| HEPHTHALITES

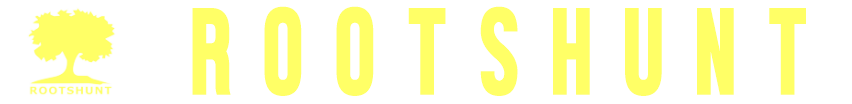

Tamga of the Imperial Hephthalites

The Hephthalites c. 500 CE Hephthalites

Empire

: 440s - 560

Capital : Kunduz (Walwalij, Drapsaka, or Badian) and Balkh (Pakhlo)

Common languages : Bactrian (official), Gandhari (Gandhar), Sogdian (Sogdiana), Chorasmian, Sanskrit and Turkic

Religion : Buddhism, Manichaeism, Zoroastrianism and Nestorian Christianity

Historical era : Late Antiquity

• Established : Empire: 440s

• Disestablished : 560 Principalities until 710

Preceded by

Kidarites

Sassanid Empire

Kangju

Alchon Huns

Succeeded by

Nezak Huns

First Turkic Khaganate

Turk Shahis

Zunbils

Principality of Chaghaniyan

The Hephthalites (Bactrian: Ebodalo, Arabic: al-Hayatila), sometimes called the White Huns, were a people who lived in Central Asia during the 5th to 8th centuries. They existed as an Empire, the Imperial Hephthalites, and were militarily important from 450 CE, when they defeated the Kidarites, to 560 CE, date of their defeat to combined First Turkic Khaganate and Sasanian Empire forces. After 560 CE, they formed "principalities" in the area of Tokharistan, under the suzerainty of the Western Turks (in the areas north of the Oxus) and the Sasanian Empire (in the areas south of the Oxus), before being taken over by the Tokhara Yabghus in 625 CE.

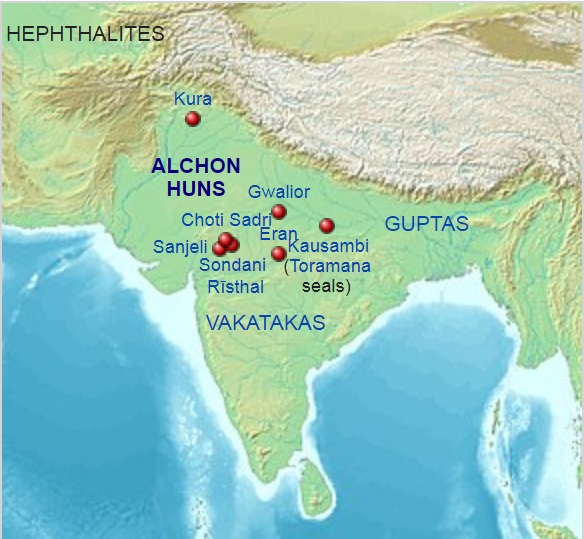

The Imperial Hephthalites were based in Bactria and expanded east to the Tarim Basin, west to Sogdia and south through Afghanistan, but they never went beyond the Hindu-Kush, which was occupied by the Alchon Huns, previously mistakenly considered as an extension of the Hephthalites. They were a tribal confederation and included both nomadic and settled urban communities.

They were part of the four major states known collectively as Xyon (Xionites) or Hun, being preceded by the Kidarites, and the Alkhon, and succeeded by the Nezak Huns and the First Turkic Khaganate. All of these Hunnic peoples have often been linked to the Huns who invaded Eastern Europe during the same period, and/or have been referred to as "Huns", but there is no consensus among scholars about such a connection.

The stronghold of the Hephthalites was Tokharistan on the northern slopes of the Hindu Kush, in what is present-day southern Uzbekistan and northern Afghanistan, and their capital was probably at Kunduz, having come from the east, possibly from the area of Badakshan. By 479, the Hephthalites had conquered Sogdia and driven the Kidarites eastwards, and by 493 they had captured parts of present-day Dzungaria and the Tarim Basin in what is now Northwest China. The Alchon Huns, formerly confused with the Hephthalites, expanded into Northern India as well.

The sources for Hephthalite history are poor and historians' opinions differ. There is no king-list and historians are not sure how they arose or what language they spoke. The Svet Hun who invaded Pakistan are probably the Hephthalites, but the exact relation is not clear. They seem to have called themselves Ebodalo (hence Hephthal), often abbreviated Eb, a name they wrote in the Bactrian script on some of their coins. The origin of the name "Hephthalites" is unknown, possibly from either a Khotanese word *Hitala meaning "Strong" or from postulated Middle Persian *haft al "the Seven".

Name and ethnonyms :

Hephthalite ruler

The Hephthalites called themselves ebodal as seen in a seal of a

Hephthalite king with the Bactrian script inscription ("The

Lord (Yabghu) of the Hephthalites"). End 5th century- early

6th century CE.

The name Hephthalites appears in Byzantine Greek sources, which also referred to them as Ephthalite, Abdel or Avdel.

To the Armenians, the Hephthalites were Haital, to the Persians and Arabs, they were Haytal or Hayatila, while their Bactrian name was Ebodalo.

In Chinese chronicles, the Hephthalites are called Ye-tha-i-li-to (pinyin: Yàndàiyílìtuó), or the more usual abbreviated form Yada (pinyin: Yèda), or (pinyin: Huá). The latter name has been given various Latinised renderings, including Yeda, Ye-ta, Ye-tha; Ye-da and Yanda. The corresponding Cantonese and Korean names Yipdaat and Yeoptal, which preserve aspects of the Middle Chinese pronunciation (roughly yep-daht) better than the modern Mandarin pronunciation, are more consistent with the Greek Hephthalite. Some Chinese chroniclers suggest that the root Hephtha- (as in Ye-ta-i-li-to or Yada) was technically a title equivalent to "emperor", while Hua was the name of the dominant tribe.

In Ancient India, names such as Hephthalite were unknown. The Hephthalites were apparently part of, or offshoots of, people known in India as Huns or Turushkas, although these names may have referred to broader groups or neighbouring peoples. Ancient Sanskrit text Pravishyasutra mentions a group of people named Havitaras but it is unclear whether the term denotes Hephthalites. The Indians also used the expression "White Huns" (Svet Hun) for the Hephthalites.

Geographical origin and expansion :

The Hephthalites came from Badakshan or the Altai, and always had their historical stronghold in Bactria (Tokharistan), with their capital in Kunduz According to recent scholarship, the stronghold of the Hephthalites was always Tokharistan on the northern slopes of the Hindu Kush, in what is present-day southern Uzbekistan and northern Afghanistan. Their capital was probably at Kunduz, which was known to the Al-Biruni as War-Waliz, a possible origin of one of the names given by the Chinese to Hephthalites: Hua (pinyin: Huá).

The Hephthalites may have came from the East, through the Pamir Mountains, possibly from the area of Badakshan. Alternatively, they may have migrated from the Altai region, among the waves of invading Huns.

Following their westward or southward expansion, the Hephthalites settled in Bactria, and displaced the Alchon Huns, who expanded into Northern India. The Hephthalites came into contact with the Sasanian Empire, and were involved in helping militarily Peroz I seize the throne from his brother Hormizd III.

Later, in the late 5th century, the Hephthalites expanded into vast areas of Central Asia, and occupied the Tarim Basin as far as Turfan, taking control of the area from the Ruanruans, who had been collecting heavy tribute from the oasis cities, but were now weakening under the assaults of the Chinese Wei Dynasty.

Characteristics :

There are several theories regarding the origins of the Hephthalites, with the Iranian, or Altaic theories being the most prominent.

According to most specialist scholars, the Hephthalites adopted Bactrian as their official language, just as the Kushans had done, following their settlement in Bactria / Tokharistan. Bactrian was an Eastern Iranian language, but was written in the Greek alphabet, a remnant of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom in the 3rd–2nd century BCE. The Bactrian, beyond being an official language, was also the language of the local populations ruled by the Hephthalites.

The Hephthalites inscribed their coins in Bactrian, an Iranian language written in the Greek script, the titles they held were Bactrian, such as XOAHO or Šao, and of probable Chinese origin, such as Yabghu, the names of Hephthalite rulers given in Ferdowsi's Shahnameh are Iranian, and gem inscriptions and other evidence shows that the official language of the Hephthalite elite was East Iranian. In 1959, Kazuo Enoki proposed that the Hephthalites were probably Indo-European (East) Iranians as some sources indicated that they were originally from Bactria, which is known to have been inhabited by Indo-Iranian people in antiquity. Richard Nelson Frye cautiously accepted Enoki's hypothesis, while at the same time stressing that the Hephthalites "were probably a mixed horde".

According to the Encyclopaedia Iranica and Encyclopaedia of Islam, the Hephthalites possibly originated in what is today Afghanistan. A few scholars, such as Marquart and Grousset proposed Proto-Mongolic origins. Yu Taishan traced the Hephthalites' origins to the Xianbei and further to Goguryeo. Other scholars such as de la Vaissière, based on a recent reappraisal of the Chinese sources, suggest that the Hephthalites were initially of Turkic origin, and later adopted the Bactrian language, first for administrative purposes, and possibly later as a native language; according to Rezakhani (2017), this thesis is seemingly the "most prominent at present".

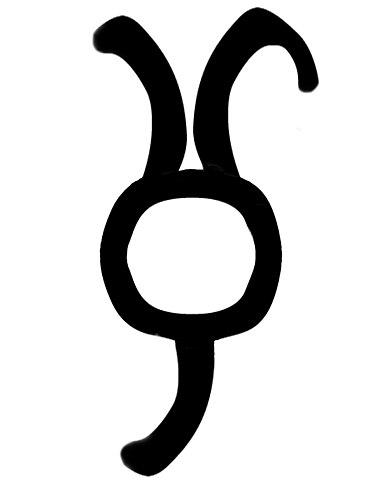

The banquet scenes in the murals of Balalyk Tepe show the life of the Hephthalite ruling class of Tokharistan In effect, the Hephthalites may have been a confederation of various people, speaking different languages. According to Richard Nelson Frye:

Just as later nomadic empires were confederations of many peoples, we may tentatively propose that the ruling groups of these invaders were, or at least included, Turkic-speaking tribesmen from the east and north, although most probably the bulk of the people in the confederation of Chionites and then Hephhtalites spoke an Iranian language. In this case, as normal, the nomads adopted the written language, institutions and culture of the settled folks.

Relation

to European Huns :

The 6th-century Byzantine historian Procopius of Caesarea (History of the Wars, Book I. ch. 3), related them to the Huns in Europe, but insisted on cultural and sociological differences, highlighting the sophistication of the Hephthalites :

The Ephthalitae Huns, who are called White Huns. The Ephthalitae are of the stock of the Huns in fact as well as in name, however they do not mingle with any of the Huns known to us, for they occupy a land neither adjoining nor even very near to them; but their territory lies immediately to the north of Persia. They are not nomads like the other Hunnic peoples, but for a long period have been established in a goodly land... They are the only ones among the Huns who have white bodies and countenances which are not ugly. It is also true that their manner of living is unlike that of their kinsmen, nor do they live a savage life as they do; but they are ruled by one king, and since they possess a lawful constitution, they observe right and justice in their dealings both with one another and with their neighbours, in no degree less than the Romans and the Persians.

Probable Hephthalite royal couple in the murals of the Buddhas of

Bamiyan circa 600 CE. Their characteristics are similar to the figures

in Balalyk Tepe, such as the right side triangular lapel, hairstyles,

faces and ornaments. The Bamiyan complex developed under Hephthalite

rule.

•

They were descendants

of the Jushi from Turfan;

The Hephthalite was a vassal state to the Rouran Khaganate until the beginning of the 5th century. Between Hephthalites and Rourans were also close contacts, although they had different languages and cultures, and Hephthalites borrowed much of their political organization from Rourans. In particular, the title "Khan", which according to McGovern was original to the Rourans, was borrowed by the Hephthalite rulers. The reason for the migration of the Hephthalites southeast was to avoid a pressure of the Rourans. Further, the Hephthalites defeated the "Smaller Yuezhi" (Kidarites) in Bactria in 460 CE, and their leader Kidara led them to the south into northwestern India.

Recent

reappraisal of Chinese sources :

Appearance :

Another painting of the Tokharistan school, from Tavka Kurgan. It is closely related to Balalyk tepe, "especially in the treatment of the face". Termez Archaeological Museum The Hepthalites appears in several mural paintings in the area of Tokharistan, especially in banquet scenes at Balalyk tepe and as donors to the Buddha in the ceiling painting of the 35 meter Buddha at the Buddhas of Bamiyan. Several of the figures in these paintings have a characteristic appearance, with belted jackets with a unique lapel of their tunic being folded on the right side, the cropped hair, the hair accessories, their distinctive physionomy and their round beardless faces. The figures at Bamiyan must represent the donors and potentates who supported the building of the monumental giant Buddh. These remarkable paintings participate "to the artistic tradition of the Hephthalite ruling classes of Tukharistan".

The paintings related to the Hephthalites have often been grouped under the appelation of "Tokharistan school of art", or the "Hephthalite stage in the History of Central Asia Art". The paintings of Tavka Kurgan, of very high quality, also belong to this school of art, and are closely related to other paintings of the Tokharistan school such as Balalyk tepe, in the depiction of clothes, and especially in the treatment of the faces.

This "Hephthalite period" in art, with the caftans with a triangular collar folded on the right, the particular cropped hairstyle, the crowns with crescents, have been found in many of the areas historically occupied and ruled by the Hephthalites, in Sogdia, Bamiyan (modern Afghanistan), or in Kucha in the Tarim Basin (modern Xinjiang, China). This points to a "political and cultural unification of Central Asia" with similar artistic styles and iconography, under the rule of the Hephthalites.

History

:

Around 466 they probably took Transoxianan lands from the Kidarites with Persian help but soon took from Persia the area of Balkh and eastern Kushanshahr. In the second half of the fifth century they controlled the deserts of Turkmenistan as far as the Caspian Sea and possibly Merv. By 500 they held the whole of Bactria and the Pamirs and parts of Afghanistan. In 509, they captured Sogdia and they took 'Sughd' (the capital of Sogdiana).

To the east, they captured the Tarim Basin and went as far as Urumqi.

Around 560 CE their empire was destroyed by an alliance of the First Turkic Khaganate and the Sasanian Empire, but some of them remained as local rulers in the region of Tokharistan for the next 150 years, under the suzerainty of the Western Turks, followed by the Tokhara Yabghus. Among the principalities which remained in Hephthalite hands even after the Turkic overcame their territory were: Chaganian, and Khuttal in the Vakhsh Valley.

Ascendancy over the Sasanian Empire (442 - c. 530 CE) :

Hephthalite coinage: a close imitation of a coin type of the Sasanian Emperor Peroz I (third period coinage of Peroz I, after 474 CE). Late 5th century CE. This coinage is typically distinguished from Sasanian issues by dots around the border and a more or less clear in front of the ruler, abbreviation of "EBODALO", for "Hepthalites".

Hephthalite coin with Sasanian-style bust imitating Khavadh I, whom the Hephthalites had helped to the Sasanian throne. Hephthalite tamgha Hephthalite tamgha.jpg before the face of the ruler. A Hephthalite prince holding a drinking cup appears on the reverse, with probable Bactrian legend "EBODALO" to the right.Late 5th century CE.

The Hephthalites were originally vassals of the Rouran Khaganate but split from their overlords in the early fifth century. The next time they were mentioned was in Persian sources as foes of Yazdegerd II (435–457), who from 442, fought 'tribes of the Hephthalites', according to the Armenian Elisee Vardaped.

In 453, Yazdegerd moved his court east to deal with the Hephthalites or related groups.

In 458, a Hephthalite king called Akhshunwar helped the Sasanian Emperor Peroz I (458–484) gain the Persian throne from his brother. Before his accession to the throne, Peroz had been the Sasanian for Sistan in the far east of the Empire, and therefore had been one of the first to enter into contact with the Hepthalites and request their help.

The Hephthalites may have also helped the Sasanians to eliminate another Hunnic tribe, the Kidarites: by 467, Peroz I, with Hephthalite aid, reportedly managed to capture Balaam and put an end to Kidarite rule in Transoxiana once and for all. The weakened Kidarites had to take refuge in the area of Gandhar.

Victories

over the Sasanian Empire (474 - 484 CE) :

In the third battle, at the Battle of Herat (484), he was killed, and for the next two years the Hephthalites plundered and controlled the eastern part of the Sasanian Empire. Perozduxt, the daughter of Peroz, was captured and became a lady as the Hephtalite court. She became pregnant, and had a daughter who would later marry her uncle Kavad I. From 474 until the middle of the 6th century, the Sasanian Empire paid tribute to the Hephthalites.

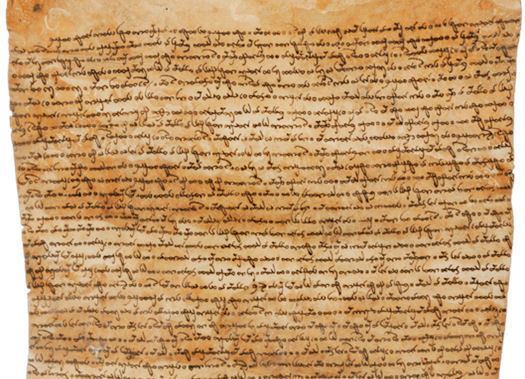

Bactria came under formal Hephthalite rule from that time. Taxes were levied by the Hephthalites over the local population: a contract in the Bactrian language from the archive of the Kingdom of Rob, has been found, which mentions taxes from the Hephthalites, requiring the sale of land in order to pay these taxes. It is dated to 483/484 CE.

With the Sasanian Empire paying tribute to the Hephthalites, from 474, the Hephthalites themselves adopted the winged, triple-crescent crowned Peroz I as the design for their coinage. Benefiting from the influx of Sasanian silver coins, the Hephthalites did not develop their own coinage: they either minted coins with the same designs as the Sasanians, or simply countermarked Sasanian coins with their own symbols. Exceptionally, one coin type deviates from the Sasanian design, by showing the bust of a Hepthalite prince holding a drinking cup. Overall, the Sasanians payed "an enormous tribute" to the Hephthalites, until the 530s and the rise of Khosrow I.

Protectors

of Kavad :

In 496–498, Kavadh I was overthrown by the nobles and clergy, escaped and restored himself with a Hephthalite army. Hephthalite troops helped Kavadh at a siege of Edessa.

Hephthalite conquest of Sogdiana (479 CE) :

Local coinage of Samarkand, Sogdia, with the Hepthalite tamgha on the reverse The Hephthalites may have conquered Sogdiana as early as 479 CE, as this is the date of the last known embassy of the Sogdians to China, or possibly a bit later around 509 CE, date of the last embassy from Samarkand. As early as 484, the name of the famous Hephthalite ruler Akhshunwar who defeated Peroz I may be understood as the Sogdian title "’xs’wnd’r" ("power-holder"). The Hepthalites conquered the territory of Sogdiana, beyond the Oxus, which was incorporated into their Empire. The Hepthalites may have built major fortified Hippodamian cities (rectangular walls with an orthogonal network of streets) in Sogdiana, such as Bukhara and Panjikent, as they had also in Herat, continuing the city-building efforts of the Kidarites. The wealth of the Sasanian ransoms and tributes may have been reinvested in Sogdia, possibly explaining the prosperity of the region from that time. Sogdia, at the center of a new Silk Road between China to the Sasanian Empire and the Byzantine Empire became extremely prosperous under its nomadic elites. The Hephthalites took on the role of major intermediary on the Silk Road, after their great predecessor the Kushans, and contracted local Sogdians to carry on the trade of silk and other luxury goods between the China Empire and the Sasanian Empire.

Because of the Hephthalite occupation of Sogdia, the original coinage of Sogdia came to be flooded by the influx Sasanian coins received as tribute to the Hephthalites. This coinage then spread along the Silk Road. The symbol of the Hephthalites appears on the residual coinage of Samarkand, probably as a consequence of the Hephthalite control of Sogdia, and becomes prominent in Sogdian coinage from 500 to 700 CE, ending with the Muslim conquest of Transoxiana.

Hephthalites in Tokharistan :

A tax receipt in Bactrian for the Hephthalites in Tokharistan, 483 / 484 CE Following the destruction of the Kidarites in 466, the Hepthalites probably expanded into the previous Kidarite territory of Tokharistan. The presence of the Hepthalites in Tokharistan (Bactria) is securely dated to 484 CE, date of a tax receipt from the Kingdom of Rob mentioning the need to sell some land in order to pay Hephthalite taxes.

Around this time, an Alchon Hun ruler named Mehama is know to have to have been based in Eastern Tokharistan, possibly indicating a partition of the region between the Hephthalites in western Tokharistan, centered on Balkh, and the Alchon Huns in eastern Tokharistan, who would then go on to expand into northern India.

Mehama appears in a letter in the Bactrian language he wrote in 461-462 CE, where he describes himself as "Meyam, King of the people of Kadag, the governor of the famous and prosperous King of Kings Peroz". Kadag is Kadagstan, an area in southern Bactria, in the region of Baghlan. Significantly, he presents himself as a vassal of the Sasanian Empire king Peroz I, but Mehama was probably later able to wrestle autonomy or even independence as Sasanian power waned and he moved into India, with dire consequences for the Gupta Empire.

Tarim Basin (circa 480 – 550 CE) :

Kizil Caves swordsmen in Hephthalite style. This mural was carbon dated to 432 – 538 CE

Painter in single-lapel caftan, Kizil Caves, circa 500 CE (enlarged detail). The label at his feet reads: "The Painter Tutuka" In the late 5th century CE they expanded eastward through the Pamir Mountains, which are comparatively easy to cross, as did the Kushans before them, due to the presence of convenient plateaus between high peaks. They occupied the western Tarim Basin (Kashgar and Khotan), taking control of the area from the Ruanruans, who had been collecting heavy tribute from the oasis cities, but were now weakening under the assaults of the Chinese Wei Dynasty. In 479 they took the east end of the Tarim Basin, around the region of Turfan. In 497–509, they pushed north of Turfan to the Urumchi region. In the early years of the 6th century, they were sending embassies from their dominions in the Tarim Basin to the Wei Dynasty. The Hephthalites continued to occupy the Tarim Basin until the end of their Empire, circa 560 CE.

As the territories ruled by the Hephthalites expanded into Central Asia and the Tarim Basin, the art of the Hephthalites, characterized by the clothing and hairstyles of the figures being represented, also came to be used in the areas they ruled, such as Sogdiana, Bamiyan or Kucha in the Tarim Basin (Kizil Caves, Kumtura Caves, Subashi reliquary). In these areas appear dignitaries with caftans with a triangular collar on the right side, crowns with three crescents, some crowns with wings, and a unique hairstyle. Another marker is the two-point suspension system for swords, which seems to have been an Hephthalite innovation, and was introduced by them in the territories they controled. The paintings from the Kucha region, particularly the swordmen in the Kizil Caves, appear to have been made during Hephthalite rule in the region, circa 480–550 CE. The influence of the art of Gandhara in some of the earliest paintings at the Kizil Caves, dated to circa 500 CE, is considered as a consequence of the political unification of the area between Bactria and Kucha under the Hephthalites.

The early Turks of the First Turkic Khaganate then took control of the Turfan and Kucha areas from around 560 CE, and, in alliance with the Sasanian Empire, became instrumental in the fall of the Hepthalite Empire.

End of the Imperial Hephthalites (560 CE) :

Hephthalite ambassadors (Baiti and Uar ethnicities) at the Chinese court of Emperor Yuan of Liang in his capital Jingzhou in 526 – 539 CE. Portraits of Periodical Offering of Liang, 11th century Song copy.

After Kavad I, the Hephthalites seem to have shifted their attention away from the Sasanian Empire, and Kavad's successor Khosrow I (531–579) was able to resume an expansionist policy to the east. In 552, the Göktürks took over Mongolia, formed the First Turkic Khaganate, and by 558 reached the Volga.

Circa 555–567, the Turks of the First Turkic Khaganate and the Sasanians under Khosrow I allied against the Hephthalites and defeated them after an eight-day battle near Qarshi, the Battle of Bukhara, perhaps in 557.These events put an end to the Hephthalite Kingdom. According to al-Tabari, Khosrow I had managed, through his expansionsit policy, to take control of "Sind, Bust, Al-Rukkhaj, Zabulistan, Tukharistan, Dardistan, and Kabulistan" as he ultimately defeated the Hephthalites with the help of the First Turkic Khaganate.

The allies then fought each other and c. 571 drew a border along the Oxus, with the north of the Oxus belonging to the Turks, and the south belonging to the Sasanians. After the battle, the Hephthalites withdrew to Bactria and replaced king Gatfar with Faghanish, the ruler of Chaghaniyan. Small Hephthalite principalities remained in the territory of today's Afghanistan, in the areas of Herat and Kabul. What happened in the Tarim Basin is not clear.

By 581 or before, the western part of the First Turkic Khaganate separated and became the Western Turkic Khaganate.

Raids

into the Sasanid Empire (7th century) :

The triple-crescent crown in this Penjikent mural (top left corner), is considered as a Hephthalite marker. 7th-early 8th century The area around the Oxus in Bactria contained numerous Hephthalites principalities, remnants of the great Hephthalite Empire destroyed by the alliance of the Turks and the Sasanians. They are reported in the Zarafshan valley, Chaghaniyan, Khuttal, Termez, Balkh, Badghis, Herat and Kabul.

From 625 CE, the territory of the Hephthalites was taken over by the Western Turks, forming the new entity of the Tokhara Yabghus. The Tokhara Yabghus or "Yabghus of Tokharistan" (Chinese: pinyin: Tuhuoluó Yèhù), were a dynasty of Western Turk sub-kings, with the title "Yabghus", who ruled from 625 CE south of the Oxus river, in the area of Tokharistan and beyond, with some smaller polities surviving in the area of Badakshan until 758 CE. Their legacy was extended to the southeast until the 9th century CE, with the Turk Shahis and the Zunbils.

Circa 651, during the Arab conquest, the ruler of Badghis was involved in the fall of the last Sassanian Shah Yazdegerd III. Circa 705, the Hephthalite rulers of Badghis and Chaghaniyan surrendered to the Arabs under Qutaiba ibn Muslim. Some remnants, not necessarily dynastic, of the Hephthalite confederation would be incorporated into the Göktürks, as an Old Tibetan document, dated to the 8th century, mentioned the tribe Heb-dal among 12 Dru-gu tribes ruled by Eastern Turkic khagan Bug-chor, i.e. Qapaghan Qaghan.

Religion and culture :

The

Buddhist "Hunter King" from Kakrak, a valley next to Bamiyan

is often presented as a result of Hephthalite influence, especially

in reference to the "triple-crescent crown". Wall paintings

from the 7th–8th century, Kabul Museum.

According to Song Yun, the Chinese Buddhist monk who visited the Hephthalite territory in 540 and "provides accurate accounts of the people, their clothing, the empresses and court procedures and traditions of the people and he states the Hephthalites did not recognize the Buddhist religion and they preached pseudo gods, and killed animals for their meat." It is reported that some Hephthalites often destroyed Buddhist monasteries but these were rebuilt by others. According to Xuanzang, the third Chinese pilgrim who visited the same areas as Song Yun about 100 years later, the capital of Chaghaniyan had five monasteries.

Buddhas of Bamiyan

Smaller 38 meter "Eastern" Buddha

Larger 55 meter "Western" Buddha

The Buddhas of Bamiyan, carbon-dated to 544-595 CE and 591-644 CE

respectively, were built under Hephthalite rule in the region. Murals

of probable Hephthalite rulers as royal sponsors appear in the paintings

of the ceiling over the smaller Buddha.

There were Christians among the Hephthalites by the mid-6th century, although nothing is known of how they were converted. In 549, they sent a delegation to Aba I, the patriarch of the Church of the East, asking him to consecrate a priest chosen by them as their bishop, which the patriarch did. The new bishop then performed obeisance to both the patriarch and the Sasanian king, Khosrow I. The seat of the bishopric is not known, but it may have been Badghis–Qadištan, the bishop of which, Gabriel, sent a delegate to the synod of Patriarch Ishoyahb I in 585. It was probably placed under the metropolitan of Herat. The church's presence among the Hephthalites enabled them to expand their missionary work across the Oxus. In 591, some Hephthalites serving in the army of the rebel Bahram Chobin were captured by Khosrow II and sent to the Roman emperor Maurice as a diplomatic gift. They had Nestorian crosses tattooed on their foreheads.

The Alchon Huns (formerly considered as Hephthalites) in South Asia :

Find spots of epigraphic inscriptions indicating local control by the Alchon Huns in India between 500 - 530 CE The Alchon Huns, who invaded northern India and were known there as "Huns", have long been considered as a part or a sub-division of the Hephthalites, or as their eastern branch, but now tend to be considered as a separate entity, who may have been displaced by the settlement of the Hephthalites in Bactria. Historians such as Beckwith, referring to Étienne de la Vaissière, say that the Hephthalites were not necessarily one and the same as the Huns (Svet Hun).

According to de la Vaissiere, the Hephthalites are not directly identified in classical sources alongside that of the Huns. They were initially based in the Oxus basin in Central Asia and established their control over Gandhar in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent by about 465 CE. From there, they fanned out into various parts of northern, western, and central India.

In India, these invading people were called Huns, or "Svet Hun" (White Huns) in Sanskrit. The Huns are mentioned in several ancient texts such as the Ramayan, Mahabharat, Purans, and Kalidas’s Raghuvansh. The first Huns, probably Kidarites, were initially defeated by Emperor Skandgupt of the Gupta Empire in the 5th century CE.

In the early 6th century CE, the Alchon Hun Huns in turn overran the part of the Gupta Empire that was to their southeast and had conquered Central and North India. Gupta Emperor Bhanugupt defeated the Huns under Toraman in 510, and his son Mihirkul was repulsed by Yashodharman in 528 CE. The Huns were driven out of India by the kings Yasodharman and Narasimhagupt, during the early 6th century.

Possible descendants :

Ambassador

from Chaganian visiting king Varkhuman of Samarkand 648–651

CE. Afrasiyab murals, Samarkand. Chaganian was an "Hephthalite

buffer principality" between Denov and Termez.

• Pashtuns : The Hephthalites may have contributed to the ethnogenesis of Pashtuns. Yu. V. Gankovsky, a Soviet historian on Afghanistan, stated: "Pashtun began as a union of largely East Iranian tribes, which became the initial ethnic stratum of the Pashtun ethnogenesis dating from the middle of the first millennium CE, and is connected with the dissolution of the Hephthalite confederacy."

• Khalaj

: The

Khalaj people are first mentioned in the 7th–9th centuries

in the area of Ghazni, Qalati Ghilji, and Zabulistan in present-day

Afghanistan. They spoke Khalaj Turkic. Al-Khwarizmi mentioned them

as a remnant tribe of the Hephthalites. However, according to linguist

Sims-Williams, archaeological documents do not support the suggestion

that the Khalaj were the Hephthalites' successors, while according

to historian V. Minorsky, the Khalaj were "perhaps only politically

associated with the Hephthalites." Some of the Khalaj were

later Pashtunized, after which they transformed into the Pashtun

Ghilji tribe.

• Rajputs : The Rajputs may have begun as assimilation of Hephthalites in Indian society.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

.jpg)

_of_the_Hephthalites._End_5th_century_early_6th_century_CE.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_5th-6th_cent_CE_Wall_Painting.jpg)

,_Hephthalite_tamgha_S2_on_the_reverse.jpg)

.jpg)

,_circa_500_CE.jpg)

__Eastern__Buddha_of_Bamiyan,_built_between_544_to_595_CE.jpg)