| HUNS The

Huns :

Territory under Hunnic control circa 450 AD Common

languages : Hunnic, Gothic and Various tribal languages

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part of Scythia at the time; the Huns' arrival is associated with the migration westward of an Iranian people, the Alans. By 370 AD, the Huns had arrived on the Volga, and by 430 the Huns had established a vast, if short-lived, dominion in Europe, conquering the Goths and many other Germanic peoples living outside of Roman borders, and causing many others to flee into Roman territory. The Huns, especially under their King Attila, made frequent and devastating raids into the Eastern Roman Empire. In 451, the Huns invaded the Western Roman province of Gaul, where they fought a combined army of Romans and Visigoths at the Battle of the Catalaunian Fields, and in 452 they invaded Italy. After Attila's death in 453, the Huns ceased to be a major threat to Rome and lost much of their empire following the Battle of Nedao (454?). Descendants of the Huns, or successors with similar names, are recorded by neighbouring populations to the south, east, and west as having occupied parts of Eastern Europe and Central Asia from about the 4th to 6th centuries. Variants of the Hun name are recorded in the Caucasus until the early 8th century.

In the 18th century, the French scholar Joseph de Guignes became the first to propose a link between the Huns and the Xiongnu people, who were northern neighbours of China in the 3rd century BC. Since Guignes' time, considerable scholarly effort has been devoted to investigating such a connection. The issue remains controversial. Their relationships to other peoples known collectively as the Iranian Huns are also disputed.

Very little is known about Hunnic culture and very few archaeological remains have been conclusively associated with the Huns. They are believed to have used bronze cauldrons and to have performed artificial cranial deformation. No description exists of the Hunnic religion of the time of Attila, but practices such as divination are attested, and the existence of shamans likely. It is also known that the Huns had a language of their own, however only three words and personal names attest to it. Economically, they are known to have practiced a form of nomadic pastoralism; as their contact with the Roman world grew, their economy became increasingly tied with Rome through tribute, raiding, and trade. They do not seem to have had a unified government when they entered Europe, but rather to have developed a unified tribal leadership in the course of their wars with the Romans. The Huns ruled over a variety of peoples who spoke various languages and some of whom maintained their own rulers. Their main military technique was mounted archery.

The Huns may have stimulated the Great Migration, a contributing factor in the collapse of the Western Roman Empire. The memory of the Huns also lived on in various Christian saints' lives, where the Huns play the roles of antagonists, as well as in Germanic heroic legend, where the Huns are variously antagonists or allies to the Germanic main figures. In Hungary, a legend developed based on medieval chronicles that the Hungarians, and the Székely ethnic group in particular, are descended from the Huns. However, mainstream scholarship dismisses a close connection between the Hungarians and Huns. Modern culture generally associates the Huns with extreme cruelty and barbarism.

Origin :

The origins of the Huns and their links to other steppe people remain uncertain: scholars generally agree that they originated in Central Asia but disagree on the specifics of their origins. Classical sources assert that they appeared in Europe suddenly around 370. Most typically, Roman writers' attempts to elucidate the origins of the Huns simply equated them with earlier steppe peoples. Roman writers also repeated a tale that the Huns had entered the domain of the Goths while they were pursuing a wild stag, or else one of their cows that had gotten loose, across the Kerch Strait into Crimea. Discovering the land good, they then attacked the Goths. Jordanes' Getica relates that the Goths held the Huns to be offspring of "unclean spirits" and Gothic witches.

Relation to the Xiongnu and other peoples called Huns :

Since Joseph de Guignes in the 18th century, modern historians have associated the Huns who appeared on the borders of Europe in the 4th century AD with the Xiongnu who had invaded China from the territory of present-day Mongolia between the 3rd century BC and the 2nd century AD. Due to the devastating defeat by the Chinese Han dynasty, the northern branch of the Xiongnu had retreated north-westward; their descendants may have migrated through Eurasia and consequently they may have some degree of cultural and genetic continuity with the Huns. Scholars also discussed the relationship between the Xiongnu, the Huns, and a number of people in central Asia who were also known as or came to be identified with the name "Hun" or "Iranian Huns". The most prominent of these were Chionites, the Kidarites, and the Hephthalites.

Otto J. Maenchen-Helfen was the first to challenge the traditional approach, based primarily on the study of written sources, and to emphasize the importance of archaeological research. Since Maenchen-Helfen's work, the identification of the Xiongnu as the Huns' ancestors has become controversial. Additionally, several scholars have questioned the identification of the "Iranian Huns" with the European Huns. Walter Pohl cautions that none of the great confederations of steppe warriors was ethnically homogenous, and the same name was used by different groups for reasons of prestige, or by outsiders to describe their lifestyle or geographic origin. [...] It is therefore futile to speculate about identity or blood relationships between H(s)iung-nu, Hephthalites, and Attila's Huns, for instance. All we can safely say is that the name Huns, in late antiquity, described prestigious ruling groups of steppe warriors.

Recent scholarship, particularly by Hyun Jin Kim and Etienne de la Vaissière, has revived the hypothesis that the Huns and the Xiongnu are one and the same. De la Vaissière argues that ancient Chinese and Indian sources used Xiongnu and Hun to translate each other, and that the various "Iranian Huns" were similarly identified with the Xiongnu. Kim believes that the term Hun was "not primarily an ethnic group, but a political category" and argues for a fundamental political and cultural continuity between the Xiongnu and the European Huns, as well as between the Xiongnu and the "Iranian Huns".

Name

and etymology :

The etymology of Hun is unclear. Various proposed etymologies generally assume at least that the names of the various Eurasian groups known as Huns are related. There have been a number of proposed Turkic etymologies, deriving the name variously from Turkic ön, öna (to grow), qun (glutton), kün, gün, a plural suffix "supposedly meaning 'people'", qun (force), and hün (ferocious). Otto Maenchen-Helfen dismisses all of these Turkic etymologies as "mere guesses". Maenchen-Helfen himself proposes an Iranian etymology, from a word akin to Avestan hunara (skill), hunaravant- (skillful), and suggests that it may originally have designated a rank rather than an ethnicity. Robert Werner has suggested an etymology from Tocharian ku (dog), suggesting based on the fact that the Chinese called the Xiongnu dogs that the dog was the totem animal of the Hunnic tribe. He also compares the name Massagetae, noting that the element saka in that name means dog. Others such as Harold Bailey, S. Parlato, and Jamsheed Choksy have argued that the name derives from an Iranian word akin to Avestan ?yaona, and was a generalized term meaning "hostiles, opponents". Christopher Atwood dismisses this possibility on phonological and chronological grounds. While not arriving at an etymology per se, Atwood derives the name from the Ongi River in Mongolia, which was pronounced the same or similar to the name Xiongnu, and suggests that it was originally a dynastic name rather than an ethnic name.

Physical

appearance :

Many scholars take these to be unflattering depictions of East Asian ("Mongoloid") racial characteristics. Maenchen-Helfen argues that, while many Huns had East Asian racial characteristics, they were unlikely to have looked as Asiatic as the Yakut or Tungus. He notes that archaeological finds of presumed Huns suggest that they were a racially mixed group containing only some individuals with East Asian features. Kim similarly cautions against seeing the Huns as a homogenous racial group, while still arguing that they were "partially or predominantly of Mongoloid extraction (at least initially)." Some archaeologists have argued that archaeological finds have failed to prove that the Huns had any "Mongoloid" features at all, and some scholars have argued that the Huns were predominantly "Caucasian" in appearance. Other archaeologists have argued that "Mongoloid" features are found primarily among members of the Hunnic aristocracy, which, however, also included Germanic leaders who were integrated into the Hun polity. Kim argues that the composition of the Huns became progressively more "Caucasian" during their time in Europe; he notes that by the Battle of Chalons (451), "the vast majority" of Attila's entourage and troops appears to have been of European origin, while Attila himself seems to have had East Asian features.

Genetics

:

Neparáczki et al. 2019 examined the remains of three males from three separate 5th century Hunnic cemeteries in the Pannonian Basin. They were found to be carrying the paternal haplogroups Q1a2, R1b1a1b1a1a1 and R1a1a1b2a2. In modern Europe, Q1a2 is rare and has its highest frequency among the Székelys. All of the Hunnic males studied were determined to have had brown eyes and black or brown hair, and to have been of mixed European and East Asian ancestry. The results were consistent with a Xiongnu origin of the Huns.

Keyser et al. 2020 found that the Xiongnu shared certain paternal and maternal haplotypes with the Huns, and suggested on this basis that the Huns were descended from Xiongnu, who they in turn suggested were descended from Scytho-Siberians.

However, these genetic results only confirm the Inner Asian origins of the Huns, not synonymity with the Xiongnu. The fact remains is that there is no political or cultural continuity between the two groups. The remnants of the northern Xiongnu were either annihilated by the Imperial Chinese or absorbed by the succeeding Xianbei by the turn of the first century CE.

History

:

A suggested path of the Huns' movement westwards (labels in German) The Romans became aware of the Huns when the latter's invasion of the Pontic steppes forced thousands of Goths to move to the Lower Danube to seek refuge in the Roman Empire in 376. The Huns conquered the Alans, most of the Greuthungi or Eastern Goths, and then most of the Thervingi or Western Goths, with many fleeing into the Roman Empire. In 395 the Huns began their first large-scale attack on the Eastern Roman Empire. Huns attacked in Thrace, overran Armenia, and pillaged Cappadocia. They entered parts of Syria, threatened Antioch, and passed through the province of Euphratesia. At the same time, the Huns invaded the Sasanian Empire. This invasion was initially successful, coming close to the capital of the empire at Ctesiphon; however, they were defeated badly during the Persian counterattack.

During their brief diversion from the Eastern Roman Empire, the Huns may have threatened tribes further west.Uldin, the first Hun identified by name in contemporary sources, headed a group of Huns and Alans fighting against Radagaisus in defense of Italy. Uldin was also known for defeating Gothic rebels giving trouble to the East Romans around the Danube and beheading the Goth Gainas around 400–401. The East Romans began to feel the pressure from Uldin's Huns again in 408. Uldin crossed the Danube and pillaged Thrace. The East Romans tried to buy Uldin off, but his sum was too high so they instead bought off Uldin's subordinates. This resulted in many desertions from Uldin's group of Huns. Uldin himself escaped back across the Danube, after which he is not mentioned again.

Hunnish mercenaries are mentioned on several occasions being employed by the East and West Romans, as well as the Goths, during the late 4th and 5th century. In 433 some parts of Pannonia were ceded to them by Flavius Aetius, the magister militum of the Western Roman Empire.

Under Attila :

A nineteenth century depiction of Attila. Certosa di Pavia – Medallion at the base of the facade. The Latin inscription tells that this is Attila, the scourge of God From 434 the brothers Attila and Bleda ruled the Huns together. Attila and Bleda were as ambitious as their uncle Rugila. In 435 they forced the Eastern Roman Empire to sign the Treaty of Margus, giving the Huns trade rights and an annual tribute from the Romans. When the Romans breached the treaty in 440, Attila and Bleda attacked Castra Constantias, a Roman fortress and marketplace on the banks of the Danube. War broke out between the Huns and Romans, and the Huns overcame a weak Roman army to raze the cities of Margus, Singidunum and Viminacium. Although a truce was concluded in 441, two years later Constantinople again failed to deliver the tribute and war resumed. In the following campaign, Hun armies approached Constantinople and sacked several cities before defeating the Romans at the Battle of Chersonesus. The Eastern Roman Emperor Theodosius II gave in to Hun demands and in autumn 443 signed the Peace of Anatolius with the two Hun kings. Bleda died in 445, and Attila became the sole ruler of the Huns.

