HURRIANS

The

approximate area of Hurrian settlement in the Middle Bronze Age

is shown in purple

Regions

with significant populations : Near East

Languages : Hurrian

Religion : Hurrian religion

The

Hurrians (also called Hari, Khurrites, Hourri, Churri, Hurri or

Hurriter) were a people of the Bronze Age Near East. They spoke

a Hurro-Urartian language called Hurrian and lived in Anatolia,

Syria and Northern Mesopotamia. The largest and most influential

Hurrian nation was the kingdom of Mitanni, its ruling class perhaps

being Indo-Iranian speakers.

The

population of the Indo-European-speaking Hittite Empire in Anatolia

included a large population of Hurrians, and there is significant

Hurrian influence in Hittite mythology. By the Early Iron Age, the

Hurrians had been assimilated with other peoples. Their remnants

were subdued by a related people that formed the state of Urartu.

The

present-day Armenians are an amalgam of the Indo-European groups

with the Hurrians and Urartians.

Language

:

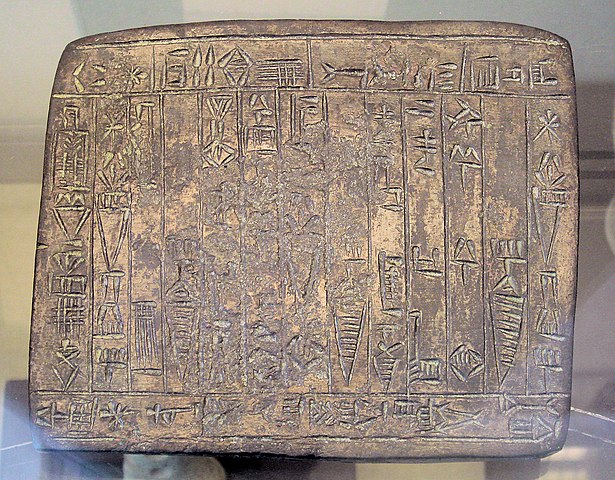

Incense burner. Hurrian period, 1300-1000 BC. From Tell

Basmosian (also Tell Bazmusian), modern-day Lake Dukan, Iraq. Currently

displayed in Erbil Civilization Museum

The

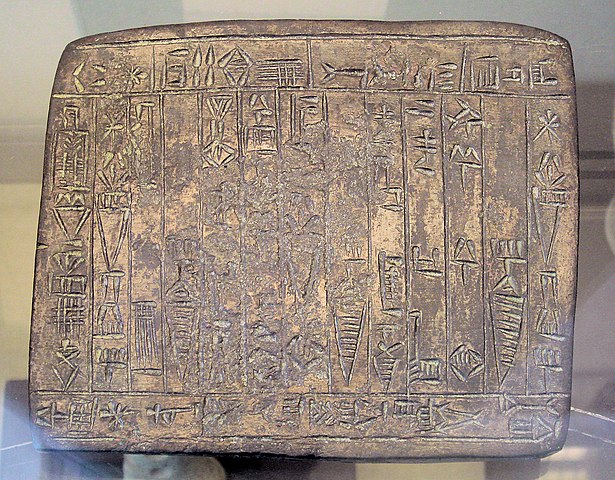

Louvre lion and accompanying stone tablet bearing the earliest known

text in Hurrian

The Hurrian language is closely related to the Urartian language,

the language of the ancient kingdom of Urartu. Together they form

the Hurro-Urartian language family. The external connections of

the Hurro-Urartian languages are disputed. There exist various proposals

for a genetic relationship to other language families (e.g. the

Northeast Caucasian languages), but none of these are generally

accepted.

From

the 21st century BCE to the late 18th century BCE, Assyria controlled

colonies in Anatolia, and the Hurrians, like the Hattians or Lullubis,

adopted the Assyrian Akkadian cuneiform script for their own language

about 2000 BCE. Texts in the Hurrian language in cuneiform have

been found at Hattusa, Ugarit (Ras Shamra), as well as in one of

the longest of the Amarna letters, written by King Tushratta of

Mitanni to Pharaoh Amenhotep III. It was the only long Hurrian text

known until a multi-tablet collection of literature in Hurrian with

a Hittite translation was discovered at Hattusa in 1983.

History

:

Middle Bronze Age :

Hurrian names occur sporadically in northwestern Mesopotamia and

the area of Kirkuk in modern Iraq by the Middle Bronze Age. Their

presence was attested at Nuzi, Urkesh and other sites. They eventually

infiltrated and occupied a broad arc of fertile farmland stretching

from the Khabur River valley in the west to the foothills of the

Zagros Mountains in the east. I. J. Gelb and E. A. Speiser believed

East Semitic speaking Assyrians/Subarians had been the linguistic

and ethnic substratum of northern Mesopotamia since earliest times,

while Hurrians were merely late arrivals. However, Subarians are

now believed to have been a Hurrian, or at least a Hurro-Urartian,

people.

Urkesh

:

Foundation

tablet. Dedication to God Nergal by Hurrian king Atalshen, king

of Urkish and Nawar, Habur Bassin, circa 2000 BC. Louvre Museum

AO 5678

"Of Nergal the lord of Hawalum, Atal-shen, the caring shepherd,

the king of Urkesh and Nawar, the son of Sadar-mat the king, is

the builder of the temple of Nergal, the one who overcomes opposition.

Let Shamash and Ishtar destroy the seeds of whoever removes this

tablet. Shaum-shen is the craftsman."

The Khabur River valley became the heart of the Hurrian lands for

a millennium. The first known Hurrian kingdom emerged around the

city of Urkesh (modern Tell Mozan) during the third millennium BCE.

There is evidence that they were initially allied with the east

Semitic Akkadian Empire of Mesopotamia, indicating they had a firm

hold on the area by the reign of Naram-Sin of Akkad (c. 2254–2218

BCE). This region hosted other rich cultures. The city-state of

Urkesh had some powerful neighbors. At some point in the early second

millennium BCE, the Northwest Semitic speaking Amorite kingdom of

Mari to the south subdued Urkesh and made it a vassal state. In

the continuous power struggles over Mesopotamia, another Amorite

dynasty had usurped the throne of the Old Assyrian Empire, which

had controlled colonies in Hurrian, Hattian and Hittite regions

of eastern Anatolia since the 21st century BCE. The Assyrians then

made themselves masters over Mari and much of north east Amurru

(Syria) in the late 19th and early 18th centuries BCE. Shubat-Enlil

(modern Tell Leilan), was made the capital of this Old Assyrian

empire by Shamshi Adad I at the expense of the earlier capital of

Assur.

Yamhad

:

The Hurrians also migrated further west in this period. By 1725

BCE they are found also in parts of northern Syria, such as Alalakh.

The mixed Amorite–Hurrian kingdom of Yamhad is recorded as

struggling for this area with the early Hittite king Hattusilis

I around 1600 BCE. Hurrians also settled in the coastal region of

Adaniya in the country of Kizzuwatna, southern Anatolia. Yamhad

eventually weakened vis-a-vis the powerful Hittites, but this also

opened Anatolia for Hurrian cultural influences. The Hittites were

influenced by both the Hurrian and Hattian cultures over the course

of several centuries.

Late

Bronze Age :

Mitanni :

The Indo-European Hittites continued expanding south after the defeat

of Yamhad. The army of the Hittite king Mursili I made its way to

Babylon (by then a weak and minor state) and sacked the city. The

destruction of the Babylonian kingdom, the presence of unambitious

or isolationist kings in Assyria, as well as the destruction of

the kingdom of Yamhad, helped the rise of another Hurrian dynasty.

The first ruler was a legendary king called Kirt who founded the

kingdom of Mitanni (known also as Hanigalbat/?anigalbat by the Assyrians,

and to the Egyptians as nhrn) around 1500 BCE.

Mitanni

gradually grew from the region around the Khabur valley and was

perhaps the most powerful kingdom of the Near East in c. 1475–1365

BCE, after which it was eclipsed and eventually destroyed by the

Middle Assyrian Empire.

Some

theonyms, proper names and other terminology of the Mitanni exhibit

an Indo-Aryan superstrate, suggesting that an Indo-Aryan elite imposed

itself over the Hurrian population in the course of the Indo-Aryan

expansion. (See Mitanni-Aryan.)

Arrapha

:

Another Hurrian kingdom also benefited from the demise of Babylonian

power in the sixteenth century BCE. Hurrians had inhabited the region

northeast of the river Tigris, around the modern Kirkuk. This was

the kingdom of Arrapha. Excavations at Yorgan Tepe, ancient Nuzi,

proved this to be one of the most important sites for our knowledge

about the Hurrians. Hurrian kings such as Ithi-Teshup and Ithiya

ruled over Arrapha, yet by the mid-fifteenth century BCE they had

become vassals of the Great King of Mitanni. The kingdom of Arrapha

itself was destroyed by the Assyrians in the mid 14th century BCE

and thereafter became an Assyrian city.

Bronze

Age collapse :

By the 13th century BCE all of the Hurrian states had been vanquished

by other peoples, with the Mitanni kingdom destroyed by Assyria.

The heartlands of the Hurrians, the Khabur river valley and south

eastern Anatolia, became provinces of the Middle Assyrian Empire

(1366–1020 BCE) which came to rule much of the Near East and

Asia Minor. It is not clear what happened to these early Hurrian

people at the end of the Bronze Age. Some scholars have suggested

that Hurrians lived on in the country of Nairi north of Assyria

during the early Iron Age, before this too was conquered by Assyria.

The Hurrian population of northern Syria in the following centuries

seems to have given up their language in favor of the Assyrian dialect

of Akkadian, and later, Aramaic.

Urartu

:

However, a power vacuum was to allow a new and powerful state whose

rulers spoke Urartian, similar to old Hurrian, to arise. The Middle

Assyrian Empire, after destroying the Hurro-Mitanni Empire, the

Hittite Empire, defeating the Phrygians and Elamites, conquering

Babylon, the Arameans of Syria, northern Ancient Iran and Canaan

and forcing the Egyptians out of much of the near east, itself went

into a century of relative decline from the latter part of the 11th

century BCE. The Urartians were thus able to impose themselves around

Lake Van and Mount Ararat, forming the powerful Kingdom of Urartu.

During the 11th and 10th centuries BCE, the kingdom eventually encompassed

a region stretching from the Caucasus Mountains in the north, to

the borders of northern Assyria and northern Ancient Iran in the

south, and controlled much of eastern Anatolia.

Assyria

began to once more expand from circa. 935 BCE, and Urartu and Assyria

became fierce rivals. Urartu successfully repelled Assyrian expansionism

for a time, however from the 9th to 7th century BCE it progressively

lost territory to Assyria. It was to survive until the 7th century

BCE, by which time it was conquered fully into the Neo Assyrian

Empire (911–605 BCE).

The

Assyrian Empire collapsed from 620 to 605 BCE, after a series of

brutal internal civil wars weakened it to such an extent that a

coalition of its former vassals; the Medes, Persians, Babylonians,

Chaldeans, Scythians and Cimmerians were able to attack and gradually

destroy it. Urartu was ravaged by marauding Indo-European speaking

Scythian and Cimmerian raiders during this time, with its vassal

king (together with the king of neighbouring Lydia) vainly pleading

with the beleaguered Assyrian king for help. After the fall of Assyria,

Urartu came under the control of the Median Empire and then its

successor Persian Empire during the 6th century BCE.

During

the 2nd millennium BC a new wave of Indo-European speakers migrated

over the Caucasus into Urartian lands, these being the Armenians.

An alternate theory suggests that Armenians were tribes indigenous

to the northern shores of Lake Van or Urartu's northern periphery

(possibly as the Hayasans, Etuini, and/or Diauehi, all of whom are

known only from references left by neighboring peoples such Hittites,

Urartians, and Assyrians). This theory is supported by genetic and

archaeological evidence, which is suggestive of an Indo-European

presence in Armenia and eastern Turkey by the end of the 3rd millennium

BCE.

It

is argued that proto-Armenian came into contact with Urartian at

an early date (3rd or 2nd millennium BC), before the formation of

the Urartian kingdom. While the Urartian language was used by the

royal elite, the population they ruled may have been multi-lingual,

and some of these peoples would have spoken Armenian.

In

the 6th century BCE the region became part of the Armenian Orontid

Dynasty. The Hurro-Urartians seem to have disappeared from history

around this time, almost certainly being absorbed into the Indo-European

Armenian population.

Culture

and society :

Knowledge of Hurrian culture relies on archaeological excavations

at sites such as Nuzi and Alalakh as well as on cuneiform tablets,

primarily from Hattusa (Boghazköy), the capital of the Hittites,

whose civilization was greatly influenced by the Hurrians. Tablets

from Nuzi, Alalakh, and other cities with Hurrian populations (as

shown by personal names) reveal Hurrian cultural features even though

they were written in Akkadian. Hurrian cylinder seals were carefully

carved and often portrayed mythological motifs. They are a key to

the understanding of Hurrian culture and history.

Ceramic

ware :

The Hurrians were masterful ceramists. Their pottery is commonly

found in Mesopotamia and in the lands west of the Euphrates; it

was highly valued in distant Egypt, by the time of the New Kingdom.

Archaeologists use the terms Khabur ware and Nuzi ware for two types

of wheel-made pottery used by the Hurrians.

Khabur

ware is characterized by reddish painted lines with a geometric

triangular pattern and dots, while Nuzi ware has very distinctive

forms, and are painted in brown or black.

Metallurgy

:

The Hurrians had a reputation in metallurgy. It is proposed that

the Sumerian term for "coppersmith" tabira/tibira was

borrowed from Hurrian, which would imply an early presence of the

Hurrians way before their first historical mention in Akkadian sources.

Copper was traded south to Mesopotamia from the highlands of Anatolia.

The Khabur Valley had a central position in the metal trade, and

copper, silver and even tin were accessible from the Hurrian-dominated

countries Kizzuwatna and Ishuwa situated in the Anatolian highland.

Gold was in short supply, and the Amarna letters inform us that

it was acquired from Egypt. Not many examples of Hurrian metal work

have survived, except from the later Urartu. Some small fine bronze

lion figurines were discovered at Urkesh.

Horse

culture :

The Mitanni were closely associated with horses. The name of the

country of Ishuwa, which might have had a substantial Hurrian population,

meant "horse-land" (it is also suggested the name may

have Anatolian or proto-Armenian roots). A text discovered at Hattusa

deals with the training of horses. The man who was responsible for

the horse-training was a Hurrian called Kikkuli. The terminology

used in connection with horses contains many Indo-Aryan loan-words

(Mayrhofer, 1974).

Music

:

Among the Hurrian texts from Ugarit are the oldest known instances

of written music, dating from c. 1400 BCE. Among these fragments

are found the names of four Hurrian composers, Tapšihuni, Puhiya(na),

Ur?iya, and Ammiya.

Religion

:

The Hurrian culture made a great impact on the religion of the Hittites.

From the Hurrian cult centre at Kummanni in Kizzuwatna Hurrian religion

spread to the Hittite people. Syncretism merged the Old Hittite

and Hurrian religions. Hurrian religion spread to Syria, where Baal

became the counterpart of Teshub. The later kingdom of Urartu also

venerated gods of Hurrian origin. The Hurrian religion, in different

forms, influenced the entire ancient Near East, except ancient Egypt

and southern Mesopotamia.

Hurrian incense container

The

Hittite gods Teshub and Hebat, chamber A, Yazilikaya, Hittite rock

sanctuary, Turkey

The main gods in the Hurrian pantheon were :

•

Teshub, Teshup;

the mighty weather god.

• Hebat,

Hepa; his wife, the mother goddess, regarded as the Sun goddess

among the Hittites, drawn from the deified Sumerian queen Kubaba.

• Sharruma,

or Sarruma, Šarruma; their son.

• Kumarbi;

the ancient father of Teshub; his home as described in mythology

is the city of Urkesh.

• Shaushka,

or Shawushka, Šauska; was the Hurrian counterpart of Assyrian

Ishtar, and a goddess of fertility, war and healing.

• Shimegi,

Šimegi; the sun god.

• Kushuh,

Kušuh; the moon god. Symbols of the sun and the crescent moon

appear joined together in the Hurrian iconography.

• Nergal;

a Babylonian deity of the netherworld, whose Hurrian name is unknown.

• Ea;

was also Babylonian in origin, and may have influenced Canaanite

El, and also Yam, God of the Sea and River.

Hurrian cylinder seals often depict mythological creatures such

as winged humans or animals, dragons and other monsters. The interpretation

of these depictions of gods and demons is uncertain. They may have

been both protective and evil spirits. Some is reminiscent of the

Assyrian shedu.

The

Hurrian gods do not appear to have had particular "home temples",

like in the Mesopotamian religion or Ancient Egyptian religion.

Some important cult centres were Kummanni in Kizzuwatna, and Hittite

Yazilikaya. Harran was at least later a religious centre for the

moon god, and Shauskha had an important temple in Nineve, when the

city was under Hurrian rule. A temple of Nergal was built in Urkesh

in the late third millennium BCE. The town of Kahat was a religious

centre in the kingdom of Mitanni.

The

Hurrian myth "The Songs of Ullikummi", preserved among

the Hittites, is a parallel to Hesiod's Theogony; the castration

of Uranus by Cronus may be derived from the castration of Anu

by Kumarbi, while Zeus's overthrow of Cronus and Cronus's regurgitation

of the swallowed gods is like the Hurrian myth of Teshub and Kumarbi.

It has been argued that the worship of Attis drew on Hurrian myth.

The Phrygian goddess Cybele would then be the counterpart of the

Hurrian goddess Hebat.

Urbanism

:

The Hurrian urban culture was not represented by a large number

of cities. Urkesh was the only Hurrian city in the third millennium

BCE. In the second millennium BCE we know a number of Hurrian cities,

such as Arrapha, Harran, Kahat, Nuzi, Taidu and Washukanni –

the capital of Mitanni.

Although

the site of Washukanni, alleged to be at Tell Fakhariya, is not

known for certain, no tell (city mound) in the Khabur Valley much

exceeds the size of 1 square kilometer (250 acres), and the majority

of sites are much smaller. The Hurrian urban culture appears to

have been quite different from the centralized state administrations

of Assyria and ancient Egypt. An explanation could be that the feudal

organization of the Hurrian kingdoms did not allow large palace

or temple estates to develop.

Archaeology

:

Hurrian settlements are distributed over three modern countries,

Iraq, Syria and Turkey. The heart of the Hurrian world is bisected

by the modern border between Syria and Turkey. Several sites are

situated within the border zone, making access for excavations problematic.

A threat to the ancient sites are the many dam projects in the Euphrates,

Tigris and Khabur valleys. Several rescue operations have already

been undertaken when the construction of dams put entire river valleys

under water.

The

first major excavations of Hurrian sites in Iraq and Syria began

in the 1920s and 1930s. They were led by the American archaeologist

Edward Chiera at Yorghan Tepe (Nuzi), and the British archaeologist

Max Mallowan at Chagar Bazar and Tell Brak. Recent excavations and

surveys in progress are conducted by American, Belgian, Danish,

Dutch, French, German and Italian teams of archaeologists, with

international participants, in cooperation with the Syrian Department

of Antiquities. The tells, or city mounds, often reveal a long occupation

beginning in the Neolithic and ending in the Roman period or later.

The characteristic Hurrian pottery, the Khabur ware, is helpful

in determining the different strata of occupation within the mounds.

The Hurrian settlements are usually identified from the Middle Bronze

Age to the end of the Late Bronze Age, with Tell Mozan (Urkesh)

being the main exception.

Important

sites :

The list includes some important ancient sites from the area dominated

by the Hurrians. Excavation reports and images are found at the

websites linked. As noted above, important discoveries of Hurrian

culture and history were also made at Alalakh, Amarna, Hattusa and

Ugarit.

•

Tell Mozan (ancient

Urkesh)

• Yorghan

Tepe (ancient Nuzi)

• Tell

Brak (ancient Nagar)

• Tell

Leilan (ancient Shehna and Shubat-Enlil)

• Tell

Barri (ancient Kahat)

• Tell

Beydar (ancient Nabada)

• Kenan

Tepe

• Tell

Tuneinir

• Umm

el-Marra (ancient Tuba?)

• Tell

Chuera

• Hammam

al Turkman (ancient Zalpa?)

• Tell

Sabi Abyad

• Hamoukar

• Chagar

Bazar

• Tell

el Fakhariya / Ras el Ayn (ancient Washukanni?)

• Tell

Hamidiya (ancient Taidu?)

Source

:

https://en.wikipedia.org/

wiki/Hurrians