| SAKA

A cataphract-style parade armour of a Saka royal, also known as "The Golden Warrior", from the Issyk kurgan, a historical burial site near ex-capital city of Almaty, Kazakhstan. Circa 400-200 BC The Saka, Shak, Saka or Sacae (Old Persian: Saka; Brahmi: Sak; Sanskrit: Shak, Saka, Saka; Ancient Greek: Sákai; Latin: Sacae; Chinese: old mod. Sai) were a group of nomadic Iranian peoples who historically inhabited the northern and eastern Eurasian Steppe and the Tarim Basin.

Though closely related, the Sakas are to be distinguished from the Scythians of the Pontic Steppe and the Massagetae of the Aral Sea region, although they form part of the wider Scythian cultures. Like the Scythians, the Sakas were ultimately derived from the earlier Andronovo culture. Their language formed part of the Scythian languages. Prominent archaeological remains of the Sakas include Arzhan, Tunnug, the Pazyryk burials, the Issyk kurgan, Saka Kurgan tombs, the Barrows of Tasmola and possibly Tillya Tepe.

In the 2nd century BC, many Sakas were driven by the Yuezhi from the steppe into Sogdia and Bactria and then to the northwest of the Indian subcontinent, where they were known as the Indo-Scythians. Other Sakas invaded the Parthian Empire, eventually settling in Sistan, while others may have migrated to the Dian Kingdom in Yunnan, China. In the Tarim Basin and Taklamakan Desert region of Northwest China, they settled in Khotan, Yarkand, Kashgar and other places, which were at various times vassals to greater powers, such as Han China and Tang China.

Usage

of name :

Another people, the Gimirrai, who were known to the ancient Greeks as the Cimmerians, were closely associated with the Sakas. In Biblical Hebrew, the Ashkuz (Ashkenaz) are considered to be a direct offshoot from the Gimirri (Gomer).

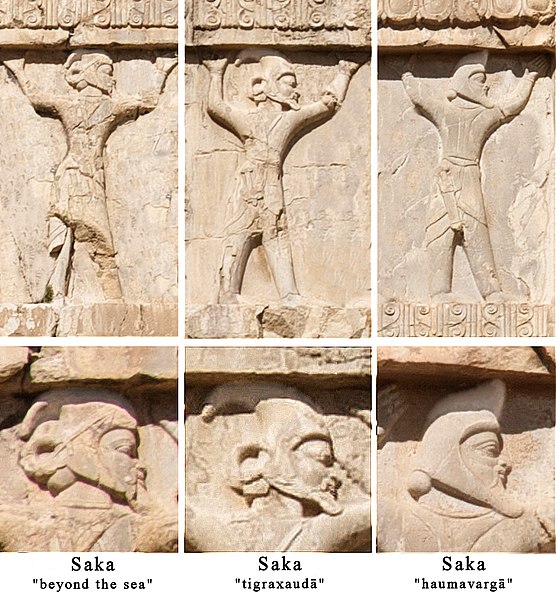

For the Achaemenids, there were three types of Sakas: the Saka tayai

paradraya ("beyond the sea", presumably between the Greeks

and the Thracians on the Western side of the Black Sea), the Saka

tigraxauda (“with pointed caps”), the Saka haumavarga

("Hauma drinkers", furthest East). Soldiers of the Achaemenid

army, Xerxes I tomb detail, circa 480 BC.

•

The Saka paradraya – "Saka beyond the sea", a name

added after the Scythian campaign of Darius I north of the Danube.

•

The Saka para Sugdam – "Saka beyond Sugda (Sogdia)",

a term was used by Darius for the people who formed the limits of

his empire at the opposite end to the Kingdom of Kush (the Ethiopians),

therefore should be located at the eastern edge of his empire.

Saka haumavarga is considered to be the same as Amyrgians, the Saka tribe in closest proximity to Bactria and Sogdia. It has been suggested that the Saka haumavarga may be the Saka para Sugdam, therefore Saka haumavarga is argued by some to be located further east than the Saka tigraxauda, perhaps at the Pamir Mountains or Xinjiang, although Syr Darya is considered to be their more likely location given that the name says "beyond Sogdia" rather than Bactria.

In the modern era, the archaeologist Hugo Winckler (1863–1913) was the first to associate the Sakas with the Scythians. John Manuel Cook, in The Cambridge History of Iran, states: "The Persians gave the single name Saka both to the nomads whom they encountered between the Hungry Steppe (Mirzacho'l) and the Caspian, and equally to those north of the Danube and Black Sea against whom Darius later campaigned; and the Greeks and Assyrians called all those who were known to them by the name Skuthai (Iškuzai). Saka and Skuthai evidently constituted a generic name for the nomads on the northern frontiers." Persian sources often treat them as a single tribe called the Saka (Sakai or Sakas), but Greek and Latin texts suggest that the Scythians were composed of many sub-groups.

Modern scholars now usually use the term Saka to refer to Iranian peoples who inhabited the northern and eastern Eurasian Steppe and the Tarim Basin.

History :

Artifacts found the tombs 2 and 4 of Tillya Tepe and reconstitution of their use on the man and woman found in these tombs

Origins :

Early

history :

Two Saka tribes named in the Behistun Inscription, Saka tigraxauda ("Saka with pointy hats/caps") and the Saka haumavarga ("haoma-drinking saka"), may be located to the east of the Caspian Sea. Some argued that the Saka haumavarga may be the Saka para Sugdam, therefore Saka haumavarga would be located further east than the Saka tigraxauda. Some argued for the Pamirs or Xinjiang as their location, although Jaxartes is considered to be their more likely location given that the name says "beyond Sogdiana" rather than Bactria.

The contemporary Greek historian Herodotus noted that the Achaemenid Empire called all of the "Scythians" by the name "Saka".

Greek historians wrote of the wars between the Saka and the Medes, as well as their wars against Cyrus the Great of the Persian Achaemenid Empire where Saka women were said to fight alongside their men. According to Herodotus, Cyrus the Great confronted the Massagetae, a people related to the Saka, while campaigning to the east of the Caspian Sea and was killed in the battle in 530 BC. Darius I also waged wars against the eastern Sakas, who fought him with three armies led by three kings according to Polyaenus. In 520–519 BC, Darius I defeated the Saka tigraxauda tribe and captured their king Skunkha (depicted as wearing a pointed hat in Behistun). The territories of Saka were absorbed into the Achaemenid Empire as part of Chorasmia that included much of the Amu Darya (Oxus) and the Syr Darya (Jaxartes), and the Saka then supplied the Achaemenid army with large number of mounted bowmen. They were also mentioned as among those who resisted Alexander the Great's incursions into Central Asia.

The Saka were known as the Sak or Sai in ancient Chinese records. These records indicate that they originally inhabited the Ili and Chu River valleys of modern Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. In the Book of Han, the area was called the "land of the Sak", i.e. the Saka. The exact date of the Sakas' arrival in the valleys of the Ili and Chu in Central Asia is unclear, perhaps it was just before the reign of Darius I. Around 30 Saka tombs in the form of kurgans (burial mounds) have also been found in the Tian Shan area dated to between 550–250 BC. Indications of Saka presence have also been found in the Tarim Basin region, possibly as early as the 7th century BC. At least by the late 2nd century BC, the Sakas had founded states in the Tarim Barin.

Migrations :

Captured Saka king Skunkha, from Mount Behistun, Iran, Achaemenid stone relief from the reign of Darius I (r. 522 – 486 BC) The Saka were pushed out of the Ili and Chu River valleys by the Yuezhi. An account of the movement of these people is given in Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian. The Yuehzhi, who originally lived between Tängri Tagh (Tian Shan) and Dunhuang of Gansu, China, were assaulted and forced to flee from the Hexi Corridor of Gansu by the forces of the Xiongnu ruler Modu Chanyu, who conquered the area in 177–176 BC. In turn the Yuehzhi were responsible for attacking and pushing the Sai (i.e. Saka) west into Sogdiana, where, between 140 and 130 BCE, the latter crossed the Syr Darya into Bactria. The Saka also moved southwards toward the Pamirs and northern India, where they settled in Kashmir, and eastward, to settle in some of the oasis-states of Tarim Basin sites, like Yanqi (Karasahr) and Qiuci (Kuch). The Yuehzhi, themselves under attacks from another nomadic tribe, the Wusun, in 133–132 BC, moved, again, from the Ili and Chu valleys, and occupied the country of Daxia, ("Bactria").

The ancient Greco-Roman geographer Strabo noted that the four tribes that took down the Bactrians in the Greek and Roman account – the Asioi, Pasianoi, Tokharoi and Sakaraulai – came from land north of the Syr Darya where the Ili and Chu valleys are located. Identification of these four tribes varies, but Sakaraulai may indicate an ancient Saka tribe, the Tokharoi is possibly the Yuezhi, and while the Asioi had been proposed to be groups such as the Wusun or Alans.

René Grousset wrote of the migration of the Saka: "the Saka, under pressure from the Yueh-chih [Yuezhi], overran Sogdiana and then Bactria, there taking the place of the Greeks." Then, "Thrust back in the south by the Yueh-chih," the Saka occupied "the Saka country, Sakastan, whence the modern Persian Seistan." Some of the Saka fleeing the Yuezhi attacked the Parthian Empire, where they defeated and killed the kings Phraates II and Artabanus. These Sakas were eventually settled by Mithridates II in what become known as Sakastan. According to Harold Walter Bailey, the territory of Drangiana (now in Afghanistan and Pakistan) became known as "Land of the Sakas", and was called Sakastan in the Persian language of contemporary Iran, in Armenian as Sakastan, with similar equivalents in Pahlavi, Greek, Sogdian, Syriac, Arabic, and the Middle Persian tongue used in Turfan, Xinjiang, China. This is attested in a contemporary Kharosthi inscription found on the Mathura lion capital belonging to the Saka kingdom of the Indo-Scythians (200 BC – 400 AD) in North India, roughly the same time the Chinese record that the Saka had invaded and settled the country of Jibin (i.e. Kashmir, of modern-day India and Pakistan).

Iaroslav Lebedynsky and Victor H. Mair speculate that some Sakas may also have migrated to the area of Yunnan in southern China following their expulsion by the Yuezhi. Excavations of the prehistoric art of the Dian Kingdom of Yunnan have revealed hunting scenes of Caucasoid horsemen in Central Asian clothing. The scenes depicted on these drums sometimes represent these horsemen practising hunting. Animal scenes of felines attacking oxen are also at times reminiscent of Scythian art both in theme and in composition.

Migrations of the 2nd and 1st century BC have left traces in Sogdia and Bactria, but they cannot firmly be attributed to the Saka, similarly with the sites of Sirkap and Taxila in ancient India. The rich graves at Tillya Tepe in Afghanistan are seen as part of a population affected by the Saka.

The Shakya clan of India, to which Gautam Buddh, called Sakyamuni "Sage of the Shakyas", belonged, were also likely Sakas, as Michael Witzel and Christopher I. Beckwith have demonstrated.

Indo-Scythians

:

Kingdoms

in the Tarim Basin :

Coin of Gurgamoya, king of Khotan. Khotan, first century

Obv: Kharosthi legend, "Of the great king of kings, king of Khotan, Gurgamoya

Rev: Chinese legend: "Twenty-four grain copper coin". British Museum The Kingdom of Khotan was a Saka city state in on the southern edge of the Tarim Basin. As a consequence of the Han–Xiongnu War spanning from 133 BCE to 89 CE, the Tarim Basin (now Xinjiang, Northwest China), including Khotan and Kashgar, fell under Han Chinese influence, beginning with the reign of Emperor Wu of Han (r. 141-87 BC).

Archaeological evidence and documents from Khotan and other sites in the Tarim Basin provided information on the language spoken by the Saka. The official language of Khotan was initially Gandhari Prakrit written in Kharosthi, and coins from Khotan dated to the 1st century bear dual inscriptions in Chinese and Gandhari Prakrit, indicating links of Khotan to both India and China. Surviving documents however suggest that an Iranian language was used by the people of the kingdom for a long time Third-century AD documents in Prakrit from nearby Shanshan record the title for the king of Khotan as hinajha (i.e. "generalissimo"), a distinctively Iranian-based word equivalent to the Sanskrit title senapati, yet nearly identical to the Khotanese Saka hinaysa attested in later Khotanese documents. This, along with the fact that the king's recorded regnal periods were given as the Khotanese k?u?a, "implies an established connection between the Iranian inhabitants and the royal power," according to the Professor of Iranian Studies Ronald E. Emmerick. He contended that Khotanese-Saka-language royal rescripts of Khotan dated to the 10th century "makes it likely that the ruler of Khotan was a speaker of Iranian." Furthermore, he argued that the early form of the name of Khotan, hvatana, is connected semantically with the name Saka.

The region once again came under Chinese suzerainty with the campaigns of conquest by Emperor Taizong of Tang (r. 626-649). From the late eighth to ninth centuries, the region changed hands between the rival Tang and Tibetan Empires. However, by the early 11th century the region fell to the Muslim Turkic peoples of the Kara-Khanid Khanate, which led to both the Turkification of the region as well as its conversion from Buddhism to Islam.

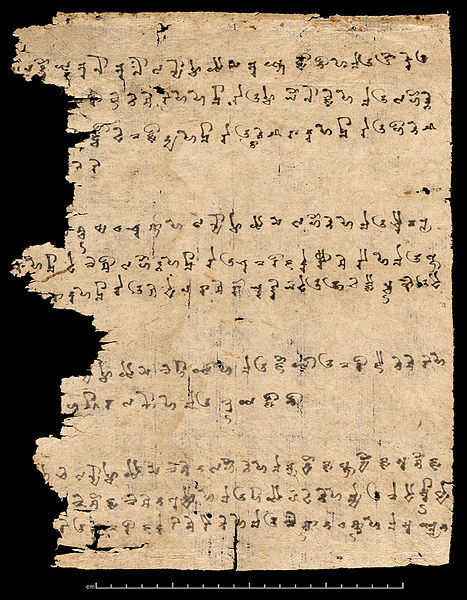

A document from Khotan written in Khotanese Saka, part of the Eastern

Iranian branch of the Indo-European languages, listing the animals

of the Chinese zodiac in the cycle of predictions for people born

in that year; ink on paper, early 9th century.

Although the ancient Chinese had called Khotan Yutian, another more native Iranian name occasionally used was Jusadanna, derived from Indo-Iranian Gostan and Gostana, the names of the town and region around it, respectively.

Shule

Kingdom :

Historiography

:

The

Sacae, or Scyths, were clad in trousers, and had on their heads

tall stiff caps rising to a point. They bore the bow of their country

and the dagger; besides which they carried the battle-axe, or sagaris.

They were in truth Amyrgian (Western) Scythians, but the Persians

called them Sacae, since that is the name which they gave to all

Scythians.

Scythia and the Parthian Empire in about 170 BC (before the Yuezhi invaded Bactria) In the 1st century BC, the Greek-Roman geographer Strabo gave an extensive description of the peoples of the eastern steppe, whom he located in Central Asia beyond Bactria and Sogdiana.

Strabo went on to list the names of the various tribes he believed to be "Scythian", and in so doing almost certainly conflated them with unrelated tribes of eastern Central Asia. These tribes included the Saka.

Now the greater part of the Scythians, beginning at the Caspian Sea, are called Däae, but those who are situated more to the east than these are named Massagetae and Sacae, whereas all the rest are given the general name of Scythians, though each people is given a separate name of its own. They are all for the most part nomads. But the best known of the nomads are those who took away Bactriana from the Greeks, I mean the Asii, Pasiani, Tochari, and Sacarauli, who originally came from the country on the other side of the Iaxartes River that adjoins that of the Sacae and the Sogdiani and was occupied by the Sacae. And as for the Däae, some of them are called Aparni, some Xanthii, and some Pissuri. Now of these the Aparni are situated closest to Hyrcania and the part of the sea that borders on it, but the remainder extend even as far as the country that stretches parallel to Aria. Between them and Hyrcania and Parthia and extending as far as the Arians is a great waterless desert, which they traversed by long marches and then overran Hyrcania, Nesaea, and the plains of the Parthians. And these people agreed to pay tribute, and the tribute was to allow the invaders at certain appointed times to overrun the country and carry off booty. But when the invaders overran their country more than the agreement allowed, war ensued, and in turn their quarrels were composed and new wars were begun. Such is the life of the other nomads also, who are always attacking their neighbors and then in turn settling their differences.

(Strabo,

Geography, 11.8.1; transl. 1903 by H. C. Hamilton & W. Falconer.)

Silver coin of the Indo-Scythian King Azes II (ruled c. 35–12 BC). Note the royal tamga on the coin The Sakas receive numerous mentions in Indian texts, including the Purans, the Manusmriti, the Ramayan, the Mahabharat, and the Mahabhashya of Patanjali.

