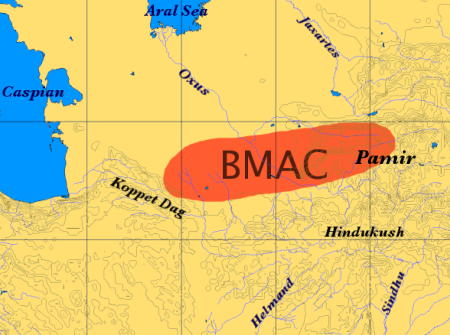

| BACTRIA - MARGIANA ARCHAEOLOGICAL COMPLEX

The extent of the BMAC (according to the Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture)

Archaeological cultures associated with Indo-Iranian migrations (after EIEC). The Andronovo, BMAC and Yaz cultures have often been associated with Indo-Iranian migrations. The GGC (Swat), Cemetery H, Copper Hoard and PGW cultures are candidates for cultures associated with Indo-Aryan migrations.

The Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex (short BMAC), also known as the Oxus civilization, is the modern archaeological designation for a Bronze Age civilization of Central Asia, dated to c. 2400–1900 BC in its urban phase or Integration Era, located in present-day northern Afghanistan, eastern Turkmenistan, southern Uzbekistan and western Tajikistan, centred on the upper Amu Darya (Oxus River) in Bactria, and at Murghab river delta in Margiana. Its sites were discovered and named by the Soviet archaeologist Viktor Sarianidi (1976). Bactria was the Greek name for the area of Bactra (modern Balkh), in what is now northern Afghanistan, and Margiana was the Greek name for the Persian satrapy of Marguš, the capital of which was Merv, in modern-day southeastern Turkmenistan.

Sarianidi's excavations from the late 1970s onward revealed numerous monumental structures in many sites, fortified by impressive walls and gates. Reports on the BMAC were mostly confined to Soviet journals, a journalist from The New York Times wrote in 2001 that he thought that during the years of the Soviet Union, the findings were largely unknown to the West until Sarianidi's work began to be translated in the 1990s, however there were already some publications by Soviet authors, like Masson, Sarianidi, Atagarryev, and Berdiev, in Western World since the 1970s at least.

Development

:

Female statuette, an example of a "Bactrian princess"; late 3rd–early 2nd millennium BC; steatite or chlorite and alabaster; 9 × 9.4 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Regionalization Era :

Altyn-Depe location on the modern Middle East map as well as location of other Eneolithic cultures (Harappa and Mohenjo-daro) Major chalcolithic settlements sprang up at Kara-Depe and Namazga-Depe. In addition, there were smaller settlements at Anau, Dashlyji, and Yassy-depe. Settlements similar to the early level at Anau also appeared further east– in the ancient delta of the river Tedzen, the site of the Geoksiur Oasis. About 3500 BC, the cultural unity of the area split into two pottery styles: colourful in the west (Anau, Kara-Depe and Namazga-Depe) and more austere in the east at Altyn-Depe and the Geoksiur Oasis settlements. This may reflect the formation of two tribal groups. It seems that around 3000 BC, people from Geoksiur migrated into the Murghab delta (where small, scattered settlements appeared) and reached further east into the Zerafshan Valley in Transoxiana. In both areas pottery typical of Geoksiur was in use. In Transoxiana they settled at Sarazm near Pendjikent. To the south the foundation layers of Shahr-i Shokhta on the bank of the Helmand river in south-eastern Iran contained pottery of the Altyn-Depe and Geoksiur type. Thus the farmers of Iran, Turkmenistan and Afghanistan were connected by a scattering of farming settlements.

Late

Regionalization Era :

Integration

Era :

Material culture :

Bird-headed man with snakes; 2000-1500 BC; bronze; 7.30 cm; from Northern Afghanistan; Los Angeles County Museum of Art (USA)

Agriculture and economy :

Models of two-wheeled carts from c. 3000 BC found at Altyn-Depe are the earliest evidence of wheeled transport in Central Asia, though model wheels have come from contexts possibly somewhat earlier. Judging by the type of harness, carts were initially pulled by oxen, or a bull. However camels were domesticated within the BMAC. A model of a cart drawn by a camel of c. 2200 BC was found at Altyn-Depe.

Art

:

Female figurine of the "Bactrian princess" type; between 3rd millennium and 2nd millennium BC; chlorite mineral group (dress and headdresses) and limestone (face and neck); height: 17.3 cm, width: 16.1 cm; Louvre

Axe with eagle-headed demon & animals; late 3rd millennium-early 2nd millennium BC; gilt silver; length: 15 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Camel figurine; late 3rd–early 2nd millennium BCE; copper alloy; 8.89 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Monstrous male figure; late 3rd–early 2nd millennium BC; chlorite, calcite, gold and iron; height: 10.1 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Axe head; late 3rd–early 2nd millennium BC; copper alloy; height: 2.8 cm, length: 7.2 cm, thickness: 1.8 cm, weight: 82.5 g; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Female figurine of the "Bactrian princess" type; between 3rd millennium and 2nd millennium BC; grey chlorite (dress and headdresses) and calcite (face); Barbier-Mueller Museum (Geneva, Switzerland)

Female figurine of the "Bactrian princess" type; between 3rd millennium and 2nd millennium BC; grey chlorite (dress and headdresses) and calcite (face); Barbier-Mueller Museum

Beaker with birds on the rim; late 3rd–early 2nd millennium BC; electrum; height: 12 cm, width: 13.3 cm, depth: 4.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Handled weight; late 3rd–early 2nd millennium BC; chlorite; 25.08 x 19.69 x 4.45 cm; Los Angeles County Museum of Art (USA)

Female figurine of the "Bactrian princess" type; 2500-1500; chlorite (dress and headdresses) and limestone (head, hands and a leg); height: 13.33 cm; Los Angeles County Museum of Art (USA)

Vessel with gilloche pattern; 2000-1500; chlorite; 3.33 x 6.67 x 3.81 cm; Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Female figurine of the "Bactrian princess" type; 2nd millennium BC; chlorite and calcite; Louvre Architecture

:

The people of the BMAC culture were very proficient at working in a variety of metals including bronze, copper, silver, and gold. This is attested through the many metal artefacts found throughout the sites.

Extensive irrigation systems have been discovered at the Geoksiur Oasis.

Writing

:

Interactions

with other cultures :

The relationship between Altyn-Depe and the Indus Valley seems to have been particularly strong. Among the finds there were two Harappan seals and ivory objects. The Harappan settlement of Shortugai in Northern Afghanistan on the banks of the Amu Darya probably served as a trading station.

There is evidence of sustained contact between the BMAC and the Eurasian steppes to the north, intensifying c. 2000 BC. In the delta of the Amu Darya where it reaches the Aral Sea, its waters were channelled for irrigation agriculture by people whose remains resemble those of the nomads of the Andronovo culture. This is interpreted as nomads settling down to agriculture, after contact with the BMAC, known as the Tazabagyab culture. About 1900 BC, the walled BMAC centres decreased sharply in size. Each oasis developed its own types of pottery and other objects. Also pottery of the Tazabagyab-Andronovo culture to the north appeared widely in the Bactrian and Margian countryside. Many BMAC strongholds continued to be occupied and Tazabagyab-Andronovo coarse incised pottery occurs within them (along with the previous BMAC pottery) as well as in pastoral camps outside the mudbrick walls. In the highlands above the Bactrian oases in Tajikistan, kurgan cemeteries of the Vaksh and Bishkent type appeared with pottery that mixed elements of the late BMAC and Tazabagyab-Andronovo traditions. In southern Bactrian sites like Sappali Tepe too, increasing links with the Andronovo culture are seen. During the period 1700 - 1500 BCE, metal artifacts from Sappali Tepe derive from the Tazabagyab-Andronovo culture.

Relationship

with Indo-Iranians :

A significant section of the archaeologists are more inclined to see the culture as begun by farmers in the Near Eastern Neolithic tradition, but infiltrated by Indo-Iranian speakers from the Andronovo culture in its late phase, creating a hybrid. In this perspective, Proto-Indo-Aryan developed within the composite culture before moving south into the Indian subcontinent.

The Andronovo, BMAC and Yaz cultures have often been associated with Indo-Iranian migrations. As James P. Mallory phrased it :

It has become increasingly clear that if one wishes to argue for Indo-Iranian migrations from the steppe lands south into the historical seats of the Iranians and Indo-Aryans that these steppe cultures were transformed as they passed through a membrane of Central Asian urbanism. The fact that typical steppe wares are found on BMAC sites and that intrusive BMAC material is subsequently found further to the south in Iran, Afghanistan, Nepal, India and Pakistan, may suggest then the subsequent movement of Indo-Iranian-speakers after they had adopted the culture of the BMAC.

According to recent studies BMAC was not a primary contributor to later South-Asian genetics.

Possible

evidence for a BMAC substratum in Indo-Iranian :

BMAC can be connected to the Das tribe of Indians. To know more Click here.

Genetics

:

A follow-up study by Narasimhan and co-authors (2019) suggested the primary BMAC population largely derived from preceding local Copper Age peoples who were in turn related to prehistoric farmers from the Iranian plateau and to a lesser extent early Anatolian farmers and hunter-gatherers from Western Siberia, and they did not contribute substantially to later populations further south in the Indus Valley. They found no evidence that the samples extracted from the BMAC sites derived any part of their ancestry from Yamnaya culture people, who are seen as Proto-Indo-Europeans in the Kurgan hypothesis, the most influential theory on the Proto-Indo-European homeland.

Sites

:

•

Dashli, Jowzjan

province

•

Altyndepe

•

Ayaz Kala

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org |

.jpg)