| FERGANA VALLEY

Fergana Valley (highlighted), post-1991 national territories colour-coded Location

: Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan

The Fergana Valley is a valley in Central Asia spread across eastern Uzbekistan, southern Kyrgyzstan and northern Tajikistan.

Divided into three republics of the former Soviet Union, the valley is ethnically diverse and in the early 21st century was the scene of ethnic conflict. A large triangular valley in what is an often dry part of Central Asia, the Fergana owes its fertility to two rivers, the Naryn and the Kara Darya, which run from the east, joining near Namangan, forming the Syr Darya river. The valley's history stretches back over 2,300 years, when Alexander the Great founded Alexandria Eschate at its southwestern end.

Chinese chroniclers date its towns to more than 2,100 years ago, as a path between Greek, Chinese, Bactrian and Parthian civilisations. It was home to Babur, founder of the Mughal Dynasty, tying the region to modern Afghanistan and South Asia. The Russian Empire conquered the valley at the end of the 19th century, and it became part of the Soviet Union in the 1920s. Its three Soviet republics gained independence in 1991. The area largely remains Muslim, populated by ethnic Uzbek, Tajik and Kyrgyz people, often intermixed and not matching modern borders. Historically there have also been substantial numbers of Russian, Kashgarians, Kipchaks, Bukharan Jews and Romani minorities.

Mass cotton cultivation, introduced by the Soviets, remains central to the economy, along with a wide range of grains, fruits and vegetables. There is a long history of stock breeding, leatherwork and a growing mining sector, including deposits of coal, iron, sulfur, gypsum, rock-salt, naphtha and some small known oil reserves.[citation needed]

Name

:

•

Uzbek : Farg‘ona

vodiysi

Fergana Valley on map showing Sakastan about 100 BC The Fergana Valley is an intermountain depression in Central Asia, between the mountain systems of the Tien-Shan in the north and the Gissar-Alai in the south. The valley is approximately 300 kilometres (190 mi) long and up to 70 kilometres (43 mi) wide, forming an area covering 22,000 square kilometres (8,500 sq mi). Its position makes it a separate geographic zone. The valley owes its fertility to two rivers, the Naryn and the Kara Darya, which unite in the valley, near Namangan, to form the Syr Darya. Numerous other tributaries of these rivers exist in the valley including the Sokh River. The streams, and their numerous mountain effluents, not only supply water for irrigation, but also bring down vast quantities of sand, which is deposited alongside their courses, more especially alongside the Syr Darya where it cuts its way through the Khujand-Ajar ridge and forms the valley. This expanse of quicksand, covering an area of 1,900 km2 (750 sq mi), under the influence of south-west winds, encroaches upon the agricultural districts.

The central part of the geological depression that forms the valley is characterized by block subsidence, originally to depths estimated at 6 to 7 kilometres (3.7 to 4.3 mi), largely filled with sediments that range in age as far back as the Permian-Triassic boundary. Some of the sediments are marine carbonates and clays. The faults are upthrusts and overthrusts. Anticlines associated with these faults form traps for petroleum and natural gas, which has been discovered in 52 small fields.

Climate

:

History

:

Achaemenid

Empire :

Hellenistic settlement :

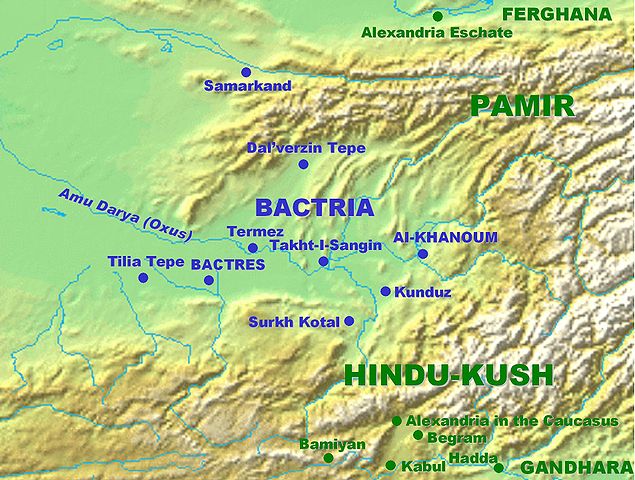

In 329 BC, Alexander the Great founded a Greek settlement with the city of Alexandria Eschate "The Furthest", in the southwestern part of the Fergana Valley, on the southern bank of the river Syr Darya (ancient Jaxartes), at the location of the modern city of Khujand, in the state of Tajikistan. It was later ruled by Seleucids before secession of Bactria.

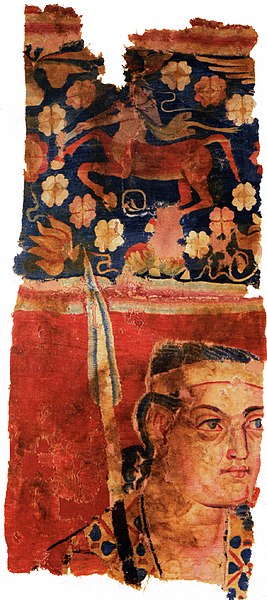

After 250 BC, the city probably remained in contact with the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom centered on Bactria, especially when the Greco-Bactrian king Euthydemus extended his control to Sogdiana. There are indications that from Alexandria Eschate the Greco-Bactrians may have led expeditions as far as Kashgar and Ürümqi in Chinese Turkestan, leading to the first known contacts between China and the West around 220 BC. Several statuettes and representations of Greek soldiers have been found north of the Tian Shan, on the doorstep to China, and are today on display in the Xinjiang museum at Urumqi (Boardman). Of the Greco-Bactrians, the Greek historian Strabo too writes that :

they extended their empire even as far as the Seres (Chinese) and the Phryni.

The Fergana area, called Dayuan by the Chinese, remained an integral part of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom until after the time of Demetrius I of Bactria (c. 120 BC), when confronted with invasions by the Yuezhi from the east and the Sakas Scythians from the south. After 155 BC, the Yuezhi were pushed into Fergana by neighbors from the north and east. The Yuezhi invaded urban civilization of the Dayuan in Fergana, eventually settling on the northern bank of the Oxus, in the region of Transoxiana, in modern-day Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, just north of the Hellenistic Greco-Bactrian kingdom. The Greek city of Alexandria on the Oxus was apparently burnt to the ground by the Yuezhi around 145 BC. Pushed by these twin forces, the Greco-Bactrian kingdom reoriented itself around lands in what is now Afghanistan, while the new invaders were partially assimilated into the Hellenistic culture left in Fergana Valley.

Han

dynasty :

The Dayuan were identified by the Chinese as unusual in features, with a sophisticated urban civilization, similar to that of the Bactrians and Parthians: "The Son of Heaven on hearing all this reasoned thus: Fergana (Dayuan) and the possessions of Bactria and Parthia are large countries, full of rare things, with a population living in fixed abodes and given to occupations somewhat identical with those of the Chinese people, but with weak armies, and placing great value on the rich produce of China" (Book of the Later Han). Agricultural activities of the Dayuan reported by Zhang Qian included cultivation of grain and grapes for wine-making. The area of Fergana was thus the theater of the first major interaction between an urbanized culture speaking Indo-European languages and the Chinese civilization, which led to the opening up the Silk Road from the 1st century BC onwards.

The Han later captured Dayuan in the Han-Dayuan war, installing a king there. Later the Han set up the Protectorate of the Western Regions

Kushan :

Ancient cities of Bactria. Fergana, to the top right, formed a periphery to these less powerful cities and states The Kushan Empire formed from the same Yuezhi who had conquered the Hellenistic Fergana. The Kushan spread out in the 1st century AD from the Yuezhi confederation in the territories of ancient Bactria on either side of the middle course of the Oxus River or Amu Darya in what is now northern Afghanistan, and southern Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. The Kushan conquered most of what is now northern India and Pakistan, driving east through Fergana. Kushan power also consolidated long distance trade, linking Central Asia to both Han Dynasty China and the Roman Empire in Europe.

Sassanid

(3rd - 5th centuries) :

Hepthalites

:

Gokturks

:

Ikhshids

:

The Umayyad Caliphate in 715 desposed the ruler, and installed a new king Alutar on the throne. The Chinese sent 10,000 troops under Zhang Xiaosong to Ferghana. He defeated Alutar and the Arab occupation force at Namangan and reinstalled Ikhshid on the throne.

Islamic

invasions :

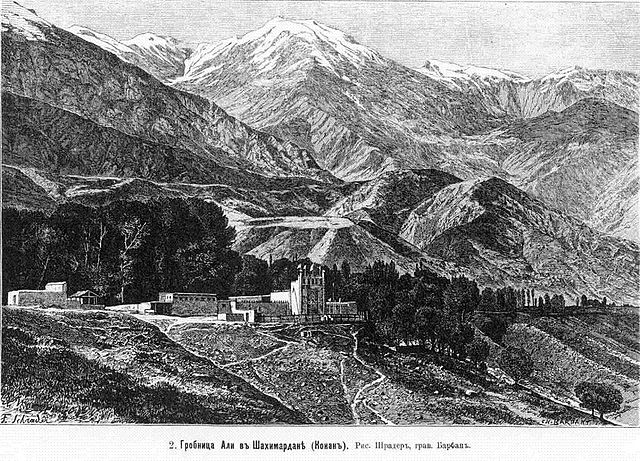

The tomb of Ali at Shakhimardan

Samanid, Karakhanid and Khwarezmid rules :

By the time of Ahmad's death in 864 or 865, he was the ruler of most of Transoxiana, Bukhara and Khwarazm. Samarkand and Fergana went to his son, Nasr I of Samanid, leading to a series of Samanid Dynasty Muslim rulers of the valley. During demise of Samanids in 10th century, Fergana Valley was conquered by Karakhanids. Eastern part of Fergana later was under suzerenaity of Karakhitays. Karakhanid rule lasted till 1212, when Khwarezmshahs conquered the western part of the valley.

Mongol–Turkic rule :

Babur, the Turco-Mongol founder of the Mughal dynasty, was a native of Andijan in the Fergana Valley Mongol ruler Genghis Khan invaded Transoxiana and Fergana in 1219 during his conquest of Khwarazm. Before his death in 1227, he assigned the lands of Western Central Asia to his second son Chagatai, and this region became known as the Chagatai Khanate. But it was not long before Transoxian Turkic leaders ruled the area, along with most of central Asia as fiefs from the Golden Horde of the Mongol Empire. The Fergana became part of a larger Turco-Mongol empire. This Mongolian nomadic confederation known as Barlas, were remnants of the original Mongol army of Genghis Khan.

After the Mongol conquest of Central Asia, the Barlas settled in Turkistan (which then became also known as Moghulistan - "Land of Mongols") and intermingled to a considerable degree with the local Turkic and Turkic-speaking population, so that at the time of Timur's reign the Barlas had become thoroughly Turkicized in terms of language and habits. Additionally, by adopting Islam, the Central Asian Turks and Mongols also adopted the Persian literary and high culture which had dominated Central Asia since the early days of Islamic influence. Persian literature was instrumental in the assimilation of the Timurid elite to the Perso-Islamic courtly culture.

Heir to one of these confederations, Timur, founder of the Timurid dynasty, added the valley to a newly consolidated empire in the late 14th century, ruling the area from Samarkand.

Located on the Northern Silk Road, the Fergana played a significant part in the flowering of medieval Central Asian Islam. Its most famous son is Babur, heir to Timur and famous conqueror and founder of the Mughal dynasty in Medieval India. Islamic proselytizers from the Fergana Valley such as al-Firghani, al-Andijan, al-Namangani, al-Khojandi spread Islam into parts of present-day Russia, China, and India.

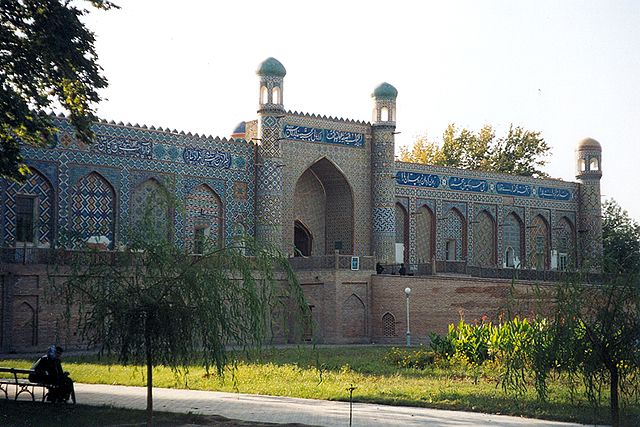

The Fergana valley was ruled by a series of Muslim states in the medieval period. For much of this period local and southwestern rulers divided the valley into a series of small states. From the 16th century, the Shaybanid Dynasty of the Khanate of Bukhara ruled Fergana, replaced by the Janid Dynasty of Bukhara in 1599. In 1709 Shaybanid emir Shahrukh of the Minglar Uzbeks declared independence from the Khanate of Bukhara, establishing a state in the eastern part of the Fergana Valley. He built a citadel to be his capital in the small town of Kokand. As the Khanate of Kokand, Kokand was capital of a territory stretching over modern eastern Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, southern Kazakhstan and all of Kyrgyzstan.

Russian Empire :

Khan's Palace, Kokand Fergana was a province of Russian Turkestan, formed in 1876 out of the former khanate of Kokand. It was bounded by the provinces of Syr-darya in the North and Northwest, Samarkand in the West, and Zhetysu in the Northeast, by Chinese Turkestan (Kashgaria) in the East, and by Bukhara and Afghanistan in the South. Its southern limits, in the Pamirs, were fixed by an Anglo-Russian commission in 1885, from Zorkul (Victoria Lake) to the Chinese frontier; and Khignan, Roshan and Wakhan were assigned to Afghanistan in exchange for part of Darvaz (on the left bank of the Panj), which was given to Bukhara. The area amounted to some 53,000 km2 (20,463 sq mi), of which 17,600 km2 (6,795 sq mi) are in the Pamirs.

Not all the inhabitants of the area were happy with this state of affairs. In 1898 Muhammed Ali Khalfa proclaimed a jihad against the Russians. However, after about 20 Russians had been killed, Khalfa was captured and executed. When the 1905 Revolution spread across the Russian Empire, some Jadids were active in the Fergana Valley. When the Tsarist regime extended the military draft to include Muslims, this led to a revolt which was far more widespread than that of 1898, and which was not entirely suppressed by the time of the Russian Revolution.[citation needed]

Soviet Union :

Soviet negotiations with basmachi, Fergana, 1921 In 1924, the new boundaries separating the Uzbek SSR and Kyrgyz SSR cut off the eastern end of the Fergana Valley, as well as the slopes surrounding it. This was compounded in 1928 when the Tajik ASSR became a fully-fledged republic, and the area around Khujand was made a part of it. This blocked the valley's natural outlet and the routes to Samarkand and Bukhara, but none of these borders was of any great significance so long as Soviet rule lasted. The whole region was part of a single economy geared to cotton production on a massive scale, and the overarching political structures meant that crossing borders was not a problem.

Post

Soviet breakup :

People in the Tajikistan city of Khujand traveling to the Tajik capital of Dushanbe, unable to take the more direct route through Uzbekistan, have to cross a high mountain pass between the two cities instead, along a terrible road. Communications between the Kyrgyzstan cities of Bishkek and Osh pass through difficult mountainous country. Ethnic tensions also flared into riots in 1990, most notably in the town of Uzgen, near Osh. There has been no further ethnic violence, and things appeared to have quieted down for several years.

However, the valley is a religiously conservative region which was particularly hard-hit by President Karimov's secularization legislation in Uzbekistan, together with his decision to close the borders with Kyrgyzstan in 2003. This devastated the local economy by preventing the importation of cheap Chinese consumer goods. The deposition of Askar Akayev in Kyrgyzstan in April 2005, coupled with the arrest of a group of prominent local businessmen brought underlying tensions to a boil in the region around Andijan and Qorasuv during the May 2005 unrest in Uzbekistan in which hundreds of protestors were killed by troops. There was violence again in 2010 in the Kyrgyz part of the valley, heated by ethnic tensions, worsening economic conditions due to the global economic crisis, and political conflict over the ouster of Kyrgyz President Kurmanbek Bakiyev in April 2010. In June 2010, about 200 people have been reported to be killed during clashes in Osh and Jalal-Abad, and 2000 more were injured. Between 100,000 and 300,000 refugees, predominantly of Uzbek ethnic origin, attempted to flee to Uzbekistan, causing a major humanitarian crisis.[citation needed]

The area has also been subject to informal radicalization.[clarification needed]

Agriculture :

Confluence of Naryn and Kara Darya seen from space (false color). Many irrigated agricultural fields can be seen In Tsarist times, out of some 1,200,000 ha (3,000,000 acres) of cultivated land, about two thirds were under constant irrigation and the remaining third under partial irrigation. The soil was considered by the author of the 1911 Britannica article to be admirably cultivated, the principal crops having been cotton, wheat, rice, barley, maize, millet, lucerne, tobacco, vegetables and fruit. Gardening was conducted with a high degree of skill and success. Large numbers of horses, cattle and sheep were kept, and a good many camels are bred. Over 6,900 ha (17,000 acres) were planted with vines, and some 140,000 ha (350,000 acres) were under cotton.

Nearly 400,000 ha (1,000,000 acres) were covered with forests. The government maintained a forestry farm at Marghelan, from which 120,000 to 200,000 young trees were distributed free every year amongst the inhabitants of the province. Silkworm breeding, formerly a prosperous industry, had decayed, despite the encouragement of a state farm at New Marghelan.

Industry

:

Trade

:

The most famous export from the region were the 'blood-sweating' Heavenly Horses which so captured the imagination of the Chinese during the Han dynasty, but in fact these were almost certainly bred on the Steppe, either west of Bukhara or north of Tashkent, and merely brought to Fergana for sale. In the 19th century, not surprisingly, a considerable trade carried on with Russia; raw cotton, raw silk, tobacco, hides, sheepskins, fruit and cotton and leather goods were exported, and manufactured wares, textiles, tea and sugar were imported and in part re-exported to Kashgaria and Bokhara. The total trade of Fergana reached an annual value of nearly £3.5 million in 1911. Nowadays it suffers from the same depression that affects all trade that either originates in or has to pass through Uzbekistan. The only significant international export is cotton, although the Daewoo plant in Andizhan sends cars all over Uzbekistan.[citation needed]

Transport :

The Syr Darya river bridge at Khujand, Tajikistan, in the far west of the Fergana Valley Until the late 19th century, Fergana, like everywhere else in Central Asia, was dependent on the camel, horse and donkey for transport, while roads were few and bad. The Russians built a trakt or post-road linking Andijan, Kokand, Margilan and Khujand with Samarkand and Tashkent in the early 1870s. A new impulse was given to trade by the extension (1898) of the Transcaspian railway into Fergana as far as Andijan, and by the opening of the Orenburg-Tashkent or Trans-Aral Railway in (1906).

Until Soviet times and the construction of the Pamir Highway from Osh to Khorog in the 1920s the routes to Kashgaria and the Pamirs were mere bridle-paths over the mountains, crossing them by lofty passes. For instance, the passes of Kara-kazyk, 4,389 m (14,400 ft) and Tenghiz-bai 3,413 m (11,200 ft), both passable all the year round, lead from Marghelan to Karateghin and the Pamirs, while Kashgar is reached via Osh and Gulcha, and then over the passes of Terek-davan, 3,720 m (12,205 ft); (open all the year round), Taldyk, 3,505 m (11,500 ft), Archat, 3,536 m (11,600 ft), and Shart-davan, 4,267 m (14,000 ft). Other passes leading out of the valley are the Jiptyk, 3,798 m (12,460 ft), S. of Kokand; the Isfairam, 3,657 m (12,000 ft), leading to the glen of the Surkhab, and the Kavuk, 3,962 m (13,000 ft), across the Alai Mountains.

The Angren-Pap railway line was completed in 2016 (together with the Kamchiq Tunnel), giving the region a direct railroad connection to the rest of Uzbekistan.

The Pap-Namangan-Andijon railway line is going to be electrified.

Historical

demography :

The population was estimated at 1,796,500 in 1906; two-thirds were Sarts and Uzbek. They lived mostly in the valley, while the mountain slopes above it were occupied by Kyrgyz, partly nomadic and pastoral, partly agricultural and settled. The other nations were Kashgarians, Kipchaks, Bukharan Jews and Gypsies. The governing class was primarily Russian, who also constituted much of the merchants and industrial working class. However, another merchant class in West Turkestan were commonly known as the Andijanis, from the town of Andijan in Fergana. The majority of the population were Muslims (1,039,115 in 1897).

The divisions revealed by the 1897 census, between a largely Tajik-speaking area around Khuhand, hill-regions populated by Kyrgyz and a settled, population in the main body of the valley, roughly reflect the borders as drawn after 1924. One exception is the town of Osh, which had a majority Uzbek population but ended up in Kyrgyzstan.

The one significant element that is missing when looking at modern accounts of the region are the Sarts. This term Sart was abolished by the Soviets as derogatory, but in fact there was a clear distinction between long-settled, Persianised Turkic peoples, speaking a form of Qarluq Turkic that is very close to Uyghur, and those who called themselves Uzbeks, who were a Kipchak tribe speaking a Turkic dialect much closer to Kazakh, who arrived in the region with Shaibani Khan in the mid-16th century. [citation needed] That this difference existed and was felt in Fergana is attested to in Timur Beisembiev's recent translation of the Life of Alimqul (London, 2003). [citation needed] There were few Kipchak-Uzbeks in Fergana, although they had at various times held political power in the region. In 1924, however, Soviet policy decreed that all settled Turks in Central Asia would thenceforth be known as "Uzbeks," (although the language chosen for the new Republic was not Kipchak but Qarluq) and the Fergana Valley is now seen as an Uzbek heartland.[citation needed]

Administrative

divisions :

The Valley is now divided between Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. In Tajikistan it is part of Soghd Region or vilayat, with the capital at Khujand. In Uzbekistan it is divided between the Namangan, Andijan and Fergana viloyati, while in Kyrgyzstan it contains parts of Batken, Jalal-abad and Osh oblasts, with Osh being the main town for the southern part of the country.[citation needed]

Cities in the Fergana Valley include :

• Uzbekistan

• Kyrgyzstan

• Tajikistan

Border

disputes :

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, border negotiations left substantial Uzbek populations stranded outside of Uzbekistan. In south-western Kyrgyzstan, a conflict over land between Kyrgyz and Uzbeks exploded in 1990 into large-scale ethnic violence; the violence reoccurring in 2010. By establishing political units on a mono-ethnic basis in a region where various peoples have historically lived side by side, the Soviet process of national delimitation sowed the seeds of today's inter-ethnic tensions.

Conflicts over water have contributed to border disputes. For instance, the border between Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan in Jalal-Abad Region is kept open in a limited way to help irrigation, however inter-ethnic disputes in border regions often turn into national border disputes. Even during the summer there are border conflicts over water, as there is not enough to share.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |