| DACIANS

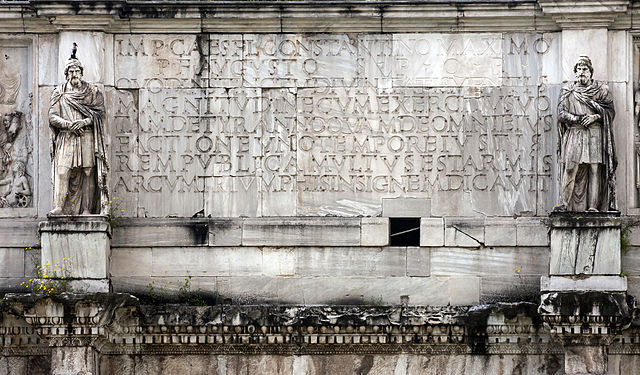

Two of the eight marble statues of Dacian warriors surmounting the Arch of Constantine in Rome The Dacians were a Thracian people who were the ancient inhabitants of the cultural region of Dacia, located in the area near the Carpathian Mountains and west of the Black Sea. This area includes mainly the present-day countries of Romania and Moldova, as well as parts of Ukraine, Eastern Serbia, Northern Bulgaria, Slovakia, Hungary and Southern Poland. The Dacians spoke the Dacian language, a sub-group of Thracian, but were somewhat culturally influenced by the neighbouring Scythians and by the Celtic invaders of the 4th century BC.[citation needed]

Name

and etymology :

By contrast, the name of Dacians, whatever the origin of the name, was used by the more western tribes who adjoined the Pannonians and therefore first became known to the Romans. According to Strabo's Geographica, the original name of the Dacians was "Daoi". The name Daoi (one of the ancient Geto-Dacian tribes) was certainly adopted by foreign observers to designate all the inhabitants of the countries north of Danube that had not yet been conquered by Greece or Rome.

The ethnographic name Daci is found under various forms within ancient sources. Greeks used the forms "Dakoi" (Strabo, Dio Cassius, and Dioscorides) and "Daoi" (singular Daos). The form "Daoi" was frequently used according to Stephan of Byzantium.

Latins used the forms Davus, Dacus, and a derived form Dacisci (Vopiscus and inscriptions).

There are similarities between the ethnonyms of the Dacians and those of Dahae (Greek Dáoi, Dáai, Dai, Dasai; Latin Dahae, Daci), an Indo-European people located east of the Caspian Sea, until the 1st millennium BC. Scholars have suggested that there were links between the two peoples since ancient times. The historian David Gordon White has, moreover, stated that the "Dacians ... appear to be related to the Dahae". (Likewise White and other scholars also believe that the names Dacii and Dahae may also have a shared etymology)

By the end of the first century AD, all the inhabitants of the lands which now form Romania were known to the Romans as Daci, with the exception of some Celtic and Germanic tribes who infiltrated from the west, and Sarmatian and related people from the east.

Etymology

:

One hypothesis is that the name Getae originates in the Indo-European *guet- 'to utter, to talk'. Another hypothesis is that "Getae" and "Daci" are Iranian names of two Iranian-speaking Scythian groups that had been assimilated into the larger Thracian-speaking population of the later "Dacia". They might be related to Masagetae and Dahae people who used to live in central Asia in 6th century BC.[citation needed]

Early

history of etymological approaches :

Modern

theories :

•

A possible connection

with the Phrygians was proposed by Dimitar Dechev (in a work not

published until 1957). [citation needed] The Phrygian language word

daos meant "wolf", [citation needed] and Daos was also

a Phrygian deity. In later times, Roman auxiliaries recruited from

the Dacian area were also known as Phrygi. [citation needed] Such

a connection was supported by material from Hesychius of Alexandria

(5th/6th century), as well as the 20th century historian Mircea

Eliade.

Another etymology, linked to the Proto-Indo-European language roots *dhe- meaning "to set, place" and dheua → dava ("settlement") and dhe-k → daci is supported by Romanian historian Ioan I. Russu (1967).

Mythological theories :

Dacian Draco as from Trajan's Column Mircea Eliade attempted, in his book From Zalmoxis to Genghis Khan, to give a mythological foundation to an alleged special relation between Dacians and the wolves :

•

Dacians might

have called themselves "wolves" or "ones the same

with wolves", suggesting religious significance.

Indo-Europeanization was complete by the beginning of the Bronze Age. The people of that time are best described as proto-Thracians, which later developed in the Iron Age into Danubian-Carpathian Geto-Dacians as well as Thracians of the eastern Balkan Peninsula.

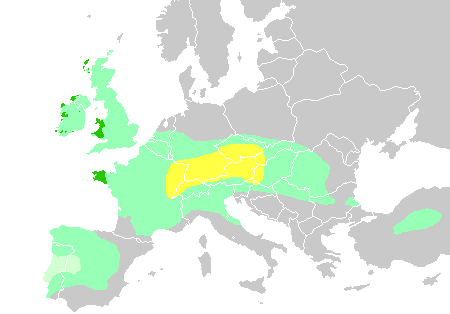

Between BC 15th–12th century, the Dacian-Getae culture was influenced by the Bronze Age Tumulus-Urnfield warriors who were on their way through the Balkans to Anatolia. When the La Tène Celts arrived in BC 4th century, the Dacians were under the influence of the Scythians.

Alexander the Great attacked the Getae in BC 335 on the lower Danube, but by BC 300 they had formed a state founded on a military democracy, and began a period of conquest. More Celts arrived during the BC 3rd century, and in BC 1st century the people of Boii tried to conquer some of the Dacian territory on the eastern side of the Teiss river. The Dacians drove the Boii south across the Danube and out of their territory, at which point the Boii abandoned any further plans for invasion.

Identity

and distribution :

Linguistic

affiliation :

The Dacians are generally considered [by whom?] to have been Thracian speakers, representing a cultural continuity [specify] from earlier Iron Age communities loosely termed [by whom?] Getic. Since in one interpretation, Dacian is a variety of Thracian, for the reasons of convenience, the generic term ‘Daco-Thracian" is used, with "Dacian" reserved for the language or dialect that was spoken north of Danube, in present-day Romania and eastern Hungary, and "Thracian" for the variety spoken south of the Danube. There is no doubt that the Thracian language was related to the Dacian language which was spoken in what is today Romania, before some of that area was occupied by the Romans. Also, both Thracian and Dacian have one of the main satem characteristic changes of Indo-European language, *k and *g to *s and *z. With regard to the term "Getic" (Getae), even though attempts have been made to distinguish between Dacian and Getic, there seems no compelling reason to disregard the view of the Greek geographer Strabo that the Daci and the Getae, Thracian tribes dwelling north of the Danube (the Daci in the west of the area and the Getae further east), were one and the same people and spoke the same language.

Another variety that has sometimes been recognized [by whom?] is that of Moesian (or Mysian) for the language of an intermediate area immediately to the south of Danube in Serbia, Bulgaria and Romanian Dobruja: this and the dialects north of the Danube have been grouped together as Daco-Moesian. The language of the indigenous population has left hardly any trace in the anthroponymy of Moesia, but the toponymy indicates that the Moesii on the south bank of the Danube, north of the Haemus Mountains, and the Triballi in the valley of the Morava, shared a number of characteristic linguistic features [specify] with the Dacii south of the Carpathians and the Getae in the Wallachian plain, which sets them apart from the Thracians though their languages are undoubtedly related.

Dacian culture is mostly followed through Roman sources. Ample evidence suggests that they were a regional power in and around the city of Sarmizegetusa. Sarmizegetusa was their political and spiritual capital. The ruined city lies high in the mountains of central Romania.

Vladimir Georgiev disputes that Dacian and Thracian were closely related for various reasons, most notably that Dacian and Moesian town names commonly end with the suffix -DAVA, while towns in Thrace proper (i.e. South of the Balkan mountains) generally end in -PARA (see Dacian language). According to Georgiev, the language spoken by the ethnic Dacians should be classified as "Daco-Moesian" and regarded as distinct from Thracian. Georgiev also claimed that names from approximately Roman Dacia and Moesia show different and generally less extensive changes in Indo-European consonants and vowels than those found in Thrace itself. However, the evidence seems to indicate divergence of a Thraco-Dacian language into northern and southern groups of dialects, not so different as to qualify as separate languages. Polomé considers that such lexical differentiation ( -dava vs. para) would, however, be hardly enough evidence to separate Daco-Moesian from Thracian.

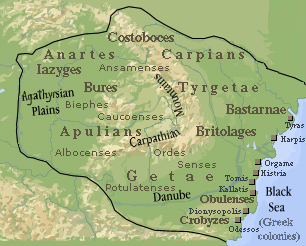

Tribes :

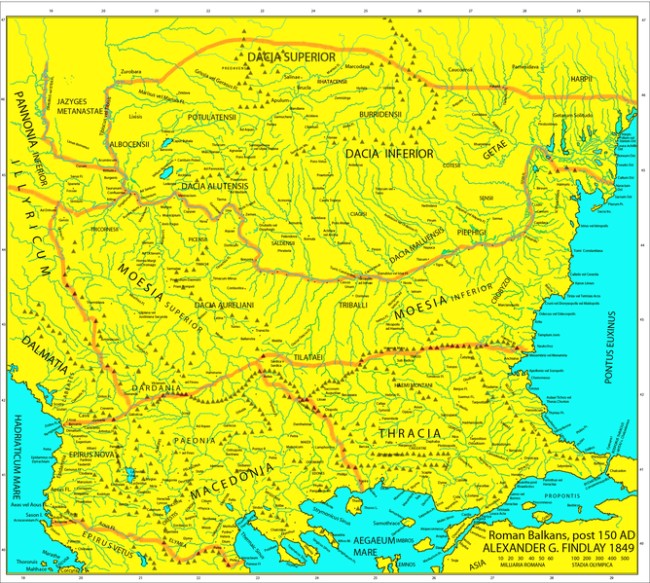

An extensive account of the native tribes in Dacia can be found in the ninth tabula of Europe of Ptolemy's Geography. The Geography was probably written in the period AD 140–150, but the sources were often earlier; for example, Roman Britain is shown before the building of Hadrian's Wall in the AD 120s. Ptolemy's Geography also contains a physical map probably designed before the Roman conquest, and containing no detailed nomenclature. There are references to the Tabula Peutingeriana, but it appears that the Dacian map of the Tabula was completed after the final triumph of Roman nationality. Ptolemy's list includes no fewer than twelve tribes with Geto-Dacian names.

The fifteen tribes of Dacia as named by Ptolemy, starting from the northernmost ones, are as follows. First, the Anartes, the Teurisci and the Coertoboci/Costoboci. To the south of them are the Buredeense (Buri/Burs), the Cotense/Cotini and then the Albocense, the Potulatense and the Sense, while the southernmost were the Saldense, the Ciaginsi and the Piephigi. To the south of them were Predasense/Predavenses, the Rhadacense/Rhatacenses, the Caucoense (Cauci) and Biephi. Twelve out of these fifteen tribes listed by Ptolemy are ethnic Dacians, and three are Celt Anarti, Teurisci, and Cotense. There are also previous brief mentions of other Getae or Dacian tribes on the left and right banks of the Danube, or even in Transylvania, to be added to the list of Ptolemy. Among these other tribes are the Trixae, Crobidae and Appuli.

Some peoples inhabiting the region generally described in Roman times as "Dacia" were not ethnic Dacians.The true Dacians were a people of Thracian descent. German elements (Daco-Germans), Celtic elements (Daco-Celtic) and Iranian elements (Daco-Sarmatian) occupied territories in the north-west and north-east of Dacia. This region covered roughly the same area as modern Romania plus Bessarabia (Republic of Moldova) and eastern Galicia (south-west Ukraine), although Ptolemy places Moldavia and Bessarabia in Sarmatia Europaea, rather than Dacia. After the Dacian Wars (AD 101-6), the Romans occupied only about half of the wider Dacian region. The Roman province of Dacia covered just western Wallachia as far as the Limes Transalutanus (East of the river Aluta, or Olt) and Transylvania, as bordered by the Carpathians.

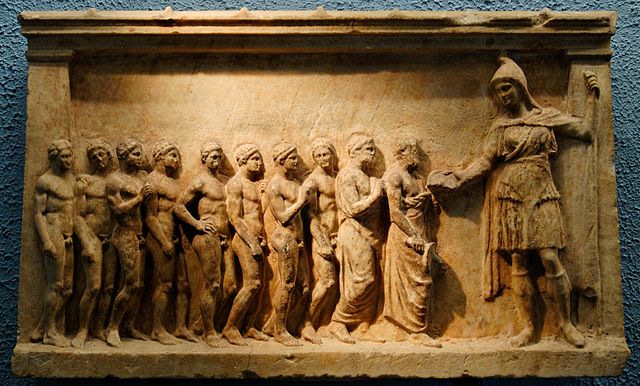

The impact of the Roman conquest on these people is uncertain. One hypothesis was that they were effectively eliminated. An important clue to the character of Dacian casualties is offered by the ancient sources Eutropius and Crito. Both speak about men when they describe the losses suffered by the Dacians in the wars. This suggests that both refer to losses due to fighting, not due to a process of extermination of the whole population. A strong component of the Dacian army, including the Celtic Bastarnae and the Germans, had withdrawn rather than submit to Trajan. Some scenes on Trajan's Column represent acts of obedience of the Dacian population, and others show the refugee Dacians returning to their own places. Dacians trying to buy amnesty are depicted on Trajan's Column (one offers to Trajan a tray of three gold ingots).

Alternatively, a substantial number may have survived in the province, although were probably outnumbered by the Romanised immigrants. Cultural life in Dacia became very mixed and decidedly cosmopolitan because of the colonial communities. The Dacians retained their names and their own ways in the midst of the newcomers, and the region continued to exhibit Dacian characteristics. The Dacians who survived the war are attested as revolting against the Roman domination in Dacia at least twice, in the period of time right after the Dacian Wars, and in a more determined manner in 117 AD. In 158 AD, they revolted again, and were put down by M. Statius Priscus. Some Dacians were apparently expelled from the occupied zone at the end of each of the two Dacian Wars or otherwise emigrated. It is uncertain where these refugees settled. Some of these people might have mingled with the existing ethnic Dacian tribes beyond the Carpathians (the Costoboci and Carpi).

After Trajan's conquest of Dacia, there was recurring trouble involving Dacian groups excluded from the Roman province, as finally defined by Hadrian. By the early third century the "Free Dacians", as they were earlier known, were a significantly troublesome group, then identified as the Carpi, requiring imperial intervention on more than one occasion. In 214 Caracalla dealt with their attacks. Later, Philip the Arab came in person to deal with them; he assumed the triumphal title Carpicus Maximus and inaugurated a new era for the province of Dacia (July 20, 246). Later both Decius and Gallienus assumed the titles Dacicus Maximus. In 272, Aurelian assumed the same title as Philip.

In about 140 AD, Ptolemy lists the names of several tribes residing on the fringes of the Roman Dacia (west, east and north of the Carpathian range), and the ethnic picture seems to be a mixed one. North of the Carpathians are recorded the Anarti, Teurisci and Costoboci. The Anarti (or Anartes) and the Teurisci were originally probably Celtic peoples or mixed Dacian-Celtic. The Anarti, together with the Celtic Cotini, are described by Tacitus as vassals of the powerful Quadi Germanic people. The Teurisci were probably a group of Celtic Taurisci from the eastern Alps. However, archaeology has revealed that the Celtic tribes had originally spread from west to east as far as Transylvania, before being absorbed by the Dacians in the 1st century BC.

Costoboci

:

Based on the account of Dio Cassius, Heather (2010) considers that Hasding Vandals, around 171 AD, attempted to take control of lands which previously belonged to the free Dacian group called the Costoboci. Hrushevskyi (1997) mentions that the earlier widespread view that these Carpathian tribes were Slavic has no basis. This would be contradicted by the Coestobocan names themselves that are known from the inscriptions, written by a Coestobocan and therefore presumably accurately. These names sound quite unlike anything Slavic. Scholars such as Tomaschek (1883), Shutte (1917) and Russu (1969) consider these Costobocian names to be Thraco-Dacian. This inscription also indicates the Dacian background of the wife of the Costobocian king "Ziais Tiati filia Daca". This indication of the socio-familial line of descent seen also in other inscriptions (i.e. Diurpaneus qui Euprepes Sterissae f(ilius) Dacus) is a custom attested since the historical period (beginning in the 5th century BC) when Thracians were under Greek influence. It may not have originated with the Thracians, as it could be just a fashion borrowed from Greeks for specifying ancestry and for distinguishing homonymous individuals within the tribe.Shutte (1917), Parvan, and Florescu (1982) pointed also to the Dacian characteristic place names ending in '–dava' given by Ptolemy in the Costoboci's country.

Carpi

:

The ancient sources about the Carpi, before 104 AD, located them on a territory situated between the western side of Eastern European Galicia and the mouth of the Danube. The name of the tribe is homonymous with the Carpathian mountains. Carpi and Carpathian are Dacian words derived from the root (s)ker- "cut" cf. Albanian karp "stone" and Sanskrit kar- "cut". A quote from the 6th-century Byzantine chronicler Zosimus referring to the Carpo-Dacians (Latin: Carpo-Dacae), who attacked the Romans in the late 4th century, is seen as evidence of their Dacian ethnicity. In fact, Carpi/Carpodaces is the term used for Dacians outside of Dacia proper.However, that the Carpi were Dacians is shown not so much by the form in Zosimus as by their characteristic place-names in –dava, given by Ptolemy in their country. The origin and ethnic affiliations of the Carpi have been debated over the years; in modern times they are closely associated with the Carpathian Mountains, and a good case has been made for attributing to the Carpi a distinct material culture, "a developed form of the Geto-Dacian La Tene culture", often known as the Poienesti culture, which is characteristic of this area.

Physical characteristics :

Roman monument commemorating the Battle of Adamclisi clearly shows two giant Dacian warriors wielding a two-handed falx Dacians are represented in the statues surmounting the Arch of Constantine and on Trajan's Column. The artist of the Column took some care to depict, in his opinion, a variety of Dacian people—from high-ranking men, women, and children to the near-savage. Although the artist looked to models in Hellenistic art for some body types and compositions, he does not represent the Dacians as generic barbarians.

Classical authors applied a generalized stereotype when describing the "barbarians"—Celts, Scythians, Thracians—inhabiting the regions to the north of the Greek world. In accordance with this stereotype, all these peoples are described, in sharp contrast to the "civilized" Greeks, as being much taller, their skin lighter and with straight light-coloured hair and blue eyes. For instance, Aristotle wrote that "the Scythians on the Black Sea and the Thracians are straight-haired, for both they themselves and the environing air are moist"; according to Clement of Alexandria, Xenophanes described the Thracians as "ruddy and tawny". On Trajan's column, Dacian soldiers' hair is depicted longer than the hair of Roman soldiers and they had trimmed beards.

Body-painting was customary among the Dacians. [specify] It is probable that the tattooing originally had a religious significance. They practiced symbolic-ritual tattooing or body painting for both men and women, with hereditary symbols transmitted up to the fourth generation.

History

:

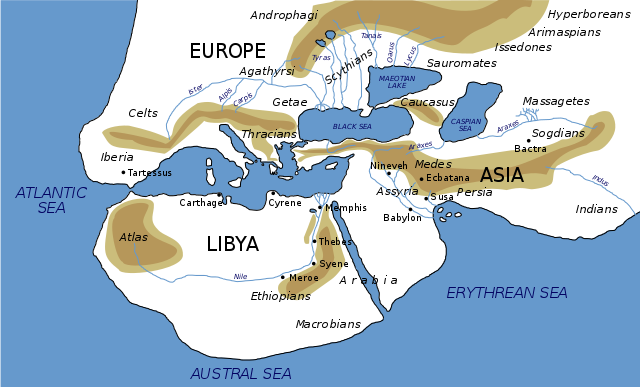

Getae on the World Map according to Herodotus In the absence of historical records written by the Dacians (and Thracians) themselves, analysis of their origins depends largely on the remains of material culture. On the whole, the Bronze Age witnessed the evolution of the ethnic groups which emerged during the Eneolithic period, and eventually the syncretism of both autochthonous and Indo-European elements from the steppes and the Pontic regions. Various groups of Thracians had not separated out by 1200 BC, but there are strong similarities between the ceramic types found at Troy and the ceramic types from the Carpathian area. About the year 1000 BC, the Carpatho-Danubian countries were inhabited by a northern branch of the Thracians. At the time of the arrival of the Scythians (c. 700 BC), the Carpatho-Danubian Thracians were developing rapidly towards the Iron Age civilization of the West. Moreover, the whole of the fourth period of the Carpathian Bronze Age had already been profoundly influenced by the first Iron Age as it developed in Italy and the Alpine lands. The Scythians, arriving with their own type of Iron Age civilization, put a stop to these relations with the West. From roughly 500 BC (the second Iron Age), the Dacians developed a distinct civilization, which was capable of supporting large centralised kingdoms by 1st BC and 1st AD.

Since the very first detailed account by Herodotus, Getae are acknowledged as belonging to the Thracians.Still, they are distinguished from the other Thracians by particularities of religion and custom. The first written mention of the name "Dacians" is in Roman sources, but classical authors are unanimous in considering them a branch of the Getae, a Thracian people known from Greek writings. Strabo specified that the Daci are the Getae who lived in the area towards the Pannonian plain (Transylvania), while the Getae proper gravitated towards the Black Sea coast (Scythia Minor).

Relations

with Thracians :

In the 19th century, Tomaschek considered a close affinity between the Besso-Thracians and Getae-Dacians, an original kinship of both people with Iranian peoples. They are Aryan tribes, several centuries before Scolotes of the Pont and Sauromatae left the Aryan homeland and settled in the Carpathian chain, in the Haemus (Balkan) and Rhodope mountains. The Besso-Thracians and Getae-Dacians separated very early from Aryans, since their language still maintains roots that are missing from Iranian and it shows non-Iranian phonetic characteristics (i.e. replacing the Iranian "l" with "r"). He considered that the Geto-Dacians and Besso-Thracians would represent a new layer of people that extended in the autochthonous fund, probably Illyrian or Armenian-Phrygian.

Relations with Celts :

Geto-Dacians inhabited both sides of the Tisa River before the rise of the Celtic Boii, and again after the latter were defeated by the Dacians under king Burebista. During the second half of the 4th century BC, Celtic cultural influence appears in the archaeological records of the middle Danube, Alpine region, and north-western Balkans, where it was part of the Middle La Tène material culture. This material appears in north-western and central Dacia, and is reflected especially in burials. The Dacians absorbed the Celtic influence from the northwest in the early third century BC. Archaeological investigation of this period has highlighted several Celtic warrior graves with military equipment. It suggests the forceful penetration of a military Celtic elite within the region of Dacia, now known as Transylvania, that is bounded on the east by the Carpathian range. The archaeological sites of the third and second centuries BC in Transylvania revealed a pattern of co-existence and fusion between the bearers of La Tène culture and indigenous Dacians. These were domestic dwellings with a mixture of Celtic and Dacian pottery, and several graves in the Celtic style containing vessels of Dacian type. There are some seventy Celtic sites in Transylvania, mostly cemeteries, but most if not all of them indicate that the native population imitated Celtic art forms that took their fancy, but remained obstinately and fundamentally Dacian in their culture.

Replica of the raven-totem helmet from Satu Mare County The Celtic Helmet from Satu Mare, Romania (northern Dacia), an Iron Age raven totem helmet, dated around the 4th century BC. A similar helmet is depicted on the Thraco-Celtic Gundestrup cauldron, being worn by one of the mounted warriors (detail tagged here). See also an illustration of Brennos wearing a similar helmet. Around 150 BC, La Tène material disappears from the area. This coincides with the ancient writings which mention the rise of Dacian authority. It ended the Celtic domination, and it is possible that Celts were driven out of Dacia. Alternatively, some scholars have proposed that the Transylvanian Celts remained, but merged into the local culture and thus ceased to be distinctive.

Archaeological discoveries in the settlements and fortifications of the Dacians in the period of their kingdoms (1st century BC and 1st century AD) included imported Celtic vessels and others made by Dacian potters imitating Celtic prototypes, showing that relations between the Dacians and the Celts from the regions north and west of Dacia continued. In present-day Slovakia, archaeology has revealed evidence for mixed Celtic-Dacian populations in the Nitra and Hron river basins.

After the Dacians subdued the Celtic tribes, the remaining Cotini stayed in the mountains of Central Slovakia, where they took up mining and metalworking. Together with the original domestic population, they created the Puchov culture that spread into central and northern Slovakia, including Spis, and penetrated northeastern Moravia and southern Poland. Along the Bodrog River in Zemplin they created Celtic-Dacian settlements which were known for the production of painted ceramics.

Relations

with Greeks :

Relations

with Persians :

Relations with Scythians :

Agathyrsi

Transylvania :

The opinion that the Agathyrsi were almost certainly Thracians results also from the writings preserved by Stephen of Byzantium, who explains that the Greeks called the Trausi the Agathyrsi, and we know that the Trausi lived in the Rhodope Mountains. Certain details from their way of life, such as tattooing, also suggest that the Agathyrsi were Thracians. Their place was later taken by the Dacians. That the Dacians were of Thracian stock is not in doubt, and it is safe to assume that this new name also encompassed the Agathyrsi, and perhaps other neighbouring Thracian people as well, as a result of some political upheaval.

Relations with Germanic tribes :

The Goths, a confederation of east German peoples, arrived in the southern Ukraine no later than 230.During the next decade, a large section of them moved down the Black Sea coast and occupied much of the territory north of the lower Danube. The Goths' advance towards the area north of the Black Sea involved competing with the indigenous population of Dacian-speaking Carpi, as well as indigenous Iranian-speaking Sarmatians and Roman garrison forces. The Carpi, often called "Free Dacians", continued to dominate the anti-Roman coalition made up of themselves, Taifali, Astringi, Vandals, Peucini, and Goths until 248, when the Goths assumed the hegemony of the loose coalition. The first lands taken over by the Thervingi Goths were in Moldavia, and only during the fourth century did they move in strength down into the Danubian plain. The Carpi found themselves squeezed between the advancing Goths and the Roman province of Dacia. In 275 AD, Aurelian surrendered the Dacian territory [clarification needed] to the Carpi and the Goths. Over time, Gothic power in the region grew, at the Carpi's expense. The Germanic-speaking Goths replaced native Dacian-speakers as the dominant force around the Carpathian mountains. Large numbers of Carpi, but not all of them, were admitted into the Roman empire in the twenty-five years or so after 290 AD. Despite this evacuation of the Carpi around 300 AD, considerable groups of the natives (non-Romanized Dacians, Sarmatians and others) remained in place under Gothic domination.

In 330 the Gothic Thervingi contemplated moving to the Middle Danube region, [citation needed] and from 370 relocated with their fellow Gothic Greuthungi to new homes in the Roman Empire. The Ostrogoths were still more isolated, but even the Visigoths preferred to live among their own kind. As a result, the Goths settled in pockets. Finally, although Roman towns continued on a reduced level, there is no question as to their survival.

In 336 AD, Constantine took the title Dacicus Maximus ("The great victory over Dacians"), implying at least partial reconquest of Trajan Dacia. In an inscription of 337, Constantine was commemorated officially as Germanicus Maximus, Sarmaticus, Gothicus Maximus, and Dacicus Maximus, meaning he had defeated the Germans, Sarmatians, Goths, and Dacians.

Dacian kingdoms :

Dacian polities arose as confederacies that included the Getae, the Daci, the Buri, and the Carpi [dubious – discuss] (cf. Bichir 1976, Shchukin 1989), united only periodically by the leadership of Dacian kings such as Burebista and Decebal. This union was both military-political and ideological-religious on ethnic basis. The following are some of the attested Dacian kingdoms :

The kingdom of Cothelas, one of the Getae, covered an area near the Black Sea, between northern Thrace and the Danube, today Bulgaria, in the 4th century BC. The kingdom of Rubobostes controlled a region in Transylvania in the 2nd century BC. Gaius Scribonius Curio (proconsul 75–73 BC) campaigned successfully against the Dardani and the Moesi, becoming the first Roman general to reach the river Danube with his army. His successor, Marcus Licinius Lucullus, brother of the famous Lucius Lucullus, campaigned against the Thracian Bessi tribe and the Moesi, ravaging the whole of Moesia, the region between the Haemus (Balkan) mountain range and the Danube. In 72 BC, his troops occupied the Greek coastal cities of Scythia Minor (the modern Dobrogea region in Romania and Bulgaria), which had sided with Rome's Hellenistic arch-enemy, king Mithridates VI of Pontus, in the Third Mithridatic War. Greek geographer Strabo claimed that the Dacians and Getae had been able to muster a combined army of 200,000 men during Strabo's era, the time of Roman emperor Augustus.

The

kingdom of Burebista :

The

kingdom of Decebalus 87 – 106 :

Conflict

with Rome :

The unifying actions of the last Dacian king Decebalus (ruled 87–106 AD) were seen as dangerous by Rome. Despite the fact that the Dacian army could now gather only some 40,000 soldiers, Decebalus' raids south of the Danube proved unstoppable and costly. In the Romans' eyes, the situation at the border with Dacia was out of control, and Emperor Domitian (ruled 81 to 96 AD) tried desperately to deal with the danger through military action. But the outcome of Rome's disastrous campaigns into Dacia in AD 86 and AD 88 pushed Domitian to settle the situation through diplomacy.

Emperor Trajan (ruled 97–117 AD) opted for a different approach and decided to conquer the Dacian kingdom, partly in order to seize its vast gold mines wealth. The effort required two major wars (the Dacian Wars), one in 101–102 AD and the other in 105–106 AD. Only fragmentary details survive of the Dacian war: a single sentence of Trajan's own Dacica; little more of the Getica written by his doctor, T. Statilius Crito; nothing whatsoever of the poem proposed by Caninius Rufus (if it was ever written), Dio Chrysostom's Getica or Appian's Dacica. Nonetheless, a reasonable account can be pieced together.

In the first war, Trajan invaded Dacia by crossing the river Danube with a boat-bridge and inflicted a crushing defeat on the Dacians at the Second Battle of Tapae in 101 AD. The Dacian king Decebalus was forced to sue for peace. Trajan and Decebalus then concluded a peace treaty which was highly favourable to the Romans. The peace agreement required the Dacians to cede some territory to the Romans and to demolish their fortifications. Decebalus' foreign policy was also restricted, as he was prohibited from entering into alliances with other tribes.

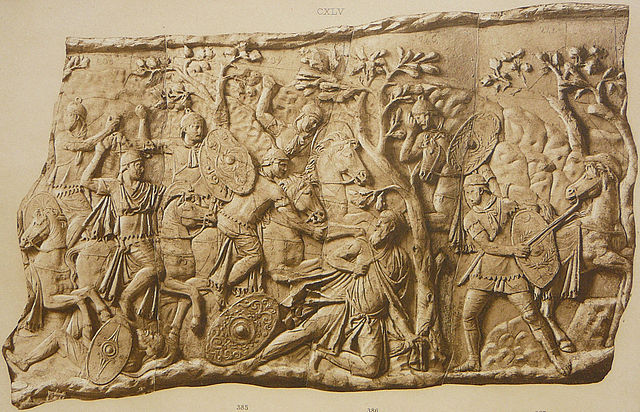

However, both Trajan and Decebalus considered this only a temporary truce and readied themselves for renewed war. Trajan had Greek engineer Apollodorus of Damascus construct a stone bridge over the Danube river, while Decebalus secretly plotted alliances against the Romans (citation needed). In 105, Trajan crossed the Danube river and besieged Decebalus' capital, Sarmizegetusa, but the siege failed because of Decebalus' allied tribes. However, Trajan was an optimist. He returned with a newly constituted army and took Sarmizegetusa by treachery. Decebalus fled into the mountains, but was cornered by pursuing Roman cavalry. Decebalus committed suicide rather than being captured by the Romans and be paraded as a slave, then be killed. The Roman captain took his head and right hand to Trajan, who had them displayed in the Forums. Trajan's Column in Rome was constructed to celebrate the conquest of Dacia.

Death of Decebalus (Trajan's Column, Scene CXLV) The Roman people hailed Trajan's triumph in Dacia with the longest and most expensive celebration in their history, financed by a part of the gold taken from the Dacians. For his triumph, Trajan gave a 123-day festival (ludi) of celebration, in which approximately 11,000 animals were slaughtered and 11,000 gladiators fought in combats. This surpassed Emperor Titus's celebration in AD 70, when a 100-day festival included 3,000 gladiators and 5,000 to 9,000 wild animals.

Roman

rule :

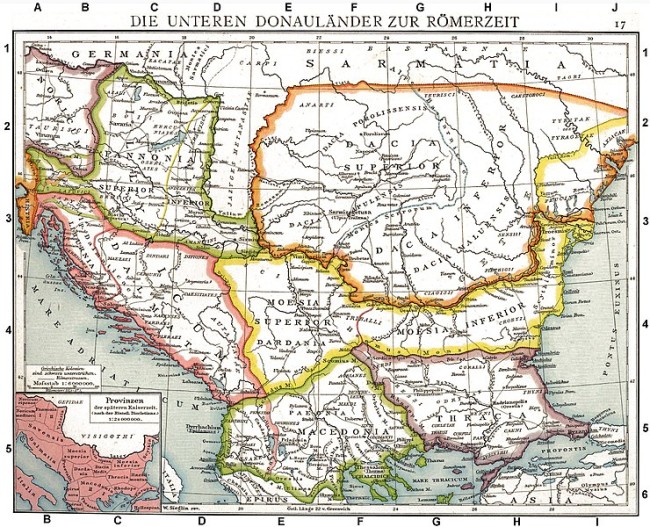

Roman Dacia, Moesia Inferior, Moesia Superior and other Roman provinces Dacians that remained outside the Roman Empire after the Dacian wars of AD 101–106 had been named Dakoi prosoroi (Latin Daci limitanei), "neighbouring Dacians". Modern historians use the generic name "Free Dacians" or Independent Dacians. The tribes Daci Magni (Great Dacians), Costoboci (generally considered a Dacian subtribe), and Carpi remained outside the Roman empire, in what the Romans called Dacia Libera (Free Dacia). By the early third century the "Free Dacians" were a significantly troublesome group, by now identified as the Carpi. Bichir argues that the Carpi were the most powerful of the Dacian tribes who had become the principal enemy of the Romans in the region. In 214 AD, Caracalla campaigned against the Free Dacians. There were also campaigns against the Dacians recorded in 236 AD.

Roman Dacia was evacuated by the Romans under emperor Aurelian (ruled 271–5 AD). Aurelian made this decision on account of counter-pressures on the Empire there caused by the Carpi, Visigoths, Sarmatians, and Vandals; the lines of defence needed to be shortened, and Dacia was deemed not defensible given the demands on available resources. Roman power in Thracia rested mainly with the legions stationed in Moesia. The rural nature of Thracia's populations, and the distance from Roman authority, encouraged the presence of local troops to support Moesia's legions. Over the next few centuries, the province was periodically and increasingly attacked by migrating Germanic tribes. The reign of Justinian saw the construction of over 100 legionary fortresses to supplement the defence. Thracians in Moesia and Dacia were Romanized, while those within the Byzantine empire were their Hellenized descendants that had mingled with the Greeks.

After the Aurelian Retreat :

Roman Dacia was never a uniformly or fully Romanized area. Post-Aurelianic Dacia fell into three divisions: the area along the river, usually under some type of Roman administration even if in a highly localized form; the zone beyond this area, from which Roman military personnel had withdrawn, leaving a sizable population behind that was generally Romanized; and finally what is now the northern parts of Moldavia, Crisana, and Maramures, which were never occupied by the Romans. These last areas were always peripheral to the Roman province, not militarily occupied but nonetheless influenced by Rome as part of the Roman economic sphere. Here lived the free, unoccupied Carpi, often called "Free Dacians".

The Aurelian retreat was a purely military decision to withdraw the Roman troops to defend the Danube. The inhabitants of the old province of Dacia displayed no awareness of impending dissolution. There were no sudden flights or dismantling of property. It is not possible to discern how many civilians followed the army out of Dacia; it is clear that there was no mass emigration, since there is evidence of continuity of settlement in Dacian villages and farms; the evacuation may not at first have been intended to be a permanent measure. The Romans left the province, but they didn't consider that they lost it. Dobrogea was not abandoned at all, but continued as part of the Roman Empire for over 350 years. As late as AD 300, the tetrarchic emperors had resettled tens of thousands of Dacian Carpi inside the empire, dispersing them in communities the length of the Danube, from Austria to the Black Sea.

Society :

Dacian tarabostes (nobleman) – (Hermitage Museum)

Comati on Trajan's Column, Rome Dacians were divided into two classes: the aristocracy (tarabostes) and the common people (comati). Only the aristocracy had the right to cover their heads, and wore a felt hat. The common people, who comprised the rank and file of the army, the peasants and artisans, might have been called capillati in Latin. Their appearance and clothing can be seen on Trajan's Column.

Occupations :

Dacian tools: compasses, chisels, knives, etc The chief occupations of the Dacians were agriculture, apiculture, viticulture, livestock, ceramics and metalworking. They also worked the gold and silver mines of Transylvania. At Pecica, Arad, a Dacian workshop was discovered, along with equipment for minting coins and evidence of bronze, silver, and iron-working that suggests a broad spectrum of smithing. Evidence for the mass production of iron is found on many Dacian sites, indicating guild-like specialization. Dacian ceramic manufacturing traditions continue from the pre-Roman to the Roman period, both in provincial and unoccupied Dacia, and well into the fourth and even early fifth centuries. They engaged in considerable external trade, as is shown by the number of foreign coins found in the country. On the northernmost frontier of "free Dacia", coin circulation steadily grew in the first and second centuries, with a decline in the third and a rise again in the fourth century; the same pattern as observed for the Banat region to the southwest. What is remarkable is the extent and increase in coin circulation after Roman withdrawal from Dacia, and as far north as Transcarpathia.

Currency :

Geto-Dacian Koson, mid 1st century BC The first coins produced by the Geto-Dacians were imitations of silver coins of the Macedonian kings Philip II and Alexander the Great. Early in the 1st century BC, the Dacians replaced these with silver denarii of the Roman Republic, both official coins of Rome exported to Dacia, as well as locally made imitations of them. The Roman province Dacia is represented on the Roman sestertius coin as a woman seated on a rock, holding an aquila, a small child on her knee. The aquila holds ears of grain, and another small child is seated before her holding grapes.

Construction :

Dacians had developed the murus dacicus (double-skinned ashlar-masonry with rubble fill and tie beams) characteristic to their complexes of fortified cities, like their capital Sarmisegetuza Regia in what is today Hunedoara County, Romania. This type of wall has been discovered not only in the Dacian citadel of the Orastie mountains, but also in those at Covasna, Breaza near Fagaras, Tilisca near Sibiu, Capâlna in the Sebes valley, Banita not far from Petrosani, and Piatra Craivii to the north of Alba Iulia. The degree of their urban development was displayed on Trajan's Column and in the account of how Sarmizegetusa Regia was defeated by the Romans. The Romans were given by treachery the locations of aqueducts and pipelines of the Dacian capital, only after destroying the water supply being able to end the long siege of Sarmisegetuza.

Material

culture :

Specific Dacian material culture includes: wheel-turned pottery that is generally plain but with distinctive elite wares, massive silver dress fibulae, precious metal plate, ashlar masonry, fortifications, upland sanctuaries with horseshoe-shaped precincts, and decorated clay heart altars at settlement sites. Among many discovered artifacts, the Dacian bracelets stand out, depicting their cultural and aesthetic sense. There are difficulties correlating funerary monuments chronologically with Dacian settlements; a small number of burials are known, along with cremation pits, and isolated rich burials as at Cugir. Dacian burial ritual continued under Roman occupation and into the post-Roman period.

Language

:

The ancient languages of these people became extinct, and their cultural influence highly reduced, after the repeated invasions of the Balkans by Celts, Huns, Goths, and Sarmatians, accompanied by persistent hellenization, romanisation and later slavicisation. Therefore, in the study of the toponomy of Dacia, one must take account of the fact that some place-names were taken by the Slavs from as yet unromanised Dacians. A number of Dacian words are preserved in ancient sources, amounting to about 1150 anthroponyms and 900 toponyms, and in Discorides some of the rich plant lore of the Dacians is preserved along with the names of 42 medicinal plants.

Symbols

:

Religion :

Dacian religion was considered by the classic sources as a key source of authority, suggesting to some that Dacia was a predominantly theocratic state led by priest-kings. However, the layout of the Dacian capital Sarmizegethusa indicates the possibility of co-rulership, with a separate high king and high priest. Ancient sources recorded the names of several Dacian high priests (Deceneus, Comosicus and Vezina) and various orders of priests: "god-worshipers", "smoke-walkers" and "founders". Both Hellenistic and Oriental influences are discernible in the religious background, alongside chthonic and solar motifs.

According to Herodotus' account of the story of Zalmoxis or Zamolxis, the Getae (speaking the same language as the Dacians and the Thracians, according to Strabo) believed in the immortality of the soul, and regarded death as merely a change of country. Their chief priest held a prominent position as the representative of the supreme deity, Zalmoxis, who is called also Gebeleizis by some among them. Strabo wrote about the high priest of King Burebista Deceneus: "a man who not only had wandered through Egypt, but also had thoroughly learned certain prognostics through which he would pretend to tell the divine will; and within a short time he was set up as god (as I said when relating the story of Zamolxis)."

Votive stele representing Bendis wearing a Dacian cap (British Museum) The Goth Jordanes in his Getica (The origin and deeds of the Goths), also gives an account of Deceneus the highest priest, and considered Dacians a nation related to the Goths. Besides Zalmoxis, the Dacians believed in other deities, such as Gebeleizis, the god of storm and lightning, possibly related to the Thracian god Zibelthiurdos. He was represented as a handsome man, sometimes with a beard. Later Gebeleizis was equated with Zalmoxis as the same god. According to Herodotus, Gebeleizis (*Zebeleizis/Gebeleizis who is only mentioned by Herodotus) is just another name of Zalmoxis.

Another important deity was Bendis, goddess of the moon and the hunt. By a decree of the oracle of Dodona, which required the Athenians to grant land for a shrine or temple, her cult was introduced into Attica by immigrant Thracian residents, and, though Thracian and Athenian processions remained separate, both cult and festival became so popular that in Plato's time (c. 429–13 BC) its festivities were naturalised as an official ceremony of the Athenian city-state, called the Bendideia.

Known Dacian theonyms include Zalmoxis, Gebeleïzis and Darzalas. Gebeleizis is probably cognate to the Thracian god Zibelthiurdos (also Zbelsurdos, Zibelthurdos), wielder of lightning and thunderbolts. Derzelas (also Darzalas) was a chthonic god of health and human vitality. The pagan religion survived longer in Dacia than in other parts of the empire; Christianity made little headway until the fifth century.

Pottery :

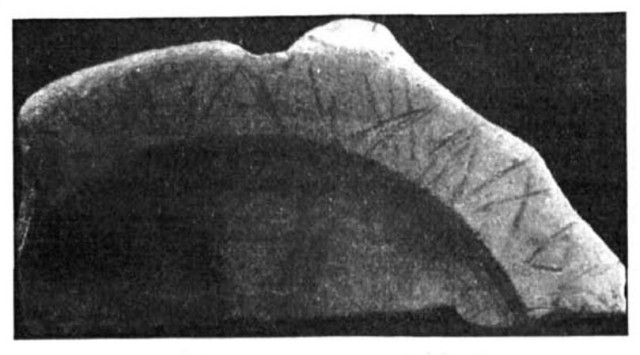

Fragment

of a vase collected by Mihail Dimitriu at the site of Poiana, Galati

(Piroboridava), Romania illustrating the use of Greek and Latin

letters by a Dacian potter (source: Dacia journal, 1933).

Clothing

and science :

Dio Chrysostom described the Dacians as natural philosophers.

A 19th century depiction of Dacian women

Warfare :

Weapons

:

Notable

individuals :

•

Zalmoxis, a semi-legendary

social and religious reformer, eventually deified by the Getae and

Dacians and regarded as the only true god.

In Romanian nationalism :

Study of the Dacians, their culture, society and religion is not purely a subject of ancient history, but has present day implications in the context of Romanian nationalism. Positions taken on the vexed question of the Origin of the Romanians and to what degree are present-day Romanians descended from the Dacians might have contemporary political implications. For example, The government of Nicolae Ceausescu claimed an uninterrupted continuity of a Dacian-Romanian state, from King Burebista to Ceausescu himself. The Ceausescu government conspicuously commemorated the supposed 2,050th anniversary of the founding of the "unified and centralized" country that was to become Romania, on which occasion the historical film "Burebista" was produced.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |