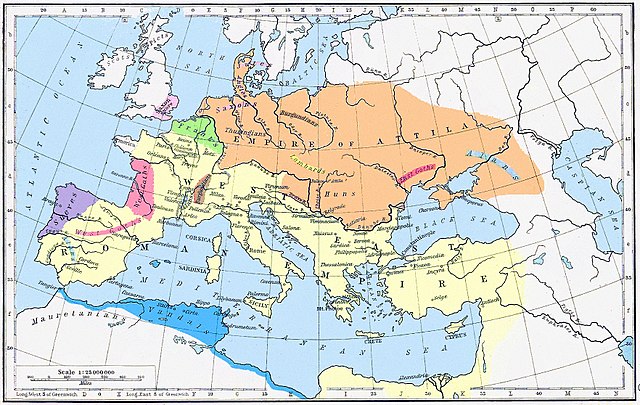

| HISTORY OF HUNS The history of the Huns spans the time from before their first secure recorded appearance in Europe around 370 AD to after the disintegration of their empire around 469. The Huns likely entered Europe shortly before 370 from Central Asia: they first conquered the Goths and the Alans, pushing a number of tribes to seek refuge within the Roman Empire. In the following years, the Huns conquered most of the Germanic and Scythian barbarian tribes outside of the borders of the Roman Empire. They also launched invasions of both the Asian provinces of Rome and the Sasanian Empire in 375. Under Uldin, the first Hunnic ruler named in contemporary sources, the Huns launched a first unsuccessful large-scale raid into the Eastern Roman Empire in Europe in 408. From the 420s, the Huns were led by the brothers Octar and Ruga, who both cooperated with and threatened the Romans. Upon Ruga's death in 435, his nephews Bleda and Attila became the new rulers of the Huns, and launched a successful raid into the Eastern Roman Empire before making peace and securing an annual tribute and trading raids under the Treaty of Margus. Attila appears to have killed his brother and became sole ruler of the Huns in 445. He would go on to rule for the next eight years, launching a devastating raid on the Eastern Roman Empire in 447, followed by an invasion of Gaul in 451. Attila is traditionally held to have been defeated in Gaul at the Battle of the Catalaunian Fields, however some scholars hold the battle to have been a draw or Hunnic victory. The following year, the Huns invaded Italy and encountered no serious resistance before turning back.

Hunnic dominion over Barbarian Europe is traditionally held to have collapsed suddenly after the death of Attila the year after the invasion of Italy. The Huns themselves are usually thought to have disappeared after the death of his son Dengizich in 469. However, some scholars have argued that the Bulgars in particular show a high degree of continuity with the Huns. Hyun Jin Kim has argued that the three major Germanic tribes to emerge from the Hunnic empire, the Gepids, the Ostrogoths, and the Scirii, were all heavily Hunnicized, and may have had Hunnic rather than native rulers even after the end of Hunnic dominion in Europe.

It is possible that the Huns were directly or indirectly responsible for the fall of the Western Roman Empire, and they have been directly or indirectly linked to the dominance of Turkic tribes on the Eurasian steppe following the fourth century.

Potential

history prior to 370 :

A tribe called the Ourougoúndoi (or Urugundi) who, according to Zosimus, invaded the Roman Empire from north of the Lower Danube in 250 AD may have been synonymous with the Bourougoundoi, whom Agathias (6th century) listed among the Hunnish tribes. Other scholars have regarded both names as referring to a Germanic tribe, the Burgundi (Burgundians), although this identification was rejected by Maenchen-Helfen (who speculated that one or both names may have approximated an early Turkic ethnonym, such as "Vurugundi").

Early

History :

A suggested path of the Huns' movement westwards (labels in German) The Huns' sudden appearance in the written sources suggests that the Huns crossed the Volga River from the east not much earlier. The reasons for the Huns' sudden attack on the neighboring peoples are unknown. One possible reason may have been climate change, however, Peter Heather notes that in the absence of reliable data this is unprovable. As a second possibility, Heather suggests some other nomadic group may have pushed them westward. Peter Golden suggests that the Huns may have been pushed west by the Jou-jan. A third possibility may have been a desire to increase their wealth by coming closer to the wealthy Roman Empire.

The Romans became aware of the Huns when the latter's invasion of the Pontic steppes forced thousands of Goths to move to the Lower Danube to seek refuge in the Roman Empire in 376, according to the contemporaneous Ammianus Marcellinus. There are also some indications that the Huns were already raiding Transcaucasia in the 360s and 370s. These raids eventually forced the Eastern Roman Empire and Sasanian Empire to jointly defend the passes through the Caucasus mountains.

Huns in battle with the Alans. An 1870s engraving after a drawing by Johann Nepomuk Geiger (1805 – 1880) The Huns first invaded the land of the Alans, which was located to the east of the Don River, defeating them and forcing the survivors to submit themselves to them or to flee across the Don. Maenchen-Helfen believes that rather than a direct conquest, the Huns instead allied themselves with groups of Alans. Writing much later, the historian Jordanes mentioned that the Huns also conquered "the Alpidzuri, the Alcildzuri, Itimari, Tuncarsi, and Boisci" in a battle by the Maeotian Swamp. These were potentially Turkic-speaking nomadic tribes who are later mentioned living under the Huns along the Danube.

Jordanes claimed that the Huns at this time were led by a king Balamber. E. A. Thompson doubts that such a figure ever existed, but argues that "they were operating [...] with a much larger force than any one of their tribes could have put to the field". Hyun Jin Kim argues that Jordanes has invented Balamber on the basis of the 5th century figure Valamer. However, Maenchen-Helfen credits that Balamber was a historic king, and Denis Sinor suggests that "Balamber was merely the leader of a tribe or an ad hoc group of warriors".

After they subjugated the Alans, the Huns and their Alan auxiliaries started plundering the wealthy settlements of the Greuthungi, or eastern Goths, to the west of the Don. Maenchen-Helfen suggests that it was as a result of their new alliance with these Alans that the Huns were able to threaten the Goths. The Greuthungic king, Ermanaric, resisted for a while, but finally "he found release from his fears by taking his own life", according to Ammianus Marcellinus. Marcellinus's report refers either to Ermanaric's suicide or to his ritual sacrifice. His great-nephew, Vithimiris, succeeded him. According to Ammianus, Vithimiris hired Huns to fight against the Alans who invaded the Greuthungi's land, but he was killed in a battle. Kim suggests that Ammianus has muddled events: the Alans, fleeing the Huns, likely attacked the Goths, who then called upon the Huns for aid. The Huns, having dealt with the Alans, "probably then in Machiavellian fashion fell upon the weakened Greuthungi Goths and conquered them as well".

Hun warriors. Colored engraving from 1890 After Vithimiris's death, most Greuthungi submitted themselves to the Huns: they retained their own king, named Hunimund, whose name means "protégé of the Huns". Those who decided to resist marched to the Dniester River which was the border between the lands of the Greuthungi and the Thervingi, or western Goths. They were under the command of Alatheus and Saphrax, because Vithimiris's son, Viderichus, was a child. Athanaric, the leader of the Thervingi, met the refugees along the Dniester at the head of his troops. However, a Hun army bypassed the Goths and attacked them from the rear, forcing Athanaric to retreat towards the Carpathian Mountains. Athanaric wanted to fortify the borders, but Hun raids into the land west of the Dniester continued.

Most Thervingi realized that they could not resist the Huns. They went to the Lower Danube, requesting asylum in the Roman Empire. The still resisting Greuthingi under the leadership of Alatheus and Saphrax also marched to the river. Most Roman troops had been transferred from the Balkan Peninsula to fight against the Sassanid Empire in Armenia. Emperor Valens permitted the Thervingi to cross the Lower Danube and to settle in the Roman Empire in the autumn of 376. The Thervingi were followed by the Greuthingi, and also by the Taifali and "other tribes that formerly dwelt with the Goths and Taifali" to the north of the Lower Danube, according to Zosimus. Food shortage and abuse stirred the Goths to revolt in early 377. The ensuing war between the Goths and the Romans lasted for more than five years.

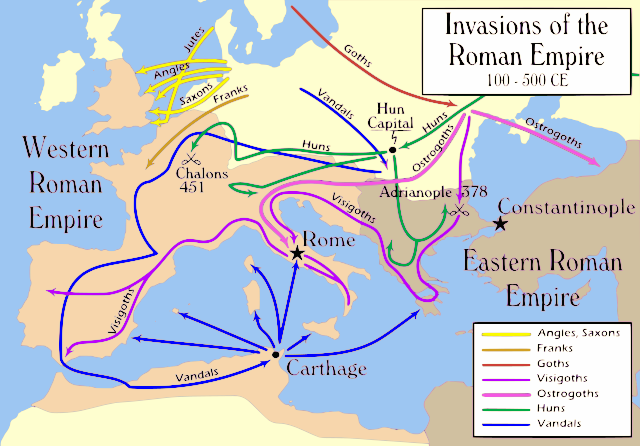

The Barbarian invasions of the 5th century were triggered by the destruction of the Gothic kingdoms by the Huns in 372–375. The city of Rome was captured and looted by the Visigoths in 410 and by the Vandals in 455.

First encounters with Rome :

Otto Maenchen-Helfen and E. A. Thompson argue that the Huns appear to have already been in possession of large parts of Pannonia (the Hungarian plain) as early as 384. Denis Sinor suggests that they may have been settled there are foederati of the Romans rather than as invaders, dating their presence to 380. In 384, the Roman-Frankish general Flavius Bauto employed Hunnic mercenaries to defeat the Juthungi tribe attacking from Rhaetia. However, the Huns, rather than return to their own country, began to ride to Gaul: Bauto was forced to bribe them to turn back. They then attacked the Alamanni.

Pacatus Drepanius reports that the Huns then fought with Theodosius against the usurper Magnus Maximus in 388. In 392, however, the Huns were again involved in raids in the Balkans, together with various other tribes. Some of the Huns seem to have settled in Thrace, and these Huns were then used as auxiliaries by Theodosius in 394; Maenchen-Helfen argues that the Romans may have hoped to use the Huns against the Goths. Kim believes that these mercenaries were not really Huns, but rather non-Hunnic groups capitalizing on the Huns' fearsome reputation as warriors. These Huns were eventually wiped up by the Romans in 401 after they began plundering the territory.

First

large scale attack on Rome and Persia :

Sinor argues that the much larger scale of the attacks on Asia Minor and Persia indicates that the bulk of the Huns had remained on the Pontic steppes rather than moving into Europe at this time. It seems clear that the Huns did not intend to conquer or settle the territories they attacked, but rather to plunder the provinces, taking, among other things, cattle. Priscus, writing much later, reports hearing from the Huns at Attila's camp that the raid was launched due to a famine on the steppes. This may also have been the reason for the raids into Thrace. Maenchen-Helfen suggests that Basich and Kursich, the Hun leaders responsible for the invasion of Persia, may have come to Rome in 404 or 407 as mercenaries: Priscus records that they came to Rome to make an alliance.

Hunnic attacks against Armenia would continue after this raid, with Armenian sources noting a Hunnic tribe known as the Xailandur as the perpetrators.

Uldin :

Campaigns of Uldin Uldin, the first Hun identified by name in contemporary sources, is identified as the leader of the Huns in Muntenia (modern Romania east of the Olt River) in 400. It is unclear how much territory or how many tribes of Huns Uldin actually controlled, although he clearly controlled parts of Hungary as well as Muntenia. The Romans referred to him as a regulus (sub-king): he himself boasted of immense power.

In 400, Gainas, rebellious former Roman magister militum fled into Uldin's territory with an army of Goths, and Uldin defeated and killed him, likely near Novae: he sent Gainas's head to Constantinople. Kim suggests that Uldin was interested in cooperating with the Romans while he expanded his control over Germanic tribes in the West. In 406, Hunnic pressure seems to have caused groups of Vandals, Suebi, and Alans to cross the Rhine into Gaul. Uldin's Huns raided Thrace in 404–405, likely in winter.

Also in 405, a group of Goths under Radagaisus invaded Italy, with Kim arguing that these Goths originated from Uldin's territory and that they were likely fleeing from some action of his. Stilicho, the Roman magister militum responded by asking for Uldin's aid: Uldin's Huns then destroyed Radagaisus's army near Faesulae in modern Tuscany in 406. Kim suggests Uldin acted in order to demonstrate his ability to destroy any groups of barbarians who might flee Hunnic rule. An army of 1000 of Uldin's Huns were also employed by the Eastern Roman Empire to fight against the Goths under Alaric. After Stilicho's death in 408, however, Uldin switched sides and began aiding Alaric under an army under the command of Alaric's brother-in-law Athaulf.

