| PERSIANS The Persians are an Iranian ethnic group that make up over half the population of Iran. They share a common cultural system and are native speakers of the Persian language, as well as languages closely related to Persian.

The ancient Persians were originally an ancient Iranian people who migrated to the region of Persis, corresponding to the modern province of Fars in southwestern Iran, by the ninth century BC. Together with their compatriot allies, they established and ruled some of the world's most powerful empires, well-recognized for their massive cultural, political, and social influence covering much of the territory and population of the ancient world. Throughout history, Persians have contributed greatly to art and science. Persian literature is one of the world's most prominent literary traditions.

In contemporary terminology, people of Persian heritage native specifically to present-day Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan are referred to as Tajiks, whereas those in the Caucasus (primarily in the present-day Republic of Azerbaijan and the Russian federal subject of Dagestan), albeit heavily assimilated, are referred to as Tats. However, historically, the terms Tajik and Tat were used as synonymous and interchangeable with Persian. Many influential Persian figures hailed from outside Iran's present-day borders to the northeast in Central Asia and Afghanistan and to a lesser extent to the northwest in the Caucasus proper. In historical contexts, especially in English, "Persians" may be defined more loosely to cover all subjects of the ancient Persian polities, regardless of ethnic background.

Ethnonym

:

A Greek folk etymology connected the name to Perseus, a legendary character in Greek mythology. Herodotus recounts this story, devising a foreign son, Perses, from whom the Persians took the name. Apparently, the Persians themselves knew the story, as Xerxes I tried to use it to suborn the Argives during his invasion of Greece, but ultimately failed to do so.

History

of usage :

Some medieval and early modern Islamic sources also used cognates of the term Persian to refer to various Iranian peoples and languages, including the speakers of Khwarazmian, Mazanderani, and Old Azeri. 10th-century Iraqi historian Al-Masudi refers to Pahlavi, Dari, and Azari as dialects of the Persian language. In 1333, medieval Moroccan traveler and scholar Ibn Battuta referred to the Afghans of Kabul as a specific sub-tribe of the Persians. Lady Mary (Leonora Woulfe) Sheil, in her observation of Iran during the Qajar era, states that the Kurds and the Leks would consider themselves as belonging to the race of the "old Persians".

On 21 March 1935, former king of Iran Reza Shah of the Pahlavi dynasty issued a decree asking the international community to use the term Iran, the native name of the country, in formal correspondence. However, the term Persian is still historically used to designate the predominant population of the Iranian peoples living in the Iranian cultural continent.

History

:

Ancient Persian attire worn by soldiers and a nobleman. The History of Costume by Braun & Scheider (1861 – 1880) The ancient Persians were initially dominated by the Assyrians for much of the first three centuries after arriving in the region. However, they played a major role in the downfall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. The Medes, another group of ancient Iranian people, unified the region under an empire centered in Media, which would become the region's leading cultural and political power of the time by 612 BC. Meanwhile, under the dynasty of the Achaemenids, the Persians formed a vassal state to the central Median power. In 552 BC, the Achaemenid Persians revolted against the Median monarchy, leading to the victory of Cyrus the Great over the throne in 550 BC. The Persians spread their influence to the rest of what is considered to be the Iranian Plateau, and assimilated with the non-Iranian indigenous groups of the region, including the Elamites and the Mannaeans.

Map of the Achaemenid Empire at its greatest extent At its greatest extent, the Achaemenid Empire stretched from parts of Eastern Europe in the west to the Indus Valley in the east, making it the largest empire the world had yet seen. The Achaemenids developed the infrastructure to support their growing influence, including the establishment of the cities of Pasargadae and Persepolis. The empire extended as far as the limits of the Greek city states in modern-day mainland Greece, where the Persians and Athenians influenced each other in what is essentially a reciprocal cultural exchange. Its legacy and impact on the kingdom of Macedon was also notably huge, even for centuries after the withdrawal of the Persians from Europe following the Greco-Persian Wars.

Ancient Persian and Greek soldiers as depicted on a color reconstruction of the 4th-century BC Alexander Sarcophagus During the Achaemenid era, Persian colonists settled in Asia Minor. In Lydia (the most important Achaemenid satrapy), near Sardis, there was the Hyrcanian plain, which, according to Strabo, got its name from the Persian settlers that were moved from Hyrcania. Similarly near Sardis, there was the plain of Cyrus, which further signified the presence of numerous Persian settlements in the area. In all these centuries, Lydia and Pontus were reportedly the chief centers for the worship of the Persian gods in Asia Minor. According to Pausanias, as late as the second century AD, one could witness rituals which resembled the Persian fire ceremony at the towns of Hyrocaesareia and Hypaepa. Mithridates III of Cius, a Persian nobleman and part of the Persian ruling elite of the town of Cius, founded the Kingdom of Pontus in his later life, in northern Asia Minor. At the peak of its power, under the infamous Mithridates VI the Great, the Kingdom of Pontus also controlled Colchis, Cappadocia, Bithynia, the Greek colonies of the Tauric Chersonesos, and for a brief time the Roman province of Asia. After a long struggle with Rome in the Mithridatic Wars, Pontus was defeated; part of it was incorporated into the Roman Republic as the province of Bithynia and Pontus, and the eastern half survived as a client kingdom.

Following the Macedonian conquests, the Persian colonists in Cappadocia and the rest of Asia Minor were cut off from their co-religionists in Iran proper, but they continued to practice the Iranian faith of their forefathers. Strabo, who observed them in the Cappadocian Kingdom in the first century BC, records (XV.3.15) that these "fire kindlers" possessed many "holy places of the Persian Gods", as well as fire temples. Strabo, who wrote during the time of Augustus (r. 63 BC-14 AD), almost three hundred years after the fall of the Achaemenid Persian Empire, records only traces of Persians in western Asia Minor; however, he considered Cappadocia "almost a living part of Persia".

The Iranian dominance collapsed in 330 BC following the conquest of the Achaemenid Empire by Alexander the Great, but reemerged shortly after through the establishment of the Parthian Empire in 247 BC, which was founded by a group of ancient Iranian people rising from Parthia. Until the Parthian era, Iranian identity had an ethnic, linguistic, and religious value. However, it did not yet have a political import. The Parthian language, which was used as an official language of the Parthian Empire, left influences on Persian, as well as on the neighboring Armenian language.

A bas-relief at Naqsh-e Rustam depicting the victory of Sasanian ruler Shapur I over Roman ruler Valerian and Philip the Arab The Parthian monarchy was succeeded by the Persian dynasty of the Sasanians in 224 AD. By the time of the Sasanian Empire, a national culture that was fully aware of being Iranian took shape, partially motivated by restoration and revival of the wisdom of "the old sages" (danagan pešenigan). Other aspects of this national culture included the glorification of a great heroic past and an archaizing spirit. Throughout the period, Iranian identity reached its height in every aspect. Middle Persian, which is the immediate ancestor of Modern Persian and a variety of other Iranian dialects, became the official language of the empire and was greatly diffused among Iranians.

The Parthians and the Sasanians would also extensively interact with the Romans culturally. The Roman–Persian wars and the Byzantine–Sasanian wars would shape the landscape of Western Asia, Europe, the Caucasus, North Africa, and the Mediterranean Basin for centuries. For a period of over 400 years, the Sasanians and the neighboring Byzantines were recognized as the two leading powers in the world. Cappadocia in Late Antiquity, now well into the Roman era, still retained a significant Iranian character; Stephen Mitchell notes in the Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity: "Many inhabitants of Cappadocia were of Persian descent and Iranian fire worship is attested as late as 465".

Following the Arab conquest of the Sasanian Empire in the medieval times, the Arab caliphates established their rule over the region for the next several centuries, during which the long process of the Islamization of Iran took place. Confronting the cultural and linguistic dominance of the Persians, beginning by the Umayyad Caliphate, the Arab conquerors began to establish Arabic as the primary language of the subject peoples throughout their empire, sometimes by force, further confirming the new political reality over the region. The Arabic term Ajam, denoting "people unable to speak properly", was adopted as a designation for non-Arabs (or non-Arabic speakers), especially the Persians. Although the term had developed a derogatory meaning and implied cultural and ethnic inferiority, it was gradually accepted as a synonym for "Persian" and still remains today as a designation for the Persian-speaking communities native to the modern Arab states of the Middle East. A series of Muslim Iranian kingdoms were later established on the fringes of the declining Abbasid Caliphate, including that of the ninth-century Samanids, under the reign of whom the Persian language was used officially for the first time after two centuries of no attestation of the language, now having received the Arabic script and a large Arabic vocabulary. Persian language and culture continued to prevail after the invasions and conquests by the Mongols and the Turks (including the Ilkhanate, Ghaznavids, Seljuks, Khwarazmians, and Timurids), who were themselves significantly Persianized, further developing in Asia Minor, Central Asia, and South Asia, where Persian culture flourished by the expansion of the Persianate societies, particularly those of Turco-Persian and Indo-Persian blends.

After over eight centuries of foreign rule within the region, the Iranian hegemony was reestablished by the emergence of the Safavid Empire in the 16th century. Under the Safavid Empire, focus on Persian language and identity was further revived, and the political evolution of the empire once again maintained Persian as the main language of the country. During the times of the Safavids and subsequent modern Iranian dynasties such as the Qajars, architectural and iconographic elements from the time of the Sasanian Persian Empire were reincorporated, linking the modern country with its ancient past. Contemporary embracement of the legacy of Iran's ancient empires, with an emphasis on the Achaemenid Persian Empire, developed particularly under the reign of the Pahlavi dynasty, providing the motive of a modern nationalistic pride. Iran's modern architecture was then inspired by that of the country's classical eras, particularly with the adoption of details from the ancient monuments in the Achaemenid capitals Persepolis and Pasargadae and the Sasanian capital Ctesiphon. Fars, corresponding to the ancient province of Persia, with its modern capital Shiraz, became a center of interest, particularly during the annual international Shiraz Arts Festival and the 2,500th anniversary of the founding of the Persian Empire. The Pahlavi rulers modernized Iran, and ruled it until the 1979 Revolution.

Anthropology

:

Persian language :

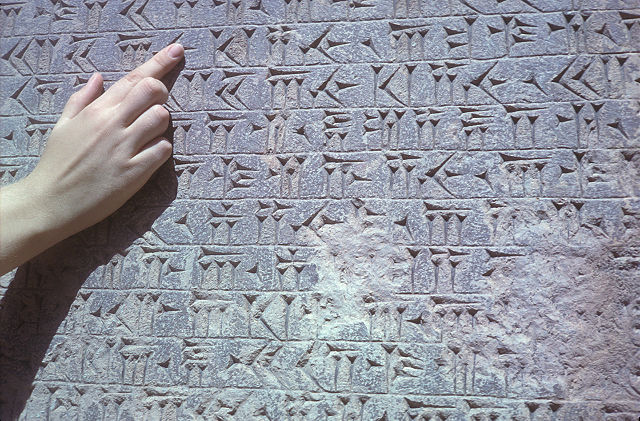

The Persian language belongs to the western group of the Iranian branch of the Indo-European language family. Modern Persian is classified as a continuation of Middle Persian, the official religious and literary language of the Sasanian Empire, itself a continuation of Old Persian, which was used by the time of the Achaemenid Empire. Old Persian is one of the oldest Indo-European languages attested in original text. Samples of Old Persian have been discovered in present-day Iran, Armenia, Egypt, Iraq, Romania (Gherla), and Turkey. The oldest attested text written in Old Persian is from the Behistun Inscription, a multilingual inscription from the time of Achaemenid ruler Darius the Great carved on a cliff in western Iran.

Related

groups :

The Tajiks are a people native to Tajikistan, Afghanistan, and Uzbekistan who speak Persian in a variety of dialects. The Tajiks of Tajikistan and Uzbekistan are native speakers of Tajik, which is the official language of Tajikistan, and those in Afghanistan speak Dari, one of the two official languages of Afghanistan.

The Tat people, an Iranian people native to the Caucasus (primarily living in the Republic of Azerbaijan and the Russian republic of Dagestan), speak a language (Tat language) that is closely related to Persian. The origin of the Tat people is traced to an Iranian-speaking population that was resettled in the Caucasus by the time of the Sasanian Empire.

The Lurs, an ethnic Iranian people native to western Iran, are often associated with the Persians and the Kurds. They speak various dialects of the Luri language, which is considered to be a descendant of Middle Persian.

The Hazaras, making up the third largest ethnic group in Afghanistan, speak a variety of Persian by the name of Hazaragi, which is more precisely a part of the Dari dialect continuum. The Aimaqs, a semi-nomadic people native to Afghanistan, speak a variety of Persian by the name of Aimaqi, which also belongs to the Dari dialect continuum.

Persian-speaking communities native to modern Arab countries are generally designated as Ajam, including the Ajam of Bahrain, the Ajam of Iraq, and the Ajam of Kuwait.

Culture

:

The artistic heritage of the Persians is eclectic and has included contributions from both the east and the west. Due to the central location of Iran, Persian art has served as a fusion point between eastern and western traditions. Persians have contributed to various forms of art, including calligraphy, carpet weaving, glasswork, lacquerware, marquetry (khatam), metalwork, miniature illustration, mosaic, pottery, and textile design.

5th-century BC Achaemenid gold vessels. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Ancient Iranian goddess Anahita depicted on a Sasanian silver vessel. Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland

Sasanian marble bust. National Museum of Iran, Tehran

17th-century Persian potteries from Isfahan. Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto Literature

:

Not all Persian literature is written in Persian, as works written by Persians in other languages—such as Arabic and Greek—might also be included. At the same time, not all literature written in Persian is written by ethnic Persians or Iranians, as Turkic, Caucasian, and Indic authors have also used Persian literature in the environment of Persianate cultures.

Architecture

:

The architectural heritage of the Sasanian Empire includes, among others, castle fortifications such as the Fortifications of Derbent (located in North Caucasus, now part of Russia), the Rudkhan Castle and the Shapur-Khwast Castle, palaces such as the Palace of Ardashir and the Sarvestan Palace, bridges such as the Shahrestan Bridge and the Shapuri Bridge, the Archway of Ctesiphon, and the reliefs at Taq-e Bostan.

Ruins of the Tachara, Persepolis

Tomb of Cyrus, Pasargadae

The Sasanian reliefs at Taq-e Bostan

Shapur-Khwast Castle, Khorramabad Architectural elements from the time of Iran's ancient Persian empires have been adopted and incorporated in later period. They were used especially during the modernization of Iran under the reign of the Pahlavi dynasty to contribute to the characterization of the modern country with its ancient history.

Gardens

:

"The Great King [Cyrus II]...in all the districts he resides in and visits, takes care that there are parádeisos ("paradise") as they [Persians] call them, full of the good and beautiful things that the soil produce."

The Persian garden, the earliest examples of which were found throughout the Achaemenid Empire, has an integral position in Persian architecture. Gardens assumed an important place for the Achaemenid monarchs, and utilized the advanced Achaemenid knowledge of water technologies, including aqueducts, earliest recorded gravity-fed water rills, and basins arranged in a geometric system. The enclosure of this symmetrically arranged planting and irrigation by an infrastructure such as a palace created the impression of "paradise". The word paradise itself originates from Avestan pairidaeza (Old Persian paridaida; New Persian pardis, ferdows), which literally translates to "walled-around". Characterized by its quadripartite (carbaq) design, the Persian garden was evolved and developed into various forms throughout history, and was also adopted in various other cultures in Eurasia. It was inscribed on UNESCO's World Heritage List in June 2011.

Shah Square, Isfahan

Eram Garden, Shiraz

Tomb of Hafez, Shiraz

Shazdeh Garden, Kerman Carpets :

Carpet weaving is an essential part of the Persian culture, and Persian rugs are said to be one of the most detailed hand-made works of art. Achaemenid rug and carpet artistry is well recognized. Xenophon describes the carpet production in the city of Sardis, stating that the locals take pride in their carpet production. A special mention of Persian carpets is also made by Athenaeus of Naucratis in his Deipnosophistae, as he describes a "delightfully embroidered" Persian carpet with "preposterous shapes of griffins".

The Pazyryk carpet, a Scythian pile-carpet dating back to the 4th century BC that is regarded as the world's oldest existing carpet, depicts elements of Assyrian and Achaemenid designs, including stylistic references to the stone slab designs found in Persian royal buildings.

Music :

Dancers and musical instrument players depicted on a Sasanian silver bowl from the 5th-7th century AD According to the accounts reported by Xenophon, a great number of singers were present at the Achaemenid court. However, little information is available from the music of that era. The music scene of the Sasanian Empire has a more available and detailed documentation than the earlier periods, and is especially more evident within the context of Zoroastrian musical rituals. Overall, Sasanian music was influential and was adopted in the subsequent eras.

Iranian music, as a whole, utilizes a variety of musical instruments that are unique to the region, and has remarkably evolved since the ancient and medieval times. In traditional Sasanian music, the octave was divided into seventeen tones. By the end of the 13th century, Iranian music also maintained a twelve-interval octave, which resembled the western counterparts.

Observances

:

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

.svg.png)