| PARSA / PERSIA

Glazed tile work from Palace of Darius I, the Great, at Susa, now at the Iranian National Museum, Tehran. Photo Credit: youngrobv (Rob & Ale) at Flickr Nomenclature

:

English: Persia, Modern Persian: Pars, Old Persian: Parsa, Greek: Persica & Persis, Assyrian / Akkadian: Parsua.

Persian Entry Into Aryan / Iranian Group of Nations

In the second phase of Zoroastrian history - a post-Avestan phase that started in the first millennium BCE - Airyana Vaeja would become the distant memory of a land preserved in legend and scripture. While the Shahnameh and Pahlavi works continued to record the history of this phase, we also have the written histories of classical Greek writers and Assyrian / Babylonian inscriptions. The centre of Zoroastrianism in the second phase would shift westward and would be centred around the nation of Persia, a nation by whose name the world would call the Aryan lands of Iran, Iran being a name derived from Airan Vej - the previous Airyana Vaeja (also see Iran and Persia - the Same?).

Persians and Medes as Aryans :

Greek historian Herodotus (c. 485-420 BCE ) in his Histories notes 7.62: "The Medes had exactly the same equipment as the Persians; and indeed the dress common to both is not so much Persian as Median. They had for commander Tigranes, of the lineage of the Achaemenids. These (the Medes & Persians) were called anciently by all people Aryans." Herodotus says that the Median (and Persian) association as Aryans was already 'ancient' in relation to the mid-first millennium BCE, the time when he lived. He also confirms the Aryan heritage of all Medes and Persians.

Strabo (c. 63/64-24 ACE) also notes in his Geography 15.2.8 "the name of Aryana (Ariana) is further extended to a part of Persia and of Media, as also to the Bactrians and Sogdians on the north; for these speak approximately the same language, with but slight variations."

These statements inform us that Persia and Media were among the various Aryan states and a part of the greater Aryan nation. Initially, the Medes and then the Persian, sought to unify all the Aryan states, Aryana, as one empire.

[As an aside we note that the Zoroastrian and Hindu scriptures, the Avesta and the Rig Ved respectively are the only contemporaneous ancients texts that make references to Aryans. The next references are in the inscriptions of the Achaemenian Persians and in the classical Greek texts noted above.]

Persians as Migrants :

In addition, while the Achaemenian kings called themselves kings of Parsa in local inscriptions, the kings up to Cyrus the Great called themselves kings of Anshan in inscriptions outside of Persia and Media. The clay cylinder of Cyrus the Great found in Babylon states that Cyrus is "king of Anshan". Parsa is not mentioned in this text. The title 'King of Susa and Anshan' or 'King of Susa and Anshan' had previously been used by Elamite kings from c. 1500 BCE (cf. The Archaeology of Elam by Daniel T. Potts, 1999). The last Elamite king to claim this title was Shutruk-Nahhunte II (c. 717-699 BCE). Between 675 and 640 BCE, this title was claimed by the Achaemenian king Teispes / Cishpaish.

We find no hint in the record, or in tradition, or in scripture, of the Persian Aryans, the Parsa, being native to the Elamite lands of Anshan. To locate the Parsa before their establishment in Anshan, we have to look elsewhere.

In the centuries before the Persian Achaemenian kings began to call themselves kings of Anshan, Assyrian inscriptions mention lands or peoples called Parsumash (or Parsamash), Parsuash and Parsua - lands north of Anshan along the central slopes of the Zagros mountains.

These observations have led to the commonly held proposition that the Persians migrated to Anshan - the land that would come to be known as Parsa - from an earlier land based further north along the Zagros mountains, and before that from the homeland of the Aryans. If the Persians were indeed immigrants to Parsa, then Assyrian inscriptions might give us clues about predecessor nations formed by the ancestors of the Persians: the nations of Parsumash, Parsuash and Parsua - Parsua being the nation about which we see the earliest mention.

In addition, medieval literature claims that Zoroastrianism arose in Azerbaijan or the region around Lake Urmia - just north of and in proximity to the north-central Zagros valleys of Parsua. We continue these discussions below.

[For indications of a yet prior homeland of the ancient Persians, a homeland in the original eastern Aryan lands, see the section on Parsiban in our page on Aria.]

References

:

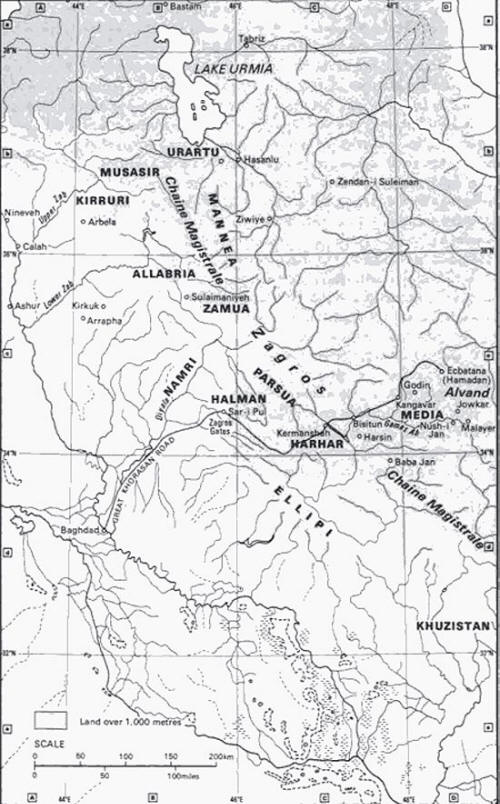

Map of Ancient Persian & Mesopotamian States. Base map courtesy Microsoft Encarta Lake

Urmia & the Early Parsua (9th Century BCE) :

In other medieval references, Shiz is said to be a centre of ancient Zoroastrianism. Shiz is frequently identified with the Avestan Chaechista / Chichast, a name that is associated by Professor Jackson and others with Lake Urmiah. Today, Shiz is identified with ruins at Takab, located in the southeast corner of West Azerbaijan province and close to the suggested location of Madai (Ak.) / Mada (OP) (Media) and Parsua.

If the early Persians did at some point in history reside in Parsua, then they first enter written history in a 844 BCE Assyrian inscription that recorded a successful military expedition by King Shalmaneser III (859-824 BCE) in the north-central Zagros ranges south of Lake Urmia. Shalmaneser's inscription records that he exacted tribute from twenty-seven 'kings' or chieftains of Parsua. We also gather from the inscriptions that the people of Parsua were organized as loose federations of autonomous districts, each with its own chief. Different authors locate Parsua to the west or to the south of Lake Urmia. We discuss the possible location below in the section on the Extent of Early Parsua.

[A note on page 61 in The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. 2, says " that the term Parsua is always used... with the determinative of 'country', never with that of tribe: 'the tribe of Parsua' is a historical myth." At times, we also find the word Parsuash used in the inscriptions, along with the determinative 'people'.]

Map of Ancient Lands in the Urmia-Zagros Region. Image credit: The Cambridge Ancient History

Extent of Parsua (8th Century BCE) :

In today's terms, the land of 8th Century BCE Parsua would include southern Kurdistan and northern Kermanshah in Iran. A natural location for the early Persians to settle would have been around the trade road that was later called the Great Khorasan Road.

Since the early Persian groups may not have been unified at this time, Parsua could have existed in pockets spread over several valleys. We do know that Shalmaneser's inscription states that he exacted tribute from 27 Parsua chieftains or kings and we may be safe to conclude there were at least 27 different Parsua districts (later when they did unite, Herodotus mentions ten different Persian groups or 'tribes').

Constant Assyrian Raids, Destruction & Looting :

Sir Percy Sykes in his book A History of Persia (1915) extracts references to Medians and Persians in various Assyrian inscriptions. The inscriptions catalogue centuries of violent raids and looting of the Persian and Mede settlements by the Assyrians.

For instance, one Assyrian inscription states that Shalmaneser's successor, King Shamsi-Adad (823-810 BCE) destroyed 1,200 towns or settlements in Parsua in the region of present day Kermanshah. He also conducted raids further east into Median lands. His armies crossed the Kullar mountains (the main Zagros range) and entered Messi on the upper reaches of the River Jagatu, where they captured a large quantity of cattle, sheep and a number of two-humped Bactrian camels. The capture of Bactrian camels is very significant as they were widely used by Aryan traders.

The Assyrian raids continued, and in 810 BCE, Shamsi-Adad's successor Adad-Nirari led the first of four expeditions against the Medes and Persians.

Then in 744 BCE King Pul or Tiglath-Piliser IV, invaded Media and returned to his capital Ashur with 60,500 prisoners and enormous herds of cattle, oxen, sheep, mules and camels.

In 716 BCE, King Sargon II (reign c. 722-705 BCE) of Assyria allied with Urartians invaded the lands south of Lake Urmia, occupied Mannea, and stationed troops in Parsuash and Media. Sargon's raid on Parsuash and Media in 710 BCE resulted in his demise - a death Sargon's son and successor, Sennacherib chose to interpret as divine punishment. (Also see Project Gutenberg's Babylonian and Assyrian Literature.)

Sykes concludes "... it would appear, from the frequency with which expeditions raided the Iranian plateau and from the number of towns destroyed, that it (the Median and Persian lands) was then a distinctly fertile and well populated country. The inference is confirmed by the number of prisoners and the thousands of horses, cattle and sheep that were captured."

Impetus to Migrate :

Preserving trade could have been an added incentive. It has been suggested by other authors (cf. T. Cutler Young in The Cambridge Ancient History IV) that the Assyrian focus on the Central Zagros was in part to plunder and even cut off the trade routes that were enriching their competitors - Babylonia and Elam. If so, new and safer trade routes to Susa via the lower Zagros could have prompted the Aryan trading communities to move south to the trade centres on the new trade route.

Migration & Trade :

In addition, the early Persians could have migrated over different periods of time using several routes. A modern example is the migration of Zoroastrians to India and then to other parts of the world. The Parsees arrived in India using different routes over a span of time. It is possible that earlier groups helped establish bases where later immigrants congregated. Given Zoroastrian history where there is little evidence of a block migration, and indeed more to the contrary, a fractured migration is a more likely scenario. In this event, there could have more than one Persian enclave or settlement or kingdom existing at several Zagros (and other) locations simultaneously. Eventually, one of these locations would attract others for reasons of security, marriage, opportunity and building community.

Indo-Iranian Aryans were known to have established trading communities all along the Aryan trade roads (otherwise called the Silk Roads) from China to the Upper Indus valley and Central Turkey. These trading communities could have attracted additional members of the communities from which they came, for various reasons, including a displacement because of invasions or wars.

Later in history, and once the Persians had been united, Persian King Darius I (the Great) developed some arms of the trade roads into the Royal Road known mainly for the 2,857 km arm from the city of Susa on the lower Tigris to the port of Smyrna (modern Izmir in Turkey) on the Aegean Sea. We know about this section through the Histories of Herodotus 5.52-5.53. Herodotus notes that "Royal stations exist along its whole length, and excellent caravanserais; and throughout, it traverses an inhabited tract, and is free from danger." These are essential conditions for the conduct of trade.

However, in this point in history, since the Persians were still a loose collection of related groups who had not as yet been united by a strong leader, we can expect that while some groups migrated southward, others may have continued to live in Parsua during the initial migratory phases.

Source :

http://www.heritageinstitute.com/ |