| IAZYGES

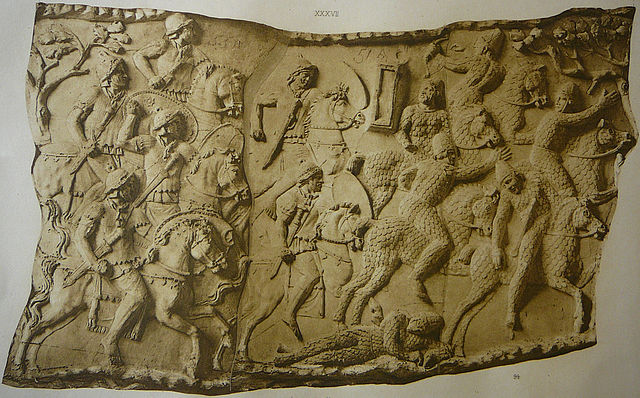

Sculpted image of a Sarmatian (an Iazyx would look similar) from the Casa degli Omenoni

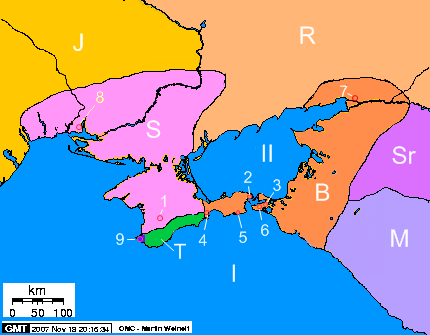

The Roman empire under Hadrian (ruled 117 – 138), showing the location of the Iazyges in the plain of the Tisza river

The Ninth European Map (in two parts) from a 15th - century Greek manuscript edition of Ptolemy's Geography, showing the Wandering Iazyges in the northwest between Pannonia and Dacia The Iazyges (were an ancient Sarmatian tribe that traveled westward in c. 200 BC from Central Asia to the steppes of what is now Ukraine. In c. 44 BC, they moved into modern-day Hungary and Serbia near the Dacian steppe between the Danube and Tisza rivers, where they adopted a semi-sedentary lifestyle.

In their early relationship with Rome, the Iazyges were used as a buffer state between the Romans and the Dacians; this relationship later developed into one of overlord and client state, with the Iazyges being nominally sovereign subjects of Rome. Throughout this relationship, the Iazyges carried out raids on Roman land, which often caused punitive expeditions to be made against them.

Almost all of the major events of the Iazyges, such as the two Dacian Wars—in both of which the Iazyges fought, assisting Rome in subjugating the Dacians in the first war and conquering them in the second—are connected with war. Another such war is the Marcomannic War that occurred between 169 and 175, in which the Iazyges fought against Rome but were defeated by Marcus Aurelius and had severe penalties imposed on them.

Culture

:

Etymology

:

According to Peter Edmund Laurent, a 19th-century French classical scholar, the Iazyges Metanastæ, a warlike Sarmatian race, which had migrated during the reign of the Roman Emperor Claudius, and therefore received the name of "Metanastæ", resided in the mountains west of the Theiss (Tisza) and east of the Gran (Hron) and Danube. The Greek Metanastæ means "migrants". The united Scythians and Sarmatæ called themselves Iazyges, which Laurent connected with Old Church Slavonic (jezyku, "tongue, language, people").

Burial

traditions :

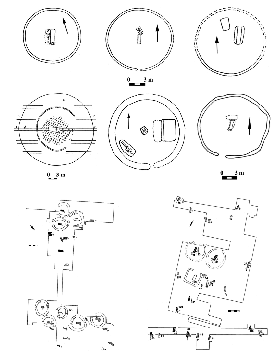

The graves made by the Iazyges were often rectangular or circular, although some were ovoid, hexagonal, or even octagonal. They were flat and were grouped like burials in modern cemeteries. Most of the graves' access openings face south, southeast, or southwest. The access openings are between 0.6 metres (2 ft 0 in) and 1.1 m (3 ft 7 in) wide. The graves themselves are between 5 m (16 ft) and 13 m (43 ft) in diameter.

After their migration to the Tisza plain, the Iazyges were in serious poverty. This is reflected in the poor furnishings found at burial sites, which are often filled with clay vessels, beads, and sometimes brooches. Iron daggers and swords were very rarely found in the burial site. Their brooches and arm-rings were of the La Tène type, showing the Dacians had a distinct influence on the Iazyges. Later tombs showed an increase in material wealth; tombs of the 2nd to early 4th century had weapons in them 86% of the time and armor in them 5% of the time. Iazygian tombs along the Roman border show a strong Roman influence.

Diet

:

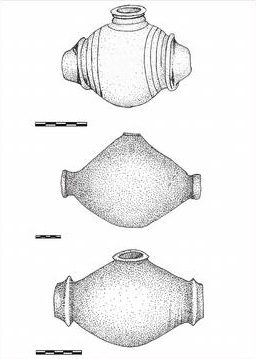

The Iazyges used hanging, asymmetrical, barrel-shaped pots that had uneven weight distribution. The rope used to hang the pot was wrapped around the edges of the side collar; it is believed the rope was tied tightly to the pot, allowing it to spin in circles. Due to the spinning motion, there are several theories about the pot's uses. It is believed the small hanging pots were used to ferment alcohol using the seeds of touch-me-not balsam (Impatiens noli-tangere), and larger hanging pots were used to churn butter and make cheese. The Iazyges were cattle breeders; they required salt to preserve their meat but there were no salt mines within their territory. According to Cassius Dio, the Iazyges received grain from the Romans.

Military

:

Religion

:

Economy

:

The Iazyges' trade with the Pontic Steppe and Black Sea was extremely important to their economy; after the Marcomannic War, Marcus Aurelius offered them the concession of movement through Dacia to trade with the Roxolani, which reconnected them with the Pontic Steppe trade network. This trade route lasted until 260, when the Goths took over Tyras and Olbia, cutting off both the Roxolani's and the Iazyges' trade with the Pontic Steppe. The Iazyges also traded with the Romans, although this trade was smaller in scale. While there are Roman bronze coins scattered along the entirety of the Roman Danubian Limes, the highest concentration of them appear in the Iazyges' territory.

Imports

:

The most commonly found imported ware was Terra sigillata. At Iazygian cemeteries, a single complete terra sigillata vessel and a large number of fragments have been found in Banat. Terra sigillata finds in Iazygian settlements are confusing in some cases; it can sometimes be impossible to determine the timeframe of the wares in relation to its area and thus impossible to determine whether the wares came to rest there during Roman times or after the Iazyges took control. Finds of terra sigillata of an uncertain age have been found in Deta, Kovacica–Capaš, Kuvin, Banatska Palanka, Pancevo, Vršac, Zrenjanin–Batka, Dolovo, Delibata, Perlez, Aradac, Botoš, and Bocar. Finds of terra sigillata that have been confirmed to having been made the time of Iazygian possession but of uncertain date have been found in Timisoara–Cioreni, Hodoni, Iecea Mica, Timisoara–Freidorf, Satchinez, Criciova, Becicherecul Mic, and Foeni–Seliste. The only finds of terra sigillata whose time of origin is certain have been found in Timisoara–Freidorf, dated to the 3rd century AD. Amphorae fragments have been found in Timisoara–Cioreni, Iecea Mica, Timisoara–Freidorf, Satchinez, and Biled; all of these are confirmed to be of Iazygian origin but none of them have definite chronologies.

In Tibiscum, an important Roman and later Iazygian settlement, only a very low percent of pottery imports were imported during or after the 3rd century. The pottery imports consisted of terra sigillata, amphorae, glazed pottery, and stamped white pottery. Only 7% of imported pottery was from the "late period" during or after the 3rd century, while the other 93% of finds were from the "early period", the 2nd century or earlier. Glazed pottery was almost nonexistent in Tibiscum; the only finds from the early period are a few fragments with Barbotine decorations and stamped with "CRISPIN(us)". The only finds from the late period are a handful of glazed bowl fragments that bore relief decorations on both the inside and the outside. The most common type of amphorae is the Dressel 24 similis; finds are from the time of rule of Hadrian to the late period. An amphora of type Carthage LRA 4 dated between the 3rd and 4th century AD has been found in Tibiscum-Iaz and an amphora of type Opait 2 has been found in Tibiscum-Jupa.

Geography

:

The area of plains between the Danube and Tisza rivers that was controlled by the Iazyges was similar in size to Italy and about 1,000 mi (1,600 km) long. The terrain was largely swampland dotted with a few small hills that was devoid of any mineable metals or minerals. This lack of resources and the problems the Romans would face trying to defend it may explain why the Romans never annexed it as a province but left it as a client-kingdom.

According to English cartographer Aaron Arrowsmith, Iazyges Metanastæ lived east (sic) of the [Roman] Dacia separating it from [Roman] Pannonia and Germania. Iazyges Metanastæ drove Daci from Pannonia and Tibiscus River (today known as Timi? River (or Tisza)).

History

:

In the 3rd century BC the Iazyges lived in modern-day south-eastern Ukraine along the northern shores of the Sea of Azov, which the Ancient Greeks and Romans called the Lake of Maeotis. From there, the Iazyges —or at least some of them —moved west along the shores of the Black Sea into modern-day Moldova and south-western Ukraine. It is possible the entirety of the Iazyges did not move west and that some of them stayed along the Sea of Azov, which would explain the occasional occurrence of the surname Metanastae; the Iazyges that possibly remained along the Sea of Azov, however, are never mentioned again.

Early

history :

Roman Balkans in the 1st century AD with the Jazyges Metanastæ between Roman Pannonia and Dacia

Map showing Iazyges in AD 125 west of Roman Dacia In the 2nd century BC, sometime before 179 BC, the Iazyges began to migrate westward to the steppe near the Lower Dniester. This may have occurred because the Roxolani, who were the Iazyges' eastern neighbors, were also migrating westward due to pressure from the Aorsi, which put pressure on the Iazyges and forced them to migrate westward as well.

The views of modern scholars as to how and when the Iazyges entered the Pannonian plain are divided. The main source of division is over the issue of if the Romans approved, or even ordered, the Iazyges to migrate, with both sides being subdivided into groups debating the timing of such a migration. Andreas Alföldi states that the Iazyges could not have been present to the north-east and east of the Pannonian Danube unless they had Roman approval. This viewpoint is supported by János Harmatta, who claims that the Iazyges were settled with both the approval and support of the Romans, so as to act as a buffer state against the Dacians.

András Mócsy suggests that Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Augur, who was Roman consul in 26 BC, may have been responsible for the settlement of the Iazyges as a buffer between Pannonia and Dacia. However, Mócsy also suggests that the Iazyges may have arrived gradually, such that they initially were not noticed by the Romans. John Wilkes believes that the Iazyges reached the Pannonian plain either by the end of Augustus's rule (14 AD) or some time between 17 and 20 AD. Constantin Daicoviciu suggests that the Iazyges entered the area around 20 AD, after the Romans called upon them to be a buffer state. Coriolan Opreanu supports the theory of the Iazyges being invited, or ordered, to occupy the Pannonian plain, also around 20 AD. Gheorghe Bichir and Ion Hora?iu Cri?an support the theory that the Iazyges first began to enter the Pannonian plain in large numbers under Tiberius, around 20 AD. The most prominent scholars that state the Iazyges were not brought in by the Romans, or later approved, are Doina Benea, Mark Šcukin, and Jeno Fitz. Doina Benea states that the Iazyges slowly infiltrated the Pannonian plain sometime in the first half of the 1st century AD, without Roman involvement. Jeno Fitz promotes the theory that the Iazyges arrived en masse around 50 AD, although a gradual infiltration preceded it. Mark Šcukin states only that the Iazyges arrived by themselves sometime around 50 AD. Andrea Vaday argued against the theory of a Roman approved or ordered migration, citing the lack of strategic reasoning, as the Dacians were not actively providing a threat to Rome during the 20–50 AD period.

The occupation of the lands between the Danube and Tisza by the Iazyges was mentioned by Pliny the Elder in his Naturalis Historia (77–79 AD), in which he says that the Iazyges inhabited the basins and plains of the lands, while the forested and mountainous area largely retained a Dacian population, which was later pushed back to the Tisza by the Iazyges. Pliny's statements are corroborated by the earlier accounts of Seneca the Younger in his Quaestiones Naturales (61–64 AD), where he uses the Iazyges to discuss the borders that separate the various peoples.

From 78 to 76 BC, the Romans led an expedition to an area north of the Danube —then the Iazyges' territory —–because the Iazyges had allied with Mithridates VI of Pontus, with whom the Romans were at war. In 44 BC King Burebista of Dacia died and his kingdom began to collapse. After this, the Iazyges began to take possession of the Pannonian Basin, the land between the Danube and Tisa rivers in modern-day south-central Hungary. Historians have posited this was done at the behest of the Romans, who sought to form a buffer state between their provinces and the Dacians to protect the Roman province of Pannonia. The Iazyges encountered the Basternae and Getae along their migration path sometime around 20 AD and turned southward to follow the coast of the Black Sea until they settled in the Danube Delta. This move is attested by the large discrepancy in the location reported by Tacitus relative to that which was earlier given by Ovid. Archeological finds suggest that while the Iazyges took hold of the northern plain between the Danube and the Tisa by around 50 AD, they did not take control of the land south of the Partiscum-Lugio line until the late 1st or early 2nd century.

The effects of this migration have been observed in the ruins of burial sites left behind by the Iazyges; the standard grave goods made of gold being buried alongside a person were absent, as was the equipment of a warrior; this may have been because the Iazyges were no longer in contact with the Pontic Steppe and were cut off from all trade with them, which had previously been a vital part of their economy. Another problem with the Iazyges' new location was that it lacked both precious minerals and metals, such as iron, which could be turned into weapons. They found it was much more difficult to raid the Romans, who had organized armies around the area, as opposed to the disorganized armies of their previous neighbors. The cutting-off of trade with the Pontic Steppe meant they could no longer trade for gold for burial sites, assuming any of them could afford it. The only such goods they could find were the pottery and metals of the adjacent Dacian and Celtic peoples. Iron weapons would have been exceedingly rare, if the Iazyges even had them, and would likely have been passed down from father to son rather than buried because they could not have been replaced.

During the time of Augustus, the Iazyges sent an embassy to Rome to request friendly relations. In a modern context, these "friendly relations" would be similar to a non-aggression pact. Later, during the reign of Tiberius, the Iazyges became one of many new client-tribes of Rome. Roman client states were treated according to the Roman tradition of patronage, exchanging rewards for service. The client king was called socius et amicus Romani Populi (ally and friend of the Roman People); the exact obligations and rewards of this relationship, however, are vague. Even after being made into a client state, the Iazyges conducted raids across their border with Rome, for example in 6 AD and again in 16 AD. In 20 AD the Iazyges moved westward along the Carpathians into the Pannonian Steppe, and settled in the steppes between the Danube and the Tisza river, taking absolute control of the territory from the Dacians. In 50 AD, an Iazyges cavalry detachment assisted King Vannius, a Roman client-king of the Quadi, in his fight against the Suevi.

In the Year of Four Emperors, 69 AD, the Iazyges gave their support to Vespasian, who went on to become the sole emperor of Rome. The Iazyges also offered to guard the Roman border with the Dacians to free up troops for Vespasian's invasion of Italy; Vespasian refused, however, fearing they would attempt a takeover or defect. Vespasian required the chiefs of the Iazyges to serve in his army so they could not organize an attack on the undefended area around the Danube. Vespasian enjoyed support from the majority of the Germanic and Dacian tribes.

Domitian's campaign against Dacia was mostly unsuccessful; the Romans, however, won a minor skirmish that allowed him to claim it as a victory, even though he paid the King of Dacia, Decebalus, an annual tribute of eight million sesterces in tribute to end the war. Domitian returned to Rome and received an ovation, but not a full triumph. Considering that Domitian had been given the title of Imperator for military victories 22 times, this was markedly restrained, suggesting the populace —–or at least the senate —was aware it had been a less-than-successful war, despite Domitian's claims otherwise. In 89 AD, however, Domitian invaded the Iazyges along with the Quadi and Marcomanni. Few details of this war are known but it is recorded that the Romans were defeated, it however known that Roman troops acted to repel simultaneous incursion by the Iazyges into Dacian lands.

In early 92 AD the Iazyges, Roxolani, Dacians, and Suebi invaded the Roman province of Pannonia —modern-day Croatia, northern Serbia, and western Hungary. Emperor Domitian called upon the Quadi and the Marcomanni to supply troops to the war. Both client-tribes refused to supply troops so Rome declared war upon them as well. In May 92 AD, the Iazyges annihilated the Roman Legio XXI Rapax in battle. Domitian, however, is said to have secured victory in this war by January of the next year. It is believed, based upon a rare Aureus coin showing an Iazyx with a Roman standard kneeling, with the caption of "Signis a Sarmatis Resitvtis", that the standard taken from the annihilated Legio XXI Rapax was returned to Rome at the end of the war. Although the accounts of the Roman-Iazyges wars of 89 and 92 AD are both muddled, it has been shown they are separate wars and not a continuation of the same war. The threat presented by the Iazyges and neighbouring people to the Roman provinces was significant enough that Emperor Trajan travelled across the Mid and Lower Danube in late 98 to early 99, where he inspected existing fortification and initiated the construction of more forts and roads.

Tacitus, a Roman Historian, records in his book Germania, which was written in 98 AD, that the Osi tribes paid tribute to both the Iazyges and the Quadi, although the exact date this relationship began is unknown. During the Flavian dynasty, the princes of the Iazyges were trained in the Roman army, officially as an honor but in reality serving as a hostage, because the kings held absolute power over the Iazyges. There were offers from the princes of the Iazyges to supply troops but these were denied because of the fear they might revolt or desert in a war.

Dacian

wars :

First

Dacian War :

Second

Dacian War :

After

the Dacian Wars :

Ownership of the region of Oltenia became a source of dispute between the Iazyges and the Roman empire. The Iazyges had originally occupied the area before the Dacians seized it; it was taken during the Second Dacian War by Trajan, who was determined to constitute Dacia as a province. The land offered a more direct connection between Moesia and the new Roman lands in Dacia, which may be the reason Trajan was determined to keep it. The dispute led to war in 107–108, where the future emperor Hadrian, then governor of Pannonia Inferior, defeated them. The exact terms of the peace treaty are not known, but it is believed the Romans kept Oltenia in exchange for some form of concession, likely involving a one-time tribute payment. The Iazyges also took possession of Banat around this time, which may have been part of the treaty.

In 117, the Iazyges and the Roxolani invaded Lower Pannonia and Lower Moesia, respectively. The war was probably brought on by difficulties in visiting and trading with each other because Dacia lay between them. The Dacian provincial governor Gaius Julius Quadratus Bassus was killed in the invasion. The Roxolani surrendered first, so it is likely the Romans exiled and then replaced their client king with one of their choosing. The Iazyges then concluded peace with Rome. The Iazyges and other Sarmatians invaded Roman Dacia in 123, likely for the same reason as the previous war; they were not allowed to visit and trade with each other. Marcius Turbo stationed 1,000 legionaries in the towns Potaissa and Porolissum, which the Romans probably used as the invasion point into Rivulus Dominarum. Marcius Turbo succeeded in defeating the Iazyges; the terms of the peace and the date, however, are not known.

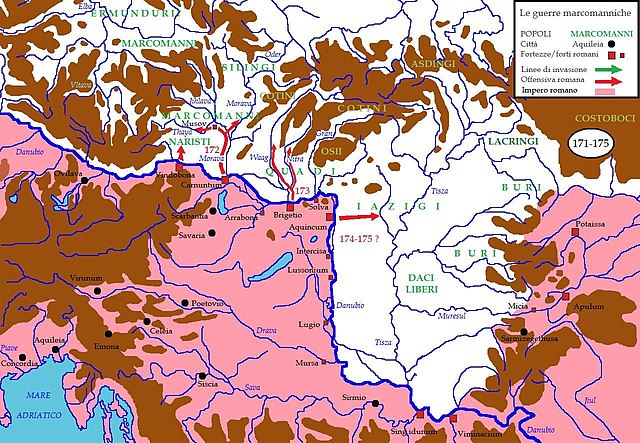

Marcomannic Wars :

The 174 - 175 Roman offensive onto Iazigi In 169, the Iazyges, Quadi, Suebi, and Marcomanni once again invaded Roman territory. The Iazyges led an invasion into Alburnum in an attempt to seize its gold mines. The exact motives for and directions of the Iazyges' war efforts are not known. Marcus Claudius Fronto, who was a general during the Parthian wars and then the governor of both Dacia and Upper Moesia, held them back for some time but was killed in battle in 170. The Quadi surrendered in 172, the first tribe to do so; the known terms of the peace are that Marcus Aurelius installed a client-king Furtius on their throne and the Quadi were denied access to the Roman markets along the limes. The Marcomanni accepted a similar peace but the name of their client-king is not known.

In 173, the Quadi rebelled and overthrew Furtius and replaced him with Ariogaesus, who wanted to enter into negotiations with Marcus. Marcus refused to negotiate because the success of the Marcomannic wars was in no danger. At that point the Iazyges had not yet been defeated by Rome. having not acted, Marcus Aurelius appears to have been unconcerned, but when the Iazyges attacked across the frozen Danube in late 173 and early 174, Marcus redirected his attention to them. Trade restrictions on the Marcomanni were also partially lifted at that time; they were allowed to visit the Roman markets at certain times of certain days. In an attempt to force Marcus to negotiate, Ariogaesus began to support the Iazyges. Marcus Aurelius put out a bounty on him, offering 1,000 aurei for his capture and delivery to Rome or 500 aurei for his severed head. After this, the Romans captured Ariogaesus but rather than executing him, Marcus Aurelius sent him into exile.

In the winter of 173, the Iazyges launched a raid across the frozen Danube but the Romans were ready for pursuit and followed them back to the Danube. Knowing the Roman legionaries were not trained to fight on ice, and that their own horses had been trained to do so without slipping, the Iazyges prepared an ambush, planning to attack and scatter the Romans as they tried to cross the frozen river. The Roman army, however, formed a solid square and dug into the ice with their shields so they would not slip. When the Iazyges could not break the Roman lines, the Romans counter-attacked, pulling the Iazyges off of their horses by grabbing their spears, clothing, and shields. Soon both armies were in disarray after slipping on the ice and the battle was reduced to many brawls between the two sides, which the Romans won. After this battle the Iazyges – and presumably the Sarmatians in general – were declared the primary enemy of Rome.

The Iazyges surrendered to the Romans in March or early April of 175. Their prince Banadaspus had attempted peace in early 174 but the offer was refused and Banadaspus was deposed by the Iazyges and replaced with Zanticus. The terms of the peace treaty were harsh; the Iazyges were required to provide 8,000 men as auxiliaries and release 100,000 Romans they had taken hostage, and were forbidden from living within ten Roman miles (roughly 9 miles (14 km) of the Danube. Marcus had intended to impose even harsher terms; it is said by Cassius Dio that he wanted to entirely exterminate the Iazyges but was distracted by the rebellion of Avidius Cassius.During this peace deal, Marcus Aurelius broke from the Roman custom of Emperors sending details of peace treaties to the Roman Senate; this is the only instance in which Marcus Aurelius is recorded to have broken this tradition. Of the 8,000 auxiliaries, 5,500 of them were sent to Britannia to serve with the Legio VI Victrix, suggesting that the situation there was serious; it is likely the British tribes, seeing the Romans being preoccupied with war in Germania and Dacia, had decided to rebel. All of the evidence suggests the Iazyges' horsemen were an impressive success. The 5,500 troops sent to Britain were not allowed to return home, even after their 20-year term of service had ended. After Marcus Aurelius had beaten the Iazyges; he took the title of Sarmaticus in accordance with the Roman practice of victory titles.

After the Marcomannic Wars :

As part of a treaty made in 183, Commodus forbade the Quadi and the Marcomanni from waging war against the Iazyges, the Buri, or the Vandals, suggesting that at this time all three tribes were loyal client-tribes of Rome. In 214, however, Caracalla led an invasion into the Iazyges' territory. In 236, the Iazyges invaded Rome but were defeated by Emperor Maximinus Thrax, who took the title Sarmaticus Maximus following his victory. The Iazyges, Marcomanni, and Quadi raided Pannonia together in 248, and again in 254. It is suggested the reason for the large increase in the amount of Iazyx raids against Rome was that the Goths led successful raids, which emboldened the Iazyges and other tribes. In 260, the Goths took the cities of Tyras and Olbia, again cutting off the Iazyges' trade with the Pontic Steppe and the Black Sea. From 282 to 283, Emperor Carus lead a successful campaign against the Iazyges.

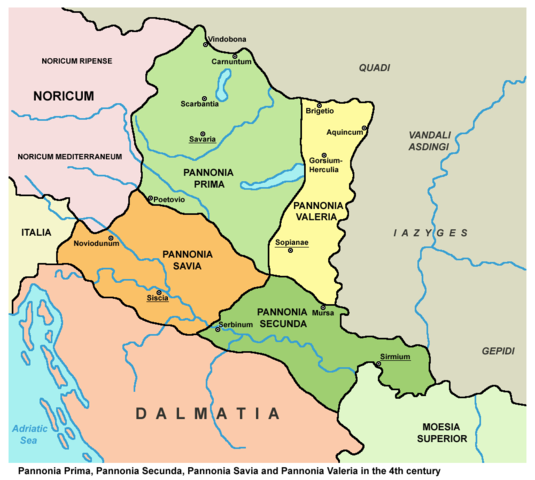

The Iazyges and Carpi raided Roman territory in 293, and Diocletian responded by declaring war. From 294 to 295, Diocletian waged war upon them and won. As a result of the war, some of the Carpi were transported into Roman territory so they could be controlled. From 296 to 298, Galerius successfully campaigned against the Iazyges. In 358, the Iazyges were at war with Rome. In 375, Emperor Valentinian had a stroke in Brigetio while meeting with envoys from the Iazyges. Around the time of the Gothic migration, and most intensely during the reign of Constantine I, a series of earthworks known as the Devil's Dykes (Ördögárok) was built around the Iazyges' territory.

Late history and legacy :

Iazyges in the 4th century at left bank of Danube (Gepids, Hasdingi), neighboring Gotini are replaced with Suebic Quadi In late antiquity, historic accounts become much more diffuse and the Iazyges generally cease to be mentioned as a tribe. Beginning in the 4th century, most Roman authors cease to distinguish between the different Sarmatian tribes, and instead refer to all as Sarmatians. In the late 4th century, two Sarmatian peoples were mentioned ––the Argaragantes and the Limigantes, who lived on opposite sides of the Tisza river. One theory is that these two tribes were formed when the Roxolani conquered the Iazyges, after which the Iazyges became the Limigantes and the Roxolani became the Argaragantes. Another theory is that a group of Slavic tribesmen who gradually migrated into the area were subservient to the Iazyges; the Iazyges became known as the Argaragantes and the Slavs were the Limigantes. Yet another theory holds that the Roxolani were integrated into the Iazyges. Regardless of which is true, in the 5th century both tribes were conquered by the Goths and, by the time of Attila, they were absorbed into the Huns.

Foreign

policy :

Another key part of the relationship between the Roman Empire and the Sarmatian tribes was the settling of tribes in Roman lands, with emperors often accepting refugees from the Sarmatian tribes into nearby Roman territory. When the Huns arrived in the Russian steppes and conquered the tribes that were there, they often lacked the martial ability to force the newly conquered tribes to stay, leading to tribes like the Greuthungi, Vandals, Alans, and Goths migrating and settling within the Roman Empire rather than remaining subjects of the Huns. The Roman Empire benefited from accepting these refugee tribes, and thus continued to allow them to settle, even after treaties were made with Hunnic leaders such as Rugila and Attila that stipulated that the Roman Empire would reject all refugee tribes, with rival or subject tribes of the Huns being warmly received by Roman leaders in the Balkans.

Roxolani

:

List

of princes :

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

.png)