In 447, Attila invaded the Balkans and Thrace. The war came to an end in 449 with an agreement in which the Romans agreed to pay Attila an annual tribute of 2100 pounds of gold. Throughout their raids on the Eastern Roman Empire, the Huns had maintained good relations with the Western Empire. However, Honoria, sister of the Western Roman Emperor Valentinian III, sent Attila a ring and requested his help to escape her betrothal to a senator. Attila claimed her as his bride and half the Western Roman Empire as dowry. Additionally, a dispute arose about the rightful heir to a king of the Salian Franks. In 451, Attila's forces entered Gaul. Once in Gaul, the Huns first attacked Metz, then his armies continued westwards, passing both Paris and Troyes to lay siege to Orléans. Flavius Aetius was given the duty of relieving Orléans by Emperor Valentinian III. A combined army of Roman and Visigoths then defeated the Huns at the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains.

Raphael's The Meeting between Leo the Great and Attila depicts Pope Leo I, escorted by Saint Peter and Saint Paul, meeting with the Hun emperor outside Rome The following year, Attila renewed his claims to Honoria and territory in the Western Roman Empire. Leading his army across the Alps and into Northern Italy, he sacked and razed a number of cities. Hoping to avoid the sack of Rome, Emperor Valentinian III sent three envoys, the high civilian officers Gennadius Avienus and Trigetius, as well as Pope Leo I, who met Attila at Mincio in the vicinity of Mantua, and obtained from him the promise that he would withdraw from Italy and negotiate peace with the emperor. The new Eastern Roman Emperor Marcian then halted tribute payments, resulting in Attila planning to attack Constantinople. However, in 453 he died of a haemorrhage on his wedding night.

After

Attila :

The western Huns under Dengizich experienced difficulties in 461, when they were defeated by Valamir in a war against the Sadages, a people allied with the Huns. His campaigning was also met with dissatisfaction from Ernak, ruler of the Akatziri Huns, who wanted to focus on the incoming Oghur speaking peoples. Dengzich attacked the Romans in 467, without the assistance of Ernak. He was surrounded by the Romans and besieged, and came to an agreement that they would surrender if they were given land and his starving forces given food. During the negotiations, a Hun in service of the Romans named Chelchel persuaded the enemy Goths to attack their Hun overlords. The Romans, under their General Aspar and with the help of his bucellarii, then attacked the quarreling Goths and Huns, defeating them. In 469, Dengizich was defeated and killed in Thrace.

After Dengizich's death, the Huns seem to have been absorbed by other ethnic groups such as the Bulgars.Kim, however, argues that the Huns continued under Ernak, becoming the Kutrigur and Utigur Hunno-Bulgars. This conclusion is still subject to some controversy. Some scholars also argue that another group identified in ancient sources as Huns, the North Caucasian Huns, were genuine Huns. The rulers of various post-Hunnic steppe peoples are known to have claimed descent from Attila in order to legitimize their right to the power, and various steppe peoples were also called "Huns" by Western and Byzantine sources from the fourth century onward.

Lifestyle

and economy :

[T]he term 'nomad', if it denotes a wandering group of people with no clear sense of territory, cannot be applied wholesale to the Huns. All the so-called 'nomads' of Eurasian steppe history were peoples whose territory/territories were usually clearly defined, who as pastoralists moved about in search of pasture, but within a fixed territorial space.

Maenchen-Helfen notes that pastoral nomads (or "seminomads") typically alternate between summer pastures and winter quarters: while the pastures may vary, the winter quarters always remained the same. This is, in fact, what Jordanes writes of the Hunnic Altziagiri tribe: they pastured near Cherson on the Crimea and then wintered further north, with Maenchen-Helfen holding the Syvash as a likely location. Ancient sources mention that the Huns' herds consisted of various animals, including cattle, horses, and goats; sheep, though unmentioned in ancient sources, "are more essential to the steppe nomad even than horses" and must have been a large part of their herds.Additionally, Maenchen-Helfen argues that the Huns may have kept small herds of Bactrian camels in the part of their territory in modern Romania and Ukraine, something attested for the Sarmatians.

Ammianus Marcellinus says that the majority of the Huns' diet came from the meat of these animals, with Maenchen-Helfen arguing, on the basis of what is known of other steppe nomads, that they likely mostly ate mutton, along with sheep's cheese and milk. They also "certainly" ate horse meat, drank mare's milk, and likely made cheese and kumis. In times of starvation, they may have boiled their horses' blood for food.

Ancient sources uniformly deny that the Huns practiced any sort of agriculture. Thompson, taking these accounts at their word, argues that "[w]ithout the assistance of the settled agricultural population at the edge of the steppe they could not have survived". He argues that the Huns were forced to supplement their diet by hunting and gathering. Maenchen-Helfen, however, notes that archaeological finds indicate that various steppe nomad populations did grow grain; in particular, he identifies a find at Kunya Uaz in Khwarezm on the Ob River of agriculture among a people who practiced artificial cranial deformation as evidence of Hunnic agriculture. Kim similarly argues that all steppe empires have possessed both pastoralist and sedentary populations, classifying the Huns as "agro-pastoralist".

Horses and transportation :

Huns by Rochegrosse 1910 (detail) As a nomadic people, the Huns spent a great deal of time riding horses: Ammianus claimed that the Huns "are almost glued to their horses", Zosimus claimed that they "live and sleep on their horses", and Sidonius claimed that "[s]carce had an infant learnt to stand without his mother's aid when a horse takes him on his back". They appear to have spent so much time riding that they walked clumsily, something observed in other nomadic groups. Roman sources characterize the Hunnic horses as ugly. It is not possible to determine the exact breed of horse the Huns used, despite relatively good Roman descriptions. Sinor believes that it was likely a breed of Mongolian pony.However, horse remains are absent from all identified Hun burials. Based on anthropological descriptions and archaeological finds of other nomadic horses, Maenchen-Helfen believes that they rode mostly geldings.

Besides horses, ancient sources mention that the Huns used wagons for transportation, which Maenchen-Helfen believes were primarily used to transport their tents, booty, and the old people, women, and children.

Economic

relations with the Romans :

Roman villa in Gaul sacked by the hordes of Attila the Hun Civilians and soldiers captured by the Huns might also be ransomed back, or else sold to Roman slave dealers as slaves. The Huns themselves, Maenchen-Helfen argued, had little use for slaves due to their nomadic pastoralist lifestyle. More recent scholarship, however, has demonstrated that pastoral nomadists are actually more likely to use slave labor than sedentary societies: the slaves would have been used to manage the Huns' herds of cattle, sheep, and goats. Priscus attests that slaves were used as domestic servants, but also that educated slaves were used by the Huns in positions of administration or even architects. Some slaves were even used as warriors.

The Huns also traded with the Romans. E. A. Thompson argued that this trade was very large scale, with the Huns trading horses, furs, meat, and slaves for Roman weapons, linen, and grain, and various other luxury goods. While Maenchen-Helfen concedes that the Huns traded their horses for what he considered to have been "a very considerable source of income in gold", he is otherwise skeptical of Thompson's argument. He notes that the Romans strictly regulated trade with the barbarians and that, according to Priscus, trade only occurred at a fair once a year. While he notes that smuggling also likely occurred, he argues that "the volume of both legal and illegal trade was apparently modest". He does note that wine and silk appear to have been imported into the Hunnic Empire in large quantities, however. Roman gold coins appear to have been in circulation as currency within the whole of the Hunnic Empire.

Connections

to the Silk Road and synchronism :

There is also a remarkable synchronism between, on the one hand, the campaigns of the Huns under Attila in Europe, leading to their defeat at the Catalaunian Plains in 451 AD, and, on the other hand, the conflicts between the Kidarite Huns and the Sasanian Empire and the Gupta Empire in Southern Asia. The Sasanian Empire temporarily lost to the Kidarites in 453 AD, falling into a tributary relationship, while the Gupta Empire repelled the Kidarites in 455 AD, under emperor Skandgupt. It is almost as if the imperialist empire and the east and west had combined their response to a simultaneous Hunnic threat across Eurasia. In the end, Europe succeeded in repelling the Huns, and their power there quickly vanished, but in the east, both the Sasanian Empire and the Gupta Empire were left much weakened.

Government

:

Ammianus said that the Huns of his day had no kings, but rather that each group of Huns instead had a group of leading men (primates) for times of war . E.A. Thompson supposes that even in war the leading men had little actual power. He further argues that they most likely did not acquire their position purely heriditarily. Heather, however, argues that Ammianus merely means that the Huns didn't have a single ruler; he notes that Olympiodorus mentions the Huns having several kings, with one being the "first of the kings". Ammianus also mentions that the Huns made their decisions in a general council (omnes in commune) while seated on horse back. He makes no mention of the Huns being organized into tribes, but Priscus and other writers do, naming some of them.

The first Hunnic ruler known by name is Uldin. Thompson takes Uldin's sudden disappearance after he was unsuccessful at war as a sign that the Hunnic kingship was "democratic" at this time rather than a permanent institution. Kim however argues that Uldin is actually a title and that he was likely merely a subking. Priscus calls Attila "king" or "emperor", but it is unknown what native title he was translating. With the exception of the sole rule of Attila, the Huns often had two rulers; Attila himself later appointed his son Ellac as co-king. Subject peoples of the Huns were led by their own kings.

Priscus also speaks of "picked men" or logades forming part of Attila's government, naming five of them.Some of the "picked men" seem to have been chosen because of birth, others for reasons of merit. Thompson argued that these "picked men" "were the hinge upon which the entire administration of the Hun empire turned": he argues for their existence in the government of Uldin, and that each had command over detachments of the Hunnic army and ruled over specific portions of the Hunnic empire, where they were responsible also for collecting tribute and provisions. Maenchen-Helfen, however, argues that the word logades denotes simply prominent individuals and not a fixed rank with fixed duties. Kim affirms the importance of the logades for Hunnic administration, but notes that there were differences of rank between them, and suggests that it was more likely lower ranking officials who gathered taxes and tribute. He suggests that various Roman defectors to the Huns may have worked in a sort of imperial bureaucracy.

Society

and culture :

A Hunnish cauldron

Detail of Hunnish gold and garnet bracelet, 5th century, Walters Art Museum

A Hunnish oval openwork fibula set with a carnelian and decorated with a geometric pattern of gold wire, 4th century, Walters Art Museum There are two sources for the material culture and art of the Huns: ancient descriptions and archaeology. Unfortunately, the nomadic nature of Hun society means that they have left very little in the archaeological record. Indeed, although a great amount of archaeological material has been unearthed since 1945, as of 2005 there were only 200 positively identified Hunnic burials producing Hunnic material culture. It can be difficult to distinguish Hunnic archaeological finds from those of the Sarmatians, as both peoples lived in close proximity and seem to have had very similar material cultures. Kim thus cautions that it is difficult to assign any artifact to the Huns ethnically. It is also possible that the Huns in Europe adopted the material culture of their Germanic subjects.Roman descriptions of the Huns, meanwhile, are often highly biased, stressing their supposed primitiveness.