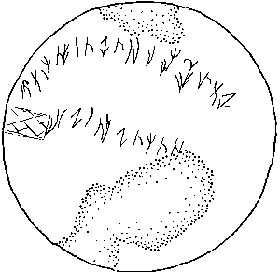

Language : Issyk inscription

Issyk dish with inscription

Drawing of the Issyk inscription Modern scholarly consensus is that the Eastern Iranian language ancestral to the Pamir languages in Central Asia and the medieval Saka language of Xinjiang, was one of the Scythian languages. Evidence of the Middle Iranian "Scytho-Khotanese" language survives in Northwest China, where Khotanese-Saka-language documents, ranging from medical texts to Buddhist texts, have been found primarily in Khotan and Tumshuq (northeast of Kashgar). They largely predate the Islamization of Xinjiang under the Turkic-speaking Kara-Khanid Khanate. Similar documents, the Dunhuang manuscripts, were discovered written in the Khotanese Saka language and date mostly from the tenth century.

Attestations of the Saka language show that it was an Eastern Iranian language. The linguistic heartland of Saka was the Kingdom of Khotan, which had two varieties, corresponding to the major settlements at Khotan (now called Hotan) and Tumshuq (now titled Tumxuk). Tumshuqese and Khotanese varieties of Saka contain many borrowings from the Middle Indo-Aryan languages, but also share features with the modern Eastern Iranian languages Wakhi and Pashto.

The Issyk inscription, a short fragment on a silver cup found in the Issyk kurgan in Kazakhstan is believed to be an early example of Saka, constituting one of very few autochthonous epigraphic traces of that language. [citation needed] The inscription is in a variant of Kharosthi. Harmatta identifies the dialect as Khotanese Saka, tentatively translating its as: "The vessel should hold wine of grapes, added cooked food, so much, to the mortal, then added cooked fresh butter on".

A growing body of both linguistic and physical anthropological evidence suggest the Wakhi are descendants of Saka. According to the Indo-Europeanist Martin Kümmel, Wakhi may be classified as a Western Saka dialect; the other attested Saka dialects, Khotanese and Tumshuqese, would then be classified as Eastern Saka.

The Saka heartland was gradually conquered during the Turkic expansion, beginning in the sixth century, and the area was gradually Turkified linguistically under the Uyghurs.

Genetics :

The earliest studies could only analyze segments of mtDNA, thus providing only broad correlations of affinity to modern West Eurasian or East Eurasian populations. For example, in a 2002 study the mitochondrial DNA of Saka period male and female skeletal remains from a double inhumation kurgan at the Beral site in Kazakhstan was analysed. The two individuals were found to be not closely related. The HV1 mitochondrial sequence of the male was similar to the Anderson sequence which is most frequent in European populations. The HV1 sequence of the female suggested a greater likelihood of Asian origins.

More recent studies have been able to type for specific mtDNA lineages. For example, a 2004 study examined the HV1 sequence obtained from a male "Scytho-Siberian" at the Kizil site in the Altai Republic. It belonged to the N1a maternal lineage, a geographically West Eurasian lineage. Another study by the same team, again of mtDNA from two Scytho-Siberian skeletons found in the Altai Republic, showed that they had been typical males "of mixed Euro-Mongoloid origin". One of the individuals was found to carry the F2a maternal lineage, and the other the D lineage, both of which are characteristic of East Eurasian populations.

These early studies have been elaborated by an increasing number of studies by Russian scholars. Conclusions are (i) an early, Bronze Age mixing of both west and east Eurasian lineages, with western lineages being found far to the east, but not vice versa; (ii) an apparent reversal by Iron Age times, with an increasing presence of East Eurasian lineages in the western steppe; (iii) the possible role of migrations from the south, the Balkano-Danubian and Iranian regions, toward the steppe.

Ancient Y-DNA data was finally provided by Keyser et al in 2009. They studied the haplotypes and haplogroups of 26 ancient human specimens from the Krasnoyarsk area in Siberia dated from between the middle of the 2nd millennium BC and the 4th century AD (Scythian and Sarmatian timeframe). Nearly all subjects belonged to haplogroup R-M17. The authors suggest that their data shows that between the Bronze and the Iron Ages the constellation of populations known variously as Scythians, Andronovians, etc. were blue- (or green-) eyed, fair-skinned and light-haired people who might have played a role in the early development of the Tarim Basin civilisation. Moreover, this study found that they were genetically more closely related to modern populations in eastern Europe than those of central and southern Asia. The ubiquity and dominance of the R1a Y-DNA lineage contrasted markedly with the diversity seen in the mtDNA profiles.

A genetic study published in Nature in May 2018 examined the remains of twenty-eight Sakas buried between ca. 900 BC to AD 1, compromising eight Sakas of southern Siberia (Tagar culture), eight Sakas of the central steppe (Tasmola culture), and twelve Sakas of the Tian Shan. The six samples of Y-DNA extracted from the Tian Shan Saka belonged to the haplogroups R (four samples), R1 and R1a1. The samples of mtDNA extracted from the Tien Shan Saka belonged to C4, H4d, T2a1, U5a1d2b, H2a, U5a1a1, HV6 (two samples), D4j8 (two samples), W1c and G2a1. The study detected significant genetic differences between the Sakas and Scythians of the Pannonian Basin, and between Sakas of southern Siberia, the central steppe and the Tian Shan. Tian Shan Sakas were found to be of about 70% Western Steppe Herder (WSH) ancestry, 25% Siberian Hunter-Gatherer ancestry and 5% Iranian Neolithic ancestry. The Iranian Neolithic ancestry was primarily male-derived, probably from the Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex. Sakas of the Tasmola culture were found to be of about 56% WSH ancestry and 44% Siberian Hunter-Gather ancestry. The peoples of the Tagar culture had about 83,5% WSH ancestry, 9% Ancient North Eurasian (ANE) ancestry and 7,5% Siberian Hunter-Gatherer ancestry. The study suggested that the Saka were the source of west Eurasian ancestry among the Xiongnu, and that the Huns probably emerged through conquests of Sakas by the Xiongnu, which is characterized by increased levels of East Asian paternal ancestry in Central Asia.

Physical

appearance :

The 2nd century BC Han Chinese envoy Zhang Qian described the Sai (Saka) as having yellow (probably meaning hazel or green), and blue eyes. In Natural History, the 1st century AD Roman author Pliny the Elder characterises the Seres, sometimes identified as Sala or Tocharians, as red-haired and blue-eyed.

Archaeology :

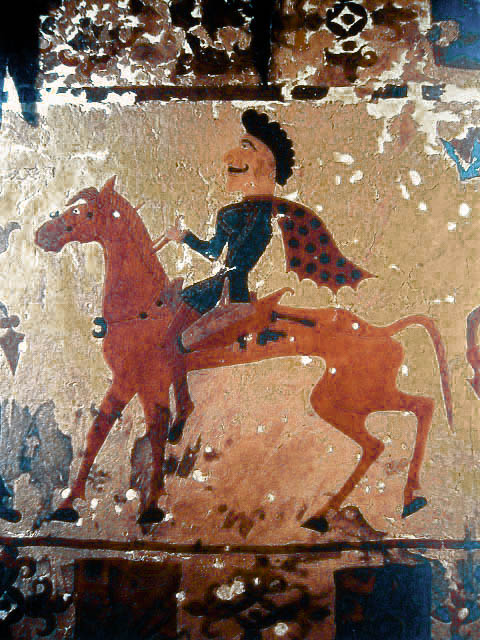

A Pazyryk horseman in a felt painting from a burial around 300 BC. The Pazyryks appear to be closely related to the Scythians The spectacular grave-goods from Arzhan, and others in Tuva, have been dated from about 900 BC onward, and are associated with the Saka. Burials at Pazyryk in the Altay Mountains have included some spectacularly preserved Sakas of the "Pazyryk culture" – including the Ice Maiden of the 5th century BC.

Pazyryk

culture :

The Pazyryk culture flourished between the 7th and 3rd century BC in the area associated with the Sacae.

Ordinary Pazyryk graves contain only common utensils, but in one, among other treasures, archaeologists found the famous Pazyryk Carpet, the oldest surviving wool-pile oriental rug. Another striking find, a 3-metre-high four-wheel funerary chariot, survived well-preserved from the 5th to 4th century BC.

Tillia

Tepe treasure :

A high degree of cultural syncretism pervades the findings, however. Hellenistic cultural and artistic influences appear in many of the forms and human depictions (from amorini to rings with the depiction of Athena and her name inscribed in Greek), attributable to the existence of the Seleucid empire and Greco-Bactrian kingdom in the same area until around 140 BC, and the continued existence of the Indo-Greek kingdom in the northwestern Indian sub-continent until the beginning of our era. This testifies to the richness of cultural influences in the area of Bactria at that time.

Culture

:

The art of the Saka was of a similar styles as other Iranian peoples of the steppes, which is referred to collectively as Scythian art. In 2001, the discovery of an undisturbed royal Scythian burial-barrow illustrated Scythian animal-style gold that lacks the direct influence of Greek styles. Forty-four pounds of gold weighed down the royal couple in this burial, discovered near Kyzyl, capital of the Siberian republic of Tuva.

Ancient influences from Central Asia became identifiable in China following contacts of metropolitan China with nomadic western and northwestern border territories from the 8th century BC. The Chinese adopted the Scythian-style animal art of the steppes (descriptions of animals locked in combat), particularly the rectangular belt-plaques made of gold or bronze, and created their own versions in jade and steatite.

Following their expulsion by the Yuezhi, some Saka may also have migrated to the area of Yunnan in southern China. Saka warriors could also have served as mercenaries for the various kingdoms of ancient China. Excavations of the prehistoric art of the Dian civilisation of Yunnan have revealed hunting scenes of Caucasoid horsemen in Central Asian clothing.

Saka influences have been identified as far as Korea and Japan. Various Korean artifacts, such as the royal crowns of the kingdom of Silla, are said to be of "Scythian" design. Similar crowns, brought through contacts with the continent, can also be found in Kofun era Japan.

Society

:

Clothing :

Royal crown, Tillia Tepe

"Kings with dragons", Tillia Tepe Similar to other eastern Iranian peoples represented on the reliefs of the Apadana at Persepolis, Sakas are depicted as wearing long trousers, which cover the uppers of their boots. Over their shoulders they trail a type of long mantle, with one diagonal edge in back. One particular tribe of Sakas (the Saka tigraxauda) wore pointed caps. Herodotus in his description of the Persian army mentions the Sakas as wearing trousers and tall pointed caps.

Herodotus says Sakas had "high caps tapering to a point and stiffly upright." Asian Saka headgear is clearly visible on the Persepolis Apadana staircase bas-relief – high pointed hat with flaps over ears and the nape of the neck. From China to the Danube delta, men seemed to have worn a variety of soft headgear – either conical like the one described by Herodotus, or rounder, more like a Phrygian cap.

Saka women dressed in much the same fashion as men. A Pazyryk burial, discovered in the 1990s, contained the skeletons of a man and a woman, each with weapons, arrowheads, and an axe. Herodotus mentioned that Sakas had "high caps and … wore trousers." Clothing was sewn from plain-weave wool, hemp cloth, silk fabrics, felt, leather and hides.

Pazyryk findings give the most number of almost fully preserved garments and clothing worn by the Scythian/Saka peoples. Ancient Persian bas-reliefs, inscriptions from Apadana and Behistun and archaeological findings give visual representations of these garments.

Based on the Pazyryk findings (can be seen also in the south Siberian, Uralic and Kazakhstan rock drawings) some caps were topped with zoomorphic wooden sculptures firmly attached to a cap and forming an integral part of the headgear, similar to the surviving nomad helmets from northern China. Men and warrior women wore tunics, often embroidered, adorned with felt applique work, or metal (golden) plaques.

Persepolis Apadana again serves a good starting point to observe the tunics of the Sakas. They appear to be a sewn, long-sleeved garment that extended to the knees and was belted with a belt, while the owner's weapons were fastened to the belt (sword or dagger, gorytos, battle-axe, whetstone etc.). Based on numerous archeological findings, men and warrior women wore long-sleeved tunics that were always belted, often with richly ornamented belts. The Kazakhstan Saka (e.g. Issyk Golden Man/Maiden) wore shorter and closer-fitting tunics than the Pontic steppe Scythians. Some Pazyryk culture Saka wore short belted tunic with a lapel on the right side, with upright collar, 'puffed' sleeves narrowing at the wrist and bound in narrow cuffs of a color different from the rest of the tunic.

Men and women wore coats: e.g. Pazyryk Saka had many varieties, from fur to felt. They could have worn a riding coat that later was known as a Median robe or Kantus. Long sleeved, and open, it seems that on the Persepolis Apadana Skudrian delegation is perhaps shown wearing such coat. The Pazyryk felt tapestry shows a rider wearing a billowing cloak.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |