in several volumes), the anda (blood-brother) system and ancient texts such as the Chinggis-un Bilig (Wisdom of Genghis) and Oyun Tulkhuur (Key of Intelligence). These moral precepts were expressed in poetic form and mainly involved truthfulness, fidelity, help in hardship, unity, self-control, fortitude, veneration of nature, veneration of the state and veneration of parents.

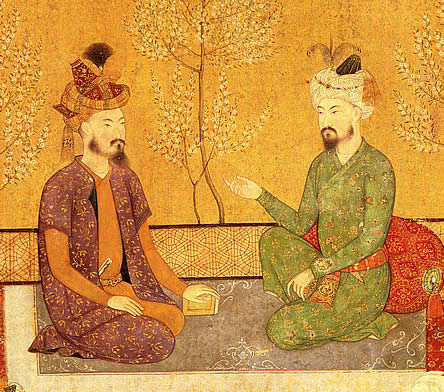

Timur of Mongolic origin himself had converted almost all the Borjigin leaders to Islam In 1254 Möngke Khan organized a formal religious debate (in which William of Rubruck took part) between Christians, Muslims and Buddhists in Karakorum, a cosmopolitan city of many religions. The Mongolic Empire was known for its religious tolerance, but had a special leaning towards Buddhism and was sympathetic towards Christianity while still worshipping Tengri. The Mongolic leader Abaqa Khan sent a delegation of 13–16 to the Second Council of Lyon (1274), which created a great stir, particularly when their leader 'Zaganus' underwent a public baptism. A joint crusade was announced in line with the Franco-Mongol alliance but did not materialize because Pope Gregory X died in 1276. Yahballaha III (1245–1317) and Rabban Bar Sauma (c. 1220–1294) were famous Mongolic Nestorian Christians. The Keraites in central Mongolia were Christian.

In Istanbul the Church of Saint Mary of the Mongols stands as a reminder of the Byzantine-Mongol alliance. The western Khanates, however, eventually adopted Islam (under Berke and Ghazan) and the Turkic languages (because of its commercial importance), although allegiance to the Great Khan and limited use of the Mongolic languages can be seen even in the 1330s. In 1521 the first Mughal emperor Babur took part in a military banner milk-sprinkling ceremony in the Chagatai Khanate where the Mongolian language was still used. Al-Adil Kitbugha (reigned 1294-1296), a Mongol Sultan of Egypt, and the half-Mongol An-Nasir Muhammad (reigned till 1341) built the Madrassa of Al-Nasir Muhammad in Cairo, Egypt. An-Nasir's Mongol mother was Ashlun bint Shaktay. The Mongolic nobility during the Yuan dynasty studied Confucianism, built Confucian temples (including Beijing Confucius Temple) and translated Confucian works into Mongolic but mainly followed the Sakya school of Tibetan Buddhism under Phags-pa Lama. The general populace still practised Shamanism. Dongxiang and Bonan Mongols adopted Islam, as did Moghol-speaking peoples in Afghanistan. In the 1576 the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism became the state religion of the Mongolia. The Red Hat school of Tibetan Buddhism coexisted with the Gelug Yellow Hat school which was founded by the half-Mongol Je Tsongkhapa (1357-1419). Shamanism was absorbed into the state religion while being marginalized in its purer forms, later only surviving in far northern Mongolia.

Monks were some of the leading intellectuals in Mongolia, responsible for much of the literature and art of the pre-modern period. Many Buddhist philosophical works lost in Tibet and elsewhere are preserved in older and purer form in Mongolian ancient texts (e.g. the Mongol Kanjur). Zanabazar (1635–1723), Zaya Pandita (1599–1662) and Danzanravjaa (1803–1856) are among the most famous Mongol holy men. The 4th Dalai Lama Yonten Gyatso (1589–1617), a Mongol himself, is recognized as the only non-Tibetan Dalai Lama although the current 14th Dalai Lama is of Mongolic Monguor extraction. The name is a combination of the Mongolian word dalai meaning "ocean" and the Tibetan word (bla-ma) meaning "guru, teacher, mentor".

Many Buryats became Orthodox Christians due to the Russian expansion. During the socialist period religion was officially banned, although it was practiced in clandestine circles. Today, a sizable proportion of Mongolic peoples are atheist or agnostic. In the most recent census in Mongolia, almost forty percent of the population reported as being atheist, while the majority religion was Tibetan Buddhism, with 53%. Having survived suppression by the Communists, Buddhism among the Eastern, Northern, Southern and Western Mongols is today primarily of the Gelugpa (Yellow Hat sect) school of Tibetan Buddhism. There is a strong shamanistic influence in the Gelugpa sect among the Mongols.

The Mughal Emperor Babur and his heir Humayun, The word Mughal, is derived from the Persian word for Mongol

Military :

Kinship and family life :

The traditional Mongol family was patriarchal, patrilineal and patrilocal. Wives were brought for each of the sons, while daughters were married off to other clans. Wife-taking clans stood in a relation of inferiority to wife-giving clans. Thus wife-giving clans were considered "elder" or "bigger" in relation to wife-taking clans, who were considered "younger" or "smaller". This distinction, symbolized in terms of "elder" and "younger" or "bigger" and "smaller", was carried into the clan and family as well, and all members of a lineage were terminologically distinguished by generation and age, with senior superior to junior.

In the traditional Mongolian family, each son received a part of the family herd as he married, with the elder son receiving more than the younger son. The youngest son would remain in the parental tent caring for his parents, and after their death he would inherit the parental tent in addition to his own part of the herd. This inheritance system was mandated by law codes such as the Yassa, created by Genghis Khan. Likewise, each son inherited a part of the family's camping lands and pastures, with the elder son receiving more than the younger son. The eldest son inherited the farthest camping lands and pastures, and each son in turn inherited camping lands and pastures closer to the family tent until the youngest son inherited the camping lands and pastures immediately surrounding the family tent. Family units would often remain near each other and in close cooperation, though extended families would inevitably break up after a few generations. It is probable that the Yasa simply put into written law the principles of customary law.

It is apparent that in many cases, for example in family instructions, the yasa tacitly accepted the principles of customary law and avoided any interference with them. For example, Riasanovsky said that killing the man or the woman in case of adultery is a good illustration. Yasa permitted the institutions of polygamy and concubinage so characteristic of southerly nomadic peoples. Children born of concubines were legitimate. Seniority of children derived their status from their mother. Eldest son received more than the youngest after the death of father. But the latter inherited the household of the father. Children of concubines also received a share in the inheritance, in accordance with the instructions of their father (or with custom.)

—

Nilgün Dalkesen, Gender roles and women's status in Central

Asia and Anatolia between the thirteenth and sixteenth centuries.

The Mongol kinship is one of a particular patrilineal type classed as Omaha, in which relatives are grouped together under separate terms that crosscut generations, age, and even sexual difference. Thus, oe uses different terms for a man's father's sister's children, his sister's children, and his daughter's children. A further attribute is strict terminological differentiation of siblings according to seniority.

The division of Mongolian society into senior elite lineages and subordinate junior lineages was waning by the twentieth century. During the 1920s, the Communist regime was established. The remnants of the Mongolian aristocracy fought alongside the Japanese and against Chinese, Soviets and Communist Mongols during World War II, but were defeated.

The anthropologist Herbert Harold Vreeland visited three Mongol communities in 1920 and published a highly detailed book with the results of his fieldwork, Mongol community and kinship structure.

Royal

family :

Dayan Khan's ancestry is as follows. His father was Bayanmunkh Jonon (1448-1479) the son of Kharkhutsag Taij (?-1453), the son of Agbarjin Khan (1423-1454), the son of Ajai Taij (1399-1438), the son or younger brother of Elbeg Nigülesügchi Khan (1361-1399), the son of Uskhal Khan (1342-1388), the younger brother of Biligtü Khan (1340-1370) and the son of Toghon Temur Khan (1320-1370), the son of Khutughtu Khan (1300-1329), the son of Külüg Khan (1281-1311), the son of Darmabala (1264-1292), the son of Crown Prince Zhenjin (1243-1286), the son of Kublai Khan (1215-1294), the son of Tolui (1191-1232), the son of Genghis Khan (1162-1227). Okada (1994) noted that according to the Korean Veritable Records Taisun Khan, the brother of Agbarjin Khan, sent a Mongolian letter to Korea on May 9, 1442 where he named Kublai Khan as his ancestor. This, along with the direct Mongol account of the Erdeniin Tobchi as well as indirect indications from three different Mongolian chronicles noted in Okada, establishes the Kublaid descent of Elbeg Nigülesügchi Khan. Buyandelger (2000) noted that the year of birth of Elbeg Nigülesügchi Khan as well as the meaning of his name is the same as that of Maidarabala the son of Biligtü Khan's secondary consort Empress Kim (daughter of Kim Yunjang). Further noting that Maidarabala was sent back to Mongolia in 1374 after being held hostage in Beiping (Beijing) for 3 years Buyandelger identified Maidarabala with Elbeg Nigülesügchi Khan. This does not change the Kublaid descent of Elbeg Nigülesügchi Khan and only changes his paternity from Uskhal Khan to his brother Biligtü Khan.

The Khongirad was the main consort clan of the Borjigin and provided numerous Empresses and consorts. There were five minor non-Khonggirad inputs from the maternal side which passed on to the Dayan Khanid aristocracy of Mongolia and Inner Mongolia. The first was the Keraite lineage added through Kublai Khan's mother Sorghaghtani Beki which linked the Borjigin to the Nestorian Christian tribe of Cyriacus Buyruk Khan. The second was the Turkic Karluk lineage added through Toghon Temur Khan's mother Mailaiti which linked the Borjigin to Bilge Kul Qadir Khan (840-893) of the Kara-Khanid Khanate and ultimately to the Lion-Karluks as well as the Ashina tribe of the 6th century Göktürks. The third was the Korean lineage added through Biligtü Khan's mother Empress Gi (1315-370) which linked the Borjigin to the Haengju Gi clan and ultimately to King Jun of Gojeoson (262-184 BC) and possibly even further to King Tang of Shang (1675-1646 BC) through Jizi. The fourth was the Esen Taishi lineage added through Bayanmunkh Jonon's mother Tsetseg Khatan which linked the Borjigin more firmly to the Oirats. The fifth was the Aisin Gioro lineage added during the Qing Dynasty.

The Dayan Khanid aristocracy still held power during the Bogd Khanate of Mongolia (1911-1919) and the Constitutional Monarchy period (1921-1924). They were accused of collaboration with the Japanese and executed in 1937 while their counterparts in Inner Mongolia were severely persecuted during the Cultural Revolution. Ancestral shrines of Genghis Khan were destroyed by the Red Guards during the 1960s and the Horse-Tail Banner of Genghis Khan disappeared. The Rinchen family in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia is a Dayan Khanid branch from Buryatia. Members of this family include the scholar Byambyn Rinchen (1905-1977), geologist Rinchen Barsbold (1935- ), diplomat Ganibal Jagvaral and Amartuvshin Ganibal (1974- ) the President of XacBank. There are many other families with aristocratic ancestry in Mongolia and it is often noted that most of the common populace already has some share of Genghisid ancestry. Mongolia, however, has remained a republic since 1924 and there has been no discussion of introducing a constitutional monarchy.

Historical population :

Geographic distribution :

This map shows the boundary of the 13th-century Mongol Empire and location of today's Mongols in modern Mongolia, Russia and China Today, the majority of Mongols live in the modern state of Mongolia, China (mainly Inner Mongolia and Xinjiang), Russia, Kyrgyzstan and Afghanistan.

The differentiation between tribes and peoples (ethnic groups) is handled differently depending on the country. The Tumed, Chahar, Ordos, Barga, Altai Uriankhai, Buryats, Dörböd (Dörvöd, Dörbed), Torguud, Dariganga, Üzemchin (or Üzümchin), Bayads, Khoton, Myangad (Mingad), Eljigin, Zakhchin, Darkhad, and Olots (or Öölds or Ölöts) are all considered as tribes of the Mongols.

Subgroups

:

The Buryats are mainly concentrated in their homeland, the Buryat Republic, a federal subject of Russia. They are the major northern subgroup of the Mongols. The Barga Mongols are mainly concentrated in Inner Mongolia, China, along with the Buryats and Hamnigan. The Southern or Inner Mongols mainly are concentrated in Inner Mongolia, China. They comprise the Abaga Mongols, Abaganar, Aohan, Asud, Baarins, Chahar, Durved, Gorlos, Kharchin, Hishigten, Khorchin, Huuchid, Jalaid, Jaruud, Muumyangan, Naiman (Southern Mongols), Onnigud, Ordos, Sunud, Tümed, Urad, and Uzemchin.

The Western Mongols or Oirats are mainly concentrated in Western Mongolia :

•

184,000 Kalmyks

(2010) — Kalmykia, Russia

•

Kalmyks —

Baatud, Buzava, Choros, Durvud, Khoid, Olots, Torghut.

Mongol women in traditional dress In modern-day Mongolia, Mongols make up approximately 95% of the population, with the largest ethnic group being Khalkha Mongols, followed by Buryats, both belonging to the Eastern Mongolic peoples. They are followed by Oirats, who belong to the Western Mongolic peoples.

Mongolian ethnic groups: Baarin, Baatud, Barga, Bayad, Buryat, Selenge Chahar, Chantuu, Darkhad, Dariganga Dörbet Oirat, Eljigin, Khalkha, Hamnigan, Kharchin, Khoid, Khorchin, Hotogoid, Khoton, Huuchid, Myangad, Olots, Sartuul, Torgut, Tümed, Üzemchin, Zakhchin.

China :

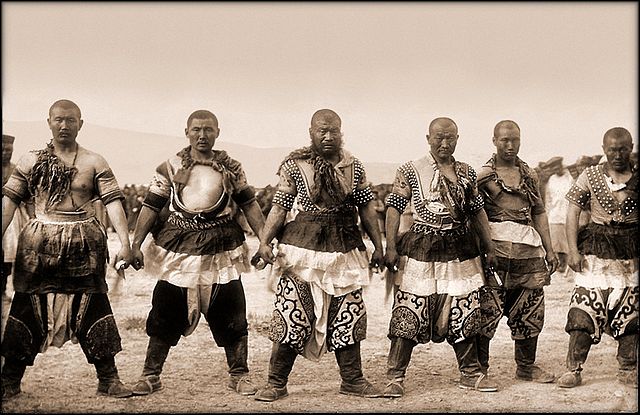

Strong Mongol men at August games. Photo by Wm. Purdom, 1909 The 2010 census of the People's Republic of China counted more than 7 million people of various Mongolic groups. The 1992 census of China counted only 3.6 million ethnic Mongols. [citation needed] The 2010 census counted roughly 5.8 million ethnic Mongols, 621,500 Dongxiangs, 289,565 Mongours, 132,000 Daurs, 20,074 Baoans, and 14,370 Yugurs. [citation needed] Most of them live in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, followed by Liaoning. Small numbers can also be found in provinces near those two.

There were 669,972 Mongols in Liaoning in 2011, making up 11.52% of Mongols in China. The closest Mongol area to the sea is the Dabao Mongol Ethnic Township in Fengcheng, Liaoning. With 8,460 Mongols (37.4% of the township population) [citation needed] it is located 40 km (25 mi) from the North Korean border and 65 km (40 mi)from Korea Bay of the Yellow Sea. Another contender for closest Mongol area to the sea would be Erdaowanzi Mongol Ethnic Township in Jianchang County, Liaoning. With 5,011 Mongols (20.7% of the township population) [citation needed] it is located around 65 km (40 mi)from the Bohai Sea.

Other peoples speaking Mongolic languages are the Daur, Sogwo Arig, Monguor people, Dongxiangs, Bonans, Sichuan Mongols and eastern part of the Yugur people. Those do not officially count as part of the Mongol ethnicity, but are recognized as ethnic groups of their own. The Mongols lost their contact with the Mongours, Bonan, Dongxiangs, Yunnan Mongols since the fall of the Yuan dynasty. Mongolian scientists and journalists met with the Dongxiangs and Yunnan Mongols in the 2000s.[citation needed]

Inner Mongolia : Southern Mongols, Barga, Buryat, Dörbet Oirat, Khalkha, Dzungar people, Eznee Torgut.

Xinjiang province : Altai Uriankhai, Chahar, Khoshut, Olots, Torghut, Zakhchin.

Qinghai province : Upper Mongols: Choros, Khalkha Mongols, Khoshut, Torghut.

Russia

:

Elsewhere

:

Gallery :

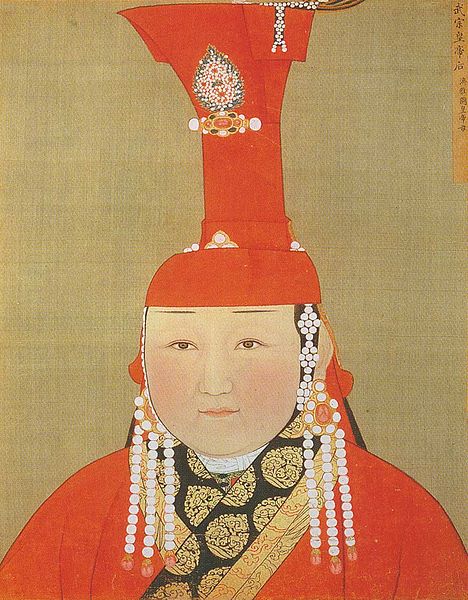

Mongol Empress Zayaat (Jiyatu), wife of Kulug Khan (1281 – 1311)

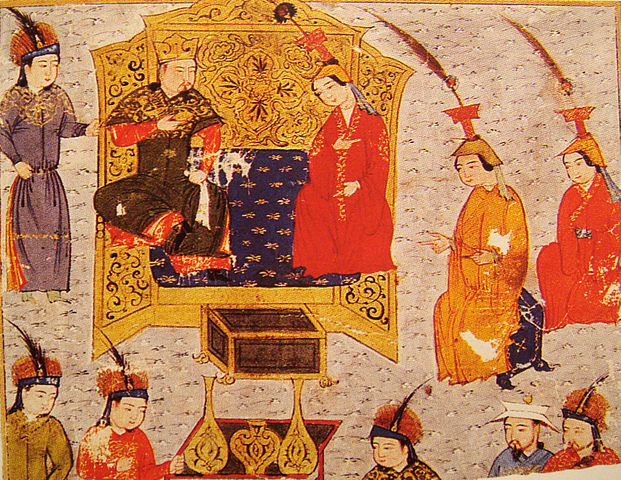

Genghis' son Tolui with Queen Sorgaqtani

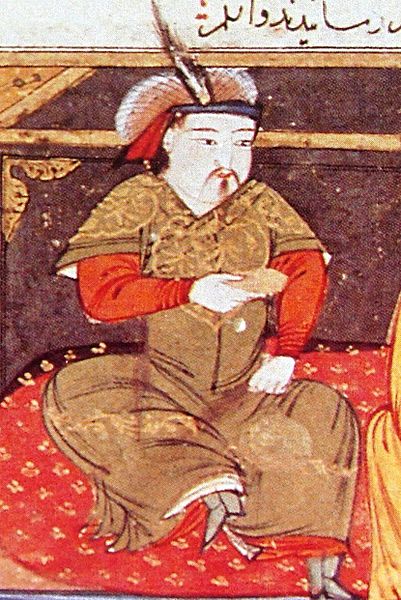

Hulegu Khan, ruler of the Ilkhanate

13th century Ilkhanid Mongol archer

Mongol soldiers by Rashid al-Din in 1305

Kalmyk Mongol girl Annushka (painted in 1767)

A 20th-century Mongol Khan, Navaanneren

The 4th Dalai Lama Yonten Gyatso

Dolgorsürengiin Dagvadorj became the first Mongol to reach sumo's highest rank

Mongol women archers during Naadam festival

A Mongol musician

A Mongol Wrangler

Buryat Mongol shaman

Kalmyks, 19th century

Mongol girl performing Bayad dance

Buryat Mongols (painted in 1840)

Daur Mongol Empress Wanrong (1906 – 1946), also had Borjigin blood on maternal side

Buryat Mongol boy during shamanic rite

Concubine Wenxiu was Puyi's consort Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

_(16769576222).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)