| SILK ROAD

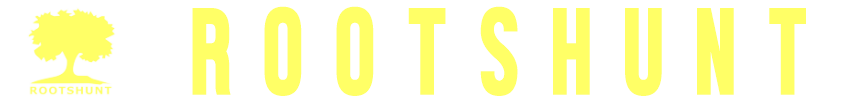

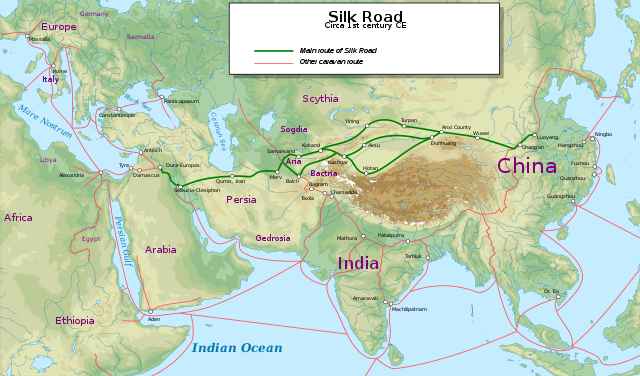

Main routes of the Silk Road

Route information

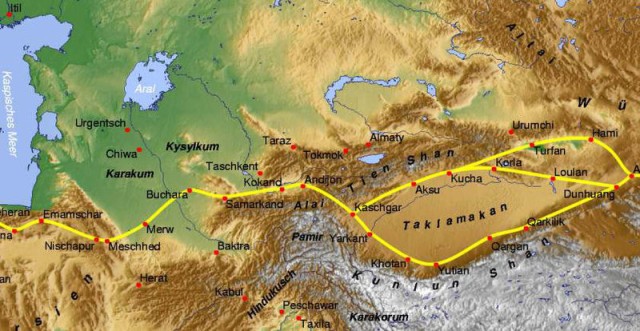

The Silk Road was a network of trade routes which connected the East and West, and was central to the economic, cultural, political, and religious interactions between these regions from the 2nd century BCE to the 18th century. The Silk Road primarily refers to the land routes connecting East Asia and Southeast Asia with South Asia, Persia, the Arabian Peninsula, East Africa and Southern Europe.

The Silk Road derives its name from the lucrative trade in silk carried out along its length, beginning in the Han dynasty in China (207 BCE–220 CE). The Han dynasty expanded the Central Asian section of the trade routes around 114 BCE through the missions and explorations of the Chinese imperial envoy Zhang Qian, as well as several military conquests. The Chinese took great interest in the security of their trade products, and extended the Great Wall of China to ensure the protection of the trade route.

The Silk Road trade played a significant role in the development of the civilizations of China, Korea, Japan, the Indian subcontinent, Iran, Europe, the Horn of Africa and Arabia, opening long-distance political and economic relations between the civilizations. Though silk was the major trade item exported from China, many other goods and ideas were exchanged, including religions (especially Buddhism), syncretic philosophies, sciences, and technologies like paper and gunpowder. So in addition to economic trade, the Silk Road was a route for cultural trade among the civilizations along its network. Diseases, most notably plague, also spread along the Silk Road.

In June 2014, UNESCO designated the Chang'an-Tianshan corridor of the Silk Road as a World Heritage Site. The Indian portion is on the tentative site list.

Name :

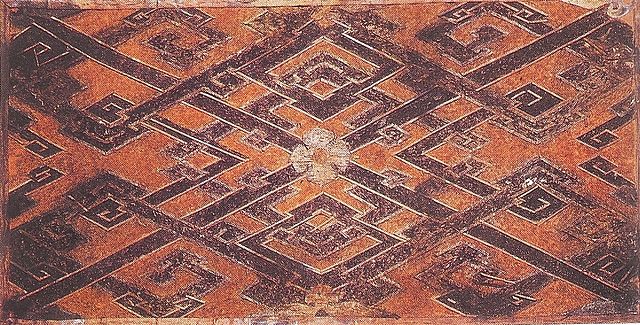

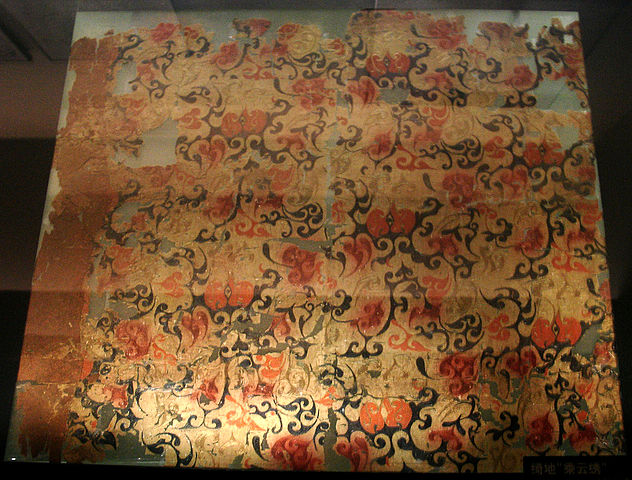

Woven silk textile from Tomb No. 1 at Mawangdui, Changsha, Hunan province, China, dated to the Western Han Era, 2nd century BCE The Silk Road derives its name from the lucrative silk, first developed in China and a major reason for the connection of trade routes into an extensive transcontinental network. It derives from the German term Seidenstraße (literally "Silk Road") and was first popularized by in 1877 by Ferdinand von Richthofen, who made seven expeditions to China from 1868 to 1872. However, the term itself has been in use in decades prior. The alternative translation "Silk Route" is also used occasionally. Although the term was coined in the 19th century, it did not gain widespread acceptance in academia or popularity among the public until the 20th century. The first book entitled The Silk Road was by Swedish geographer Sven Hedin in 1938.

Use of the term 'Silk Road' is not without its detractors. For instance, Warwick Ball contends that the maritime spice trade with India and Arabia was far more consequential for the economy of the Roman Empire than the silk trade with China, which at sea was conducted mostly through India and on land was handled by numerous intermediaries such as the Sogdians. Going as far as to call the whole thing a "myth" of modern academia, Ball argues that there was no coherent overland trade system and no free movement of goods from East Asia to the West until the period of the Mongol Empire. He notes that traditional authors discussing East-West trade such as Marco Polo and Edward Gibbon never labelled any route a "silk" one in particular.

The southern stretches of the Silk Road, from Khotan (Xinjiang) to Eastern China, were first used for jade and not silk, as long as 5000 BCE, and is still in use for this purpose. The term "Jade Road" would have been more appropriate than "Silk Road" had it not been for the far larger and geographically wider nature of the silk trade; the term is in current use in China.

Precursors

:

Chinese jade and steatite plaques, in the Scythian-style animal art of the steppes. 4th – 3rd century BCE. British Museum Central Eurasia has been known from ancient times for its horse riding and horse breeding communities, and the overland Steppe Route across the northern steppes of Central Eurasia was in use long before that of the Silk Road. Archeological sites such as the Berel burial ground in Kazakhstan, confirmed that the nomadic Arimaspians were not only breeding horses for trade but also produced great craftsmen able to propagate exquisite art pieces along the Silk Road. From the 2nd millennium BCE, nephrite jade was being traded from mines in the region of Yarkand and Khotan to China. Significantly, these mines were not very far from the lapis lazuli and spinel ("Balas Ruby") mines in Badakhshan, and, although separated by the formidable Pamir Mountains, routes across them were apparently in use from very early times.[citation needed]

Some remnants of what was probably Chinese silk dating from 1070 BCE have been found in Ancient Egypt. The Great Oasis cities of Central Asia played a crucial role in the effective functioning of the Silk Road trade. The originating source seems sufficiently reliable, but silk degrades very rapidly, so it cannot be verified whether it was cultivated silk (which almost certainly came from China) or a type of wild silk, which might have come from the Mediterranean or Middle East.

Following contacts between Metropolitan China and nomadic western border territories in the 8th century BCE, gold was introduced from Central Asia, and Chinese jade carvers began to make imitation designs of the steppes, adopting the Scythian-style animal art of the steppes (depictions of animals locked in combat). This style is particularly reflected in the rectangular belt plaques made of gold and bronze, with other versions in jade and steatite. [citation needed] An elite burial near Stuttgart, Germany, dated to the 6th century BCE, was excavated and found to have not only Greek bronzes but also Chinese silks. Similar animal-shaped pieces of art and wrestler motifs on belts have been found in Scythian grave sites stretching from the Black Sea region all the way to Warring States era archaeological sites in Inner Mongolia (at Aluchaideng) and Shaanxi (at Keshengzhuang) in China.

The expansion of Scythian cultures, stretching from the Hungarian plain and the Carpathian Mountains to the Chinese Kansu Corridor, and linking the Middle East with Northern India and the Punjab, undoubtedly played an important role in the development of the Silk Road. Scythians accompanied the Assyrian Esarhaddon on his invasion of Egypt, and their distinctive triangular arrowheads have been found as far south as Aswan. These nomadic peoples were dependent upon neighbouring settled populations for a number of important technologies, and in addition to raiding vulnerable settlements for these commodities, they also encouraged long-distance merchants as a source of income through the enforced payment of tariffs. Sogdians played a major role in facilitating trade between China and Central Asia along the Silk Roads as late as the 10th century, their language serving as a lingua franca for Asian trade as far back as the 4th century.

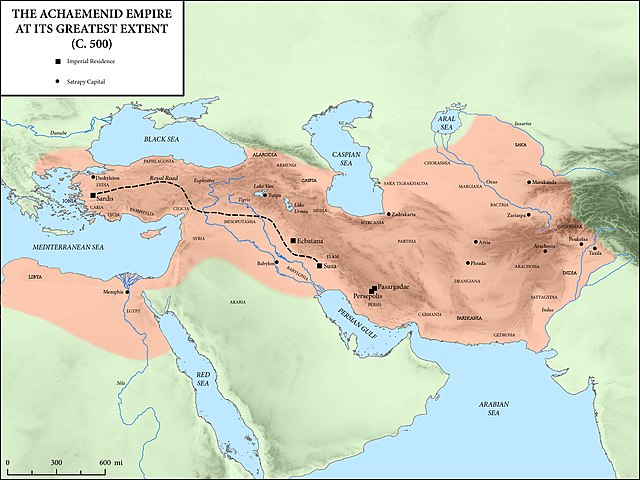

Persian Royal Road (500–330 BCE) :

Achaemenid Persian Empire at its greatest extent, showing the Royal Road By the time of Herodotus (c. 475 BCE), the Royal Road of the Persian Empire ran some 2,857 km (1,775 mi) from the city of Susa on the Karun (250 km (155 mi) east of the Tigris) to the port of Smyrna (modern Izmir in Turkey) on the Aegean Sea. It was maintained and protected by the Achaemenid Empire (c. 500–330 BCE) and had postal stations and relays at regular intervals. By having fresh horses and riders ready at each relay, royal couriers could carry messages and traverse the length of the road in nine days, while normal travelers took about three months.[citation needed]

Expansion of the Greek Empire (329 BCE–10 CE) :

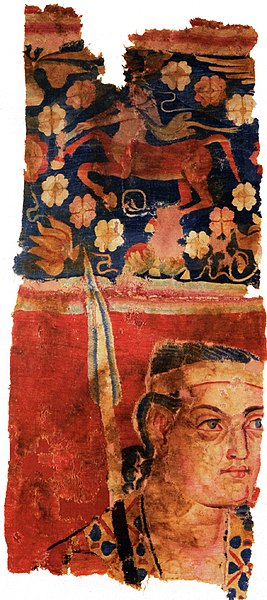

Soldier with a centaur in the Sampul tapestry, wool wall hanging, 3rd–2nd century BCE, Sampul, Urumqi Xinjiang Museum, China The next major step toward the development of the Silk Road was the expansion of the Macedonian empire of Alexander the Great into Central Asia. In August 329 BCE, at the mouth of the Fergana Valley, he founded the city of Alexandria Eschate or "Alexandria The Furthest".

The Greeks remained in Central Asia for the next three centuries, first through the administration of the Seleucid Empire, and then with the establishment of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom (250–125 BCE) in Bactria (modern Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Pakistan) and the later Indo-Greek Kingdom (180 BCE – 10 CE) in modern Northern Pakistan and Afghanistan. They continued to expand eastward, especially during the reign of Euthydemus (230–200 BCE), who extended his control beyond Alexandria Eschate to Sogdiana. There are indications that he may have led expeditions as far as Kashgar on the western edge of the Taklamakan Desert, leading to the first known contacts between China and the West around 200 BCE. [citation needed] The Greek historian Strabo writes, "they extended their empire even as far as the Seres (China) and the Phryni."

Classical Greek philosophy syncretised with Indian philosophy.

Initiation

in China (130 BCE) :

With the Mediterranean linked to the Fergana Valley, the next step was to open a route across the Tarim Basin and the Hexi Corridor to China Proper. This extension came around 130 BCE, with the embassies of the Han dynasty to Central Asia following the reports of the ambassador Zhang Qian (who was originally sent to obtain an alliance with the Yuezhi against the Xiongnu). Zhang Qian visited directly the kingdom of Dayuan in Ferghana, the territories of the Yuezhi in Transoxiana, the Bactrian country of Daxia with its remnants of Greco-Bactrian rule, and Kangju. He also made reports on neighbouring countries that he did not visit, such as Anxi (Parthia), Tiaozhi (Mesopotamia), Shendu (Indian subcontinent) and the Wusun. Zhang Qian's report suggested the economic reason for Chinese expansion and wall-building westward, and trail-blazed the Silk road, making it one of the most famous trade routes in history and in the world.

After winning the War of the Heavenly Horses and the Han–Xiongnu War, Chinese armies established themselves in Central Asia, initiating the Silk Route as a major avenue of international trade. Some say that the Chinese Emperor Wu became interested in developing commercial relationships with the sophisticated urban civilizations of Ferghana, Bactria, and the Parthian Empire: "The Son of Heaven on hearing all this reasoned thus: Ferghana (Dayuan "Great Ionians") and the possessions of Bactria (Ta-Hsia) and Parthian Empire (Anxi) are large countries, full of rare things, with a population living in fixed abodes and given to occupations somewhat identical with those of the Chinese people, but with weak armies, and placing great value on the rich produce of China" (Hou Hanshu, Later Han History). Others say that Emperor Wu was mainly interested in fighting the Xiongnu and that major trade began only after the Chinese pacified the Hexi Corridor. The Silk Roads' origin lay in the hands of the Chinese. The soil in China lacked Selenium, a deficiency which contributed to muscular weakness and reduced growth in horses. Consequently, horses in China were too frail to support the weight of a Chinese soldier. The Chinese needed the superior horses that nomads bred on the Eurasian steppes, and nomads wanted things only agricultural societies produced, such as grain and silk. Even after the construction of the Great Wall, nomads gathered at the gates of the wall to exchange. Soldiers sent to guard the wall were often paid in silk which they traded with the nomads. Past its inception, the Chinese continued to dominate the Silk Roads, a process which was accelerated when "China snatched control of the Silk Road from the Hsiung-nu" and the Chinese general Cheng Ki "installed himself as protector of the Tarim at Wu-lei, situated between Kara Shahr and Kuch." "China's control of the Silk Road at the time of the later Han, by ensuring the freedom of transcontinental trade along the double chain of oases north and south of the Tarim, favoured the dissemination of Buddhism in the river basin, and with it Indian literature and Hellenistic art."

A ceramic horse head and neck (broken from the body), from the Chinese Eastern Han dynasty (1st–2nd century CE)

Bronze coin of Constantius II (337–361), found in Karghalik, Xinjiang, China The Chinese were also strongly attracted by the tall and powerful horses (named "Heavenly horses") in the possession of the Dayuan (literally the "Great Ionians", the Greek kingdoms of Central Asia), which were of capital importance in fighting the nomadic Xiongnu. They defeated the Dayuan in the Han-Dayuan war. The Chinese subsequently sent numerous embassies, around ten every year, to these countries and as far as Seleucid Syria.

"Thus more embassies were dispatched to Anxi [Parthia], Yancai [who later joined the Alans], Lijian [Syria under the Greek Seleucids], Tiaozhi (Mesopotamia), and Tianzhu [northwestern India]... As a rule, rather more than ten such missions went forward in the course of a year, and at the least five or six." (Hou Hanshu, Later Han History).

These connections marked the beginning of the Silk Road trade network that extended to the Roman Empire. The Chinese campaigned in Central Asia on several occasions, and direct encounters between Han troops and Roman legionaries (probably captured or recruited as mercenaries by the Xiong Nu) are recorded, particularly in the 36 BCE battle of Sogdiana (Joseph Needham, Sidney Shapiro). It has been suggested that the Chinese crossbow was transmitted to the Roman world on such occasions, although the Greek gastraphetes provides an alternative origin. R. Ernest Dupuy and Trevor N. Dupuy suggest that in 36 BCE.

"Han expedition into Central Asia, west of Jaxartes River, apparently encountered and defeated a contingent of Roman legionaries. The Romans may have been part of Antony's army invading Parthia. Sogdiana (modern Bukhara), east of the Oxus River, on the Polytimetus River, was apparently the most easterly penetration ever made by Roman forces in Asia. The margin of Chinese victory appears to have been their crossbows, whose bolts and darts seem easily to have penetrated Roman shields and armour."

The

Roman historian Florus also describes the visit of numerous envoys,

which included Seres(China), to the first Roman Emperor Augustus,

who reigned between 27 BCE and 14 CE:

—

Henry Yule, Cathay and the Way Thither (1866)

A maritime Silk Route opened up between Chinese-controlled Giao ChI (centred in modern Vietnam, near Hanoi), probably by the 1st century. It extended, via ports on the coasts of India and Sri Lanka, all the way to Roman-controlled ports in Roman Egypt and the Nabataean territories on the northeastern coast of the Red Sea. The earliest Roman glassware bowl found in China was unearthed from a Western Han tomb in Guangzhou, dated to the early 1st century BCE, indicating that Roman commercial items were being imported through the South China Sea. According to Chinese dynastic histories, it is from this region that the Roman embassies arrived in China, beginning in 166 CE during the reigns of Marcus Aurelius and Emperor Huan of Han. Other Roman glasswares have been found in Eastern-Han-era tombs (25–220 CE) more further inland in Nanjing and Luoyang.

P.O. Harper asserts that a 2nd or 3rd-century Roman gilt silver plate found in Jingyuan, Gansu, China with a central image of the Greco-Roman god Dionysus resting on a feline creature, most likely came via Greater Iran (i.e. Sogdiana). Valerie Hansen (2012) believed that earliest Roman coins found in China date to the 4th century, during Late Antiquity and the Dominate period, and come from the Byzantine Empire. However, Warwick Ball (2016) highlights the recent discovery of sixteen Principate-era Roman coins found in Xi'an (formerly Chang'an, one of the two Han capitals) that were minted during the reigns of Roman emperors spanning from Tiberius to Aurelian (i.e. 1st to 3rd centuries CE).

Helen Wang points out that although these coins were found in China, they were deposited there in the twentieth century, not in ancient times, and therefore do not shed light on historic contacts between China and Rome. Roman golden medallions made during the reign of Antoninus Pius and quite possibly his successor Marcus Aurelius have been found at Óc Eo in southern Vietnam, which was then part of the Kingdom of Funan bordering the Chinese province of Jiaozhi in northern Vietnam. Given the archaeological finds of Mediterranean artefacts made by Louis Malleret in the 1940s, Óc Eo may have been the same site as the port city of Kattigara described by Ptolemy in his Geography (c. 150 CE), although Ferdinand von Richthofen had previously believed it was closer to Hanoi.

Evolution

:

Central Asia during Roman times, with the first Silk Road Soon after the Roman conquest of Egypt in 30 BCE, regular communications and trade between China, Southeast Asia, India, the Middle East, Africa, and Europe blossomed on an unprecedented scale. The Roman Empire inherited eastern trade routes that were part of the Silk Road from the earlier Hellenistic powers and the Arabs. With control of these trade routes, citizens of the Roman Empire received new luxuries and greater prosperity for the Empire as a whole. The Roman-style glassware discovered in the archeological sites of Gyeongju, capital of the Silla kingdom (Korea) showed that Roman artifacts were traded as far as the Korean peninsula.

The Greco-Roman trade with India started by Eudoxus of Cyzicus in 130 BCE continued to increase, and according to Strabo (II.5.12), by the time of Augustus, up to 120 ships were setting sail every year from Myos Hormos in Roman Egypt to India. The Roman Empire connected with the Central Asian Silk Road through their ports in Barygaza (known today as Bharuch) and Barbaricum (known today as the city of Karachi, Sindh, Pakistan) and continued along the western coast of India. An ancient "travel guide" to this Indian Ocean trade route was the Greek Periplus of the Erythraean Sea written in 60 CE.

The travelling party of Maës Titianus penetrated farthest east along the Silk Road from the Mediterranean world, probably with the aim of regularising contacts and reducing the role of middlemen, during one of the lulls in Rome's intermittent wars with Parthia, which repeatedly obstructed movement along the Silk Road. Intercontinental trade and communication became regular, organised, and protected by the "Great Powers". Intense trade with the Roman Empire soon followed, confirmed by the Roman craze for Chinese silk (supplied through the Parthians), even though the Romans thought silk was obtained from trees. This belief was affirmed by Seneca the Younger in his Phaedra and by Virgil in his Georgics. Notably, Pliny the Elder knew better. Speaking of the bombyx or silk moth, he wrote in his Natural Histories "They weave webs, like spiders, that become a luxurious clothing material for women, called silk." The Romans traded spices, glassware, perfumes, and silk.

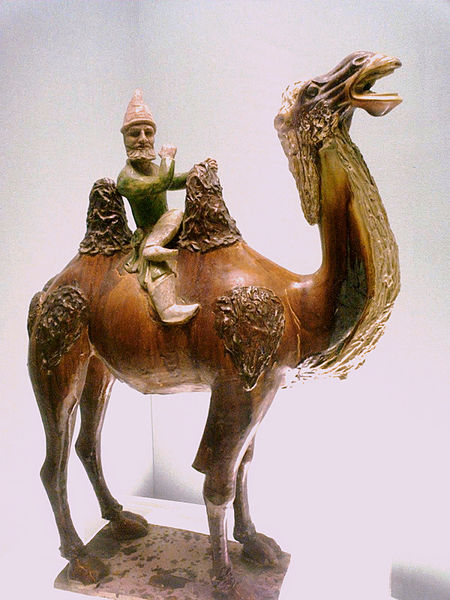

A Westerner on a camel, Northern Wei dynasty (386–534) Roman artisans began to replace yarn with valuable plain silk cloths from China and the Silla Kingdom in Gyeongju, Korea. Chinese wealth grew as they delivered silk and other luxury goods to the Roman Empire, whose wealthy women admired their beauty. The Roman Senate issued, in vain, several edicts to prohibit the wearing of silk, on economic and moral grounds: the import of Chinese silk caused a huge outflow of gold, and silk clothes were considered decadent and immoral.

I can see clothes of silk, if materials that do not hide the body, nor even one's decency, can be called clothes.... Wretched flocks of maids labour so that the adulteress may be visible through her thin dress, so that her husband has no more acquaintance than any outsider or foreigner with his wife's body.

The West Roman Empire, and its demand for sophisticated Asian products, crumbled in the West around the 5th century.

The unification of Central Asia and Northern India within the Kushan Empire in the 1st to 3rd centuries reinforced the role of the powerful merchants from Bactria and Taxila. They fostered multi-cultural interaction as indicated by their 2nd century treasure hoards filled with products from the Greco-Roman world, China, and India, such as in the archeological site of Begram.

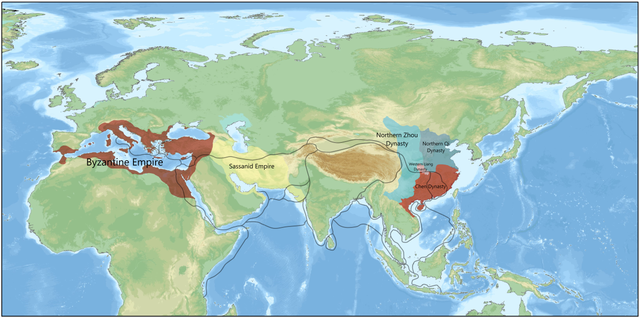

Byzantine Empire (6th–14th centuries) :

Byzantine Greek historian Procopius stated that two Nestorian Christian monks eventually uncovered the way silk was made. From this revelation, monks were sent by the Byzantine Emperor Justinian (ruled 527–565) as spies on the Silk Road from Constantinople to China and back to steal the silkworm eggs, resulting in silk production in the Mediterranean, particularly in Thrace in northern Greece, and giving the Byzantine Empire a monopoly on silk production in medieval Europe. In 568 the Byzantine ruler Justin II was greeted by a Sogdian embassy representing Istämi, ruler of the First Turkic Khaganate, who formed an alliance with the Byzantines against Khosrow I of the Sasanian Empire that allowed the Byzantines to bypass the Sasanian merchants and trade directly with the Sogdians for purchasing Chinese silk. Although the Byzantines had already procured silkworm eggs from China by this point, the quality of Chinese silk was still far greater than anything produced in the West, a fact that is perhaps emphasized by the discovery of coins minted by Justin II found in a Chinese tomb of Shanxi province dated to the Sui dynasty (581–618).

Coin of Constans II (r. 641–648), who is named in Chinese sources as the first of several Byzantine emperors to send embassies to the Chinese Tang dynasty Both the Old Book of Tang and New Book of Tang, covering the history of the Chinese Tang dynasty (618–907), record that a new state called Fu-lin (Byzantine Empire) was virtually identical to the previous Daqin (Roman Empire). Several Fu-lin embassies were recorded for the Tang period, starting in 643 with an alleged embassy by Constans II (transliterated as Bo duo li, from his nickname "Konstantinos Pogonatos") to the court of Emperor Taizong of Tang. The History of Song describes the final embassy and its arrival in 1081, apparently sent by Michael VII Doukas (transliterated as Mie li sha ling kai sa, from his name and title Michael VII Parapinakes Caesar) to the court of Emperor Shenzong of the Song dynasty (960–1279). However, the History of Yuan claims that a Byzantine man became a leading astronomer and physician in Khanbaliq, at the court of Kublai Khan, Mongol founder of the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) and was even granted the noble title 'Prince of Fu lin' (Chinese: Fú lin wáng). The Uyghur Nestorian Christian diplomat Rabban Bar Sauma, who set out from his Chinese home in Khanbaliq (Beijing) and acted as a representative for Arghun (a grandnephew of Kublai Khan), traveled throughout Europe and attempted to secure military alliances with Edward I of England, Philip IV of France, Pope Nicholas IV, as well as the Byzantine ruler Andronikos II Palaiologos. Andronikos II had two half-sisters who were married to great-grandsons of Genghis Khan, which made him an in-law with the Yuan-dynasty Mongol ruler in Beijing, Kublai Khan. The History of Ming preserves an account where the Hongwu Emperor, after founding the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), had a supposed Byzantine merchant named Nieh-ku-lun deliver his proclamation about the establishment of a new dynasty to the Byzantine court of John V Palaiologos in September 1371. Friedrich Hirth (1885), Emil Bretschneider (1888), and more recently Edward Luttwak (2009) presumed that this was none other than Nicolaus de Bentra, a Roman Catholic bishop of Khanbilaq chosen by Pope John XXII to replace the previous archbishop John of Montecorvino.

Tang dynasty (7th century) :

A Chinese sancai statue of a Sogdian man with a wineskin, Tang dynasty (618–907)

After the Tang defeated the Gokturks, they reopened the Silk Road to the west Although the Silk Road was initially formulated during the reign of Emperor Wu of Han (141–87 BCE), it was reopened by the Tang Empire in 639 when Hou Junji conquered the Western Regions, and remained open for almost four decades. It was closed after the Tibetans captured it in 678, but in 699, during Empress Wu's period, the Silk Road reopened when the Tang reconquered the Four Garrisons of Anxi originally installed in 640, once again connecting China directly to the West for land-based trade. The Tang captured the vital route through the Gilgit Valley from Tibet in 722, lost it to the Tibetans in 737, and regained it under the command of the Goguryeo-Korean General Gao Xianzhi.

While the Turks were settled in the Ordos region (former territory of the Xiongnu), the Tang government took on the military policy of dominating the central steppe. The Tang dynasty (along with Turkic allies) conquered and subdued Central Asia during the 640s and 650s. During Emperor Taizong's reign alone, large campaigns were launched against not only the Göktürks, but also separate campaigns against the Tuyuhun, the oasis states, and the Xueyantuo. Under Emperor Taizong, Tang general Li Jing conquered the Eastern Turkic Khaganate. Under Emperor Gaozong, Tang general Su Dingfang conquered the Western Turkic Khaganate, which was an important ally of Byzantine empire. After these conquests, the Tang dynasty fully controlled the Xiyu, which was the strategic location astride the Silk Road. This led the Tang dynasty to reopen the Silk Road.

The Tang dynasty established a second Pax Sinica, and the Silk Road reached its golden age, whereby Persian and Sogdian merchants benefited from the commerce between East and West. At the same time, the Chinese empire welcomed foreign cultures, making it very cosmopolitan in its urban centres. In addition to the land route, the Tang dynasty also developed the maritime Silk Route. Chinese envoys had been sailing through the Indian Ocean to India since perhaps the 2nd century BCE, yet it was during the Tang dynasty that a strong Chinese maritime presence could be found in the Persian Gulf and Red Sea into Persia, Mesopotamia (sailing up the Euphrates River in modern-day Iraq), Arabia, Egypt, Aksum (Ethiopia), and Somalia in the Horn of Africa.

Sogdian-Türkic tribes (4th–8th centuries) :

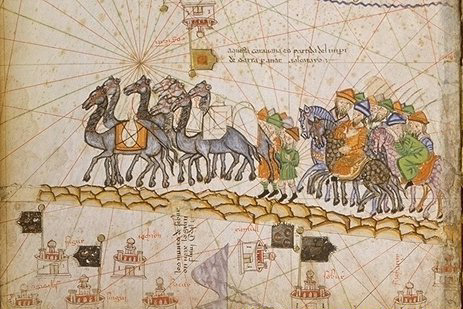

Marco Polo's caravan on the Silk Road, 1380 The Silk Road represents an early phenomenon of political and cultural integration due to inter-regional trade. In its heyday, it sustained an international culture that strung together groups as diverse as the Magyars, Armenians, and Chinese. The Silk Road reached its peak in the west during the time of the Byzantine Empire; in the Nile-Oxus section, from the Sassanid Empire period to the Il Khanate period; and in the sinitic zone from the Three Kingdoms period to the Yuan dynasty period. Trade between East and West also developed across the Indian Ocean, between Alexandria in Egypt and Guangzhou in China. Persian Sassanid coins emerged as a means of currency, just as valuable as silk yarn and textiles.

Under its strong integrating dynamics on the one hand and the impacts of change it transmitted on the other, tribal societies previously living in isolation along the Silk Road, and pastoralists who were of barbarian cultural development, were drawn to the riches and opportunities of the civilisations connected by the routes, taking on the trades of marauders or mercenaries. [citation needed] "Many barbarian tribes became skilled warriors able to conquer rich cities and fertile lands and to forge strong military empires."

Map of Eurasia and Africa showing trade networks, c. 870 The Sogdians dominated the East-West trade after the 4th century up to the 8th century, with Suyab and Talas ranking among their main centres in the north. They were the main caravan merchants of Central Asia. Their commercial interests were protected by the resurgent military power of the Göktürks, whose empire has been described as "the joint enterprise of the Ashina clan and the Soghdians". A.V. Dybo noted that "according to historians, the main driving force of the Great Silk Road were not just Sogdians, but the carriers of a mixed Sogdian-Türkic culture that often came from mixed families."

Their trade, with some interruptions, continued in the 9th century within the framework of the Uighur Empire, which until 840 extended across northern Central Asia and obtained from China enormous deliveries of silk in exchange for horses. At this time caravans of Sogdians traveling to Upper Mongolia are mentioned in Chinese sources. They played an equally important religious and cultural role. Part of the data about eastern Asia provided by Muslim geographers of the 10th century actually goes back to Sogdian data of the period 750–840 and thus shows the survival of links between east and west. However, after the end of the Uighur Empire, Sogdian trade went through a crisis. What mainly issued from Muslim Central Asia was the trade of the Samanids, which resumed the northwestern road leading to the Khazars and the Urals and the northeastern one toward the nearby Turkic tribes.

The Silk Road gave rise to the clusters of military states of nomadic origins in North China, ushered the Nestorian, Manichaean, Buddhist, and later Islamic religions into Central Asia and China.

Islamic era (8th–13th centuries) :

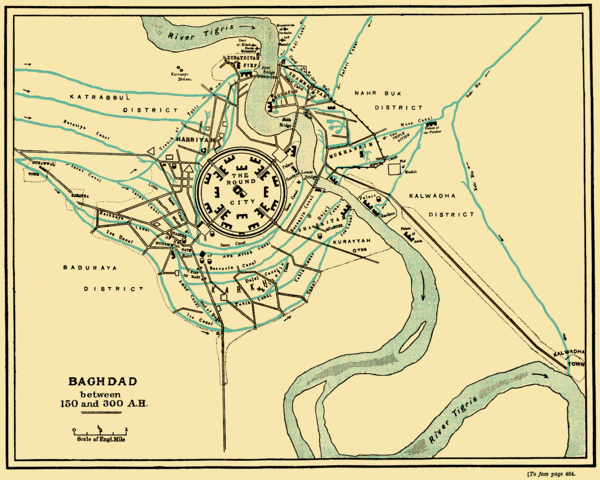

A lion motif on Sogdian polychrome silk, 8th century, most likely from Bukhara By the Umayyad era, Damascus had overtaken Ctesiphon as a major trade center until the Abbasid dynasty built the city of Baghdad, which became the most important city along the silk road.

At the end of its glory, the routes brought about the largest continental empire ever, the Mongol Empire, with its political centres strung along the Silk Road (Beijing in North China, Karakorum in central Mongolia, Sarmakhand in Transoxiana, Tabriz in Northern Iran, realising the political unification of zones previously loosely and intermittently connected by material and cultural goods.[citation needed]

The Islamic world expanded into Central Asia during the 8th century, under the Umayyad Caliphate, while its successor the Abbasid Caliphate put a halt to Chinese westward expansion at the Battle of Talas in 751 (near the Talas River in modern-day Kyrgyzstan). However, following the disastrous An Lushan Rebellion (755–763) and the conquest of the Western Regions by the Tibetan Empire, the Tang Empire was unable to reassert its control over Central Asia. Contemporary Tang authors noted how the dynasty had gone into decline after this point. In 848 the Tang Chinese, led by the commander Zhang Yichao, were only able to reclaim the Hexi Corridor and Dunhuang in Gansu from the Tibetans. The Persian Samanid Empire (819–999) centered in Bukhara (Uzbekistan) continued the trade legacy of the Sogdians. The disruptions of trade were curtailed in that part of the world by the end of the 10th century and conquests of Central Asia by the Turkic Islamic Kara-Khanid Khanate, yet Nestorian Christianity, Zoroastrianism, Manichaeism, and Buddhism in Central Asia virtually disappeared.

During the early 13th century Khwarezmia was invaded by the Mongol Empire. The Mongol ruler Genghis Khan had the once vibrant cities of Bukhara and Samarkand burned to the ground after besieging them. However, in 1370 Samarkand saw a revival as the capital of the new Timurid Empire. The Turko-Mongol ruler Timur forcefully moved artisans and intellectuals from across Asia to Samarkand, making it one of the most important trade centers and cultural entrepôts of the Islamic world.

Mongol empire (13th–14th centuries) :

The Mongol expansion throughout the Asian continent from around 1207 to 1360 helped bring political stability and re-established the Silk Road (via Karakorum and Khanbaliq). It also brought an end to the dominance of the Islamic Caliphate over world trade. Because the Mongols came to control the trade routes, trade circulated throughout the region, though they never abandoned their nomadic lifestyle.

The Mongol rulers wanted to establish their capital on the Central Asian steppe, so to accomplish this goal, after every conquest they enlisted local people (traders, scholars, artisans) to help them construct and manage their empire. The Mongols developed overland and maritime routes throughout the Eurasian continent, Black Sea and Mediterranean in the west and Indian Ocean in the south. In the second half of the thirteenth century Mongol-sponsored business partnerships flourished in the Indian Ocean connecting Mongol Middle East and Mongol China.

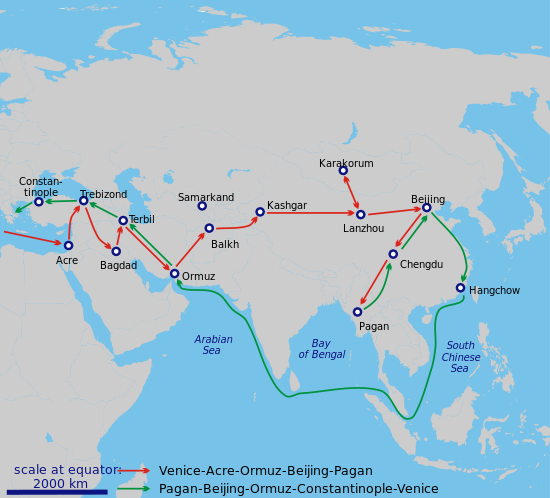

The Mongol diplomat Rabban Bar Sauma visited the courts of Europe in 1287–88 and provided a detailed written report to the Mongols. Around the same time, the Venetian explorer Marco Polo became one of the first Europeans to travel the Silk Road to China. His tales, documented in The Travels of Marco Polo, opened Western eyes to some of the customs of the Far East. He was not the first to bring back stories, but he was one of the most widely read. He had been preceded by numerous Christian missionaries to the East, such as William of Rubruck, Benedykt Polak, Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, and Andrew of Longjumeau. Later envoys included Odoric of Pordenone, Giovanni de' Marignolli, John of Montecorvino, Niccolò de' Conti, and Ibn Battuta, a Moroccan Muslim traveller who passed through the present-day Middle East and across the Silk Road from Tabriz between 1325–1354.

In the 13th century efforts were made at forming a Franco-Mongol alliance, with an exchange of ambassadors and (failed) attempts at military collaboration in the Holy Land during the later Crusades. Eventually the Mongols in the Ilkhanate, after they had destroyed the Abbasid and Ayyubid dynasties, converted to Islam and signed the 1323 Treaty of Aleppo with the surviving Muslim power, the Egyptian Mamluks.[citation needed]

Some studies indicate that the Black Death, which devastated Europe starting in the late 1340s, may have reached Europe from Central Asia (or China) along the trade routes of the Mongol Empire. One theory holds that Genoese traders coming from the entrepot of Trebizond in northern Turkey carried the disease to Western Europe; like many other outbreaks of plague, there is strong evidence that it originated in marmots in Central Asia and was carried westwards to the Black Sea by Silk Road traders.

Decline and disintegration (15th century) :

This section needs additional citations for verification.

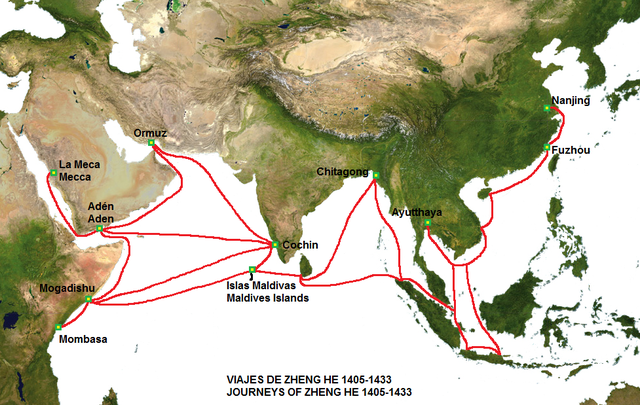

Port cities on the maritime silk route featured on the voyages of Zheng He The fragmentation of the Mongol Empire loosened the political, cultural, and economic unity of the Silk Road. Turkmeni marching lords seized land around the western part of the Silk Road from the decaying Byzantine Empire. After the fall of the Mongol Empire, the great political powers along the Silk Road became economically and culturally separated. Accompanying the crystallisation of regional states was the decline of nomad power, partly due to the devastation of the Black Death and partly due to the encroachment of sedentary civilisations equipped with gunpowder.

Partial

Revival in West Asia :

Collapse

(18th century) :

New Silk Road (20th - 21st centuries) :

A silk banner from Mawangdui, Changsha, Hunan province; it was draped over the coffin of Lady Dai (d. 168 BCE), wife of the Marquess Li Cang (d. 186 BCE), chancellor for the Kingdom of Changsha.

Railway

(1990) :

Belt

and Road Initiative (2013) :

On 15 February 2016, with a change in routing, the first train dispatched under the scheme arrived from eastern Zhejiang Province to Tehran. Though this section does not complete the Silk Road–style overland connection between China and Europe, but new railway line connecting China to Europe via Istanbul's has now been established. The actual route went through Almaty, Bishkek, Samarkand, and Dushanbe.

