| ANTES (PEOPLE)

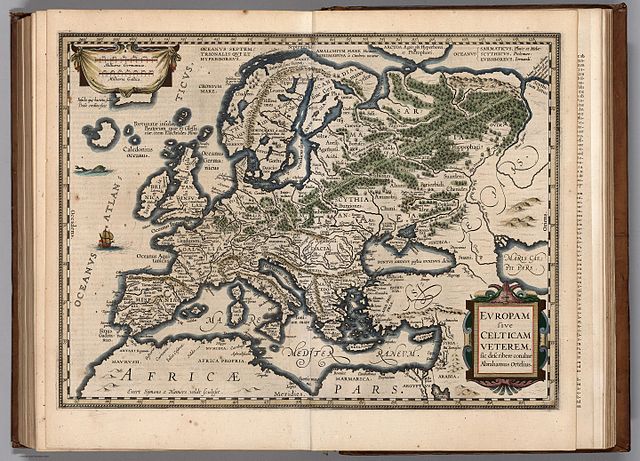

Archaeological cultures of the early 7th century identified with the early Slavs

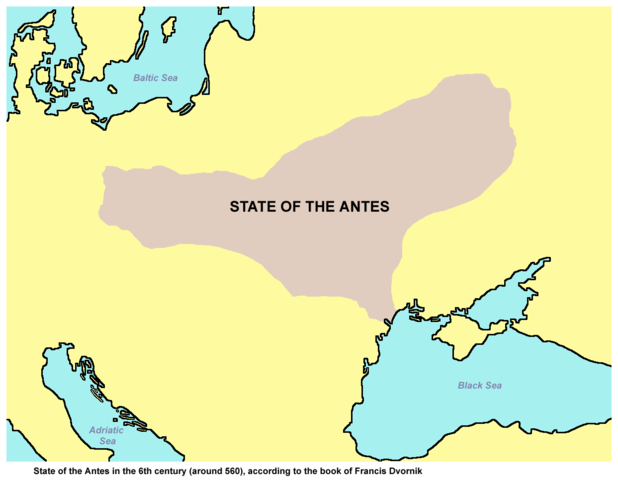

Antes near Pontic Olbia The Antes, or Antae, were an early East Slavic tribal polity of the 6th century CE. They lived on the lower Danube River, in the northwestern Black Sea region (present-day Moldova and central Ukraine), and in the regions around the Don River (in Middle and Southern Russia). They are commonly associated [by whom?] with the archaeological Penkovka culture.

First mentioned in the historical record in 518, the Antes invaded the Diocese of Thrace sometime between 533 and 545. Shortly thereafter, they became Byzantine foederati and received gold payments and a fort (named "Turris" - the Latin word turris means "a tower") somewhere north of the Danube at a strategically-important location to prevent hostile barbarians from invading Roman lands. Thus from 545 to the 580s, Antean soldiers fought in various Byzantine campaigns. The Pannonian Avars attacked the Antes at the beginning of the 7th century, when the Antes disappeared as a people.

Historiography :

Map of Slavic peoples of the 6th century (by Boris Rybakov) Scholars have studied the Antes since the late 18th century. Based on the literary evidence provided by Procopius (c. 500–560 CE) and Jordanes (fl. c. 551), the Antes, along with the Sklaveni and the Venethi, have long been viewed as the constituent proto-Slavic peoples ancestral to both medieval Slavic ethnicities and modern Slavic nations. At times, debate over the origins and the descendants of the Antes has been heated. The tribe has been variously regarded as the ancestors of, specifically, the Vyatichi or the Rus (from a medieval perspective), and, in terms of extant populations, of the Ukrainians versus other East Slavs. Additionally, South Slavic historians have regarded the Antes as the ancestors of the eastern South Slavs.

Ethnolinguistic

affinities :

Although the first unequivocal attestation of the Antes tribe is from the 6th century CE, scholars have tried to connect the Antes with a tribe rendered as An-tsai[verification needed] in a 2nd-century-BCE Chinese source (Hou Han-shu, 118, fol. 13r). [full citation needed] Pliny the Elder (Natural History VI, 35) mentions some Anti living near the shores of the Azov Sea, and inscriptions from the Kerch peninsula dating to the 3rd century CE bear the word antas. Based on documentation of "Sarmatian" tribes inhabiting the north Pontic region during the early centuries of the Common Era, presumed Iranic loanwords in Slavic languages, and Sarmatian "cultural borrowings" into the Penkovka culture, scholars such as Paul Robert Magocsi, Valentin Sedov, and John V.A. Fine, Jr. maintain earlier proposals by Soviet-era scholars such as Boris Rybakov, that the Antes were originally a Sarmatian–Alan frontier tribe that become Slavicized but preserved their name. Sedov argues that the ethnonym referred to the Slavic–Scythian–Sarmatian population living between the Dniester and Dnieper Rivers, and later to the related Slavic tribes who emerged from this Slavic–Iranian symbiosis.

However, more-recent perspectives view the tribal entities named by Graeco-Roman sources as fluctuant political formations that were, above all, etic categorizations based on ethnographic stereotypes rather than on first-hand, accurate knowledge of the barbarian language or "culture." Bartlomiej Szymon Szmoniewski argues that the Antes were not a "discrete, ethnically homogeneous entity" but rather "a highly complex political reality". Linguistically, contemporary evidence suggests that Proto-Slavic was the common language of an area that extended from the eastern Alps to the Black Sea and was spoken by peoples of varying ethnic backgrounds, including Slavs, provincial Romans, Germanic tribes (such as the Gepids and Lombards), and Turkic peoples (such as the Avars and Bulgars). It has further been proposed that the Sklaveni were not distinguished from others on the basis of language or culture but on that of military organization. Compared with the Avars, or 6th-century Goths, the Sklaveni were composed of numerous, smaller disunited groups, one of which – the Antai – became foederati constituted by a treaty.

History :

The Political Situation in S.E.E. ~ 520 AD – the post-Hun period and prior to Byzantine re-conquest of Gothic Italy

Map showing the State of the Antes in the 6th century (around 560), according to the book of Francis Dvornik

Early history :

Whatever the exact origins of the tribe, Jordanes and Procopius appear to suggest that the Antes were Slavic by the 5th century. In describing the lands of Scythia (Getica. 35), Jordanes states that "the populous race of the Venethi occupy a great expanse of land. Though their names are now dispersed amid various clans and places, yet they are chiefly called Sklaveni and Antes." Later, in describing the deeds of Ermanaric, the mythical Ostrogothic king, Jordanes writes that the Venethi "have now three names: Venethi, Antes, and Sklaveni" (Get. 119'). Finally, he describes a battle between the Antean king Boz and Ermanaric's successor Vinitharius after the latter's subjugation by the Huns. After initially defeating the Goths, the Antes lost the second battle, and Boz and 70 of his leading nobles were crucified (Get. 247). Scholars have traditionally taken the accounts of Jordanes as face-value evidence that the Sklaveni and (the bulk of the) Antes descended from the Venedi, a tribe known to historians such as Tacitus, Ptolemy, and Pliny the Elder since the 2nd century CE.

However, the utility of Getica as an accurate work of ethnography has been questioned. Walter Goffart, for example, argues that Getica created an entirely mythical story of Gothic and other peoples' origins. Florin Curta further argues that Jordanes had no real ethnographic knowledge of "Scythia," despite claims that he himself was a Goth and was born in Thrace. He borrowed heavily from earlier historians and only artificially linked the 6th-century Sklaveni and Antes with the earlier Venethi, who had otherwise long disappeared by that century. This anachronism was paired with a "modernizing narrative strategy" whereby Jordanes retold older events – the war between the Ostrogothic Vithimiris and the Alans – as a war between Vinitharius and the contemporary Antes. In any case, no 4th-century source mentions the Antes, and the "Ostrogoths" did not form until the 5th century – inside the Balkans.

Apart from the influence of older historians, Jordanes' narrative style was shaped by his polemical debate with his contemporary Procopius. While Jordanes linked the Sclaveni and Antes with the ancient Venedi, Procopius states that they were both once called Sporoi (Procopius. History of the Wars. VII 14.29).

Location in 6th century :

A

golden buckle from the Ödenkirche plot grave field at Keszthely-Fenékpuszta,

Zala County, Hungary; on the underside is the Greek inscription

ANTIKOY, "conqueror of the Antes".

6th

and 7th centuries :

Sometime between 533 and 545, the Antes invaded the Diocese of Thrace, enslaving many Romans and taking them north of the Danube to the Antean homelands. Indeed, numerous raids were conducted during this turbulent decade by numerous barbarian groups, including the Antes.

Shortly afterward, the Antes became Roman allies (after approaching the Romans) and were given gold payments and a fort named "Turris" somewhere north of the Danube at a strategically important location, in order to prevent hostile barbarians invading Roman lands. This was part of a larger set of alliances, including the Lombards, lifting pressure off the lower Danube and enabling forces to be diverted to Italy. Thus, in 545, Antean soldiers were fighting in Lucania against Ostrogoths, and in the 580s they attacked the settlements of the Sklavenes at the behest of the Romans. In 555 and 556, Dabragezas (of Antean origin) led the Roman fleet in Crimea against Persian positions.

The Antes remained Roman allies until their demise in the first decade of the 7th century. They were often involved in conflicts with the Avars, such as the war recorded by Menander the Guardsman (50, frg 5.3.17–21) in the 560s. In 602, in retaliation for a Roman attack on their Sklavene allies, the Avars sent their general Apsich to "destroy the nation of the Antes." Despite numerous defections to the Romans during the campaign, the Avar attack appears to have ended the Antean polity. They never again appear in sources, apart from the epithet Anticus in the imperial titulature in 612. Curta argues that the 602 attack on the Antes destroyed their political independence. However, based on the aforementioned attestation of Anticus, Georgios Kardaras rather argues that the disappearance of the Antes stemmed from the general collapse of the Scythian/lower Danubian limes they defended, ending their hegemony on the lower Danube. Other considered a remote connection between the Antes and the Primary Chronicle narrative in which is mentioned oppression of the Dulebes by the Avars, and the tradition recorded by Al-Masudi and Abraham ben Jacob that in ancient times the Walitaba (which some read as Walinana and identified with the Volhynians) were "the original, pure-blooded Saqaliba, the most highly honoured" and dominated the rest of the Slavic tribes, but due to "dissent" their "original organization was destroyed" and "the people divided into factions, each of them ruled by their own king", implying existence of a Slavic federation which perished after the attack of the Avars. Whatever the case, shortly after the collapse of the Danubian limes (more specifically, the tactical Roman withdrawal), the first evidence of Slavic settlement in northeastern Bulgaria begin to appear.

The Pereshchepina hoard, dating to the early 7th century, may be considered part of an Antean chieftain's treasury, although most researchers consider it to be the treasure of Khan Kubrat, the first ruler of Old Great Bulgaria.

Aftermath :

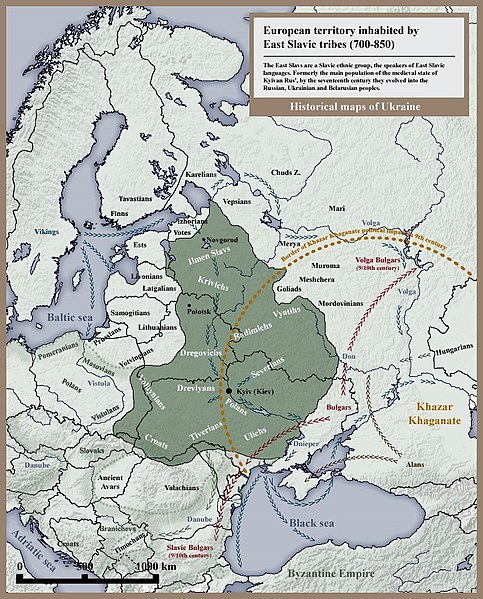

European territory inhabited by East Slavic tribes in 8th and 9th century Out of the old Antes federation, the following tribes evolved :

•

Croats, who were

scattered across Eastern Prykarpattia, Silesia and the upper Vistula

river, Eastern Bohemia, Saale, and Dalmatia

•

Ulichians, between

Dniester and Dnieper in the forest-steppe zone

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

_-_Germanic_gold_buckle,_Hungary.jpg)