| AVESTA The Avesta, is the primary collection of religious texts of Zoroastrianism, composed in Avestan language.

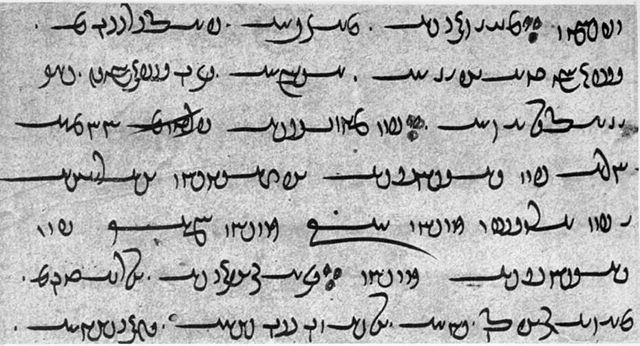

Writing a book in Avestan language The Avesta texts fall into several different categories, arranged either by dialect, or by usage. The principal text in the liturgical group is the Yasna, which takes its name from the Yasna ceremony, Zoroastrianism's primary act of worship, and at which the Yasna text is recited. The most important portion of the Yasna texts are the five Gathas, consisting of seventeen hymns attributed to Zoroaster himself. These hymns, together with five other short Old Avestan texts that are also part of the Yasna, are in the Old (or 'Gathic') Avestan language.

The remainder of the Yasna's texts are in Younger Avestan, which is not only from a later stage of the language, but also from a different geographic region.

Extensions to the Yasna ceremony include the texts of the Vendidad and the Visperad. The Visperad extensions consist mainly of additional invocations of the divinities (yazatas), while the Vendidad is a mixed collection of prose texts mostly dealing with purity laws. Even today, the Vendidad is the only liturgical text that is not recited entirely from memory. Some of the materials of the extended Yasna are from the Yashts, which are hymns to the individual yazatas. Unlike the Yasna, Visperad and Vendidad, the Yashts and the other lesser texts of the Avesta are no longer used liturgically in high rituals. Aside from the Yashts, these other lesser texts include the Nyayesh texts, the Gah texts, the Siroza, and various other fragments. Together, these lesser texts are conventionally called Khordeh Avesta or "Little Avesta" texts. When the first Khordeh Avesta editions were printed in the 19th century, these texts (together with some non-Avestan language prayers) became a book of common prayer for lay people.

The term Avesta is from the 9th/10th-century works of Zoroastrian tradition in which the word appears as Zoroastrian Middle Persian abestag, Book Pahlavi p'(y)st'k'. In that context, abestag texts are portrayed as received knowledge, and are distinguished from the exegetical commentaries (the zand) thereof. The literal meaning of the word abestag is uncertain; it is generally acknowledged to be a learned borrowing from Avestan, but none of the suggested etymologies have been universally accepted. The widely repeated derivation from *upa-stavaka is from Christian Bartholomae (Altiranisches Wörterbuch, 1904), who interpreted abestag as a descendant of a hypothetical reconstructed Old Iranian word for "praise-song" (Bartholomae: Lobgesang); that word is not actually attested in any text.

Historiography

:

A pre-Sasanian history of the Avesta, if it had one, is in the realm of legend and myth. The oldest surviving versions of these tales are found in the ninth to 11th century CE texts of Zoroastrian tradition (i.e. in the so-called "Pahlavi books"). The legends run as follows: The twenty-one nasks ("books") of the Avesta were created by Ahura Mazda and brought by Zoroaster to his patron Vishtasp (Denkard 4A, 3A). Supposedly, Vishtasp (Dk 3A) or another Kayanian, Daray (Dk 4B), then had two copies made, one of which was stored in the treasury, and the other in the royal archives (Dk 4B, 5).

Following Alexander's conquest, the Avesta was then supposedly destroyed or dispersed by the Greeks after they translated the scientific passages that they could make use of (AVN 7–9, Dk 3B, 8). Several centuries later, one of the Parthian emperors named Valaksh (one of the Vologases) supposedly then had the fragments collected, not only of those that had previously been written down, but also of those that had only been orally transmitted (Dk 4C).

The Denkard also transmits another legend related to the transmission of the Avesta. In that story, credit for collation and recension is given to the early Sasanian-era priest Tansar (high priest under Ardashir I, r. 224–242 CE, and Shapur I, 240/242–272 CE), who had the scattered works collected, and of which he approved only a part as authoritative (Dk 3C, 4D, 4E). Tansar's work was then supposedly completed by Adurbad Mahraspandan (high priest of Shapur II, r. 309–379 CE) who made a general revision of the canon and continued to ensure its orthodoxy (Dk 4F, AVN 1.12–1.16). A final revision was supposedly undertaken in the 6th century CE under Khosrow I (Dk 4G).

In the early 20th century, the legend of the Parthian-era collation engendered a search for a 'Parthian archetype' of the Avesta. In the theory of Friedrich Carl Andreas (1902), the archaic nature of the Avestan texts was assumed to be due to preservation via written transmission, and unusual or unexpected spellings in the surviving texts were assumed to be reflections of errors introduced by Sasanian-era transcription from the Aramaic alphabet-derived Pahlavi scripts. The search for the 'Arsacid archetype' was increasingly criticized in the 1940s and was eventually abandoned in the 1950s after Karl Hoffmann demonstrated that the inconsistencies noted by Andreas were actually due to unconscious alterations introduced by oral transmission. Hoffmann identifies these changes to be due in part to modifications introduced through recitation; in part to influences from other Iranian languages picked up on the route of transmission from somewhere in eastern Iran (i.e. Central Asia) via Arachosia and Sistan through to Persia; and in part due to the influence of phonetic developments in the Avestan language itself.

The legends of an Arsacid-era collation and recension are no longer taken seriously. It is now certain that for most of their long history the Avesta's various texts were handed down orally, and independently of one another, and that it was not until around the 5th or 6th century CE that they were committed to written form. However, during their long history, only the Gathic texts seem to have been memorized (more or less) exactly. The other less sacred works appear to have been handed down in a more fluid oral tradition, and were partly composed afresh with each generation of poet-priests, sometimes with the addition of new material. The Younger Avestan texts are therefore composite works, with contributions from several different authors over the course of several hundred years.

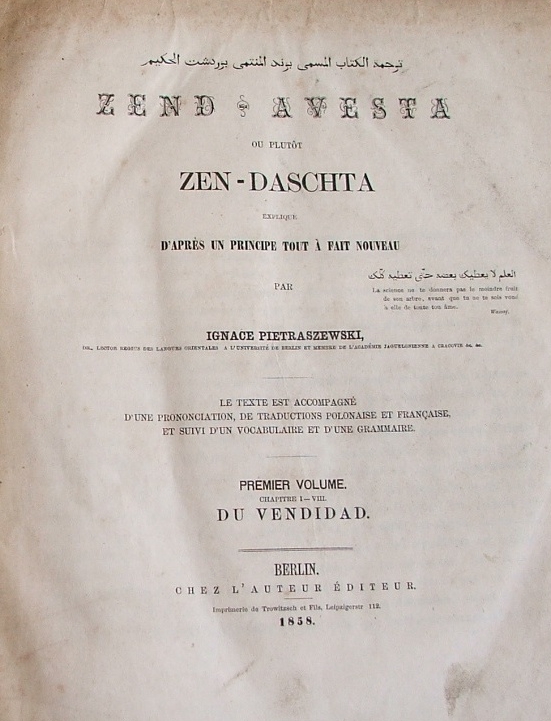

The texts became available to European scholarship comparatively late, thus the study of Zoroastrianism in Western countries dates back to only the 18th century. Abraham Hyacinthe Anquetil-Duperron travelled to India in 1755, and discovered the texts among Indian Zoroastrian (Parsi) communities. He published a set of French translations in 1771, based on translations provided by a Parsi priest. Anquetil-Duperron's translations were at first dismissed as a forgery in poor Sanskrit, but he was vindicated in the 1820s following Rasmus Rask's examination of the Avestan language (A Dissertation on the Authenticity of the Zend Language, Bombay, 1821). Rask also established that Anquetil-Duperron's manuscripts were a fragment of a much larger literature of sacred texts. Anquetil-Duperron's manuscripts are at the Bibliothèque nationale de France ('P'-series manuscripts), while Rask's collection now lies in the Royal Library, Denmark ('K'-series). Other large Avestan language manuscript collections are those of the British Museum ('L'-series), the K. R. Cama Oriental Library in Mumbai, the Meherji Rana library in Navsari, and at various university and national libraries in Europe.

Structure

and content :

According to the Denkard, the 21 nasks (books) mirror the structure of the 21-word-long Ahuna Vairya prayer: each of the three lines of the prayer consists of seven words. Correspondingly, the nasks are divided into three groups, of seven volumes per group. Originally, each volume had a word of the prayer as its name, which so marked a volume's position relative to the other volumes. Only about a quarter of the text from the nasks has survived until today.

The contents of the Avesta are divided topically (even though the organization of the nasks is not), but these are not fixed or canonical. Some scholars prefer to place the categories in two groups, one liturgical, and the other general. The following categorization is as described by Jean Kellens (see bibliography, below).

The Yasna :

The Yasna (from yazišn "worship, oblations", cognate with Sanskrit yagña), is the primary liturgical collection, named after the ceremony at which it is recited. It consists of 72 sections called the Ha-iti or Ha. The 72 threads of lamb's wool in the Kushti, the sacred thread worn by Zoroastrians, represent these sections. The central portion of the Yasna is the Gathas, the oldest and most sacred portion of the Avesta, believed to have been composed by Zarathushtra (Zoroaster) himself.

The Gathas are structurally interrupted by the Yasna Haptanghaiti ("seven-chapter Yasna"), which makes up chapters 35–42 of the Yasna and is almost as old as the Gathas, consists of prayers and hymns in honor of Ahura Mazda, the Yazatas, the Fravashi, Fire, Water, and Earth. The younger Yasna, though handed down in prose, may once have been metrical, as the Gathas still are.

The

Visperad :

The Visperad collection has no unity of its own, and is never recited separately from the Yasna.

The

Vendidad :

The first fargard is a dualistic creation myth, followed by the description of a destructive winter on the lines of the Flood myth. The second fargard recounts the legend of Yima. The remaining fargards deal primarily with hygiene (care of the dead in particular) [fargard 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 16, 17, 19] as well as disease and spells to fight it [7, 10, 11, 13, 20, 21, 22]. Fargards 4 and 15 discuss the dignity of wealth and charity, of marriage and of physical effort, and the indignity of unacceptable social behaviour such as assault and breach of contract, and specify the penances required to atone for violations thereof.

The Vendidad is an ecclesiastical code, not a liturgical manual, and there is a degree of moral relativism apparent in the codes of conduct. The Vendidad's different parts vary widely in character and in age. Some parts may be comparatively recent in origin although the greater part is very old.

The Vendidad, unlike the Yasna and the Visparad, is a book of moral laws rather than the record of a liturgical ceremony. However, there is a ceremony called the Vendidad, in which the Yasna is recited with all the chapters of both the Visparad and the Vendidad inserted at appropriate points. This ceremony is only performed at night.

The Yashts :

The Yashts (from yešti, "worship by praise") are a collection of 21 hymns, each dedicated to a particular divinity or divine concept. Three hymns of the Yasna liturgy that "worship by praise" are—in tradition—also nominally called yashts, but are not counted among the Yasht collection since the three are a part of the primary liturgy. The Yashts vary greatly in style, quality and extent. In their present form, they are all in prose but analysis suggests that they may at one time have been in verse.

The

Siroza :

The Siroza is never recited as a whole, but is a source for individual sentences devoted to particular divinities, to be inserted at appropriate points in the liturgy depending on the day and the month.

The

Nyayeshes :

The

Gahs :

The

Afrinagans :

Fragments

:

Other

Zoroastrian religious texts :

The most notable among the Middle Persian texts are the Denkard ("Acts of Religion"), dating from the ninth century; the Bundahishn ("Primordial Creation"), finished in the eleventh or twelfth century, but containing older material; the Mainog-i-Khirad ("Spirit of Wisdom"), a religious conference on questions of faith; and the Book of Arda Viraf, which is especially important for its views on death, salvation and life in the hereafter. Of the post-14th century works (all in New Persian), only the Sad-dar ("Hundred Doors, or Chapters"), and Revayats (traditional treatises) are of doctrinal importance. Other texts such as Zartushtnamah ("Book of Zoroaster") are only notable for their preservation of legend and folklore. The Aogemadaeca "we accept," a treatise on death is based on quotations from the Avesta.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |