| GILGIT - BALTISTAN

Attabad Lake, K2

Attabad Lake, K2

Gilgit-Baltistan shown within Pakistan (hatched regions indicate claimed but not controlled territories)

A map of the disputed Kashmir region with the two Pakistani-administered territories shown in green Gilgit-Baltistan

Region administered by Pakistan as an administrative territory

Coordinates : 35.35° N 75.9° E

Administering Country : Pakistan Established : 1 November 1948

Capital : Gilgit

Largest city : Skardu

Government

• Type : Self-governing territory of Pakistan

• Body : Government of Gilgit-Baltistan

• Governor : Raja Jalal Hussain Maqpoon

• Chief Minister : Mir Afzal

• Chief Secretary : Muhammad Khuram Aga

• Legislature : Legislative assembly

• High Court : Gilgit-Baltistan Supreme Appellate Court

Area

• Total : 72,971 km2 (28,174 sq mi)

Population (2013)

• Total : 1,249,000

• Density : 17/km2 (44/sq mi)

Time zone : UTC+05:00 (PST) ISO 3166

Code : PK-GB

Languages : Balti, Shina, Wakhi, Burushaski, Khowar, Domaki, Urdu (administrative)

HDI (2018) : 0.593

Medium Assembly seats : 33

Divisions : 3

Districts : 14

Tehsils : 28 [citation needed]

Gilgit-Baltistan, formerly known as the Northern Areas, is a region administered by Pakistan as an administrative territory, and constituting the northern portion of the larger Kashmir region which has been the subject of a dispute between India and Pakistan since 1947, and between India and China from somewhat later. It is the northernmost territory administered by Pakistan. It borders Azad Kashmir to the south, the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa to the west, the Wakhan Corridor of Afghanistan to the north, the Xinjiang region of China, to the east and northeast, and the Indian-administered union territories Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh to the southeast.

Gilgit-Baltistan is part of the greater Kashmir region, which is the subject of a long-running conflict between Pakistan and India. The territory shares a border with Azad Kashmir, together with which it is referred to by the United Nations and other international organisations as "Pakistan administered Kashmir". Gilgit-Baltistan is six times the size of Azad Kashmir. The territory also borders Indian-administered union territories Jammu and Kashmir (union territory) and Ladakh to the south and is separated from it by the Line of Control, the de facto border between India and Pakistan.

The territory of present-day Gilgit-Baltistan became a separate administrative unit in 1970 under the name "Northern Areas". It was formed by the amalgamation of the former Gilgit Agency, the Baltistan district and several small former princely states, the larger of which being Hunza and Nagar. In 2009, it was granted limited autonomy and renamed to Gilgit-Baltistan via the Self-Governance Order signed by President of Pakistan Asif Ali Zardari, which also aimed to empower the people of Gilgit-Baltistan. However, scholars state that the real power rests with the governor and not with chief minister or elected assembly. Much of the population of Gilgit-Baltistan wants to be merged into Pakistan as a separate fifth province and opposes integration with Kashmir. The Pakistani government has rejected Gilgit-Baltistani calls for integration with Pakistan on the grounds that it would jeopardise its demands for the whole Kashmir issue to be resolved according to UN resolutions. However, in November 2020, Pakistan's Prime Minister Imran Khan announced that Gilgit-Baltistan would attain Provisional Provincial status after the 2020 Gilgit-Baltistan Assembly election, being a long-standing demand of the people of Gilgit-Baltistan.

Gilgit-Baltistan covers an area of over 72,971 km2 (28,174 sq mi) and is highly mountainous. It had an estimated population of 1.249 million in 2013 (estimated as 1.8 million in 2015 by Shahid Javed Burki (2015)). Its capital city is Gilgit (population 216,760 est). Gilgit-Baltistan is home to five of the "eight-thousanders" and more than fifty peaks above 7,000 metres (23,000 ft). Three of the world's longest glaciers outside the polar regions are found in Gilgit-Baltistan. The main tourism activities are trekking and mountaineering, and this industry is growing in importance.

Early history :

Rock carvings

Manthal Buddha Rock in outskirts of Skardu city

Photograph of Kargah Buddha

The Hanzal stup dates from the Buddhist era

"The ancient Stupa – rock carvings of Buddha, everywhere

in the region is a pointer to the firm hold of the Buddhist rules

for such a long time."

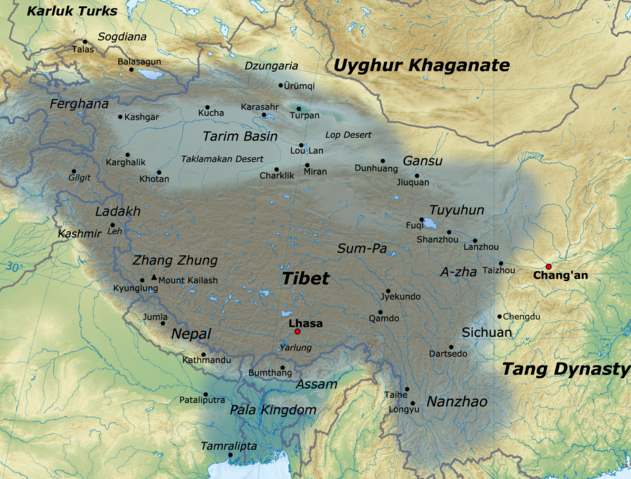

Map of Tibetan Empire citing the areas of Gilgit-Baltistan as part of its kingdom in 780 – 790 CE Between 399 and 414, the Chinese Buddhist pilgrim Faxian visited Gilgit-Baltistan, while in the 6th century Somana Palola (greater Gilgit-Chilas) was ruled by an unknown king. Between 627 and 645, the Chinese Buddhist pilgrim Xuanzang travelled through this region on his pilgrimage to India.

According to Chinese records from the Tang dynasty, between the 600s and the 700s, the region was governed by a Buddhist dynasty referred to as Bolü (Chinese: pinyin: bólu), also transliterated as Palola, Patola, Balur. They are believed to be the Palola Sahi dynasty mentioned in a Brahmi inscription, and are devout adherents of Vajrayan Buddhism. At the time, Little Palola was used to refer to Gilgit, while Great Palola was used to refer to Baltistan. However, the records do not consistently disambiguate the two.

In mid-600s, Gilgit came under Chinese suzerainty after the fall of Western Turkic Khaganate due to Tang military campaigns in the region. In the late 600s CE, the rising Tibetan Empire wrestled control of the region from the Chinese. However, faced with growing influence of the Umayyad Caliphate and then the Abbasid Caliphate to the west, the Tibetans were forced to ally themselves with the Islamic caliphates. The region was then contested by Chinese and Tibetan forces, and their respective vassal states, until the mid-700s. Rulers of Gilgit formed an alliance with the Tang Chinese and held back the Arabs with their help.

Between 644 and 655, Navasurendraditya-nandin became king of Palola Sahi dynasty in Gilgit. Numerous Sanskrit inscriptions, including the Danyor Rock Inscriptions, were discovered to be from his reign. In the late 600s and early 700s, Jaymangalvikramaditya-nandin was king of Gilgit.

According to Chinese court records, in 717 and 719 respectively, delegations of a ruler of Great Palola (Baltistan) named Su-fu-she-li-ji-li-ni (Chinese: pinyin: sufúshèlìzhilíní) reached the Chinese imperial court. By at least 719/720, Ladakh (Mard) became part of the Tibetan Empire. By that time, Buddhism was practised in Baltistan, and Sanskrit was the written language.

In 720, the delegation of Surendraditya (Chinese: pinyin: sulíntuóyìzhi) reached the Chinese imperial court. He was referred to by the Chinese records as the king of Great Palola; however, it is unknown if Baltistan was under Gilgit rule at the time. The Chinese emperor also granted the ruler of Cashmere, Chandrapida ("Tchen-fo-lo-pi-li"), the title of "King of Cashmere". By 721/722, Baltistan had come under the influence of the Tibetan Empire.

In 721–722, Tibetan army attempted but failed to capture Gilgit or Bruzha (Yasin valley). By this time, according to Chinese records, the king of Little Palola was Mo-ching-mang (Chinese: pinyin: méijinmáng). He had visited Tang court requesting military assistance against the Tibetans. Between 723–728, the Korean Buddhist pilgrim Hyecho passed through this area. In 737/738, Tibetan troops under the leadership of Minister Bel Kyesang Dongtsab of Emperor Me Agtsom took control of Little Palola. By 747, the Chinese army under the leadership of the ethnic-Korean commander Gao Xianzhi had recaptured Little Palola. Great Palola was subsequently captured by the Chinese army in 753 under the military Governor Feng Changqing. However, by 755, due to the An Lushan rebellion, the Tang Chinese forces withdrew and was no longer able to exert influence in Central Asia and in the regions around Gilgit-Baltistan. The control of the region was left to the Tibetan Empire. They referred to the region as Bruzha, a toponym that is consistent with the ethnonym "Burusho" used today. Tibetan control of the region lasted until late-800s CE.

Turkic tribes practising Zoroastrianism arrived in Gilgit during the 7th century, and founded the Trakhan dynasty in Gilgit.

Medieval

history :

Before the demise of Shribadat, a group of Shin people migrated from Gilgit Dardistan and settled in the Dras and Kharmang areas. The descendants of those Dardic people can be still found today, and are believed to have maintained their Dardic culture and Shina language up to the present time.[citation needed]

Modern

history :

The last Maqpon Raja Ahmed Shah (died in prison in Lhasa c. 1845) In November 1839, Dogra commander Zorawar Singh, whose allegiance was to Gulab Singh, started his campaign against Baltistan. By 1840 he conquered Skardu and captured its ruler, Ahmad Shah. Ahmad Shah was then forced to accompany Zorawar Singh on his raid into Western Tibet. Meanwhile, Baghwan Singh was appointed as administrator (Thanadar) in Skardu. But in the following year, Ali Khan of Rondu, Haidar Khan of Shigar and Daulat Ali Khan from Khaplu led a successful uprising against the Dogras in Baltistan and captured the Dogra commander Baghwan Singh in Skardu.

In 1842, Dogra Commander Wasir Lakhpat, with the active support of Ali Sher Khan (III) from lKartaksho, conquered Baltistan for the second time. There was a violent capture of the fortress of Kharphocho. Haidar Khan from Shigar, one of the leaders of the uprising against the Dogras, was imprisoned and died in captivity. Gosaun was appointed as administrator (Thanadar) of Baltistan and till 1860, the entire region of Gilgit-Baltistan was under the Sikhs and then the Dogras.

After the defeat of the Sikhs in the First Anglo-Sikh War, the region became a part of the princely state called Jammu and Kashmir which since 1846 remained under the rule of the Dogras. The population in Gilgit perceived itself to be ethnically different from Kashmiris and disliked being ruled by the Kashmir state. The region remained with the princely state, with temporary leases of some areas assigned to the British, until 1 November 1947.

First

Kashmir War :

Gilgit's population did not favour the State's accession to India. The Muslims of the Frontier Districts Province (modern day Gilgit-Baltistan) had wanted to join Pakistan. Sensing their discontent, Major William Brown, the Maharaja's commander of the Gilgit Scouts, mutinied on 1 November 1947, overthrowing the Governor Ghansara Singh. The bloodless coup d'etat was planned by Brown to the last detail under the code name "Datta Khel", which was also joined by a rebellious section of the Jammu and Kashmir 6th Infantry under Mirza Hassan Khan. Brown ensured that the treasury was secured and minorities were protected. A provisional government (Aburi Hakoomat) was established by the Gilgit locals with Raja Shah Rais Khan as the president and Mirza Hassan Khan as the commander-in-chief. However, Major Brown had already telegraphed Khan Abdul Qayyum Khan asking Pakistan to take over. The Pakistani political agent, Khan Mohammad Alam Khan, arrived on 16 November and took over the administration of Gilgit. Brown outmaneuvered the pro-Independence group and secured the approval of the mirs and rajas for accession to Pakistan. Browns's actions surprised the British Government.

According to Brown, Alam replied [to the locals], "you are a crowd of fools led astray by a madman. I shall not tolerate this nonsense for one instance... And when the Indian Army starts invading you there will be no use screaming to Pakistan for help, because you won't get it."... The provisional government faded away after this encounter with Alam Khan, clearly reflecting the flimsy and opportunistic nature of its basis and support.

The provisional government lasted 16 days. The provisional government lacked sway over the population. The Gilgit rebellion did not have civilian involvement and was solely the work of military leaders, not all of whom had been in favour of joining Pakistan, at least in the short term. Historian Ahmed Hasan Dani mentions that although there was a lack of public participation in the rebellion, pro-Pakistan sentiments were intense in the civilian population and their anti-Kashmiri sentiments were also clear. According to various scholars, the people of Gilgit as well as those of Chilas, Koh Ghizr, Ishkoman, Yasin, Punial, Hunza and Nagar joined Pakistan by choice.

After taking control of Gilgit, the Gilgit Scouts along with Azad irregulars moved towards Baltistan and Ladakh and captured Skardu by May 1948. They successfully blocked the Indian reinforcements and subsequently captured Dras and Kargil as well, cutting off the Indian communications to Leh in Ladakh. The Indian forces mounted an offensive in Autumn 1948 and recaptured all of Kargil district. Baltistan region, however, came under Gilgit control.

On 1 January 1948, India took the issue of Jammu and Kashmir to the United Nations Security Council. In April 1948, the Council passed a resolution calling for Pakistan to withdraw from all of Jammu and Kashmir and India to reduce its forces to the minimum level, following which a plebiscite would be held to ascertain the people's wishes. However, no withdrawal was ever carried out, India insisting that Pakistan had to withdraw first and Pakistan contending that there was no guarantee that India would withdraw afterwards. Gilgit-Baltistan and a western portion of the state called Azad Jammu and Kashmir have remained under the control of Pakistan since then.

Inside

Pakistan :

There were two reasons why administration was transferred from Azad Kashmir to Pakistan: (1) the region was inaccessible to Azad Kashmir and (2) because both the governments of Azad Kashmir and Pakistan knew that the people of the region were in favour of joining Pakistan in a potential referendum over Kashmir's final status.

According to the International Crisis Group, the Karachi Agreement is highly unpopular in Gilgit-Baltistan because Gilgit-Baltistan was not a party to it even while its fate was being decided upon.

From then until the 1990s, Gilgit-Baltistan was governed through the colonial-era Frontier Crimes Regulations, which treated tribal people as "barbaric and uncivilised," levying collective fines and punishments. People had no right to legal representation or a right to appeal. Members of tribes had to obtain prior permission from the police to travel to any location and had to keep the police informed about their movements. There was no democratic set-up for Gilgit-Baltistan during this period. All political and judicial powers remained in the hands of the Ministry of Kashmir Affairs and Northern Areas (KANA). The people of Gilgit-Baltistan were deprived of rights enjoyed by citizens of Pakistan and Azad Kashmir.

A primary reason for this state of affairs was the remoteness of Gilgit-Baltistan. Another factor was that the whole of Pakistan itself was deficient in democratic norms and principles, therefore the federal government did not prioritise democratic development in the region. There was also a lack of public pressure as an active civil society was absent in the region, with young educated residents usually opting to live in Pakistan's urban centers instead of staying in the region.

In 1970 the two parts of the territory, viz., the Gilgit Agency and Baltistan, were merged into a single administrative unit, and given the name "Northern Areas". The Shaksgam tract was ceded by Pakistan to China following the signing of the Sino-Pakistani Frontier Agreement in 1963. In 1969, a Northern Areas Advisory Council (NAAC) was created, later renamed to Northern Areas Council (NAC) in 1974 and Northern Areas Legislative Council (NALC) in 1994. But it was devoid of legislative powers. All law-making was concentrated in the KANA Ministry of Pakistan. In 1994, a Legal Framework Order (LFO) was created by the KANA Ministry to serve as the de facto constitution for the region.

In 1984 the territory's importance shot up on the domestic level with the opening of the Karakoram Highway and the region's population came to be more connected with mainland Pakistan. With the improvement in connectivity, the local population availed education opportunities in the rest of Pakistan. Improved connectivity also allowed the political parties of Pakistan and Azad Kashmir to set up local branches, raise political awareness in the region, and these Pakistani political parties have played a 'laudable role' in organising a movement for democratic rights among the residents of Gilgit-Baltistan.

In the late 1990s, the President of Al-Jihad Trust filed a petition in the Supreme Court of Pakistan to determine the legal status of Gilgit-Baltistan. In its judgement of 28 May 1999, the Court directed the Government of Pakistan to ensure the provision of equal rights to the people of Gilgit-Baltistan, and gave it six months to do so. Following the Supreme Court decision, the government took several steps to devolve power to the local level. However, in several policy circles, the point was raised that the Pakistani government was helpless to comply with the court verdict because of the strong political and sectarian divisions in Gilgit-Baltistan and also because of the territory's historical connection with the still disputed Kashmir region and this prevented the determination of Gilgit-Baltistan's real status.

A position of 'Deputy Chief Executive' was created to act as the local administrator, but the real powers still rested with the 'Chief Executive', who was the Federal Minister of KANA. "The secretaries were more powerful than the concerned advisors," in the words of one commentator. In spite of various reforms packages over the years, the situation is essentially unchanged. Meanwhile, public rage in Gilgit-Baltistan is "growing alarmingly." Prominent "antagonist groups" have mushroomed protesting the absence of civic rights and democracy. Pakistan government has been debating the grant of a provincial status to Gilgit-Baltistan.

According to Antia Mato Bouzas, the PPP-led Pakistani government has attempted a compromise through its 2009 reforms between its traditional stand on the Kashmir dispute and the demands of locals, most of whom may have pro-Pakistan sentiments. While the 2009 reforms have added to the self-identification of the region, they have not resolved the constitutional status of the region within Pakistan.

The people of Gilgit-Baltistan want to be merged into Pakistan as a separate fifth province, however, leaders of Azad Kashmir are opposed to any step to integrate Gilgit-Baltistan into Pakistan. The people of Gilgit-Baltistan oppose any integration with Kashmir and instead want Pakistani citizenship and constitutional status for their region.

Gilgit-Baltistan has been a member state of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization since 2008.

In September 2020, Pakistan decided to elevate Gilgit-Baltistan’s status to that of a full-fledged province.

Government

:

Government of Pakistan abolished State Subject Rule in Gilgit-Baltistan in 1974, which resulted in demographic changes in the territory. While administratively controlled by Pakistan since the First Kashmir War, Gilgit-Baltistan has never been formally integrated into the Pakistani state and does not participate in Pakistan's constitutional political affairs. On 29 August 2009, the Gilgit-Baltistan Empowerment and Self-Governance Order 2009, was passed by the Pakistani cabinet and later signed by the then President of Pakistan Asif Ali Zardari. The order granted self-rule to the people of Gilgit-Baltistan, by creating, among other things, an elected Gilgit-Baltistan Legislative Assembly and Gilgit-Baltistan Council. Gilgit-Baltistan thus gained a de facto province-like status without constitutionally becoming part of Pakistan. Currently, Gilgit-Baltistan is neither a province nor a state. It has a semi-provincial status. Officially, the Pakistan government has rejected Gilgit-Baltistani calls for integration with Pakistan on the grounds that it would jeopardise its demands for the whole Kashmir issue to be resolved according to UN resolutions. Some Kashmiri nationalist groups, such as the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front, claim Gilgit-Baltistan as part of a future independent state to match what existed in 1947. India, on the other hand, maintains that Gilgit-Baltistan is a part of the former princely state of Jammu and Kashmir that is "an integral part of the country [India]."

The Gilgit-Baltistan Police (GBP) is responsible for law enforcement in Gilgit-Baltistan. The mission of the force is the prevention and detection of crime, maintenance of law and order and enforcement of the Constitution of Pakistan.

Regions :

Gilgit-Baltistan is administered as three divisions

Fourteen districts in 2019 * Combined population of Skardu, Shigar, Kharmang and Roundu districts. Shigar and Kharmang Districts were carved out of Skardu District after 1998. The estimated population of Gilgit-Baltistan was about 1.8 million in 2015 and the overall population growth rate between 1998 and 2011 was 63.1% making it 4.85% annually.

Security

:

Geography and climate :

Naltar Lakes

Naltar Lake or Bashkiri Lake - I

Naltar Lake or Bashkiri Lake - II

Surface

elevation = 3050 – 3150 m

Gilgit-Baltistan borders Pakistan's Khyber Pukhtunkhwa province to the west, a small portion of the Wakhan Corridor of Afghanistan to the north, China's Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region to the northeast, the Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir to the southeast, and the Pakistani-administered state of Azad Jammu and Kashmir to the south.

Gilgit-Baltistan is home to all five of Pakistan's "eight-thousanders" and to more than fifty peaks above 7,000 metres (23,000 ft). Gilgit and Skardu are the two main hubs for expeditions to those mountains. The region is home to some of the world's highest mountain ranges. The main ranges are the Karakoram and the western Himalayas. The Pamir Mountains are to the north, and the Hindu Kush lies to the west. Amongst the highest mountains are K2 (Mount Godwin-Austen) and Nanga Parbat, the latter being one of the most feared mountains in the world.

Three of the world's longest glaciers outside the polar regions are found in Gilgit-Baltistan: the Biafo Glacier, the Baltoro Glacier, and the Batura Glacier. There are, in addition, several high-altitude lakes in Gilgit-Baltistan :

•

Sheosar Lake

in the Deosai Plains, Skardu

Satpara Lake, Skardu, in 2002

Upper Kachura Lake

A boat in Attabad Lake

Shangrila Lake, Skardu

Manthokha Waterfall Rock

art and petroglyphs :

The ethnologist Karl Jettmar has pieced together the history of the area from inscriptions and recorded his findings in Rock Carvings and Inscriptions in the Northern Areas of Pakistan and the later-released Between Gandhara and the Silk Roads — Rock Carvings Along the Karakoram Highway. Many of these carvings and inscriptions will be inundated and/or destroyed when the planned Basha-Diamir dam is built and the Karakoram Highway is widened.

Climate

:

There are towns like Gilgit and Chilas that are very hot during the day in summer yet cold at night and valleys like Astore, Khaplu, Yasin, Hunza, and Nagar, where the temperatures are cold even in summer.

Economy and resources :

Montage of Gilgit-Baltistan The economy of the region is primarily based on a traditional route of trade, the historic Silk Road. The China Trade Organization forum led the people of the area to actively invest and learn modern trade know-how from its Chinese neighbour Xinjiang. Later, the establishment of a chamber of commerce and the Sust dry port (in Gojal Hunza) are milestones. The rest of the economy is shouldered by mainly agriculture and tourism. Agricultural products are wheat, corn (maize), barley, and fruits. Tourism is mostly in trekking and mountaineering, and this industry is growing in importance.

In early September 2009, Pakistan signed an agreement with the People's Republic of China for a major energy project in Gilgit-Baltistan which includes the construction of a 7,000-megawatt dam at Bunji in the Astore District.

Mountaineering :

View of Laila Peak, which is located near Hushe Valley (a town in Khaplu)

The

Trango Towers offer some of the largest cliffs and most challenging

rock climbing in the world, and every year a number of expeditions

from all corners of the globe visit Karakoram to climb the challenging

granite.

Continued

...

Tourism :

Cold Desert, Skardu is the world's highest desert

Ambulance on Attabad Lake Hunza

Nanga Parbat, Astore

Rush Lake, Nagar, Pakistan

Sheosar Lake is in the western part of Deosai National Park Gilgit Baltistan is the capital of tourism in Pakistan. Gilgit Baltistan is home to some of the highest peaks in the world, including K2 the second highest peak in the world. Gilgit Baltistan's landscape includes mountains, lakes, glaciers and valleys. Gilgit Baltistan is not only known for its mountains — it is also visited for its landmarks, culture, history and people. K2 Basecamp, Deosai, Naltar, Fairy Meadows Bagrot Valley and Hushe valley are common places to visit in Gilgit Baltistan.

Transport :

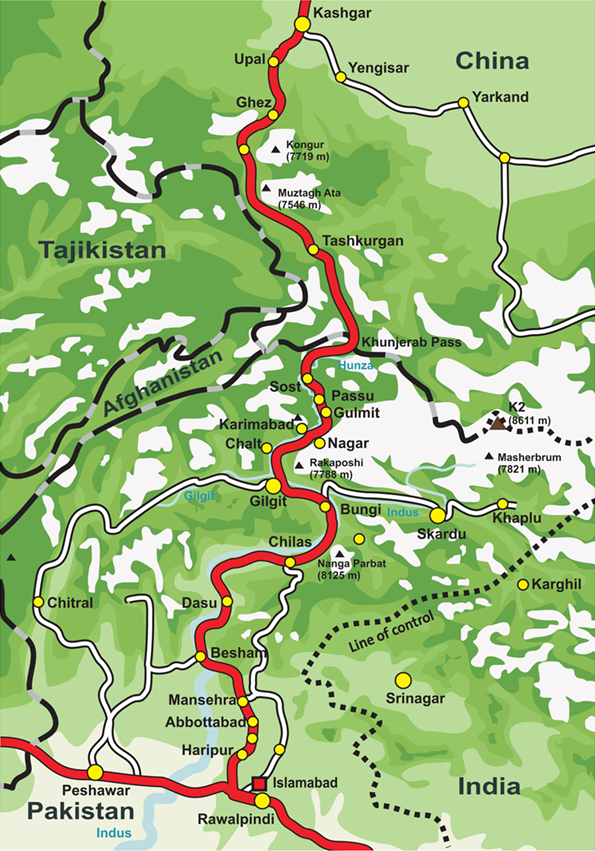

Tunnel Before 1978, Gilgit-Baltistan was cut off from the rest of the Pakistan and the world due to the harsh terrain and the lack of accessible roads. All of the roads to the south opened toward the Pakistan-administered state of Azad Kashmir and to the southeast toward the present-day Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir. During the summer, people could walk across the mountain passes to travel to Rawalpindi. The fastest way to travel was by air, but air travel was accessible only to a few privileged local people and to Pakistani military and civilian officials. Then, with the assistance of the Chinese government, Pakistan began construction of the Karakoram Highway (KKH), which was completed in 1978. The journey from Rawalpindi / Islamabad to Gilgit takes approximately 20 to 24 hours.

The Karakoram Highway

A view of Jaglote, Gore, from a tunnel on Karakoram Highway The Karakoram Highway connects Islamabad to Gilgit and Skardu, which are the two major hubs for mountaineering expeditions in Gilgit-Baltistan. Northern Areas Transport Corporation (NATCO) offers bus and jeep transport service to the two hubs and several other popular destinations, lakes, and glaciers in the area. Landslides on the Karakoram Highway are very common. The Karakoram Highway connects Gilgit to Tashkurgan Town, Kashgar, China via Sust, the customs and health-inspection post on the Gilgit-Baltistan side, and the Khunjerab Pass, the highest paved international border crossing in the world at 4,693 metres (15,397 ft).

In March 2006, the respective governments announced that, commencing on 1 June 2006, a thrice-weekly bus service would begin across the boundary from Gilgit to Kashgar and road-widening work would begin at 600 kilometres (370 mi) of the Karakoram Highway. There would also be one daily bus in each direction between the Sust and Taxkorgan border areas of the two political entities.

ATR 42–500 on Gilgit Airport. Picture taken on 10 July 2016 Pakistan International Airlines used to fly a Fokker F27 Friendship daily between Gilgit Airport and Benazir Bhutto International Airport. The flying time was approximately 50 minutes, and the flight was one of the most scenic in the world, as its route passed over Nanga Parbat, a mountain whose peak is higher than the aircraft's cruising altitude. However, the Fokker F27 was retired after a crash at Multan in 2006. Currently, flights are being operated by PIA to Gilgit on the brand-new ATR 42–500, which was purchased in 2006. With the new plane, the cancellation of flights is much less frequent. Pakistan International Airlines also offers regular flights of a Boeing 737 between Skardu and Islamabad. All flights are subject to weather clearance; in winter, flights are often delayed by several days.

A railway through the region has been proposed; see Khunjerab Railway for details.

Population

:

In 2017 census, Gilgit District has the highest population of 330,000 and Hunza District the lowest of 50,000.

Languages

:

Religion

:

Culture :

Architecture

Baltit fort, Hunza

Khaplu Palace

Chaqchan Mosque, Khaplu "Mostly the architecture have been influenced by Tibetan Architecture as the above images are testimonials of it."

Dance of Swati Guests with traditional music at Baltit Fort in 2014

Wakhi musicians in Gulmit

One of the poplular dish of this region is Chapchor. It is widely made in Hunza Valley Gilgit-Baltistan is home to diversified cultures, ethnic groups, languages and backgrounds. Major cultural events include the Shandoor Polo Festival, Babusar Polo Festival and Jashn-e-Baharan or the Harvest Time Festival (Navroz). Traditional dances include: Old Man Dance in which more than one person wears old-style dresses; Cow Boy Dance (Payaloo) in which a person wears old style dress, long leather shoes and holds a stick in hand and the Sword Dance in which the participants show taking one sword in right and shield in left. One to six participants can dance in pairs.

Sports :

Polo in progress with the shandur lake in background, Shandur Ghizer Many types of sports are in currency, throughout the region, but most popular of them is Polo. Almost every bigger valley has a polo ground, polo matches in such grounds attract locals as well as foreigners visitors during summer season. One of such polo tournament is held in Shandur each year and polo teams of Gilgit with Chitral participates. Though very internationally unlikely, but even for some local historians like Hassan Hasrat from Skardu and for some national writers like Ahmed Hasan Dani it was originated in same region. For testimonies, they present the Epic of King Gesar of balti version where king gesar started polo by killing his step son and hit head of cadaver with a stick thus started the game they also held that the very simple rules of local polo game also testifies its primitiveness. The English word Polo has balti origin, that is spoken in same region, dates back to the 19th century which means ball.

Other popular sports are football, cricket, volleyball (mostly play in winters) and other minor local sports. with growing facilities and particular local geography Climbing, trekking and other similar sports are also getting popularity. Samina Baig from Hunza valley is the only Pakistani woman and the third Pakistani to climb Mount Everest and also the youngest Muslim woman to climb Everest, having done so at the age of 21 while Hassan Sadpara from Skardu valley is the first Pakistani to have climbed six eight-thousanders including the world's highest peak Everest (8848m) besides K2 (8611m), Gasherbrum I (8080m), Gasherbrum II (8034m), Nanga Parbat (8126 m), Broad Peak (8051m).

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

_(claims_hatched).svg.png)

.jpg)