| TURKIFICATION

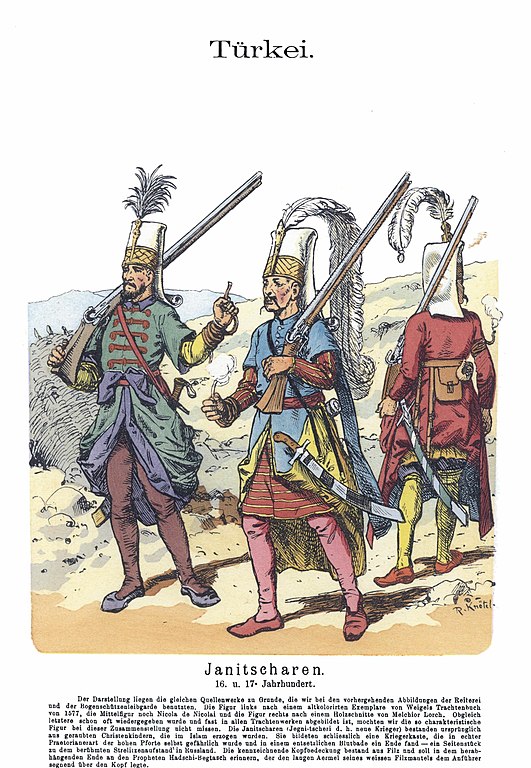

Janissaries in the Ottoman army were largely of Christian origin Turkification, or Turkicisation (Turkish: Türklestirme), describes both a cultural and language shift whereby populations or states adopted a historical Turkic culture, such as in the Ottoman Empire, and the Turkish nationalist policies of the Republic of Turkey toward ethnic minorities in Turkey. As the Turkic states developed and grew, there were many instances of this cultural shift. An early form of Turkification occurred in the time of the Seljuk Empire among the local population of Anatolia, involving intermarriages, religious conversion, linguistic shift and interethnic relationships, which today is reflected in the genetic makeup of the modern Turkish people. Diverse peoples were affected by Turkification including Anatolian, Balkan, Caucasian, and Middle Eastern peoples with different ethnic origins, such as Albanians, Armenians, Assyrians, Circassians, Georgians, Greeks, Jews, Romani, Slavs, Kurds living in Anatolia, as well as Lazs from all the regions of the Ottoman Empire.

Etymology

:

The term has been used in the Greek language since the 1300s or late-Byzantine era. It literally means "becoming Turk". Apart from persons, it may refer also to cities that were conquered by Turks or churches that were converted to mosques. It is more frequently used in the form of the verb (turkify, become Muslim or Turk).

History

:

Native Iranian population of Central Asia and the steppes part of the region, had also been turkified by the migrating Turkic tribes of Inner Asia by the 6th century A.D. The process of Turkification of Central Asia, besides those parts that today constitute the territory of the present-day Tajikistan, accelerated with the Mongol conquest of Central Asia.

Arrival of Turks to Anatolia :

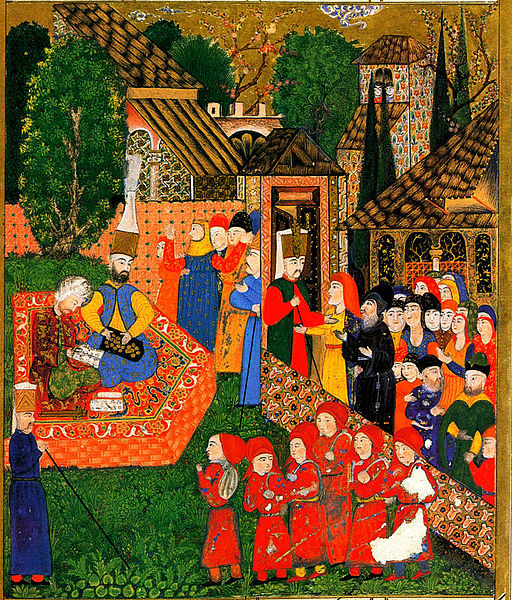

Illustration of the registration of Christian boys for the devsirme. Ottoman miniature painting, 1558 Anatolia was home to many different peoples in ancient times who were either natives or settlers and invaders. These different people included the Armenians, Anatolian peoples, Persians, Hurrians, Greeks, Cimmerians, Galatians, Colchians, Iberians, Arameans, Assyrians, Corduenes, and scores of others. The presence of many Greeks, the process of Hellenization, and the similarity of some of the native languages of Anatolia to Greek (cf. Phrygian), gradually caused many of these peoples to abandon their own languages in favor of the eastern Mediterranean lingua franca, Koine Greek, a process reinforced by Romanization. By the 5th century the native people of Asia Minor were entirely Greek in their language and Christian in religion. These Greek Christian inhabitants of Asia Minor are known as Byzantine Greeks, and they formed the bulk of the Byzantine Empire's Greek-speaking population for one thousand years, from the 5th century until the fall of the Byzantine state in the 15th century. In the northeast along the Black Sea these peoples eventually formed their own state known as the Empire of Trebizond, which gave rise to the modern Pontic Greek population.

In the east, near the borderlands with the Persian Empire, other native languages remained, specifically Armenian, Assyrian Aramaic, and Kurdish. Byzantine authorities routinely conducted large-scale population transfers in an effort to impose religious uniformity and quell rebellions. After the subordination of the First Bulgarian Empire in 1018, for instance, much of its army was resettled in Eastern Anatolia. The Byzantines were particularly keen to assimilate the large Armenian population. To that end, in the eleventh century, the Armenian nobility were removed from their lands and resettled throughout western Anatolia with prominent families subsumed into the Byzantine nobility, leading to numerous Byzantine generals and emperors of Armenian extraction. These resettlements spread the Armenian-speaking community deep into Asia Minor, but an unintended consequence was the loss of local military leadership along the eastern Byzantine frontier, opening the path for the inroads of Turkish invaders. Beginning in the eleventh century, war between the Turks and Byzantines led to the deaths of many in Asia Minor, while others were enslaved and removed. As areas became depopulated, Turkic nomads moved in with their herds.

Number

of pastoralists of Turkic origin in Anatolia :

According to Ottoman tax archives, in modern-day Anatolia, in Anatolia Eyalet, Karaman Eyalet, Dulkadir Eyalet and Rûm Eyalet provinces there were about 872,610 households in the 1520s and 1530s; 160,564 of those households were nomadic, and the remainder were sedentary. Of four provinces, province of Anatolia had the largest nomadic population with 77,268 households. (note: province of Anatolia does not include entire Anatolia, it includes Western Anatolia and some parts of Northwestern Anatolia only) Between 1570 and 1580, 220,217 households of the total 1,360,474 households in the four provinces were nomadic which means, at least 20% of Anatolia was still nomadic in the 16th century. The province of Anatolia, which had the largest nomadic population with 77,268, saw an increase in its nomadic population. 116,219 households in those years in province of Anatolia were nomadic.

Devsirme

:

Late

Ottoman era :

One of its main supporters was sociologist and political activist Ziya Gökalp who believed that a modern state must become homogeneous in terms of culture, religion, and national identity. This conception of national identity was augmented by his belief in the primacy of Turkishness, as a unifying virtue. As part of this belief, it was necessary to purge from the territories of the state those national groups who could threaten the integrity of a modern Turkish nation state. The 18th article of the Ottoman Constitution of 1876 declared Turkish the sole official language, and that only Turkish speaking people could be employed in the government.

After the Young Turks assumed power in 1909, the policy of Turkification received several new layers and it was sought to impose Turkish in the administration, the courts and education in the areas where the Arabic speaking population was the majority. Another aim was to loosen ties between the Empire's Turk and ethnically non-Turkish populations through efforts to purify the Turkish language of Arabic influences. In this nationalist vision of Turkish identity, language was supreme and religion relegated to a subordinate role. Arabs responded by asserting the superiority of Arabic language, describing Turkish as a "mongrel" language that had borrowed heavily from the Persian and Arabic languages. Through the policy of Turkification, the Young Turk government suppressed Arabic language. Turkish teachers were hired to replace Arabic teachers at schools. The Ottoman postal service was administrated in Turkish.

Those who supported Turkification were accused of harming Islam. Rashid Rida was an advocate who supported Arabic against Turkish. Even before the Young Turk Revolution of 1908, the Syrian Reformer Tahrir al-Jazairi had convinced Midhat Pasha to adopt Arabic as the official language of instruction at state schools. The language of instruction was only changed to Turkish in 1885 under Sultan Abdulhamid. Though writers like Ernest Dawn have noted that the foundations of Second Constitutional Era "Arabism" predate 1908, the prevailing view still holds that Arab nationalism emerged as a response to the Ottoman Empire's Turkification policies. One historian of Arab nationalism wrote that: "the Unionists introduced a grave provocation by opposing the Arab language and adopting a policy of Turkification", but not all scholars agree about the contribution of Turkification policies to Arab nationalism.

European critics who accused the CUP of depriving non-Turks of their rights through Turkification saw Turk, Ottoman and Muslim as synonymous, and believed Young Turk "Ottomanism" posed a threat to Ottoman Christians. The British ambassador Gerard Lowther said it was like "pounding non-Turkish elements in a Turkish mortar", while another contemporary European source complained that the CUP plan would reduce "the various races and regions of the empire to one dead level of Turkish uniformity." Rifa'at 'Ali Abou-El-Haj has written that "some Ottoman cultural elements and Islamic elements were abandoned in favor of Turkism, a more potent device based on ethnic identity and dependent on a language based nationalism".

The Young Turk government launched a series of initiatives that included forced assimilation. Ugur Üngör writes that "Muslim Kurds and Sephardi Jews were considered slightly more 'Turkifiable' than others", noting that many of these nationalist era "social engineering" policies perpetuated persecution "with little regard for proclaimed and real loyalties." These policies culminated in Armenian and Assyrian genocides.