Also in 408, the Huns, under Uldin's command, crossed the Danube and captured the important fortress Castra Martis in Moesia. The Roman commander in Thrace attempted to make peace with Uldin, but Uldin refused his offers and demanded an extremely high tribute. However, many of Uldin's commanders subsequently defected to the Romans, bribed by the Romans. It appears that most of his army was actually composed by Scirii and Germanic tribes, whom the Romans subsequently sold into slavery. Uldin himself escaped back across the Danube, after which he is not mentioned again. The Romans responded to Uldin's invasions by attempting to strengthen the fortifications at the border, increasing the defenses at Constantinople, and taking other measures to strengthen their defences.

Hunnic mercenaries had also formed Stilicho's bodyguard: Kim suggests they were a gift from Uldin. The guard was either killed with Stilicho, or is the same as an elite unit of 300 Huns who continued to fight for the Romans against Alaric even after Uldin's invasion. During this same time, probably between 405 and 408, the future Roman magister militum and opponent of Attila Flavius Aetius was a hostage living among the Huns.

410s

:

Period

of unified Hunnic rule :

It is unclear when Ruga and his brother Octar became the supreme rulers of the Huns: Ruga appears to have ruled the land East of the Carpathians while Octar ruled the territory to the north and west of the Carpathians. Kim argues that Octar was a "deputy" king in his territory while Ruga was the supreme king. Octar died around 430 while fighting the Burgundians, who at the time lived on the right bank of the Rhine. Denis Sinor argues that his nephew Attila likely succeeded him as ruler of the eastern portion of the Huns' empire in this year. Maenchen-Helfen, however, argues that Ruga simply became sole ruler.

In 432, Ruga aided Aetius, who had fallen into disfavor, in reobtaining his old office of magister militum: Ruga either sent or threatened to send an army into Italy. In 433, Aetius surrendered Pannonia Prima to Ruga, perhaps as a reward for aid that Ruga's Huns had given him in securing his position. Either the previous year, in 432, or 434, Ruga sent an emissary to Constantinople announcing that he intended to attack some tribes whom he considered under his authority but who had fled into Roman territory; however, he died after the beginning of this campaign and the Huns left Roman territory.

Under Attila and Bleda :

A nineteenth century depiction of Attila. Certosa di Pavia – Medallion at the base of the facade. The Latin inscription tells that this is Attila, the scourge of God After Ruga's death, his nephews Attila and Bleda became the rulers of the Huns: Bleda appears to have ruled in the eastern portion of the empire, while Attila ruled the west. Kim believes that Bleda was the supreme king of the two. In 435, Bleda and Attila forced the Eastern Roman Empire to sign the Treaty of Margus, giving the Huns trade rights and increasing the annual tribute from the Romans. The Romans also agreed to hand over Hunnic refugees and fugitive tribes.

Ruga appears to have made a commitment to aid Aetius in Gaul before his death, and Attila and Bleda kept this commitment. In 437, Huns, under the direction of Aetius and possibly with the involvement of Attila, destroyed the Burgundian kingdom on the Rhine under king Gundahar, an event memorialized in medieval Germanic legend.It is possible that the Huns' destruction of the Burgundians was motivated by revenge for the death of Octar in 430. Also in 437, the Huns helped Aetius capture Tibatto, the leader of the Bagaudae, a group of rebellious peasants and slaves. In 438, an army of Huns aided the Roman general Litorius in an unsuccessful siege of the Visigothic capital of Toulouse. Priscus also mentions that the Huns extended their rule in "Scythia" and fought against an otherwise unknown people called the Sorosgi.

In 440, the Huns attacked the Romans during one of the annual trading fairs stipulated by the Treaty of Margus: the Huns justified this action by alleging that the bishop of Margus had crossed into Hunnic territory and plundered the Hunnic royal tombs and that the Romans themselves had breached the treaty by sheltering refugees from the Hunnic empire. When the Romans failed to turn over either the bishop of Margus or the refugees by 441, the Huns sacked a number of towns and captured the city of Viminacium, razing it to the ground. The bishop of Margus, terrified that he would be handed over to the Huns, made a deal to betray the city to the Huns, which was likewise razed. The Huns also captured the fortress of Constantia on the Danube, as well as capturing and razing the cities of Singidunum and Sirmium. After this the Huns agreed to a truce. Maenchen-Helfen supposes that their army may have been hit by a disease, or that a rival tribe may have attacked Hunnic territory, necessitating a withdrawal. Thompson dates a further large campaign against the Eastern Roman Empire to 443; however Maenchen-Helfen, Kim, and Heather date it to around 447, after Attila had become sole ruler of the Huns.

In 444, tensions rose between the Huns and the Western Empire, and the Romans made preparations for war; however, the tensions appear to have resolved the following year through the diplomacy of Cassiodorus. The terms seem to have involved the Romans handing over some territory to the Huns on the Sava River and may also have been when Attila was made magister militum to draw a salary.

Unified rule under Attila :

A map of Europe in 450 AD, showing the Hunnic Empire under Attila in orange, and the Roman Empire in yellow Bleda died some time between 442 and 447, with the most likely years being 444 or 445. He appears to have been murdered by Attila. Following Bleda's death, a tribe known as the Akatziri either rebelled against Attila or had never been under Attila's rule. Kim suggests that they rebelled specifically because of Bleda's death, as they were more likely to have been under Bleda's control than Attila's. The rebellion was actively encouraged by the Romans, who sent gifts to the Akatziri; however, the Romans offended the supreme chief, Buridach, by giving him gifts second rather than first. He subsequently appealed to Attila for help against the other rebellious leaders.Attila's forces then defeated the tribe after several battles: Buridach was allowed to rule his own tribe, but Attila placed his son Ellac in command of the remaining Akatziri.

Maenchen-Helfen argues that the Huns likely fought a war against the Longobards, living in modern Moravia, in 446, in which the Longobards successfully resisted Hunnic domination.

Some time after Bleda's death, while the Huns were busy with internal affairs, the Theodosius had ceased paying the stipulated tribute to the Huns. In 447, Attila sent an embassy to complain, threatening war and noting that his people were dissatisfied and that some had even begun raiding Roman territory. The Romans, however, refused to resume the tribute payments or hand over any refugees, and Attila began a full-scale attack by capturing the forts along the Danube. His forces included not only Huns, but also his subject peoples the Gepids, led by their king Ardaric, and the Goths under their king Valamer, as well as others. After they had cleared the Danube of Roman defences, the Huns then marched westward and defeated a large Roman army under the command of Arnegisclus at the Battle of the Utus. The Huns then sacked and razed Marcianople. The Huns then set out for Constantinople itself, whose walls had been partially destroyed by an earthquake earlier in the year. While the Constantinoplitans were able to rebuild the walls before Attila's army was able to approach, the Romans suffered another major defeat on the Gallipoli peninsula. The Huns proceeded to raid as far south as Thermopylae and captured most of the major towns in the Balkans except for Hadrianople and Heracleia. Theodosius was forced to sue for peace: in addition to the tribute the Romans had failed to pay before, the amount of yearly tribute was raised, and the Romans were forced to evacuate a large swath of territory south of the Danube to the Huns, thus leaving the border defenseless.

In 450, Attila negotiated a new treaty with the Romans and agreed to withdraw from Roman lands; Heather believes that this was in order for him to plan an invasion of the Western Roman Empire. According to Priscus, Attila contemplated an invasion of Persia at this time as well. The treaty with Constantinople was abrogated shortly afterward by the new emperor Marcian, however, Attila was already occupied with his plans for the Western Empire and did not respond.

Invasion of Gaul :

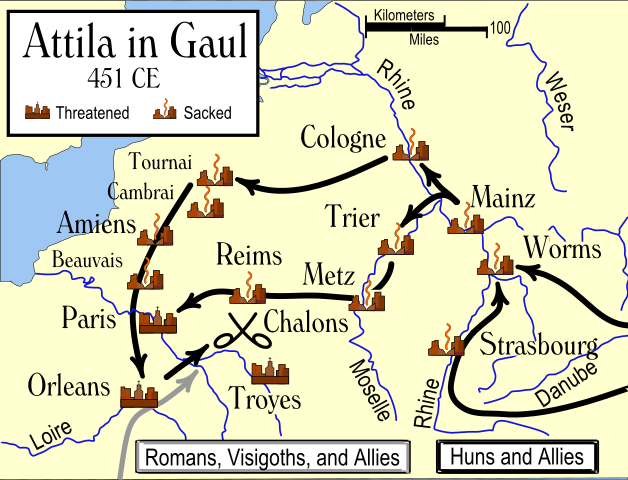

Attila in Gaul, 451 CE In spring of 451, Attila invaded Gaul. Relations with the Western Roman Empire appear to have deteriorated already by 449. One of the leaders of the Bagaudae, Eudoxius, had also fled to the Huns in 448. Aetius and Attila had also backed different candidates to be king of the Ripuarian Franks in 450. Attila claimed to the East Roman ambassadors in 450 that he intended to attack the Visigoths at Toulouse as an ally of the Western Emperor Valentinian III. According to one source, Honoria, the sister of Valentinian III, sent Attila a ring and asked for his aid in escaping imprisonment at the hands of her brother. Attila then demanded half of Western Roman territory as his dowry and invaded. Kim dismisses this story as of doubtful authenticity and a "ridiculous stor[y]". Heather is similarly skeptical that Attila would invade for this reason, noting that Attila invaded Gaul while Honoria was in Italy. Jordanes claims that Geiseric, king of the Vandals in North Africa, encouraged Attila to attack. Thompson suggests that Attila intended to remove Aetius and actually take up his honorary office as magister militum.Kim believes that it is unlikely that Attila actually intended to conquer Gaul, but rather to secure his control over Germanic tribes living on the Rhine.

The Hunnic army set out from the Hungarian Plain and likely crossed the Rhine near Koblenz. The Hunnic army included, besides Huns, the Gepids, Rugii, Sciri, Thuringi, Ostrogoths. Thompson suggests that Attila's first objection was the Ripuarian Franks, whom he summarily conquered and drafted into his army. They then captured Metz and Trier, before heading to besiege Orléans, with another detachment unsuccessfully attacking Paris. The approach of Aetius' army, consisting of Romans and allies such as the Visigoths under their king Theodoric I, Burgundians, the Alans, and some Franks, forced the Huns to break the siege of Orléans. Somewhere near Troyes, the two armies met and fought in the Battle of the Catalaunian Fields. In the standard scholarly view of the battle, despite the death of Theodoric, Attila's army was defeated and forced to retreat from Gaul. Kim argues that the battle was actually a Hunnic victory: the Huns had already been leaving Gaul after a successful campaign and simply continued to do so after the battle.

Invasion of Italy :

Raphael's The Meeting between Leo the Great and Attila depicts Pope Leo I, escorted by Saint Peter and Saint Paul, meeting with the Hun emperor outside Rome Upon his return to Pannonia, Attila ordered the launching of raids into Illyricum to encourage the Eastern Roman Empire to resume its tribute. Rather than attacking the Eastern Empire, however, in 452 he invaded Italy. The precise reasons for this are unclear: the Chronicle of 452 claims that it was due to his anger at his defeat in Gaul the previous year. The Huns crossed the Julian Alps and then besieged the heavily defended city of Aquileia, eventually capturing and razing it after a long siege. They then entered the Po Valley, sacking Padua, Mantua, Vicentia, Verona, Brescia, and Bergamo, before besieging and capturing Milan. The Huns made no attempt to capture Ravenna, and were either stopped or did not try to take Rome. Aetius was unable to offer an meaningful resistance and his authority was greatly damaged. The Huns received a peace embassy led by Pope Leo I and in the end turned back. However, Heather argues that it was a combination of disease and an attack by Eastern Roman troops on the Hunnic homeland in Pannonia that led to the Huns' withdrawal. Kim argues that the attacks by the Eastern Romans are a fiction, as the Eastern Empire was in a worse state than the West. Kim believes that the campaign had been a success and that the Huns simply withdrew after acquiring enough booty to satisfy them.

After

Attila :

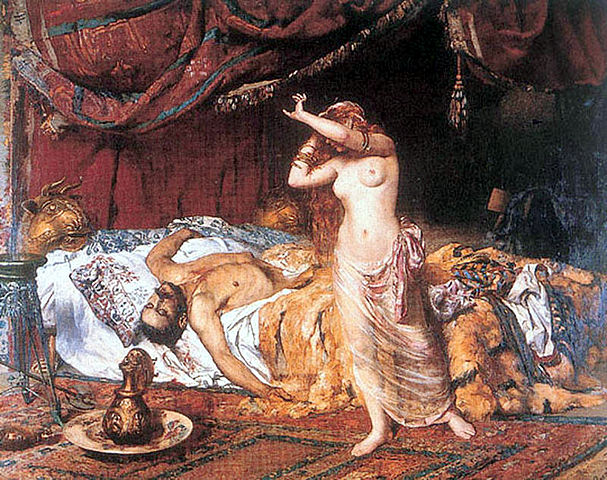

"The Death of Attila" by Ferenc Paczka In 453, Attila was reportedly planning a major campaign against the Eastern Romans to force them to resume paying tribute. However, he died unexpectedly, reportedly of a hemorrhage during his wedding to a new bride. He may also have been planning an invasion of the Sasanian Empire; Martin Schottky claims that "Attila’s death in 453 C.E. saved the Sasanians from an armed encounter with the Huns while they were at the height of their military power". Peter Heather, however, finds it unlikely that the Huns would have actually attacked Persia.

According to Jordanes, Attila's death precipitated a power struggle between his sons – it is unknown how many there were in total, but ancient sources mention three by name: Ellac, Dengizich and Ernak. The brothers began fighting one another, and this caused the Gepids under Ardaric to rebel. The Huns under Ellac then fought the Gepids and were defeated, resulting in Ellac's death. According to Jordanes, this occurred at the Battle of Nedao in 454, however, Heather speculates that there may have been more than just a single battle. Some tribes, such as the Scirii, fought on the Huns' side against the Gepids. He also notes that, while 454 may have been a significant turning point, it by no means ended Hunnic rule over most of their subject peoples. According to Heather, rather than an immediate collapse, the end of Hunnic rule was a slow process whereby the Huns gradually lost control over their subject peoples.

The Huns continued to exist under Attila's sons Dengizich and Ernak. Kim argues that Dengizich had successfully reestablished Hunnic rule over the western part of their empire in 464. In 466, Dengizich demanded that Constantinople resume paying tribute to the Huns and reestablish of the Huns' trading rights with the Romans. The Romans refused, however. Dengizich then decided to invade the Roman empire, with Ernak declining to join him to focus on other wars. Kim suggests that Ernak was distracted by the invasion of the Saragurs and other Oghurs, who had defeated the Akatziri in 463. Without his brother, Dengizich was forced to rely on the recently conquered Ostrogoths and the "unreliable" Bittigur tribe. His forces also included the Hunnic tribes of the Ultzinzures, Angiscires, and Bardores. The Romans were able to encourage the Goths in his army to revolt, forcing Dengizich to retreat. He died in 469, with Kim believing he was murdered, and his head was sent to the Romans. Anagastes, the son of Arnegisclus who was slain by Attila, brought Dengzich's head to Constantinople and paraded it through the streets before mounting it on a stake in the Hippodrome. This was the end of Hunnic rule in the West.

Germanic

tribes as successors to the Huns in the West :

The Scirii also emerged from Attila's empire with a potentially Hunnic King: Edeko is first encountered in sources as Attila's envoy, and is variously identified as having a Hunnic or Thuringian mother. While Heather believes that the latter is more likely, Kim argues that Edeco was in fact a Hun and that Thuringian in the source is a mistake for Torcilingi. Accordingly, his sons Hunoulph ("Hun-wolf") and Odoacer, who would go on to conquer Italy, would also be Huns ethnically, though the armies they led were certainly mostly Germanic. Odoacer would also conquer the Rogii, a tribe typically identified with the Rugii found in Tacitus' Germania, but whom Kim holds far more likely to be a newly formed tribe that was named after the Hunnic king Ruga.

The Goths led by the Amali dynasty under their king Valamir also became independent some time after 454. This did not include all Goths, however, some of whom are recorded as continuing to fight with the Huns as late as 468. Kim argues that even the Amali-led Goths remained loyal to the Huns until 459, when Valamir's nephew Theoderic was sent as a hostage to Constantinople, or even 461, when Valimir made an alliance with the Romans.Heather argues that the Amali united various groups of Goths sometime after Attila's death, though Jordanes claims that he did it while Attila was still alive. As he has for Ardaric and Ediko, Kim argues that Valimir, who is first attested as a confidant of Attila, was actually a Hun. Around 464, Valamir's Goths fought the Scirii, resulting in Valamir's death – this in turn caused the Goths to virtually destroy the Scirii. Dengizich then intervened – Kim supposes that the Scirii appealed to him for help, and that they together defeated the Goths. In a battle dated by Jordanes to 465, but by Kim to 470 after the death of Dengizich, the Scirii led an alliance of various tribes, including the Suebi, Rogii, Gepids, and Sarmatians against the Goths at the Battle of Bolia. The Gothic victory confirmed their independence and the end of Hunnic rule in the West.

Therefore, despite the collapse of the Western Hunnic Empire, Kim argues that the most important Barbarian leaders in Europe after Attila were all themselves Huns or were closely associated with Attila's empire.

Potential

continuation of Hunnic rule in the East :

Ancient sources appear to indicate that not all Hunnic peoples were incorporated into Ernak's Bulgar state.Huns continue to appear as mercenaries and allies of both the Persians and Romans in the sixth century as well. The Hunnic Altziagiri tribes continued to inhabit the Crimea near Cherson. Jordanes mentions two groups descended from Dengizich's Huns living on Roman territory, the Fossatisii and Sacromontisi. Kim, however, argues that we can distinguish just four large tribal groupings of Huns after the death of Dengizich; he argues that these were likely all ruled by members of Attila's dynasty. These groups often fought each other, however, and Kim argues that this allowed the Avars to conquer them and "recreat[e] the old Hunnic Empire in its entirety". He argues that Avars themselves had Hunnic, but not European Hunnic, elements prior to their invasion.

The tribe of Sabirs is sometimes identified in Byzantine sources as Huns, and Denis Sinor argues that they may have contained some Hunnic elements as well. Kim, however, identifies them with the Xianbei.

A final possible survival of the Huns are the North Caucasian Huns, who lived in what is now Dagestan. It is unclear whether these Huns were ever under Attila's rule. Kim argues that they are a group of Huns who were separated from the main confederation by the intruding Sabirs. In 503 they raided Persia, and they are recorded raiding Armenia, Cappadocia, and Lycaonia in 515. The Romans hired mercenaries from this group, including a king named Askoum. At some point, the North Caucasian Huns became a vassal state of the Khazar Khaganate. They are recorded to have converted to Christianity in 681. The North Caucasian Huns are last attested in the seventh century, but Kim argues that they may have persisted within the Khazar empire.

Historical

impact :

Within Europe, the Huns are typically held responsible for the beginning of the Migration period, in which mostly Germanic tribes increasingly moved into the space of the late Roman Empire. Peter Heather has argued that Huns were thereby responsible for the eventual disintegration of the Western Roman Empire, while E. A. Thompson argued that the Huns accelerated Germanic incursions both before and after their own presence on the Roman frontier. Walter Pohl, meanwhile notes that "[w]hat the Huns had achieved was a massive transfer of resources from the Roman empire to the barbaricum". Due to his differing opinions on the organization of the Huns, Hyun Jin Kim argues that, rather than by causing migrations of Germanic peoples, the Huns were responsible for the destruction of the Western Roman Empire by the force of their armies and their efficient imperial administration, leading to a collapse of the Roman military.

Other scholars have seen the Huns as less important in the end of Rome. J. Otto Maenchen-Helfen described the Hun's under Attila as "for a few years more than a nuisance to the Romans, though at no time a real danger". Other scholars such as J. B. Bury have in fact argued that the Huns held the Germanic tribes back and thus gave the empire a few more years of life.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

.png)

_-_n._8227_-_Certosa_di_Pavia_-_Medaglione_sullo_zoccolo_della_facciata.jpg)