Archaeological finds have produced a large number of cauldrons that have since the work of Paul Reinecke in 1896 been identified as having been produced by the Huns. Although typically described as "bronze cauldrons", the cauldrons are often made of copper, which is generally of poor quality. Maenchen-Helfen lists 19 known finds of Hunnish cauldrons from all over Central and Eastern Europe and Western Siberia. He argues from the state of the bronze castings that the Huns were not very good metalsmiths, and that it is likely that the cauldrons were cast in the same locations where they were found. They come in various shapes, and are sometimes found together with vessels of various other origins. Maenchen-Helfen argues that the cauldrons were cooking vessels for boiling meat, but that the fact that many are found deposited near water and were generally not buried with individuals may indicate a sacral usage as well. The cauldrons appear to derive from those used by the Xiongnu. Ammianus also reports that the Huns had iron swords. Thompson is skeptical that the Huns cast them themselves, but Maenchen-Helfen argues that "[t]he idea that the Hun horsemen fought their way to the walls of Constantinople and to the Marne with bartered and captured swords is absurd."

Both ancient sources and archaeological finds from graves confirm that the Huns wore elaborately decorated golden or gold-plated diadems. Maenchen-Helfen lists a total of six known Hunnish diadems. Hunnic women seem to have worn necklaces and bracelets of mostly imported beads of various materials as well. The later common early medieval practice of decorating jewelry and weapons with gemstones appears to have originated with the Huns. They are also known to have made small mirrors of an originally Chinese type, which often appear to have been intentionally broken when placed into a grave.

Archaeological finds indicate that the Huns wore gold plaques as ornaments on their clothing, as well as imported glass beads. Ammianus reports that they wore clothes made of linen or the furs of marmots and leggings of goatskin.

Ammianus reports that the Huns had no buildings, but in passing mentions that the Huns possessed tents and wagons. Maenchen-Helfen believes that the Huns likely had "tents of felt and sheepskin": Priscus once mentions Attila's tent, and Jordanes reports that Attila lay in state in a silk tent. However, by the middle of the fifth century, the Huns are also known to have also owned permanent wooden houses, which Maenchen-Helfen believes were built by their Gothic subjects.

Artificial cranial deformation :

Landesmuseum Württemberg deformed skull, early 6th century Allemannic culture Various archaeologists have argued that the Huns, or the nobility of the Huns, as well as Germanic tribes influenced by them, practiced artificial cranial deformation, the process of artificially lengthening the skulls of babies by binding them. The goal of this process was "to create a clear physical distinction between the nobility and the general populace". While Eric Crubézy has argued against a Hunnish origin for the spread of this practice, the majority of scholars hold the Huns responsible for the spread of this custom in Europe. The practice was not originally introduced to Europe by the Huns, however, but rather with the Alans, with whom the Huns were closely associated, and Sarmatians. It was also practiced by other peoples called Huns in Asia.

Languages

:

As to the Hunnic language itself, only three words are recorded in ancient sources as being "Hunnic," all of which appear to be from an Indo-European language. All other information on Hunnic is contained in personal names and tribal ethnonyms. On the basis of these names, scholars have proposed that Hunnic may have been a Turkic language, a language between Mongolic and Turkic, or a Yeniseian language. However, given the small corpus, many scholars hold the language to be unclassifiable.

Marriage

and the role of women :

Priscus also attests that the widow of Attila's brother Bleda was in command of a village that the Roman ambassadors rode through: her territory may have included a larger area. Thompson notes that other steppe peoples such as the Utigurs and the Sabirs, are known to have had female tribal leaders, and argues that the Huns probably held widows in high respect. Due to the pastoral nature of the Huns' economy, the women likely had a large degree of authority over the domestic household.

John Man argues that the Huns of Attila's time likely worshipped the sky and the steppe deity Tengri, who is also attested as having been worshipped by the Xiongnu. Maenchen-Helfen also suggests the possibility that the Huns of this period may have worshipped Tengri, but notes that the god is not attested in European records until the ninth century. Worship of Tengri under the name "T'angri Khan" is attested among the Caucasian Huns in the Armenian chronicle attributed to Movses Dasxuranci during the later seventh-century. Movses also records that the Caucasian Huns worshipped trees and burnt horses as sacrifices to Tengri, and that they "made sacrifices to fire and water and to certain gods of the roads, and to the moon and to all creatures considered in their eyes to be in some way remarkable." There is also some evidence for human sacrifice among the European Huns. Maenchen-Helfen argues that humans appear to have been sacrificed at Attila's funerary rite, recorded in Jordanes under the name strava. Priscus claims that the Huns sacrificed their prisoners "to victory" after they entered Scythia, but this is not otherwise attested as a Hunnic custom and may be fiction.

In addition to these pagan beliefs, there are numerous attestations of Huns converting to Christianity and receiving Christian missionaries. The missionary activities among the Huns of the Caucasas seem to have been particularly successful, resulting in the conversion of the Hunnish prince Alp Ilteber. Attila appears to have tolerated both Nicene and Arian Christianity among his subjects. However, a pastoral letter by Pope Leo the Great to the church of Aquileia indicates that Christian slaves taken from there by the Huns in 452 were forced to participate in Hunnic religious activities.

Warfare :

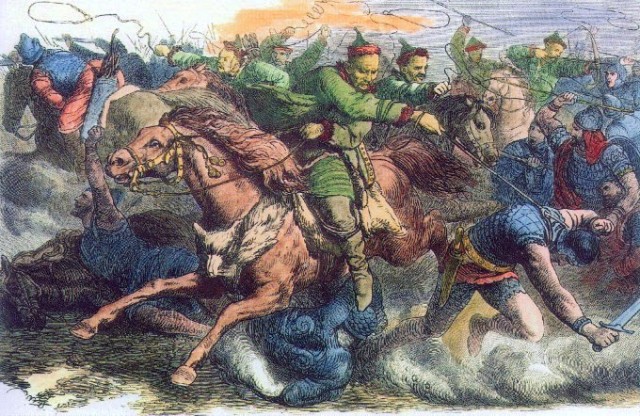

Huns in battle with the Alans. An 1870s engraving after a drawing by Johann Nepomuk Geiger (1805 – 1880)

Strategy and tactics :

They also sometimes fight when provoked, and then they enter the battle drawn up in wedge-shaped masses, while their medley of voices makes a savage noise. And as they are lightly equipped for swift motion, and unexpected in action, they purposely divide suddenly into scattered bands and attack, rushing about in disorder here and there, dealing terrific slaughter; and because of their extraordinary rapidity of movement they are never seen to attack a rampart or pillage an enemy's camp. And on this account you would not hesitate to call them the most terrible of all warriors, because they fight from a distance with missiles having sharp bone, instead of their usual points, joined to the shafts with wonderful skill; then they gallop over the intervening spaces and fight hand to hand with swords, regardless of their own lives; and while the enemy are guarding against wounds from the sabre-thrusts, they throw strips of cloth plaited into nooses over their opponents and so entangle them that they fetter their limbs and take from them the power of riding or walking.

Based on Ammianus' description, Maenchen-Helfen argues that the Huns' tactics did not differ markedly from those used by other nomadic horse archers. He argues that the "wedge-shaped masses" (cunei) mentioned by Ammianus were likely divisions organized by tribal clans and families, whose leaders may have been called a cur. This title would then have been inherited as it was passed down the clan. Like Ammianus, the sixth-century writer Zosimus also emphasizes the Huns' almost exclusive use of horse archers and their extreme swiftness and mobility. These qualities differed from other nomadic warriors in Europe at this time: the Sarmatians, for instance, relied on heavily armored cataphracts armed with lances. The Huns' use of terrible war cries are also found in other sources. However, a number of Ammianus's claims have been challenged by modern scholars. In particular, while Ammianus claims that the Huns knew no metalworking, Maenchen-Helfen argues that a people so primitive could never have been successful in war against the Romans.

Hunnic armies relied on their high mobility and "a shrewd sense of when to attack and when to withdraw". An important strategy used by the Huns was a feigned retreat-pretending to flee and then turning and attacking the disordered enemy. This is mentioned by the writers Zosimus and Agathias. They were, however, not always effective in pitched battle, suffering defeat at Toulouse in 439, barely winning at the Battle of the Utus in 447, likely losing or stalemating at the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains in 451, and losing at the Battle of Nedao (454?). Christopher Kelly argues that Attila sought to avoid "as far as possible, [...] large-scale engagement with the Roman army". War and the threat of war were frequently used tools to extort Rome; the Huns often relied on local traitors to avoid losses. Accounts of battles note that the Huns fortified their camps by using portable fences or creating a circle of wagons.

The Huns' nomadic lifestyle encouraged features such as excellent horsemanship, while the Huns trained for war by frequent hunting. Several scholars have suggested that the Huns had trouble maintaining their horse cavalry and nomadic lifestyle after settling on the Hungarian Plain, and that this in turn led to a marked decrease in their effectiveness as fighters.

The Huns are almost always noted as fighting alongside non-Hunnic, Germanic or Iranian subject peoples or, in earlier times, allies. As Heather notes, "the Huns' military machine increased, and increased very quickly, by incorporating ever larger numbers of the Germani of central and eastern Europe". At the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains, Attila is noted by Jordanes to have placed his subject peoples in the wings of the army, while the Huns held the center.

A major source of information on steppe warfare from the time of the Huns comes from the 6th-century Strategikon, which describes the warfare of "Dealing with the Scythians, that is, Avars, Turks, and others whose way of life resembles that of the Hunnish peoples." The Strategikon describes the Avars and Huns as devious and very experienced in military matters. They are described as preferring to defeat their enemies by deceit, surprise attacks, and cutting off supplies. The Huns brought large numbers of horses to use as replacements and to give the impression of a larger army on campaign. The Hunnish peoples did not set up an entrenched camp, but spread out across the grazing fields according to clan, and guard their necessary horses until they began forming the battle line under the cover of early morning. The Strategikon states the Huns also stationed sentries at significant distances and in constant contact with each other in order to prevent surprise attacks.

According to the Strategikon, the Huns did not form a battle line in the method that the Romans and Persians used, but in irregularly sized divisions in a single line, and keep a separate force nearby for ambushes and as a reserve. The Strategikon also states the Huns used deep formations with a dense and even front. The Strategikon states that the Huns kept their spare horses and baggage train to either side of the battle line at about a mile away, with a moderate sized guard, and would sometimes tie their spare horses together behind the main battle line. The Huns preferred to fight at long range, utilizing ambush, encirclement, and the feigned retreat. The Strategikon also makes note of the wedge shaped formations mentioned by Ammianus, and corroborated as familial regiments by Maenchen-Helfen. The Strategikon states the Huns preferred to pursue their enemies relentlessly after a victory and then wear them out by a long siege after defeat.

Peter Heather notes that the Huns were able to successfully besiege walled cities and fortresses in their campaign of 441: they were thus capable of building siege engines. Heather makes note of multiple possible routes for acquisition of this knowledge, suggesting that it could have been brought back from service under Aetius, acquired from captured Roman engineers, or developed through the need to pressure the wealthy silk road city states and carried over into Europe. David Nicolle agrees with the latter point, and even suggests they had a complete set of engineering knowledge including skills for constructing advanced fortifications, such as the fortress of Igdui-Kala in Kazakhstan.

Military

equipment :

A late Roman ridge helmet of the Berkasovo-Type was found with a Hun burial at Concesti. A Hunnic helmet of the Segmentehelm type was found at Chudjasky, a Hunnic Spangenhelm at Tarasovsky grave 1784, and another of the Bandhelm type at Turaevo. Fragments of lamellar helmets dating to the Hunnic period and within the Hunnic sphere have been found at Iatrus, Illichevka, and Kalkhni. Hun lamellar armour has not been found in Europe, although two fragments of likely Hun origin have been found on the Upper Ob and in West Kazakhstan dating to the 3rd–4th centuries. A find of lamellar dating to about 520 from the Toprachioi warehouse in the fortress of Halmyris near Badabag, Romania, suggests a late 5th or early 6th century introduction. It is known that the Eurasian Avars introduced lamellar armor to the Roman army and Migration-Era Germanic people in the mid 6th century, but this later type does not appear before then.

It is also widely accepted that the Huns introduced the langseax, a 60 cm cutting blade that became popular among the migration era Germanics and in the Late Roman army, into Europe. It is believed these blades originated in China and that the Sarmatians and Huns served as a transmission vector, using shorter seaxes in Central Asia that developed into the narrow langseax in Eastern Europe during the late 4th and first half of the 5th century. These earlier blades date as far back as the 1st century AD, with the first of the newer type appearing in Eastern Europe being the Wien-Simmerming example, dated to the late 4th century AD. Other notable Hun examples include the Langseax from the more recent find at Volnikovka in Russia.

The Huns used a type of spatha in the Iranic or Sassanid style, with a long, straight approximately 83 cm blade, usually with a diamond shaped iron guard plate. Swords of this style have been found at sites such as Altlussheim, Szirmabesenyo, Volnikovka, Novo-Ivanovka, and Tsibilium 61. They typically had gold foil hilts, gold sheet scabbards, and scabbard fittings decorated in the polychrome style. The sword was carried in the "Iranian style" attached to a swordbelt, rather than on a baldric.

The most famous weapon of the Huns is the Qum Darya-type composite recurve bow, often called the "Hunnish bow". This bow was invented some time in the 3rd or 2nd centuries BC with the earliest finds near Lake Baikal, but spread across Eurasia long before the Hunnic migration. These bows were typified by being asymmetric in cross-section between 145–155 cm in length, having between 4–9 lathes on the grip and in the siyahs. Although whole bows rarely survive in European climatic conditions, finds of bone Siyahs are quite common and characteristic of steppe burials. Complete specimens have been found at sites in the Tarim Basin and Gobi Desert such as Niya, Qum Darya, and Shombuuziin-Belchir. Eurasian nomads such as the Huns typically used trilobate diamond shaped iron arrowheads, attached using birch tar and a tang, with typically 75 cm shafts and fletching attached with tar and sinew whipping. Such trilobate arrowheads are believed to be more accurate and have better penetrating power or capacity to injure than flat arrowheads. Finds of bows and arrows in this style in Europe are limited but archaeologically evidenced. The most famous examples come from Wien-Simmerming, although more fragments have been found in the Northern Balkans and Carpathian regions.

Legacy

:

Martyrdom of Saint Ursula, by Hans Memling. The turbaned and armored figures represent Huns After the fall of the Hunnic Empire, various legends arose concerning the Huns. Among these are a number of Christian hagiographic legends in which the Huns play a role. In an anonymous medieval biography of Pope Leo I, Attila's march into Italy in 452 is stopped because, when he meets Leo outside Rome, the apostles Peter and Paul appear to him holding swords over his head and threatening to kill him unless he follows the pope's command to turn back. In other versions, Attila takes the pope hostage and is forced by the saints to release him. In the legend of Saint Ursula, Ursula and her 11,000 holy virgins arrive at Cologne on their way back from a pilgrimage just as the Huns, under an unnamed prince, are besieging the city. Ursula and her virgins are killed by the Huns with arrows after they refuse the Huns' sexual advances. Afterwards, the souls of the slaughtered virgins form a heavenly army that drives away the Huns and saves Cologne. Other cities with legends regarding the Huns and a saint include Orléans, Troyes, Dieuze, Metz, Modena, and Reims. In legends surrounding Saint Servatius of Tongeren dating to at least the eighth century, Servatius is said to have converted Attila and the Huns to Christianity, before they later became apostates and returned to their paganism.

In Germanic legend :

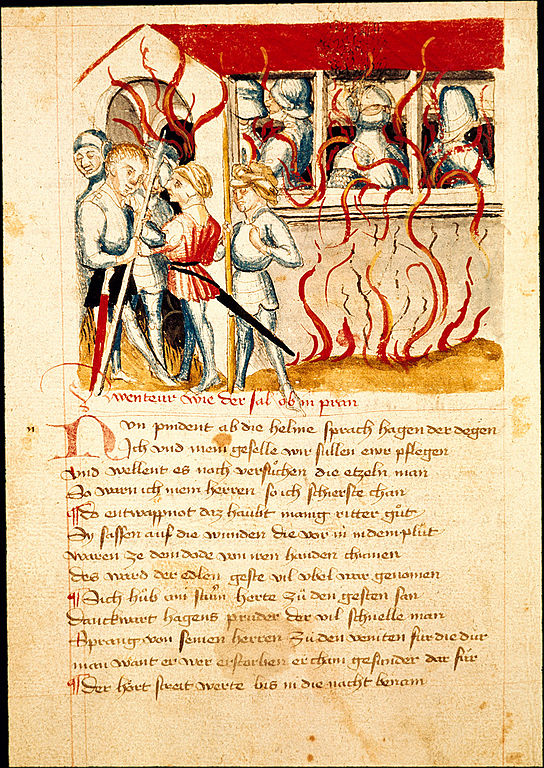

The Huns (outside) set fire to their own hall to kill the Burgundians. Illustration from the Hundeshagen Codex of the Nibelungenlied The Huns also play an important role in medieval Germanic legends, which frequently convey versions of events from the migration period and were originally transmitted orally. Memories of the conflicts between the Goths and Huns in Eastern Europe appear to be maintained in the Old English poem Widsith as well as in the Old Norse poem "The Battle of the Goths and Huns", which is transmitted in the thirteenth-century Icelandic Hervarar Saga. Widsith also mentions Attila having been ruler of the Huns, placing him at the head of a list of various legendary and historical rulers and peoples and marking the Huns as the most famous. The name Attila, rendered in Old English as Ætla, was a given name in use in Anglo-Saxon England (e.g. Bishop Ætla of Dorchester) and its use in England at the time may have been connected to the heroic kings legend represented in works such as Widsith. Maenchen-Helfen, however, doubts the use of the name by the Anglo-Saxons had anything to do with the Huns, arguing that it was "not a rare name." Bede, in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People, lists the Huns among other peoples living in Germany when the Anglo-Saxons invaded England. This may indicate that Bede viewed the Anglo-Saxons as descending partially from the Huns.

The Huns and Attila also form central figures in the two most-widespread Germanic legendary cycles, that of the Nibelungs and of Dietrich von Bern (the historical Theoderic the Great). The Nibelung legend, particularly as recorded in the Old Norse Poetic Edda and Völsunga saga, as well as in the German Nibelungenlied, connects the Huns and Attila (and in the Norse tradition, Attila's death) to the destruction of the Burgundian kingdom on the Rhine in 437. In the legends about Dietrich von Bern, Attila and the Huns provide Dietrich with a refuge and support after he has been driven from his kingdom at Verona. A version of the events of the Battle of Nadao may be preserved in a legend, transmitted in two differing versions in the Middle High German Rabenschlacht and Old Norse Thidrekssaga, in which the sons of Attila fall in battle. The legend of Walter of Aquitaine, meanwhile, shows the Huns to receive child hostages as tribute from their subject peoples. Generally, the continental Germanic traditions paint a more positive picture of Attila and the Huns than the Scandinavian sources, where the Huns appear in a distinctly negative light.

In medieval German legend, the Huns were identified with the Hungarians, with their capital of Etzelburg (Attila-city) being identified with Esztergom or Buda. The Old Norse Thidrekssaga, however, which is based on North German sources, locates Hunaland in northern Germany, with a capital at Soest in Westphalia. In other Old Norse sources, the term Hun is sometimes applied indiscriminately to various people, particularly from south of Scandinavia. From the thirteenth-century onward, the Middle High German word for Hun, hiune, became a synonym for giant, and continued to be used in this meaning in the forms Hüne and Heune into the modern era. In this way, various prehistoric megalithic structures, particularly in Northern Germany, came to be identified as Hünengräber (Hun graves) or Hünenbetten (Hun beds).

Links to the Hungarians :

Attila (right) as a king of Hungary together with Gyula and Béla I, Illustration for Il costume antico e moderno by Giulio Ferrario (1831)

Modern scholars largely dismiss these claims. Regarding the claimed Hunnish origins found in these chronicles, Jeno Szucs writes :

The Hunnish origin of the Magyars is, of course, a fiction, just like the Trojan origin of the French or any of the other origo gentis theories fabricated at much the same time. The Magyars in fact originated from the Ugrian branch of the Finno-Ugrian peoples; in the course of their wanderings in the steppes of Eastern Europe they assimilated a variety of (especially Iranian and different Turkic) cultural and ethnic elements, but they had neither genetic nor historical links to the Huns.

Generally, the proof of the relationship between the Hungarian and the Finno-Ugric languages in the nineteenth century is taken to have scientifically disproven the Hunnic origins of the Hungarians. Another claim, also derived from Simon of Kéza, is that the Hungarian-speaking Székely people of Transylvania are descended from Huns, who fled to Transylvania after Attila's death, and remained there until the Hungarian conquest of Pannonia. While the origins of the Székely are unclear, modern scholarship is skeptical that they are related to the Huns. László Makkai notes as well that some archaeologists and historians believe Székelys were a Hungarian tribe or an Onogur-Bulgar tribe drawn into the Carpathian Basin at the end of the 7th century by the Avars (who were identified with the Huns by contemporary Europeans). Unlike in the legend, the Székely were resettled in Transylvania from Western Hungary in the eleventh century. Their language similarly shows no evidence of a change from any non-Hungarian language to Hungarian, as one would expect if they were Huns. While the Hungarians and the Székelys may not be descendants of the Huns, they were historically closely associated with Turkic peoples. Pál Engel notes that it "cannot be wholly excluded" that Arpadian kings may have been descended from Attila, however, and believes that it is likely the Hungarians once lived under the rule of the Huns. Hyun Jin Kim supposes that the Hungarians might be linked to the Huns via the Bulgars and Avars, both of whom he holds to have had Hunnish elements.

While the notion that the Hungarians are descended from the Huns has been rejected by mainstream scholarship, the idea has continued to exert a relevant influence on Hungarian nationalism and national identity. A majority of the Hungarian aristocracy continued to ascribe to the Hunnic view into the early twentieth century. The Fascist Arrow Cross Party similarly referred to Hungary as Hunnia in its propaganda. Hunnic origins also played a large role in the ideology of the modern radical right-wing party Jobbik's ideology of Pan-Turanism. Legends concerning the Hunnic origins of the Székely minority in Romania, meanwhile, continue to play a large role in that group's ethnic identity. The Hunnish origin of the Székelys remains the most widespread theory of their origins among the Hungarian general public.

20th-century

use in reference to Germans :

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

_-_n._8227_-_Certosa_di_Pavia_-_Medaglione_sullo_zoccolo_della_facciata.jpg)

.jpg)