| ALCHON HUNS

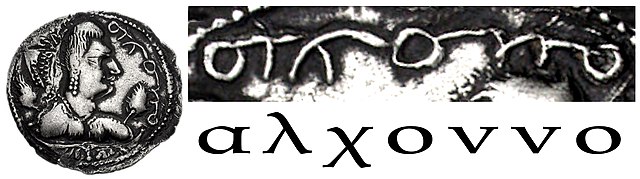

Portrait of Alchon king Khingila (c. 450 CE), and the bull / lunar tamga of the Alchon, as visible on Alchon coinage

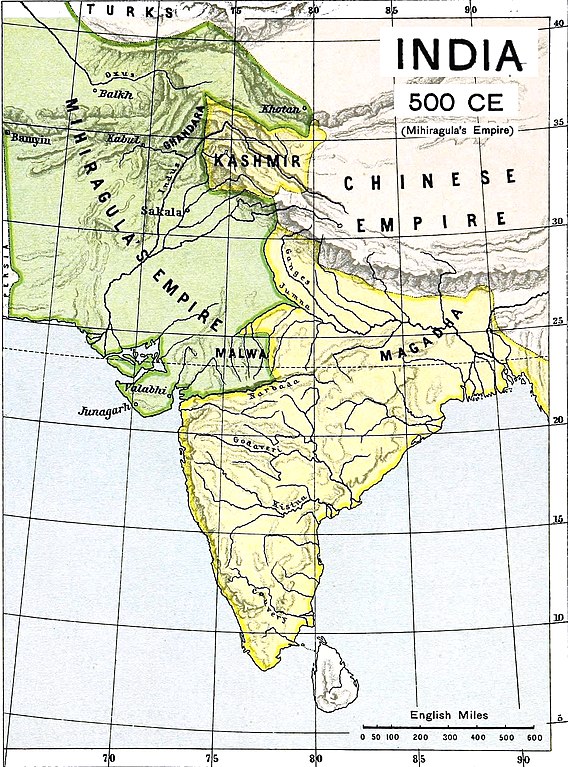

Find spots of epigraphic inscriptions indicating local control by the Alchon Huns in India between 500 - 530 CE Alchon Huns

370 - 670

Capital : Kapisa

Common languages : Brahmi and Bactrian (written)

Religion : Hinduism, Buddhism

Government : Nomadic empire

Historical era : Late Antiquity

• Established : 370

• Disestablished : 670

Currency : Drachm

Preceded by

Sassanian

Empire

Succeeded by

Hephthalites

Nezak

Huns

Aulikaras

Turk

Shahi

The Alchon Huns, also known as the Alchono, Alxon, Alkhon, Alkhan, Alakhana and Walxon, were a nomadic people who established states in Central Asia and South Asia during the 4th and 6th centuries CE.

They were first mentioned as being located in Paropamisus, and later expanded south-east, into the Punjab and central India, as far as Eran and Kausambi.

The Alchon invasion of the Indian subcontinent eradicated the Kidarite Huns who had preceded them by about a century, and contributed to the fall of the Gupta Empire, in a sense bringing an end to Classical India.

The invasion of India by the Hun peoples follows invasions of the subcontinent in the preceding centuries by the Yavan (Indo-Greeks), the Saka (Indo-Scythians), the Palav (Indo-Parthians), and the Kushan (Yuezhi). The Alchon Empire was the third of four major Hun states established in Central and South Asia. The Alchon were preceded by the Kidarites and succeeded by the Hephthalites in Bactria and the Nezak Huns in the Hindu Kush. The names of the Alchon kings are known from their extensive coinage, Buddhist accounts, and a number of commemorative inscriptions throughout the Indian subcontinent.

The Alchons have long been considered as a part or a sub-division of the Hephthalites, or as their eastern branch, but now tend to be considered as a separate entity.

Identity

:

The word "Alchono" in the Greco-Bactrian cursive script, on a coin of Khingila The Huns appear to have been the peoples known in contemporaneous Iranian sources as Xwn, Xiyon and similar names, which were later Romanised as Xionites or Chionites. The Huns are often linked to the Huns that invaded Europe from Central Asia during the same period.

Consequently, the word Hun has three slightly different meanings, depending on the context in which it is used: 1) the Huns of Europe; 2) groups associated with the Hun people who invaded northern India; 3) a vague term for Hun-like people. The Alchon have also been labelled "Huns", with essentially the second meaning, as well as elements of the third.

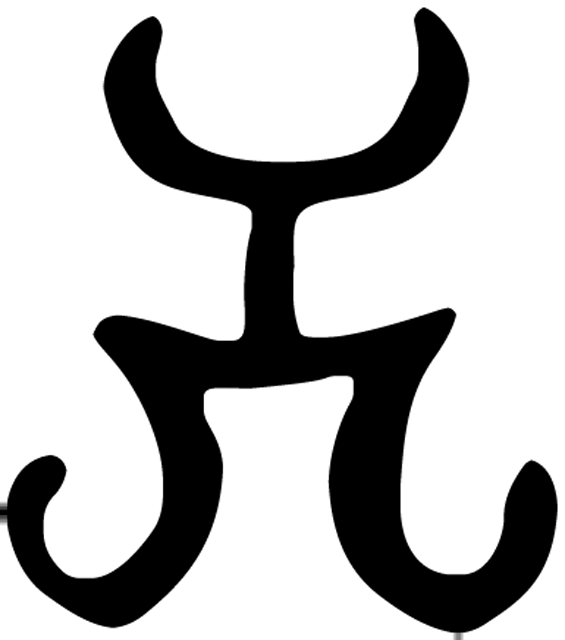

The name "Alchon" generally given to them comes from the Bactrian legend of their early coinage, where they simply imitated Sassanian coins to which they added the name "alchono" in Bactrian script (a slight adaptation of the Greek script) and the tamgha symbol of their clan. Several original coins such as those of Khingila also bear the mention "alchono" together with the Tamgha symbol.

Philologically, "alchono" may be a combination of al- for Aryan and -xono for Huns, although this remains hypothetical. Another etymology could be al-, Turkish for scarlet, and -xono for Huns, meaning "Red Huns", red being a symbol of the south among steppe nomads.

Visual appearance :

Portrait of Alchon king Khingila, fom his coinage (circa 450 CE)

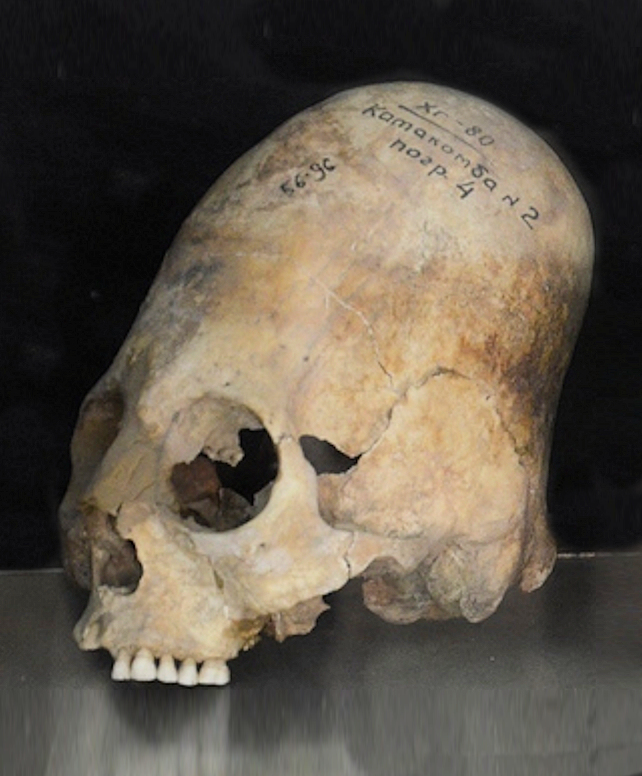

Elongated skull excavated in Samarkand (dated 600 - 800 CE), Afrasiab Museum of Samarkand The Alchons are generally recognized by their elongated skull, a result of artificial skull deformation, which may have represented their "corporate identity". The elongated skulls appears clearly in most of the portaits of rulers in the coinage of the Alkhon Huns, and most visibly on the coinage of Khingila. These elongated skulls, which they obviously displayed with pride, distinguished them from other peoples, such as their predecessors the Kidarites. On their coins, the spectacular skulls came to replace the Sasanian-type crowns which had been current in the coinage of the region. This practice is also known among other peoples of the steppes, particularly the Huns, and as far as Europe, where it was introduced by the Huns themselves.

In another ethnic custom, the Alchons were represented beardless, often wearing a moustache, in clear contrast with the Sasanian Empire prototype which was generally bearded.

The emblematic look of the Alchons seems to have become rather fashionable in the area, as shown by the depiction of the Iranian hero Rostam, mythical king of Zabulistan, with an elongated skull in his 7th century CE mural at Panjikent.

Symbolism

:

History

:

The Alkhons are initially recorded in the area of Bactria circa 370 CE, from where they confronted the Sasanian Empire to the west and the Kidarites to the southeast.

Appearance of the Alchon tamgha

An early Alchon coin based on the design of Sasanian coinage, with

bust imitating Sasanian king Shapur II (r.309 to 379 CE), only adding

the Alchon Tamgha symbol and "Alchono" in Bactrian script

on the obverse. Dated 400-440 CE.

Early confrontations between the Sasanian Empire of Shapur II with the nomadic hordes from Central Asia called the "Chionites" were described by Ammianus Marcellinus: he reports that in 356 CE, Shapur II was taking his winter quarters on his eastern borders, "repelling the hostilities of the bordering tribes" of the Chionites and the Euseni ("Euseni" is usually amended to "Cuseni", meaning the Kushans), finally making a treaty of alliance with the Chionites and the Gelani, "the most warlike and indefatigable of all tribes", in 358 CE. After concluding this alliance, the Chionites (probably of the Kidarites tribe) under their King Grumbates accompanied Shapur II in the war against the Romans, especially at the Siege of Amida in 359 CE. Victories of the Xionites during their campaigns in the Eastern Caspian lands were also witnesses and described by Ammianus Marcellinus.

The Alchon Huns occupied Bactria circa 370 CE, where they started minting coins in the style of Shapur II but bearing their name "Alchono", and emerged in Kapis around 380, taking over Kabulistan from the Sassanian Persians, at the same time the Kidarites (Red Huns) still ruled in Ghandar. The Alchon Huns are said to have taken control of Kabul in 388.

The Alchon Huns initially issued anonymous coins based on Sasanian designs. Several types of these coins are known, usually minted in Bactria, using Sasanian coinage designs with busts imitating Sasanian kings Shapur II (r.309 to 379 CE) and Shapur III (r.383 to 388 CE), adding the Alchon Tamgha Alchon and the name "Alchono" in Bactrian script (a slight adaptation of the Greek script which had been introduced in the region by the Greco-Bactrians in the 3rd century BCE) on the obverse, and with attendants to a fire altar, a standard Sasanian design, on the reverse. It is thought the Alchons took over the Sasanian mints in Kabulistan after 385 CE, reusing dies of Shapur II and Shapur III, to which they added the name "Alchono".

Gandhar (460 CE) :

Portrait of an older King Khingil, founder of the Alchon Huns, on one of his coins, c. 430 – 490 CE Around 430 King Khingil, the most notable Alchon ruler, and the first one to be named and represented on his coins with the legend (Kiggilo) in Bactrian, emerged and took control of the routes across the Hindu Kush from the Kidarites. He seems to have been a contemporary of the Sassanian ruler Bahram V. As the Alchons took control, diplomatic missions were established in 457 with China. Khingil, under the name Shengil, was called "King of India" in the Shahnameh of Ferdowsi.

Alchon ruler Meham (r.461-493) was elevated to the position of Governor for Sasanian Emperor Peroz I (r. 459-484), and described himself as "King of the people of Kadag and governor of the famous and prosperous King of Kings Peroz" in a 462-463 letter. He allied with Peroz I in his victory over the Kidarites in 466 CE, and may also have helped him take the throne against his brother Hormizd III. But he was later able to wrestle autonomy or even independence.

Between 460 and 470 CE, the Alchons took over Gandhar and the Punjab which also had remained under the control of the Kidarites, while the Gupta Empire remained further east.

The Alkhon Huns may simply have filled the power vaccuum created by the decline of the Kidarites, following their defeat in India against the Gupta Empire of Skandgupt in 455 CE, and their subsequent defeat in 467 CE against the Sasanian Empire of Peroz I, with Hephthalite and Alchon aid under Meham, which put an end to Kidarite rule in Transoxiana once and for all.

The silver bowl in the British Museum

Alchon horseman, possibly Khingil

The so-called "Hephthalite bowl" from Gandhar, features

two Kidarite hunters wearing characteristic crowns, and as well

as two Alchon hunters (one of them shown here, with skull deformation),

suggesting a period of peaceful coexistence between the two entities.

Swat District, Pakistan, 460–479 CE. British Museum.

The Alchons apparently undertook the mass destruction of Buddhist monasteries and stups at Taxila, a high center of learning, which never recovered from the destruction. Virtually all of the Alchon coins found in the area of Taxila were found in the ruins of burned down monasteries, where apparently some of the invaders died alongside local defenders during the wave of destructions.

It is thought that the Kanishk stup, one of the most famous and tallest buildings in antiquity, was destroyed by them during their invasion of the area in the 460s CE.

The rest of the 5th century marks a period of territorial expansion and eponymous kings, several of which appear to have overlapped and ruled jointly. The Alchon Huns invaded parts of northwestern India from the second half of the 5th century. According to the Bhitari pillar inscription, the Gupta ruler Skandgupt already confronted and defeated an unnamed Hun ruler circa 456-457 CE.

Sindh :

Uncertain Hunnic chieftain. Sindh. 5th century From circa 480 CE, there are also suggestion of Hunnic occupation of Sindh, between Multan and the mouth of the Indus river, as the local Sasanian coinage of Sindh starts to incorporate sun symbols or a Hunnic tamgha to the design.

These little-known coins are usually described as the result of the invasions of the "Hephthalites". The quality of the coins also becomes very much degraded by that time, and the actual gold content becomes quite low compared to the previous Sasanian-style coinage.

Contributions :

The Huns were precisely ruling the area of Malwa, at the doorstep of the Western Deccan, at the time the famous Ajanta caves were made by ruler Harisen of the Vaktak Empire. Through their control of vast areas of northwestern India, the Huns may actually have acted as a cultural bridge between the area of Gandhar and the Western Deccan, at the time when the Ajanta or Pitalkhora caves were being decorated with designs of Gandharan inspiration, such as Buddhas dressed in robes with abundant folds.

First Hunnic War: Central India :

Kausambi

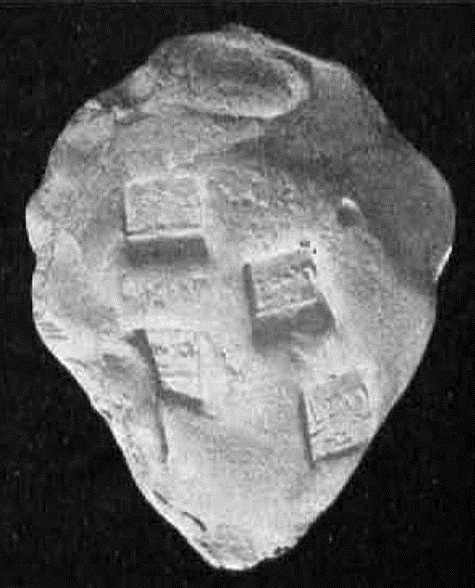

The monastery of Ghoshitarama in Kausambi was probably destroyed by the Alchon Huns under Toramana

"Hun Raja" Toramana seal impression, Kausambi In the First Hunnic War (496–515), the Alchon reached their maximum territorial extent, with King Toramana pushing deep into Indian territory, reaching Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh in Central India, and ultimately contributing to the downfall of the Gupta Empire.

To the south, the Sanjeli inscriptions indicate that Toramana penetrated at least as far as northern Gujarat, and possibly to the port of Bharukacch. To the east, far into Central India, the city of Kausambi, where seals with Toramana's name were found, was probably sacked by the Alkhons in 497–500, before they moved to occupy Malwa.

In particular, it is thought that the monastery of Ghoshitaram in Kausambi was destroyed by Toraman, as several of his seals were found there, one of them bearing the name Toraman impressed over the official seal of the monastery, and the other bearing the title Hunraj ("King of the Huns"), together with debris and arrowheads. Another seal, this time by Mihirkul, is reported from Kausambi. These territories may have been taken from Gupta Emperor Budhgupt. Alternatively, they may have been captured during the rule of his successor Narsimhagupt.

First

Battle of Eran (510 CE) :

Portrait of Toraman and Gupta script initials Gupta allahabad to Tora, from his bronze coinage. He sacked Kausambi and occupied Malwa According to a 6th-century CE Buddhist work, the Manjusri-mula-kalp, Bhanugupt lost Malwa to the "Shudra" Toraman, who continued his conquest to Magadh, forcing Narasimhagupt Baladitya to make a retreat to Bengal. Toraman"possessed of great prowess and armies" then conquered the city of Tirth in the Gaud country (modern Bengal). Toraman is said to have crowned a new king in Banaras, named Prakataditya, who is also presented as a son of Narsimha Gupta.

The Eran "Varaha" boar, under the neck of which can be found the Eran boar inscription mentioning the rule of Toraman

Maharajdhiraj Shri Toraman "Great King of Kings, Lord Toraman" in the Eran boar inscription of Toraman in the Gupta script

A rare gold coin of Toraman in the style of the Guptas. The obverse legend reads: "The lord of the Earth, Toraman, having conquered the Earth, wins Heaven" Having conquered the territory of Malwa from the Guptas, Toraman was mentioned in a famous inscription in Eran, confirming his rule on the region. The Eran boar inscription of Toraman (in Eran, Malwa, 540 km south of New Delhi, state of Madhya Pradesh) of his first regnal year indicates that eastern Malwa was included in his dominion. The inscription is written under the neck of the boar, in 8 lines of Sanskrit in the Brahmi script. The first line of the inscription, in which Toraman is introduced as Maharajadhiraj (The Great King of Kings), reads :

"In year one of the reign of the King of Kings Sri-Toraman, who rules the world with splendor and radiance..."

—

Eran boar inscription of Toraman.

"Avanipati Torama(no) vijitya vasudham divam jayati"

"The lord of the Earth, Toraman, having conquered the Earth, wins Heaven"

—

Toraman gold coin legend.

Defeat

(515 CE) :

Toraman was finally vanquished with certainty by an Indian ruler of the Aulikar dynasty of Malwa, after nearly 20 years in India. According to the Risthal stone-slab inscription, discovered in 1983, King Prakashadharma defeated Toraman in 515 CE.

The First Hunnic War thus ended with a Hunnic defeat, and Hunnic troops apparently retreated to the area of Punjab.

The Manjusri-mul-kalp simply states that Toraman died in Banaras as he was returning westward from his battles with Narasimhagupt.

Second Hunnic War: to Malwa and retreat :

Mihirkul on one of his coins. He was finally defeated in 528 by King Yasodharman The Second Hunnic War started in 520, when the Alchon king Mihirkul, son of Toraman, is recorded in his military encampment on the borders of the Jhelum by Chinese monk Song Yun. At the head of the Alchon, Mihirkul is then recorded in Gwalior, Central India as "Lord of the Earth" in the Gwalior inscription of Mihirkul. According to some accounts, Mihirkul invaded India as far as the Gupta capital Pataliputra, which was sacked and left in ruins.

There was a king called Mo-hi-lo-kiu-lo (Mihirkul), who established his authority in this town (Sagal) and ruled over India. He was of quick talent, and naturally brave. He subdued all the neighbouring provinces without exception.

—

Xuanzang "The Record of the Western Regions", 7th century

CE

“Mihirkul, a man of violent acts and resembling Kaal (Death) ruled in the land which was overrun by hordes of Malechs… the people knew his approach by noticing the vultures, crows, and other [birds], which were flying ahead to feed on those who were being slain within his army’s [reach]”

— The Rajatarangini

Pillar of Yashodharman near Mandsaur, with the Sondani inscription claiming victory over Mihirkul of the Alchons in 528 CE Finally however, Mihirkul was defeated in 528 by an alliance of Indian principalities led by Yasodharman, the Aulikar king of Malwa, in the battle of Sondani in Central India, which resulted in the loss of Alchon possessions in the Punjab and north India by 542.

The Sondani inscription in Sondani, near Mandsaur, records the submission by force of the Huns, and claims that Yasodharman had rescued the earth from rude and cruel kings, and that he "had bent the head of Mihirkul". In a part of the Sondani inscription Yasodharman thus praises himself for having defeated king Mihirkul :

Mihirkul used the Indian Gupta script on his coinage. Obv: Bust of king, with legend in Gupta script (Ja)yatu Mihirkul ("Let there be victory to Mihirkul"). Rev: Dotted border around Fire altar flanked by attendants, a design adopted from Sasanian coinage.

He (Yasodharman) to whose two feet respect was paid, with complimentary presents of the flowers from the lock of hair on the top of (his) head, by even that (famous) king Mihirkul, whose forehead was pained through being bent low down by the strength of (his) arm in (the act of compelling) obeisance

—

Sondani pillar inscription

Retreat to Gandhar and Kashmir (530 CE) :

Coinage

of Sri Pravarsen, successor of Mihirkul, and supposed founder of

Srinagar. Obverse: Standing king with two figured seated below.

Name "Pravarsen". Reverse: goddess seated on a lion. Legend

"Kidar". Circa 6th-early 7th century CE.

Portrait of Narendraditya Khinkhila, from his coinage Pravarsen was probably succeeded by a king named Gokarn, a follower of Shiv, and then by his son king Narendraditya Khinkhil. The son of Narendraditya was Yudhishthir, who succeeded him as king, and was the last known king of the Alchon Huns. According to the Rajatarangini, Yudhishthir ruled 40 years until circa 670 CE, but he was dethroned by Pratapaditya, son of the founder of the Karkot Empire, Durlabhavardhan.

Retreat to Kabulistan :

Alchon-Nezak "crossover coinage", 580 – 680. Nezak-style bust on the obverse, and Alchon tamga within double border on the reverse Around the end of the 6th century CE, the Alchons withdrew to Kashmir and, pulling back from Punjab and Gandhar, moved west across the Khyber pass where they resettled in Kabulistan. There, their coinage suggests that they merged with the Nezak – as coins in Nezak style now bear the Alchon tamga mark.

During the 7th century, continued military encounters are reported between the Huns and the northern Indian states which followed the disappearance of the Gupta Empire. For example, Prabhakarvardhan, the Vardhan dynasty king of Thanesar in northern India and father of Harsh, is reported to have been "A lion to the Hun deer, a burning fever to the king of the Indus land".

The Alchons in India declined rapidly around the same time that the Hephthalites, a related group to the north, were defeated by an alliance between the Sassanians and the Western Turkic Kaghanate in 557–565 CE.The areas of Khuttal and Kapis-Gandhar had remained independent kingdoms under the Alchon Huns, under kings such as Narendra, but in 625 CE they were taken over by the expanding Western Turks when they established the Yabghus of Tokharistan. Eventually, the Nezak-Alchons were replaced by the Turk Shahi dynasty around 665 CE.

Religion and ethics :

Meditating Buddha from Sarnath, Gupta era, 5th century CE The four Alchon kings Khingil, Toraman, Javukh, and Meham are mentioned as donors to a Buddhist stup in the Talagan copper scroll inscription dated to 492 or 493 CE, that is, at a time before the Hunnic wars in India started. This corresponds to a time when the Alchons had recently taken control of Taxila (around 460 CE), at the center of the Buddhist regions of northwestern India.

Persecution

of Buddhism :

In particular, the writings of Chinese monk Xuanzang from 630 CE explained that Mihirkul ordered the destruction of Buddhism and the expulsion of monks. Indeed, the Buddhist art of Gandhar, in particular Greco-Buddhist art, becomes essentially extinct around that period. When Xuanzang visited northwestern India in c. 630 CE, he reported that Buddhism had drastically declined, and that most of the monasteries were deserted and left in ruins.

Although the Guptas were traditionally a Brahmanical dynasty, around the period of the invasions of the Alchon the Gupta rulers had apparently been favouring Buddhism. According to contemporary writer Paramarth, Mihirkul's supposed nemesis Narsimhagupt Baladitya was brought up under the influence of the Mahayanist philosopher Vasubandhu. He built a sanghram at Nalanda and a 300 ft (91 m) high vihar with a Buddh statue within which, according to Xuanzang, resembled the "great Vihar built under the Bodhi tree". According to the Manjushrimulakalp (c. 800 CE), king Narsimhsagupt became a Buddhist monk, and left the world through meditation (Dhyan). Xuanzang also noted that Narsimhagupt Baladitya's son Vajra, who also commissioned a sangharam, "possessed a heart firm in faith".

The 12th century Kashmiri historian Kalhan also painted a dreary picture of Mihirkul's cruelty, as well as his persecution of the Buddhist faith :

Solar symbolism

Solar symbol on the coinage of Toramana

Khingil with solar symbol

Alchon king with small male figure wearing solar nimbus "In him, the northern region brought forth, as it were, another god of death, bent in rivalry to surpass... Yam (the god of death residing in the southern regions). People knew of his approach by noticing the vultures, crows and other birds flying ahead eager to feed on those who were being slain within his army's reach.

The royal Vetal (demon) was day and night surrounded by thousands of murdered human beings, even in his pleasure houses. This terrible enemy of mankind had no pity for children, no compassion for women, no respect for the aged"

—

12th century Kashmiri historian Kalhan

Mihirkul is said to have been the founder of the Shankaracharya Temple, a shrine dedicated to Shiv in Srinagar, a shrine to Shiv named Mihiresvar in Halad, and a large city called Mihirpur.

Consequences

on India :

Destructions :

Alchon territories of Mihirakula, c. 500 CE (in green) Indian urban culture was left in decline. Major traditional cities, such as Kausambi and probably Ujjain were in ruins, Vidisha and Mathura fell into decline. Buddhism, gravely weakened by the destruction of monasteries and the killing of monks, started to collapse. Great centers of learning were destroyed, such as the city of Taxila, bringing cultural regression. The art of Mathura suffered greatly from the destructions brought by the Huns, as did the art of Gandhar in the northwest, and both schools of art were nearly wiped out under the rule of the Hun Mihirkul. New cities arose from these destructions, such as Dashpur, Kanyakubj, Sthaneshvar, Valabhi and Shripur.

Political

fragmentation :

Rise

of Saivism :

International

trade :

During their rule of 60 years, the Alchons are said to have altered the hierarchy of ruling families and the Indian caste system. For example, the Huns are often said to have become the precursors of the Rajputs. On the artistic side however, the Alchon Huns may have played a role, just like the Western Satraps centuries before them, in helping spread the art of Gandhar to the western Deccan region.

Coinage

legacy (6th - 12th century CE) :

Sources :

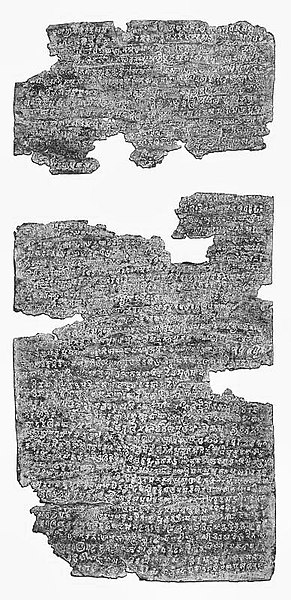

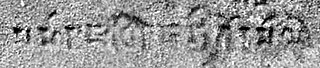

The Talagan copper scroll Ancient sources refer to the Alchons and associated groups ambiguously with various names, such as Hun in Indian texts, and Xionites in Greek texts. Xuanzang chronicled some of the later history of the Alchons.

Modern archeology has provided valuable insights into the history of the Alchons. The most significant cataloguing of the Alchon dynasty came in 1967 with Robert Göbl's analysis of the coinage of the "Iranian Huns". This work documented the names of a partial chronology of Alchon kings, beginning with Khingila. In 2012, the Kunsthistorisches Museum completed a reanalysis of previous finds together with a large number of new coins that appeared on the antiquities market during the Second Afghan Civil War, redefining the timeline and narrative of the Alchons and related peoples.

Talagan

copper scroll :

Rulers :

The rulers of the Alchons practiced skull deformation, as evidenced from their coins, a practice shared with the Huns that migrated into Europe. The names of the first Alchon rulers do not survive. Starting from 430 CE, names of Alchon kings survive on coins and religious inscriptions :

•

Anonymous kings

(400 - 430 CE)

Coinage :

An

early Alchon Huns coin based on a Sasanian design, with bust imitating

Sasanian king Shapur III. Only the legend "Alchono" appears

on the obverse in the Greco-Bactrian script.

Later

original coinage :

After their invasion of India the coins of the Alchon were numerous and varied, as they issued copper, silver and gold coins, sometimes roughly following the Gupta pattern. The Alchon empire in India must have been quite significant and rich, with the ability to issue a significant volume of gold coins.

Coinage :

Silver coin of Toramana in Western Gupta style, with the Gupta peacock and Brahmi legend on the reverse. Similar to the silver coin type of Skandgupt. On the obverse the date "52" is also inscribed. A modern image

Alchon Tamgha symbol on a coin of Khingila

Khingila with the word "Alchono" in Bactrian script and the Tamgha symbol on his coins

Silver drachm of Khingil (early portrait) without headdress, mid-late 5th century

Silver drachm of Khingil (mature portrait), Bactrian legend: "Khiggilo Alchono"

Silver drachm of Javukh, mid-late 5th century

Silver drachm of Meham legend: “Sahi meham", mid-late 5th century

Silver drachm of Lakhan, late 5th-early 6th centuries

Gold dinar of Adomano, Kushano-Sasanian style, mid-late 5th century

Silver drachm of Mihirkul, early-mid 6th century

Bronze drachm of Toraman II wearing trident crown, late-phase Gandharan style. mid 6th century

Silver stater of Toraman II, Kashmir style, mid-late 6th century

Bronze drachm of Naran-Narend (possibly Toramana II) wearing trident crown, late 6th century

Khingil as a young king, without headdress. Artificial cranial deformation clearly visible

Vishnu Nicolo Seal representing Vishnu with a worshipper (probably Mihirkul), 4th – 6th century CE. The inscription in cursive Bactrian reads: "Mihir, Vishnu and Shiv". British Museum Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg)

.jpg)