Routes

:

Northern route :

The northern route started at Chang'an (now called Xi'an), an ancient capital of China that was moved further east during the Later Han to Luoyang. The route was defined around the 1st century BCE when Han Wudi put an end to harassment by nomadic tribes.[citation needed]

The northern route travelled northwest through the Chinese province of Gansu from Shaanxi Province and split into three further routes, two of them following the mountain ranges to the north and south of the Taklamakan Desert to rejoin at Kashgar, and the other going north of the Tian Shan mountains through Turpan, Talgar, and Almaty (in what is now southeast Kazakhstan). The routes split again west of Kashgar, with a southern branch heading down the Alai Valley towards Termez (in modern Uzbekistan) and Balkh (Afghanistan), while the other travelled through Kokand in the Fergana Valley (in present-day eastern Uzbekistan) and then west across the Karakum Desert. Both routes joined the main southern route before reaching ancient Merv, Turkmenistan. Another branch of the northern route turned northwest past the Aral Sea and north of the Caspian Sea, then and on to the Black Sea.

A route for caravans, the northern Silk Road brought to China many goods such as "dates, saffron powder and pistachio nuts from Persia; frankincense, aloes and myrrh from Somalia; sandalwood from India; glass bottles from Egypt, and other expensive and desirable goods from other parts of the world." In exchange, the caravans sent back bolts of silk brocade, lacquer-ware, and porcelain.

Southern

route :

Southwestern route :

The southwestern route is believed to be the Ganges/Brahmaputra Delta, which has been the subject of international interest for over two millennia. Strabo, the 1st-century Roman writer, mentions the deltaic lands: "Regarding merchants who now sail from Egypt...as far as the Ganges, they are only private citizens..." His comments are interesting as Roman beads and other materials are being found at Wari-Bateshwar ruins, the ancient city with roots from much earlier, before the Bronze Age, presently being slowly excavated beside the Old Brahmaputra in Bangladesh. Ptolemy's map of the Ganges Delta, a remarkably accurate effort, showed that his informants knew all about the course of the Brahmaputra River, crossing through the Himalayas then bending westward to its source in Tibet. It is doubtless that this delta was a major international trading center, almost certainly from much earlier than the Common Era. Gemstones and other merchandise from Thailand and Java were traded in the delta and through it. Chinese archaeological writer Bin Yang and some earlier writers and archaeologists, such as Janice Stargardt, strongly suggest this route of international trade as Sichuan–Yunnan–Burma–Bangladesh route. According to Bin Yang, especially from the 12th century the route was used to ship bullion from Yunnan (gold and silver are among the minerals in which Yunnan is rich), through northern Burma, into modern Bangladesh, making use of the ancient route, known as the 'Ledo' route. The emerging evidence of the ancient cities of Bangladesh, in particular Wari-Bateshwar ruins, Mahasthangarh, Bhitagarh, Bikrampur, Egarasindhur, and Sonargaon, are believed to be the international trade centers in this route.

Maritime

route :

The trade route encompassed numbers of bodies of waters; including South China Sea, Strait of Malacca, Indian Ocean, Gulf of Bengal, Arabian Sea, Persian Gulf and the Red Sea. The maritime route overlaps with historic Southeast Asian maritime trade, Spice trade, Indian Ocean trade and after 8th century – the Arabian naval trade network. The network also extend eastward to East China Sea and Yellow Sea to connect China with Korean Peninsula and Japanese archipelago.

Expansion of religions :

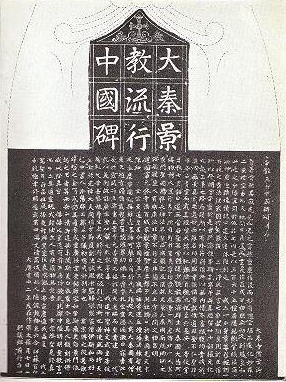

The Nestorian Stele, created in 781, describes the introduction of Nestorian Christianity to China Richard Foltz, Xinru Liu, and others have described how trading activities along the Silk Road over many centuries facilitated the transmission not just of goods but also ideas and culture, notably in the area of religions. Zoroastrianism, Judaism, Buddhism, Christianity, Manichaeism, and Islam all spread across Eurasia through trade networks that were tied to specific religious communities and their institutions. Notably, established Buddhist monasteries along the Silk Road offered a haven, as well as a new religion for foreigners.

The spread of religions and cultural traditions along the Silk Roads, according to Jerry H. Bentley, also led to syncretism. One example was the encounter with the Chinese and Xiongnu nomads. These unlikely events of cross-cultural contact allowed both cultures to adapt to each other as an alternative. The Xiongnu adopted Chinese agricultural techniques, dress style, and lifestyle, while the Chinese adopted Xiongnu military techniques, some dress style, music, and dance. Perhaps most surprising of the cultural exchanges between China and the Xiongnu, Chinese soldiers sometimes defected and converted to the Xiongnu way of life, and stayed in the steppes for fear of punishment.

Nomadic mobility played a key role in facilitating inter-regional contacts and cultural exchanges along the ancient Silk Roads.

Transmission

of Christianity :

Transmission of Buddhism :

Fragment of a wall painting depicting Buddh from a stup in Miran along the Silk Road (200 AD - 400 AD)

A blue-eyed Central Asian monk teaching an East-Asian monk, Bezeklik, Turfan, eastern Tarim Basin, China, 9th century; the monk on the right is possibly Tocharian, although more likely Sogdian The transmission of Buddhism to China via the Silk Road began in the 1st century CE, according to a semi-legendary account of an ambassador sent to the West by the Chinese Emperor Ming (58–75). During this period Buddhism began to spread throughout Southeast, East, and Central Asia. Mahayan, Theravad, and Tibetan Buddhism are the three primary forms of Buddhism that spread across Asia via the Silk Road.

The Buddhist movement was the first large-scale missionary movement in the history of world religions. Chinese missionaries were able to assimilate Buddhism, to an extent, to native Chinese Daoists, which brought the two beliefs together. Buddha's community of followers, the Sangha, consisted of male and female monks and laity. These people moved through India and beyond to spread the ideas of Buddha. As the number of members within the Sangha increased, it became costly so that only the larger cities were able to afford having the Buddha and his disciples visit. It is believed that under the control of the Kushans, Buddhism was spread to China and other parts of Asia from the middle of the first century to the middle of the third century. Extensive contacts started in the 2nd century, probably as a consequence of the expansion of the Kushan empire into the Chinese territory of the Tarim Basin, due to the missionary efforts of a great number of Buddhist monks to Chinese lands. The first missionaries and translators of Buddhists scriptures into Chinese were either Parthian, Kushan, Sogdian, or Kuchean.

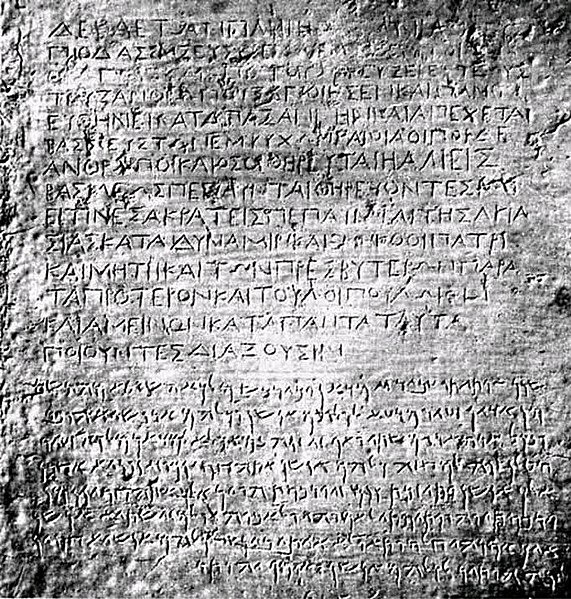

Bilingual edict (Greek and Aramaic) by Indian Buddhist King Ashok, 3rd century BCE; see Edicts of Ashoka, from Kandahar. This edict advocates the adoption of "godliness" using the Greek term Eusebeia for Dharma. Kabul Museum One result of the spread of Buddhism along the Silk Road was displacement and conflict. The Greek Seleucids were exiled to Iran and Central Asia because of a new Iranian dynasty called the Parthians at the beginning of the 2nd century BCE, and as a result the Parthians became the new middle men for trade in a period when the Romans were major customers for silk. Parthian scholars were involved in one of the first ever Buddhist text translations into the Chinese language. Its main trade centre on the Silk Road, the city of Merv, in due course and with the coming of age of Buddhism in China, became a major Buddhist centre by the middle of the 2nd century. Knowledge among people on the silk roads also increased when Emperor Ashoka of the Maurya dynasty (268–239 BCE) converted to Buddhism and raised the religion to official status in his northern Indian empire.

From the 4th century CE onward, Chinese pilgrims also started to travel on the Silk Road to India to get improved access to the original Buddhist scriptures, with Fa-hsien's pilgrimage to India (395–414), and later Xuanzang (629–644) and Hyecho, who traveled from Korea to India. The travels of the priest Xuanzang were fictionalized in the 16th century in a fantasy adventure novel called Journey to the West, which told of trials with demons and the aid given by various disciples on the journey.

A statue depicting Buddha giving a sermon, from Sarnath, 3,000 km (1,864 mi) southwest of Urumqi, Xinjiang, 8th century There were many different schools of Buddhism travelling on the Silk Road. The Dharmaguptakas and the Sarvastivadins were two of the major Nikaya schools. These were both eventually displaced by the Mahayana, also known as "Great Vehicle". This movement of Buddhism first gained influence in the Khotan region. The Mahayan, which was more of a "pan-Buddhist movement" than a school of Buddhism, appears to have begun in northwestern India or Central Asia. It formed during the 1st century BCE and was small at first, and the origins of this "Greater Vehicle" are not fully clear. Some Mahayana scripts were found in northern Pakistan, but the main texts are still believed to have been composed in Central Asia along the Silk Road. These different schools and movements of Buddhism were a result of the diverse and complex influences and beliefs on the Silk Road. With the rise of Mahayana Buddhism, the initial direction of Buddhist development changed. This form of Buddhism highlighted, as stated by Xinru Liu, "the elusiveness of physical reality, including material wealth." It also stressed getting rid of material desire to a certain point; this was often difficult for followers to understand.

During the 5th and 6th centuries CE, merchants played a large role in the spread of religion, in particular Buddhism. Merchants found the moral and ethical teachings of Buddhism an appealing alternative to previous religions. As a result, merchants supported Buddhist monasteries along the Silk Road, and in return the Buddhists gave the merchants somewhere to stay as they traveled from city to city. As a result, merchants spread Buddhism to foreign encounters as they traveled. Merchants also helped to establish diaspora within the communities they encountered, and over time their cultures became based on Buddhism. As a result, these communities became centers of literacy and culture with well-organized marketplaces, lodging, and storage. The voluntary conversion of Chinese ruling elites helped the spread of Buddhism in East Asia and led Buddhism to become widespread in Chinese society. The Silk Road transmission of Buddhism essentially ended around the 7th century with the rise of Islam in Central Asia.

Judaism

on the Silk Road :

During this time in the Persian Emby the penced ire, the Judean religion was influenced by the Iranian religion. Concepts of a paradise for the good and a place of suffering for the wicked, and a form or world ending apocalypse came from Iranian religious ideas, and this is supported by a lack of such ideas from pre-exile Judean sources. The origin of the devil is also said to come from the Iranian Angra Mainyu, an evil figure in Iranian mythology.

Expansion of the arts :

Many artistic influences were transmitted via the Silk Road, particularly through Central Asia, where Hellenistic, Iranian, Indian and Chinese influences could intermix. Greco-Buddhist art represents one of the most vivid examples of this interaction. Silk was also a representation of art, serving as a religious symbol. Most importantly, silk was used as currency for trade along the silk road.

These artistic influences can be seen in the development of Buddhism where, for instance, Buddh was first depicted as human in the Kushan period. Many scholars have attributed this to Greek influence. The mixture of Greek and Indian elements can be found in later Buddhist art in China and throughout countries on the Silk Road.

The production of art consisted of many different items that were traded along the Silk Roads from the East to the West. One common product, the lapis lazuli, was a blue stone with golden specks, which was used as paint after it was ground into powder.

Commemoration

:

To commemorate the Silk Road becoming a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the China National Silk Museum announced a "Silk Road Week" to take place 19-25 June 2020.

Bishkek and Almaty each have a major east-west street named after the Silk Road (Kyrgyz: Jibek Jolu in Bishkek, and Kazakh: Jibek Joly in Almaty). There is also a Silk Road in Macclesfield, UK.

Gallery :

Silk Road and artifacts

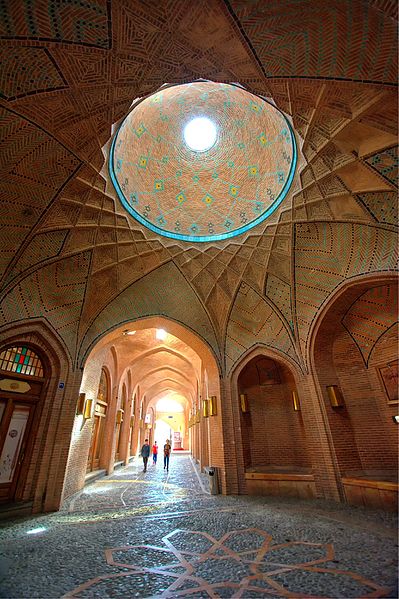

Caravanserai of Sa'd al-Saltaneh

Sultanhani caravanserai

Shaki Caravanserai, Shaki, Azerbaijan

Two-Storeyed Caravanserai, Baku, Azerbaijan

Bridge in Ani, capital of medieval Armenia

Taldyk pass

Medieval fortress of Amul, Turkmenabat, Turkmenistan

Zeinodin Caravanserai

Sogdian man on a Bactrian camel, sancai ceramic glaze, Chinese Tang dynasty (618–907)

The ruins of a Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) Chinese watchtower made of rammed earth at Dunhuang, Gansu province

A late Zhou or early Han Chinese bronze mirror inlaid with glass, perhaps incorporated Greco-Roman artistic patterns

A Chinese Western Han dynasty (202 BCE – 9 CE) bronze rhinoceros with gold and silver inlay

Han dynasty Granary west of Dunhuang on the Silk Road

Green Roman glass cup unearthed from an Eastern Han dynasty (25–220 CE) tomb, Guangxi, southern China Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)