During World War I, the Ottoman government established orphanages throughout the empire which included Armenian, Kurdish and Turkish children. Armenian orphans were given Arabic and Turkish names. In 1916 a Turkification campaign began in which whole Kurdish tribes were to be resettled in areas where they were not to exceed more than 10% of the local population. Talaat Pasha ordered that Kurds in the eastern areas be relocated in western areas. He also demanded information regarding if the Kurds turkefy in their new settlements and if they get along with their Turkish population. Also non-Kurdish immigrants from Greece, Albania, Bosnia and Bulgaria were to be settled in the Diyarbakir province, where the deported Kurds have lived before. By October 1918, with the Ottoman army retreating from Lebanon, a Father Sarlout sent the Turkish and Kurdish orphans to Damascus, while keeping the Armenian orphans in Antoura. He began the process of reversing the Turkification process by having the Armenian orphans recall their original names. It is believed by various scholars, that at least two million Turks have at least one Armenian grandparent.

Around 1.5 million Ottoman Greeks remained in the Ottoman Empire after losses of 550,000 during WWI. Almost all, 1,250,000, except for those in Constantinople, had fled before or were forced to go to Greece in 1923 in the population exchanges mandated by the League of Nations after the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922). The lingual Turkification of Greek-speakers in 19th-century Anatolia is well documented. According to Speros Vryonis the Karamanlides are the result of partial Turkification that occurred earlier, during the Ottoman period. Fewer than 300,000 Armenians remained of 1.8 million before the war; fewer than 100,000 of 400,000 Assyrians.

Modern

Turkey :

The process of unification through Turkification continued within modern Turkey with such policies as :

•

According to

Art. 12 of the Turkish Constitution of 1924, citizens who could

not speak and read Turkish were not allowed to become members of

parliament.

During Ottoman times, the millet system defined communities on a religious basis, and a residue remains today in that Turkish villagers will commonly consider as Turks only those who profess the Sunni faith, and they consider Turkish-speaking Jews, Christians, or even Alevis to be non-Turks.

The imprecision of the appellation Türk can also be seen with other ethnic names, such as Kürt, which is often applied by western Anatolians to anyone east of Adana, even those who speak only Turkish. On the other hand, Kurdish-speaking or Arabic-speaking Sunnis of eastern Anatolia are often considered to be Turks.[verification needed]

Thus, the category Türk, like other ethnic categories popularly used in Turkey, does not have a uniform usage. In recent years, centrist Turkish politicians have attempted to redefine this category in a more multicultural way, emphasizing that a Türk is anyone who is a citizen of the Republic of Turkey. Now, article 66 of the Turkish Constitution defines a "Turk" as anyone who is "bound to the Turkish state through the bond of citizenship".

Genetic

testing of language replacement hypothesis in Anatolia, Caucasus

and Balkans :

In 2014, however, the largest autosomal study on Turkish genetics (on 16 individuals) concluded the weight of East Asian (presumably Central Asian) migration legacy of the Turkish people is estimated at 21.7%. The authors conclude on the basis of previous studies that "South Asian contribution to Turkey's population was significantly higher than East/Central Asian contributions, suggesting that the genetic variation of medieval Central Asian populations may be more closely related to South Asian populations, or that there was continued low level migration from South Asia into Anatolia." They note that these weights are not direct estimates of the migration rates as the original donor populations are not known, and the exact kinship between current East Asians and the medieval Oghuz Turks is uncertain. For instance, genetic pools of Central Asian Turkic peoples is particularly diverse and modern Oghuz Turkmens living in Central Asia are with higher West Eurasian genetic component than East Eurasian on average.

These findings are consistent with a model in which the Turkic languages, originating in the Altai-Sayan region of Central Asia and northwestern Mongolia, were imposed on the indigenous peoples with genetic admixture, shows both ethnic mixing and linguistic replacement. Genetically, Anatolian Turks were more closely related also with Balkan populations than to the Central Asian populations in early history. After eleven decades of Turkic migration to Anatolia including Oghuz and Kipchak Turkic people from Central Asia, Persia, Caucassia and Crimea, today's population is genetically in between Central Asia and indigenous historic Anatolia. Similar results come from neighbouring Caucasus region by testing Armenian and Turkic speaking Azerbaijani populations, therefore representing language replacements and intermarriages. As of 2004, the haplogroups in Turkey are shared with European and neighboring Near Eastern populations and haplogroups related to Central Asian, South Asian and African affinity, which supports both the mass migration, and language replacement hypothesis on the region and ethnic mixing.

A 2011 haplogroup study concluded "that the profile of Anatolian populations today is the product not of mass westward migrations of Central Asians and Siberians, or of small-scale migrations into an emptied subcontinent, but instead of small-scale, irregular punctuated migration events that engendered large-scale shifts in language and culture among the diverse" indigenous inhabitants (p. 32). Results of a 2012 genetic study by Hodoglugil and Mahley showed the admixture of Turkish people, which is primarily European (French, Italian, Sardinian) and Middle Eastern (Druze, Palestinian), with a Central Asian (Uyghur, Kyrgyz, Hazara) component of only 9%-15% of their genepool.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |