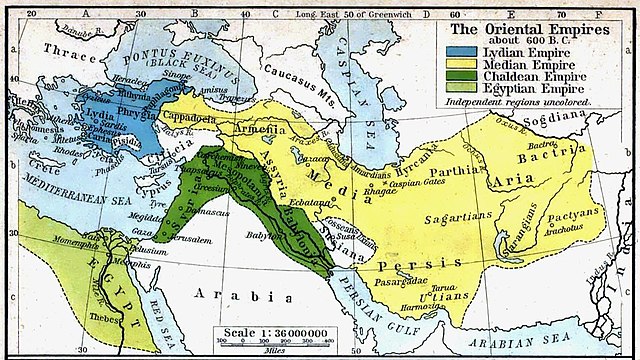

| PARTHIA

The region of Parthia within the empire of Medes, c. 600 BC; from a historical atlas illustrated by William Robert Shepherd

Capital : Nisa

Parthia is a historical region located in north-eastern Iran. It was conquered and subjugated by the empire of the Medes during the 7th century BC, was incorporated into the subsequent Achaemenid Empire under Cyrus the Great in the 6th century BC, and formed part of the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire following the 4th-century-BC conquests of Alexander the Great. The region later served as the political and cultural base of the Eastern-Iranian Parni people and Arsacid dynasty, rulers of the Parthian Empire (247 BC – 224 AD). The Sasanian Empire, the last state of pre-Islamic Iran, also held the region and maintained the Seven Parthian clans as part of their feudal aristocracy.

Name :

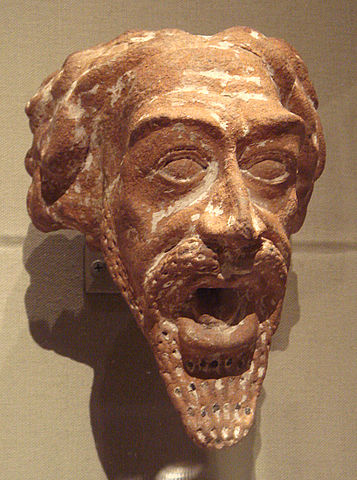

Xerxes I tomb, Parthian soldier circa 470 BCE The name "Parthia" is a continuation from Latin Parthia, from Old Persian Parthava, which was the Parthian language self-designator signifying "of the Parthians" who were an Iranian people. In context to its Hellenistic period, Parthia also appears as Parthyaea.

Geography

:

During Arsacid times, Parthia was united with Hyrcania as one administrative unit, and that region is therefore often (subject to context) considered a part of Parthia proper.

History

:

Parthia, as one of the 24 subjects of the Achaemenid Empire, in the Egyptian Statue of Darius I As the region inhabited by Parthians, Parthia first appears as a political entity in Achaemenid lists of governorates ("satrapies") under their dominion. Prior to this, the people of the region seem to have been subjects of the Medes, and 7th century BC Assyrian texts mention a country named Partakka or Partukka (though this "need not have coincided topographically with the later Parthia").

A year after Cyrus the Great's defeat of the Median Astyages, Parthia became one of the first provinces to acknowledge Cyrus as their ruler, "and this allegiance secured Cyrus' eastern flanks and enabled him to conduct the first of his imperial campaigns – against Sardis." According to Greek sources, following the seizure of the Achaemenid throne by Darius I, the Parthians united with the Median king Phraortes to revolt against him. Hystaspes, the Achaemenid governor of the province (said to be father of Darius I), managed to suppress the revolt, which seems to have occurred around 522–521 BC.

The first indigenous Iranian mention of Parthia is in the Behistun inscription of Darius I, where Parthia is listed (in the typical Iranian clockwise order) among the governorates in the vicinity of Drangiana. The inscription dates to c. 520 BC. The center of the administration "may have been at [what would later be known as] Hecatompylus". The Parthians also appear in Herodotus' list of peoples subject to the Achaemenids; the historiographer treats the Parthians, Chorasmians, Sogdians and Areioi as peoples of a single satrapy (the 16th), whose annual tribute to the king he states to be only 300 talents of silver. This "has rightly caused disquiet to modern scholars."

At the Battle of Gaugamela in 331 BC between the forces of Darius III and those of Alexander the Great, one such Parthian unit was commanded by Phrataphernes, who was at the time Achaemenid governor of Parthia. Following the defeat of Darius III, Phrataphernes surrendered his governorate to Alexander when the Macedonian arrived there in the summer of 330 BC. Phrataphernes was reappointed governor by Alexander.

Under

the Seleucids :

In 316 BC, Stasander, a vassal of Seleucus I Nicator and governor of Bactria (and, it seems, also of Aria and Margiana) was appointed governor of Parthia. For the next 60 years, various Seleucids would be appointed governors of the province.

Coin of Andragoras, the last Seleucid satrap of Parthia. He proclaimed independence around 250 BC In 247 BC, following the death of Antiochus II, Ptolemy III seized control of the Seleucid capital at Antioch, and "so left the future of the Seleucid dynasty for a moment in question." Taking advantage of the uncertain political situation, Andragoras, the Seleucid governor of Parthia, proclaimed his independence and began minting his own coins.

Meanwhile, "a man called Arsaces, of Scythian or Bactrian origin, [was] elected leader of the Parni", an eastern-Iranian peoples from the Tajen/Tajend River valley, south-east of the Caspian Sea. Following the secession of Parthia from the Seleucid Empire and the resultant loss of Seleucid military support, Andragoras had difficulty in maintaining his borders, and about 238 BC – under the command of "Arsaces and his brother Tiridates"– the Parni invaded Parthia and seized control of Astabene (Astawa), the northern region of that territory, the administrative capital of which was Kabuchan (Kuchan in the vulgate).

A short while later the Parni seized the rest of Parthia from Andragoras, killing him in the process. Although an initial punitive expedition by the Seleucids under Seleucus II was not successful, the Seleucids under Antiochus III recaptured Arsacid controlled territory in 209 BC from Arsaces' (or Tiridates') successor, Arsaces II. Arsaces II sued for peace and accepted vassal status, and it was not until Arsaces II's grandson (or grand-nephew) Phraates I, that the Arsacids/Parni would again begin to assert their independence.

Under the Arsacids :

Coin of Mithridates I (R. 171 – 138 BC). The reverse shows Heracles, and the inscription "Great King Arsaces, friend of Greeks"

Reproduction of a Parthian archer as depicted on Trajan's Column

A sculpted head (broken off from a larger statue) of a Parthian soldier wearing a Hellenistic-style helmet, from the Parthian royal residence and necropolis of Nisa, 2nd century BC From their base in Parthia, the Arsacid dynasts eventually extended their dominion to include most of Greater Iran. They also quickly established several eponymous branches on the thrones of Armenia, Iberia, and Caucasian Albania. Even though the Arsacids only sporadically had their capital in Parthia, their power base was there, among the Parthian feudal families, upon whose military and financial support the Arsacids depended. In exchange for this support, these families received large tracts of land among the earliest conquered territories adjacent to Parthia, which the Parthian nobility then ruled as provincial rulers. The largest of these city-states were Kuchan, Semnan, Gorgan, Merv, Zabol and Yazd.

From about 105 BC onwards, the power and influence of this handful of Parthian noble families was such that they frequently opposed the monarch, and would eventually be a "contributory factor in the downfall" of the dynasty.

From about 130 BC onwards, Parthia suffered numerous incursions by various nomadic tribes, including the Sakas, the Yuezhi, and the Massagetae. Each time, the Arsacid dynasts responded personally, doing so even when there were more severe threats from Seleucids or Romans looming on the western borders of their empire (as was the case for Mithridates I). Defending the empire against the nomads cost Phraates II and Artabanus I their lives.

The Roman Crassus attempted to conquer Parthia in 52 BC but was decisively defeated at the Battle of Carrhae. Caesar was planning another invasion when he was assassinated in 44 BC. A long series of Roman-Parthian wars followed.

Around 32 BC, civil war broke out when a certain Tiridates rebelled against Phraates IV, probably with the support of the nobility that Phraates had previously persecuted. The revolt was initially successful, but failed by 25 BC. In 9/8, the Parthian nobility succeeded in putting their preferred king on the throne, but Vonones proved to have too tight a budgetary control, so he was usurped in favor of Artabanus II, who seems to have been a non-Arsacid Parthian nobleman. But when Artabanus attempted to consolidate his position (at which he was successful in most instances), he failed to do so in the regions where the Parthian provincial rulers held sway.

By the 2nd century AD, the frequent wars with neighboring Rome and with the nomads, and the infighting among the Parthian nobility had weakened the Arsacids to a point where they could no longer defend their subjugated territories. The empire fractured as vassalaries increasingly claimed independence or were subjugated by others, and the Arsacids were themselves finally vanquished by the Persian Sassanids, a formerly minor vassal from southwestern Iran, in April 224.

Under

the Sasanians :

Language and literature :

The Parthians spoke Parthian, a north-western Iranian language. No Parthian literature survives from before the Sassanid period in its original form, and they seem to have written down only very little. The Parthians did, however, have a thriving oral minstrel-poet culture, to the extent that their word for minstrel – gosan – survives to this day in many Iranian languages as well as especially in Armenian ("gusan"), on which it practised heavy (especially lexical and vocabulary) influence. These professionals were evident in every facet of Parthian daily life, from cradle to grave, and they were entertainers of kings and commoners alike, proclaiming the worthiness of their patrons through association with mythical heroes and rulers. These Parthian heroic poems, "mainly known through Persian of the lost Middle Persian Xwaday-namag, and notably through Firdausi's Shahnameh, [were] doubtless not yet wholly lost in the Khurasan of [Firdausi's] day."

In Parthia itself, attested use of written Parthian is limited to the nearly 3,000 ostraca found (in what seems to have been a wine storage) at Nisa, in present-day Turkmenistan. A handful of other evidence of written Parthian has also been found outside Parthia; the most important of these being the part of a land-sale document found at Avroman (in the Kermanshah province of Iran), and more ostraca, graffiti and the fragment of a business letter found at Dura-Europos in present-day Syria.

The Parthian Arsacids do not seem to have used Parthian until relatively late, and the language first appears on Arsacid coinage during the reign of Vologases I (51–58 AD). Evidence that use of Parthian was nonetheless widespread comes from early Sassanid times; the declarations of the early Persian kings were – in addition to their native Middle Persian – also inscribed in Parthian.

Society :

Parthian waterspout, 1st – 2nd century AD City-states of "some considerable size" existed in Parthia as early as the 1st millennium BC, "and not just from the time of the Achaemenids or Seleucids." However, for the most part, society was rural, and dominated by large landholders with large numbers of serfs, slaves, and other indentured labor at their disposal. Communities with free peasants also existed.

By Arsacid times, Parthian society was divided into the four classes (limited to freemen). At the top were the kings and near family members of the king. These were followed by the lesser nobility and the general priesthood, followed by the mercantile class and lower-ranking civil servants, and with farmers and herdsmen at the bottom.

Little is known of the Parthian economy, but agriculture must have played the most important role in it. Significant trade first occurs with the establishment of the Silk road in 114 BC, when Hecatompylos became an important junction.

Parthian

cities :

•

Asaak

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |