| CLASSICAL ANTIQUITY

The Parthenon is one of the most recognizable symbols of the classical era, exemplifying ancient Greek culture Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 6th century AD centered on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ancient Greece and ancient Rome known as the Greco-Roman world. It is the period in which both Greek and Roman societies flourished and wielded great influence throughout much of Europe, Northern Africa, and West Asia.

Conventionally, it is taken to begin with the earliest-recorded Epic Greek poetry of Homer (8th–7th-century BC), and continues through the emergence of Christianity and the fall of the Western Roman Empire (5th-century AD). It ends with the decline of classical culture during Late antiquity (250–750), a period overlapping with the Early Middle Ages (600–1000). Such a wide span of history and territory covers many disparate cultures and periods. Classical antiquity may also refer to an idealized vision among later people of what was, in Edgar Allan Poe's words, "the glory that was Greece, and the grandeur that was Rome".

The culture of the ancient Greeks, together with some influences from the ancient Near East, was the basis of art, philosophy, society, and education, until the Roman imperial period. The Romans preserved, imitated, and spread this culture over Europe, until they themselves were able to compete with it, and the classical world began to speak Latin as well as Greek. This Greco-Roman cultural foundation has been immensely influential on the language, politics, law, educational systems, philosophy, science, warfare, poetry, historiography, ethics, rhetoric, art and architecture of the modern world. Surviving fragments of classical culture led to a revival beginning in the 14th century which later came to be known as the Renaissance, and various neo-classical revivals occurred in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Archaic

period (c. 8th to c. 6th centuries BC) :

Phoenicians, Carthaginians and Assyrians :

The Phoenicians originally expanded from Canaan ports, by the 8th century dominating trade in the Mediterranean. Carthage was founded in 814 BC, and the Carthaginians by 700 BC had firmly established strongholds in Sicily, Italy and Sardinia, which created conflicts of interest with Etruria. A stela found in Kition, Cyprus commemorates the victory of King Sargon II in 709 BC over the seven kings of the island, marking an important step in the transfer of Cyprus from Tyrian rule to the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

Greece

:

In pottery, the Archaic period sees the development of the Orientalizing style, which signals a shift from the Geometric style of the later Dark Ages and the accumulation of influences derived from Egypt, Phoenicia and Syria.

Pottery styles associated with the later part of the Archaic age are the black-figure pottery, which originated in Corinth during the 7th-century BC and its successor, the red-figure style, developed by the Andokides Painter in about 530 BC.

Greek

colonies :

Etruscan civilization in north of Italy, 800 BC The Etruscans had established political control in the region by the late 7th-century BC, forming the aristocratic and monarchial elite. The Etruscans apparently lost power in the area by the late 6th-century BC, and at this point, the Italic tribes reinvented their government by creating a republic, with much greater restraints on the ability of rulers to exercise power.

Roman

Kingdom :

Archaeological evidence indeed shows first traces of settlement at the Roman Forum in the mid-8th BC, though settlements on the Palatine Hill may date back to the 10th century BC.

The seventh and final king of Rome was Tarquinius Superbus. As the son of Tarquinius Priscus and the son-in-law of Servius Tullius, Superbus was of Etruscan birth. It was during his reign that the Etruscans reached their apex of power. Superbus removed and destroyed all the Sabine shrines and altars from the Tarpeian Rock, enraging the people of Rome. The people came to object to his rule when he failed to recognize the rape of Lucretia, a patrician Roman, at the hands of his own son. Lucretia's kinsman, Lucius Junius Brutus (ancestor to Marcus Brutus), summoned the Senate and had Superbus and the monarchy expelled from Rome in 510 BC. After Superbus' expulsion, the Senate voted to never again allow the rule of a king and reformed Rome into a republican government is 509 BC. In fact, the Latin word "Rex" meaning King became a dirty and hated word throughout the Republic and later on the Empire.[citation needed]

Classical Greece (5th to 4th centuries BC) :

Delian League ("Athenian Empire"), right before the Peloponnesian War in 431 BC The classical period of Ancient Greece corresponds to most of the 5th and 4th centuries BC, in particular, from the fall of the Athenian tyranny in 510 BC to the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC. In 510, Spartan troops helped the Athenians overthrow the tyrant Hippias, son of Peisistratos. Cleomenes I, king of Sparta, put in place a pro-Spartan oligarchy conducted by Isagoras.

The Greco-Persian Wars (499–449 BC), concluded by the Peace of Callias gave way not only to the liberation of Greece, Macedon, Thrace, and Ionia from Persian rule, but also resulted in giving the dominant position of Athens in the Delian League, which led to conflict with Sparta and the Peloponnesian League, resulting in the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), which ended in a Spartan victory.

Greece entered the 4th century under Spartan hegemony, but by 395 BC the Spartan rulers removed Lysander from office, and Sparta lost her naval supremacy. Athens, Argos, Thebes and Corinth, the latter two of which were formerly Spartan allies, challenged Spartan dominance in the Corinthian War, which ended inconclusively in 387 BC. Later, in 371 BC, the Theban generals Epaminondas and Pelopidas won a victory at the Battle of Leuctra. The result of this battle was the end of Spartan supremacy and the establishment of Theban hegemony. Thebes sought to maintain its position until it was finally eclipsed by the rising power of Macedon in 346 BC.

Under Philip II, (359–336 BC), Macedon expanded into the territory of the Paeonians, the Thracians and the Illyrians. Philip's son, Alexander the Great, (356–323 BC) managed to briefly extend Macedonian power not only over the central Greek city-states but also to the Persian Empire, including Egypt and lands as far east as the fringes of India. The classical period conventionally ends at the death of Alexander in 323 BC and the fragmentation of his empire, which was at this time divided among the Diadochi.

Hellenistic

period (323–146 BC) :

The Hellenistic period ended with the rise of the Roman Republic to a super-regional power in the 2nd century BC and the Roman conquest of Greece in 146 BC.

Roman Republic (5th to 1st centuries BC) :

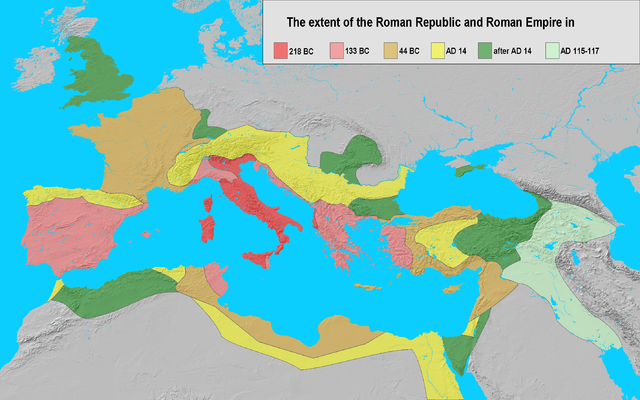

The

extent of the Roman Republic and Roman Empire in 218 BC (dark red),

133 BC (light red), 44 BC (orange), 14 AD (yellow), after 14 AD

(green), and maximum extension under Trajan 117 (light green).

Roman Empire (1st century BC to 5th century AD) :

The precise end of the Republic is disputed by modern historians; Roman citizens of the time did not recognize that the Republic had ceased to exist. The early Julio-Claudian Emperors maintained that the res publica still existed, albeit under the protection of their extraordinary powers, and would eventually return to its full Republican form. The Roman state continued to call itself a res publica as long as it continued to use Latin as its official language.

Rome acquired imperial character de facto from the 130s BC with the acquisition of Cisalpine Gaul, Illyria, Greece and Hispania, and definitely with the addition of Iudaea, Asia Minor and Gaul in the 1st century BC. At the time of the empire's maximal extension under Trajan (AD 117), Rome controlled the entire Mediterranean as well as Gaul, parts of Germania and Britannia, the Balkans, Dacia, Asia Minor, the Caucasus, and Mesopotamia.

Culturally, the Roman Empire was significantly Hellenized, but also saw the rise of syncretic "eastern" traditions, such as Mithraism, Gnosticism, and most notably Christianity. The empire began to decline in the crisis of the third century.

While sometimes compared with classical Greece, [by whom?] classical Rome had vast differences within their family life. Fathers had great power over their children, and husbands over their wives, and these acts were commonly compared with slave-owners and slaves. In fact, the word family, familia in Latin, actually referred to those who were under the authority of a male head of household. This included non-related members such as slaves and servants. In marriage, both men and women were loyal to one another and shared property. Divorce was first allowed starting in the first century BC and could be done by either man or woman.

Late antiquity (4th to 6th centuries AD) :

The Western and Eastern Roman Empires by 476 Late antiquity saw the rise of Christianity under Constantine I, finally ousting the Roman imperial cult with the Theodosian decrees of 393. Successive invasions of Germanic tribes finalized the decline of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, while the Eastern Roman Empire persisted throughout the Middle Ages, in a state called the Roman Empire by its citizens, and labeled the Byzantine Empire by later historians. Hellenistic philosophy was succeeded by continued developments in Platonism and Epicureanism, with Neoplatonism in due course influencing the theology of the Church Fathers.

Many writers have attempted to put a specific date on the symbolic "end" of antiquity with the most prominent dates being the deposing of the last Western Roman Emperor in 476, the closing of the last Platonic Academy in Athens by the Eastern Roman Emperor Justinian I in 529, and the conquest of much of the Mediterranean by the new Muslim faith from 634–718. These Muslim conquests, of Syria (637), Egypt (639), Cyprus (654), North Africa (665), Hispania (718), Southern Gaul (720), Crete (820), and Sicily (827), Malta (870) (and the sieges of the Eastern Roman capital, First Arab Siege of Constantinople (674–78) and Second Arab Siege of Constantinople (717–18)) severed the economic, cultural, and political links that had traditionally united the classical cultures around the Mediterranean, ending antiquity.

The Byzantine Empire in 650 after the Arabs conquered the provinces of Syria and Egypt. At the same time early Slavs settled in the Balkans The original Roman Senate continued to express decrees into the late 6th century, and the last Eastern Roman emperor to use Latin as the language of his court in Constantinople was emperor Maurice, who reigned until 602. The overthrow of Maurice by his mutinying Danube army under Phocas resulted in the Slavic invasion of the Balkans and the decline of Balkan and Greek urban culture (leading to the flight of Balkan Latin speakers to the mountains, see Origin of the Romanians), and also provoked the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628 in which all the great eastern cities except Constantinople were lost. The resulting turmoil did not end until the Muslim conquests of the 7th century finalized the irreversible loss of all the largest Eastern Roman imperial cities besides the capital itself. The emperor Heraclius in Constantinople, who emerged during this period, conducted his court in Greek, not Latin, though Greek had always been an administrative language of the eastern Roman regions. Eastern-Western links weakened with the ending of the Byzantine Papacy.

The Eastern Roman empire's capital city of Constantinople was left as the only unconquered large urban center of the original Roman empire, as well as being the largest city in Europe. Over the next millennium the Roman culture of that city would slowly change, leading modern historians to refer to it by a new name, Byzantine, though many classical books, sculptures, and technologies survived there along with classical Roman cuisine and scholarly traditions, well into the Middle Ages, when much of it was "rediscovered" by visiting Western crusaders. Indeed, the inhabitants of Constantinople continued to refer to themselves as Romans, as did their eventual conquerors in 1453, the Ottomans. (see Rûm and Romaioi.) The classical scholarship and culture that was still preserved in Constantinople were brought by refugees fleeing its conquest in 1453 and helped to spark the Renaissance (see Greek scholars in the Renaissance).

Ultimately, it was a slow, complex, and graduated change in the socio-economic structure in European history that led to the changeover between Classical antiquity and Medieval society and no specific date can truly exemplify that.

Political

revivalism :

That model continued to exist in Constantinople for the entirety of the Middle Ages; the Byzantine Emperor was considered the sovereign of the entire Christian world. The Patriarch of Constantinople was the Empire's highest-ranked cleric, but even he was subordinate to the Emperor, who was "God's Vicegerent on Earth". The Greek-speaking Byzantines and their descendants continued to call themselves "Romans" until the creation of a new Greek state in 1832.

After the fall of Constantinople in 1453, the Russian Czars (a title derived from Caesar) claimed the Byzantine mantle as the champion of Orthodoxy; Moscow was described as the "Third Rome" and the Czars ruled as divinely-appointed Emperors into the 20th century.

Despite the fact that the Western Roman secular authority disappeared entirely in Europe, it still left traces. The Papacy and the Catholic Church in particular maintained Latin language, culture, and literacy for centuries; to this day the popes are called Pontifex Maximus which in the classical period was a title belonging to the Emperor, and the ideal of Christendom carried on the legacy of a united European civilization even after its political unity had disappeared.

The political idea of an Emperor in the West to match the Emperor in the East continued after the Western Roman Empire's collapse; it was revived by the coronation of Charlemagne in 800; the self-described Holy Roman Empire ruled over central Europe until 1806.

The Renaissance idea that the classical Roman virtues had been lost under medievalism was especially powerful in European politics of the 18th and 19th centuries. Reverence for Roman republicanism was strong among the Founding Fathers of the United States and the Latin American revolutionaries; the Americans described their new government as a republic (from res publica) and gave it a Senate and a President (another Latin term), rather than make use of available English terms like commonwealth or parliament.

Similarly in Revolutionary and Napoleonic France, republicanism and Roman martial virtues were upheld by the state, as can be seen in the architecture of the Panthéon, the Arc de Triomphe, and the paintings of Jacques-Louis David. During the revolution, France itself followed the transition from kingdom to republic to dictatorship to Empire (complete with Imperial Eagles) that Rome had undergone centuries earlier.

Cultural legacy :

Plato and Aristotle walking and disputing. Detail from Raphael's The School of Athens (1509 – 1511) Classical antiquity is a broad term for a long period of cultural history. Such a wide sampling of history and territory covers many rather disparate cultures and periods. "Classical antiquity" often refers to an idealized vision of later people, of what was, in Edgar Allan Poe's words, the glory that was Greece, the grandeur that was Rome!

In the 18th and 19th centuries AD, reverence for classical antiquity was much greater in Europe and the United States than it is today. Respect for the ancient people of Greece and Rome affected politics, philosophy, sculpture, literature, theatre, education, architecture, and sexuality.

Epic poetry in Latin continued to be written and circulated well into the 19th century. John Milton and even Arthur Rimbaud received their first poetic educations in Latin. Genres like epic poetry, pastoral verse, and the endless use of characters and themes from Greek mythology left a deep mark on Western literature. In architecture, there have been several Greek Revivals, which seem more inspired in retrospect by Roman architecture than Greek. Washington, DC is filled with large marble buildings with facades made out to look like Greek temples, with columns constructed in the classical orders of architecture.

In philosophy, the efforts of St Thomas Aquinas were derived largely from the thought of Aristotle, despite the intervening change in religion from Hellenic Polytheism to Christianity. [citation needed] Greek and Roman authorities such as Hippocrates and Galen formed the foundation of the practice of medicine even longer than Greek thought prevailed in philosophy. In the French theater, tragedians such as Molière and Racine wrote plays on mythological or classical historical subjects and subjected them to the strict rules of the classical unities derived from Aristotle's Poetics. The desire to dance like a latter-day vision of how the ancient Greeks did it moved Isadora Duncan to create her brand of ballet.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |