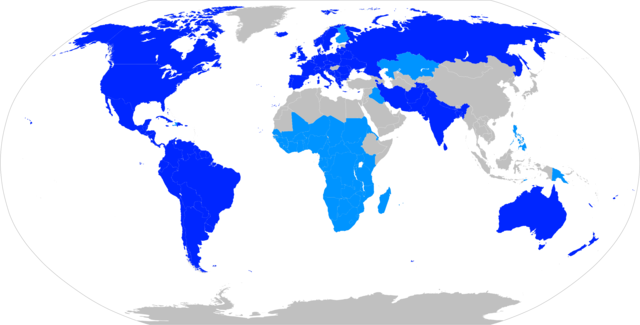

| INDO - EUROPEAN LANGUAGES

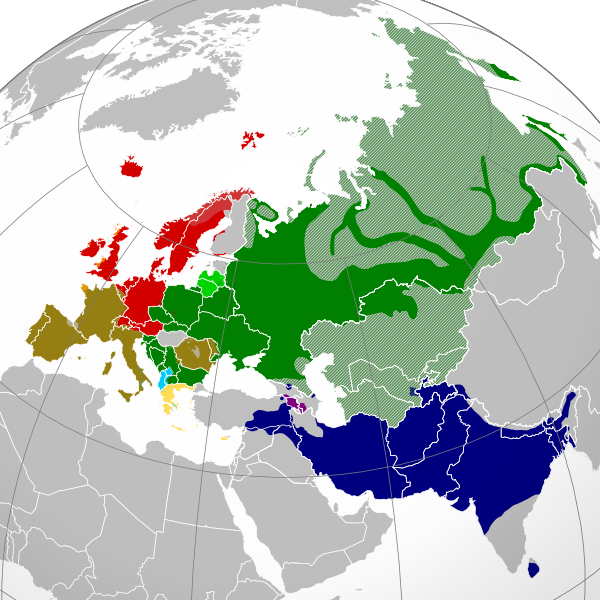

Present-day distribution of Indo-European languages in Eurasia

Dotted/striped

areas indicate where multilingualism is common

The Indo-European languages are a large language family native to western and southern Eurasia. It comprises most of the languages of Europe together with those of the northern Indian Subcontinent and the Iranian Plateau. A few of these languages, such as English, French, Portuguese and Spanish, have expanded through colonialism in the modern period and are now spoken across all continents. The Indo-European family is divided into several branches or sub-families, the largest of which are the Indo-Iranian, Germanic, Romance, and Balto-Slavic groups. The most populous individual languages within them are Spanish, English, Hindustani (Hindi/Urdu), Portuguese, Bengali, Marathi, Punjabi, and Russian, each with over 100 million speakers. German, French, Italian, and Persian have more than 50 million each. In total, 46% of the world's population (3.2 billion) speaks an Indo-European language as a first language, by far the highest of any language family. There are about 445 living Indo-European languages, according to the estimate by Ethnologue, with over two thirds (313) of them belonging to the Indo-Iranian branch.

All Indo-European languages have descended from a single prehistoric language, reconstructed as Proto-Indo-European, spoken sometime in the Neolithic era. Its precise geographical location, the Indo-European urheimat, is unknown and has been the object of many competing hypotheses; the most widely accepted is the Kurgan hypothesis, which posits the urheimat to be the Pontic–Caspian steppe, associated with the Yamnaya culture around 3000 BC. By the time the first written records appeared, Indo-European had already evolved into numerous languages spoken across much of Europe and south-west Asia. Written evidence of Indo-European appeared during the Bronze Age in the form of Mycenaean Greek and the Anatolian languages, Hittite and Luwian. The oldest records are isolated Hittite words and names – interspersed in texts that are otherwise in the unrelated Old Assyrian language, a Semitic language – found in the texts of the Assyrian colony of Kültepe in eastern Anatolia in the 20th century BC. Although no older written records of the original Proto-Indo-Europeans remain, some aspects of their culture and religion can be reconstructed from later evidence in the daughter cultures. The Indo-European family is significant to the field of historical linguistics as it possesses the second-longest recorded history of any known family, after the Afroasiatic family in the form of the Egyptian language and the Semitic languages. The analysis of the family relationships between the Indo-European languages and the reconstruction of their common source was central to the development of the methodology of historical linguistics as an academic discipline in the 19th century.

The Indo-European family is not known to be linked to any other language family through any more distant genetic relationship, although several disputed proposals to that effect have been made.

During the nineteenth century, the linguistic concept of Indo-European languages was frequently used interchangeably with the racial concepts of Aryan and the Biblical concept of Japhetite.

History

of Indo-European linguistics :

Another account was made by Filippo Sassetti, a merchant born in Florence in 1540, who travelled to the Indian subcontinent. Writing in 1585, he noted some word similarities between Sanskrit and Italian (these included devahidio "God", sarpah/serpe "serpent", sapta/sette "seven", asta/otto "eight", and nava/nove "nine"). However, neither Stephens' nor Sassetti's observations led to further scholarly inquiry.

In 1647, Dutch linguist and scholar Marcus Zuerius van Boxhorn noted the similarity among certain Asian and European languages and theorized that they were derived from a primitive common language which he called Scythian. He included in his hypothesis Dutch, Albanian, Greek, Latin, Persian, and German, later adding Slavic, Celtic, and Baltic languages. However, Van Boxhorn's suggestions did not become widely known and did not stimulate further research.

Franz Bopp, pioneer in the field of comparative linguistic studies Ottoman Turkish traveler Evliya Çelebi visited Vienna in 1665–1666 as part of a diplomatic mission and noted a few similarities between words in German and in Persian. Gaston Coeurdoux and others made observations of the same type. Coeurdoux made a thorough comparison of Sanskrit, Latin and Greek conjugations in the late 1760s to suggest a relationship among them. Meanwhile, Mikhail Lomonosov compared different language groups, including Slavic, Baltic ("Kurlandic"), Iranian ("Medic"), Finnish, Chinese, "Hottentot" (Khoekhoe), and others, noting that related languages (including Latin, Greek, German and Russian) must have separated in antiquity from common ancestors.

The hypothesis reappeared in 1786 when Sir William Jones first lectured on the striking similarities among three of the oldest languages known in his time: Latin, Greek, and Sanskrit, to which he tentatively added Gothic, Celtic, and Persian, though his classification contained some inaccuracies and omissions. In one of the most famous quotations in linguistics, Jones made the following prescient statement in a lecture to the Asiatic Society of Bengal in 1786, conjecturing the existence of an earlier ancestor language, which he called "a common source" but did not name :

The Sanscrit [sic] language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure; more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three, without believing them to have sprung from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists.

—

Sir William Jones, Third Anniversary Discourse delivered 2 February

1786, ELIOHS

Franz Bopp wrote in 1816 On the conjugational system of the Sanskrit language compared with that of Greek, Latin, Persian and Germanic and between 1833 and 1852 he wrote Comparative Grammar. This marks the beginning of Indo-European studies as an academic discipline. The classical phase of Indo-European comparative linguistics leads from this work to August Schleicher's 1861 Compendium and up to Karl Brugmann's Grundriss, published in the 1880s. Brugmann's neogrammarian reevaluation of the field and Ferdinand de Saussure's development of the laryngeal theory may be considered the beginning of "modern" Indo-European studies. The generation of Indo-Europeanists active in the last third of the 20th century (such as Calvert Watkins, Jochem Schindler, and Helmut Rix) developed a better understanding of morphology and of ablaut in the wake of Kurylowicz's 1956 Apophony in Indo-European, who in 1927 pointed out the existence of the Hittite consonant h. Kurylowicz's discovery supported Ferdinand de Saussure's 1879 proposal of the existence of coefficients sonantiques, elements de Saussure reconstructed to account for vowel length alternations in Indo-European languages. This led to the so-called laryngeal theory, a major step forward in Indo-European linguistics and a confirmation of de Saussure's theory.[citation needed]

Classification

:

•

Albanian, attested

from the 13th century AD; Proto-Albanian evolved from an ancient

Paleo-Balkan language, traditionally thought to be Illyrian; however,

the evidence supporting this is insufficient.

•

Celtic (from

Proto-Celtic), attested since the 6th century BC; Lepontic inscriptions

date as early as the 6th century BC; Celtiberian from the 2nd century

BC; Primitive Irish Ogham inscriptions from the 4th or 5th century

AD, earliest inscriptions in Old Welsh from the 7th century AD.

Modern Celtic languages include Welsh, Cornish, Breton, Scots Gaelic,

Irish and Manx.

•

Italic (from

Proto-Italic), attested from the 7th century BC. Includes the ancient

Osco-Umbrian languages, Faliscan, as well as Latin and its descendants,

the Romance languages, such as Italian, Venetian, Galician, Sardinian,

Neapolitan, Sicilian, Spanish, French, Romansh, Occitan, Portuguese,

Romanian, and Catalan/Valencian.

•

Ancient Belgian:

hypothetical language associated with the proposed Nordwestblock

cultural area. Speculated to be connected to Italic or Venetic,

and to have certain phonological features in common with Lusitanian.

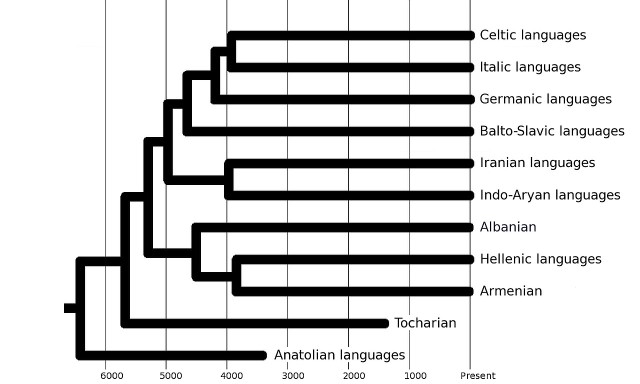

Indo-European family tree in order of first attestation To view large image Click here

Indo-European language family tree based on "Ancestry-constrained phylogenetic analysis of Indo-European languages" by Chang et al Membership of languages in the Indo-European language family is determined by genealogical relationships, meaning that all members are presumed descendants of a common ancestor, Proto-Indo-European. Membership in the various branches, groups and subgroups of Indo-European is also genealogical, but here the defining factors are shared innovations among various languages, suggesting a common ancestor that split off from other Indo-European groups. For example, what makes the Germanic languages a branch of Indo-European is that much of their structure and phonology can be stated in rules that apply to all of them. Many of their common features are presumed innovations that took place in Proto-Germanic, the source of all the Germanic languages.

In

the 21st century, several attempts have been made to model the phylogeny

of Indo-European languages using Bayesian methodologies similar

to those applied to problems in biological phylogeny. Although there

are differences in absolute timing between the various analyses,

there is much commonality between them, including the result that

the first known language groups to diverge were the Anatolian and

Tocharian language families, in that order.

In addition to genealogical changes, many of the early changes in Indo-European languages can be attributed to language contact. It has been asserted, for example, that many of the more striking features shared by Italic languages (Latin, Oscan, Umbrian, etc.) might well be areal features. More certainly, very similar-looking alterations in the systems of long vowels in the West Germanic languages greatly postdate any possible notion of a proto-language innovation (and cannot readily be regarded as "areal", either, because English and continental West Germanic were not a linguistic area). In a similar vein, there are many similar innovations in Germanic and Balto-Slavic that are far more likely areal features than traceable to a common proto-language, such as the uniform development of a high vowel (*u in the case of Germanic, *i/u in the case of Baltic and Slavic) before the PIE syllabic resonants *r, *l, *m, *n, unique to these two groups among IE languages, which is in agreement with the wave model. The Balkan sprachbund even features areal convergence among members of very different branches.

An extension to the Ringe-Warnow model of language evolution, suggests that early IE had featured limited contact between distinct lineages, with only the Germanic subfamily exhibiting a less treelike behaviour as it acquired some characteristics from neighbours early in its evolution. The internal diversification of especially West Germanic is cited to have been radically non-treelike.

Proposed subgroupings :

Hypothetical

Indo-European phylogenetic clades :

Specialists have postulated the existence of higher-order subgroups such as Italo-Celtic, Graeco-Armenian, Graeco-Aryan or Graeco-Armeno-Aryan, and Balto-Slavo-Germanic. However, unlike the ten traditional branches, these are all controversial to a greater or lesser degree.

The Italo-Celtic subgroup was at one point uncontroversial, considered by Antoine Meillet to be even better established than Balto-Slavic. The main lines of evidence included the genitive suffix -i; the superlative suffix -mmo; the change of /p/ to /kw/ before another /kw/ in the same word (as in penkwe > *kwenkwe > Latin quinque, Old Irish cóic); and the subjunctive morpheme -a-. This evidence was prominently challenged by Calvert Watkins; while Michael Weiss has argued for the subgroup.

Evidence for a relationship between Greek and Armenian includes the regular change of the second laryngeal to a at the beginnings of words, as well as terms for "woman" and "sheep". Greek and Indo-Iranian share innovations mainly in verbal morphology and patterns of nominal derivation. Relations have also been proposed between Phrygian and Greek, and between Thracian and Armenian. Some fundamental shared features, like the aorist (a verb form denoting action without reference to duration or completion) having the perfect active particle -s fixed to the stem, link this group closer to Anatolian languages and Tocharian. Shared features with Balto-Slavic languages, on the other hand (especially present and preterit formations), might be due to later contacts.

The Indo-Hittite hypothesis proposes that the Indo-European language family consists of two main branches: one represented by the Anatolian languages and another branch encompassing all other Indo-European languages. Features that separate Anatolian from all other branches of Indo-European (such as the gender or the verb system) have been interpreted alternately as archaic debris or as innovations due to prolonged isolation. Points proffered in favour of the Indo-Hittite hypothesis are the (non-universal) Indo-European agricultural terminology in Anatolia and the preservation of laryngeals. However, in general this hypothesis is considered to attribute too much weight to the Anatolian evidence. According to another view, the Anatolian subgroup left the Indo-European parent language comparatively late, approximately at the same time as Indo-Iranian and later than the Greek or Armenian divisions. A third view, especially prevalent in the so-called French school of Indo-European studies, holds that extant similarities in non-satem languages in general—including Anatolian—might be due to their peripheral location in the Indo-European language-area and to early separation, rather than indicating a special ancestral relationship.Hans J. Holm, based on lexical calculations, arrives at a picture roughly replicating the general scholarly opinion and refuting the Indo-Hittite hypothesis.

Satem and centum languages :

The division of the Indo-European languages into satem and centum groups was put forward by Peter von Bradke in 1890, although Karl Brugmann did propose a similar type of division in 1886. In the satem languages, which include the Balto-Slavic and Indo-Iranian branches, as well as (in most respects) Albanian and Armenian, the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European palatovelars remained distinct and were fricativized, while the labiovelars merged with the 'plain velars'. In the centum languages, the palatovelars merged with the plain velars, while the labiovelars remained distinct. The results of these alternative developments are exemplified by the words for "hundred" in Avestan (satem) and Latin (centum)—the initial palatovelar developed into a fricative [s] in the former, but became an ordinary velar [k] in the latter.

Rather than being a genealogical separation, the centum–satem division is commonly seen as resulting from innovative changes that spread across PIE dialect-branches over a particular geographical area; the centum–satem isogloss intersects a number of other isoglosses that mark distinctions between features in the early IE branches. It may be that the centum branches in fact reflect the original state of affairs in PIE, and only the satem branches shared a set of innovations, which affected all but the peripheral areas of the PIE dialect continuum. Kortlandt proposes that the ancestors of Balts and Slavs took part in satemization before being drawn later into the western Indo-European sphere.

Suggested

macrofamilies :

•

Indo-Uralic,

joining Indo-European with Uralic

•

Eurasiatic, a

theory championed by Joseph Greenberg, comprising the Uralic, Altaic

and various 'Paleosiberian' families (Ainu, Yukaghir, Nivkh, Chukotko-Kamchatkan,

Eskimo-Aleut) and possibly others

Evolution

:

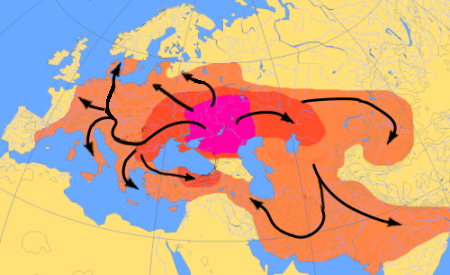

Scheme of Indo-European migrations from ca. 4000 to 1000 BC according to the Kurgan hypothesis The proposed Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European languages, spoken by the Proto-Indo-Europeans. From the 1960s, knowledge of Anatolian became certain enough to establish its relationship to PIE. Using the method of internal reconstruction, an earlier stage, called Pre-Proto-Indo-European, has been proposed.

PIE was an inflected language, in which the grammatical relationships between words were signaled through inflectional morphemes (usually endings). The roots of PIE are basic morphemes carrying a lexical meaning. By addition of suffixes, they form stems, and by addition of endings, these form grammatically inflected words (nouns or verbs). The reconstructed Indo-European verb system is complex and, like the noun, exhibits a system of ablaut.

Diversification :

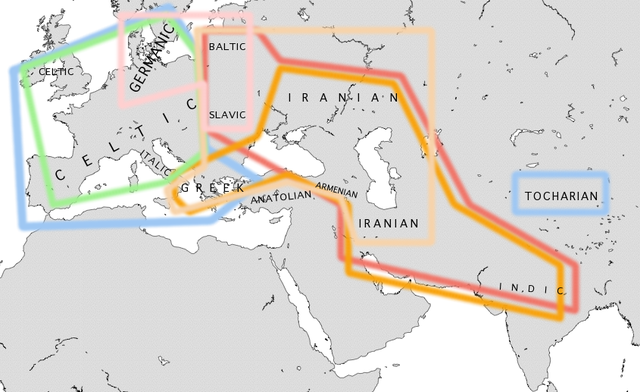

Possible expansion of Indo-European languages according to the Kurgan hypothesis

IE languages 3500 BC

IE languages 2500 BC

IE languages 1500 BC

IE languages 500 AD The diversification of the parent language into the attested branches of daughter languages is historically unattested. The timeline of the evolution of the various daughter languages, on the other hand, is mostly undisputed, quite regardless of the question of Indo-European origins.

Using a mathematical analysis borrowed from evolutionary biology, Don Ringe and Tandy Warnow propose the following evolutionary tree of Indo-European branches :

•

Pre-Anatolian

(before 3500 BC)

David Anthony proposes the following sequence :

•

Pre-Anatolian

(4200 BC)

•

1500–1000

BC : The Nordic Bronze Age develops pre-Proto-Germanic, and the

(pre)-Proto-Celtic Urnfield and Hallstatt cultures emerge in Central

Europe, introducing the Iron Age. Migration of the Proto-Italic

speakers into the Italian peninsula (Bagnolo stele). Redaction of

the Rigved and rise of the Vedic civilization in the Punjab. The

Mycenaean civilization gives way to the Greek Dark Ages. Hittite

goes extinct.

Most noticeable of all :

•

Vedic Sanskrit

(c. 1500–500 BC). This language is unique in that its source

documents were all composed orally, and were passed down through

oral tradition (shakha schools) for c. 2,000 years before ever being

written down. The oldest documents are all in poetic form; oldest

and most important of all is the Rigved (c. 1500 BC).

•

Latin, attested

in a huge amount of poetic and prose material in the Classical period

(c. 200 BC – 100 AD) and limited older material from as early

as c. 600 BC.

•

Luwian, Lycian,

Lydian and other Anatolian languages (c. 1400–400 BC).

•

Old Irish (c.

700–850 AD).

PIE is normally reconstructed with a complex system of 15 stop consonants, including an unusual three-way phonation (voicing) distinction between voiceless, voiced and "voiced aspirated" (i.e. breathy voiced) stops, and a three-way distinction among velar consonants (k-type sounds) between "palatal" k g gh, "plain velar" k g gh and labiovelar kw gw gwh. (The correctness of the terms palatal and plain velar is disputed; see Proto-Indo-European phonology.) All daughter languages have reduced the number of distinctions among these sounds, often in divergent ways.

As an example, in English, one of the Germanic languages, the following are some of the major changes that happened :

1.

As in other centum languages, the "plain velar" and "palatal"

stops merged, reducing the number of stops from 15 to 12.

For

PIE p : piscis vs. fish; pes, pedis vs. foot; pluvium "rain"

vs. flow; pater vs. father

•

The "central"

satem languages (Indo-Iranian, Balto-Slavic, Albanian, and Armenian)

reflect both "plain velar" and labiovelar stops as plain

velars, often with secondary palatalization before a front vowel

(e i e i). The "palatal" stops are palatalized and often

appear as sibilants (usually but not always distinct from the secondarily

palatalized stops).

•

The Indo-Aryan

languages preserve the three series unchanged but have evolved a

fourth series of voiceless aspirated consonants.

•

The Ruki sound

law (s becomes /f/ before r, u, k, i) in the satem languages.

Comparison of conjugations :

While similarities are still visible between the modern descendants and relatives of these ancient languages, the differences have increased over time. Some IE languages have moved from synthetic verb systems to largely periphrastic systems. In addition, the pronouns of periphrastic forms are in brackets when they appear. Some of these verbs have undergone a change in meaning as well.

•

In Modern Irish

beir usually only carries the meaning to bear in the sense of bearing

a child; its common meanings are to catch, grab.

The approximate present-day distribution of Indo-European languages within the Americas by country Romance :

Today, Indo-European languages are spoken by 3.2 billion native speakers across all inhabited continents, the largest number by far for any recognised language family. Of the 20 languages with the largest numbers of native speakers according to Ethnologue, 10 are Indo-European: Spanish, English, Hindustani, Portuguese, Bengali, Russian, Punjabi, German, French, and Marathi, accounting for over 1.7 billion native speakers. Additionally, hundreds of millions of persons worldwide study Indo-European languages as secondary or tertiary languages, including in cultures which have completely different language families and historical backgrounds—there are between 600 million and one billion L2 learners of English alone.

The success of the language family, including the large number of speakers and the vast portions of the Earth that they inhabit, is due to several factors. The ancient Indo-European migrations and widespread dissemination of Indo-European culture throughout Eurasia, including that of the Proto-Indo-Europeans themselves, and that of their daughter cultures including the Indo-Aryans, Iranian peoples, Celts, Greeks, Romans, Germanic peoples, and Slavs, led to these peoples' branches of the language family already taking a dominant foothold in virtually all of Eurasia except for swathes of the Near East, North and East Asia, replacing many (but not all) of the previously-spoken pre-Indo-European languages of this extensive area. However Semitic languages remain dominant in much of the Middle East and North Africa, and Caucasian languages in much of the Caucasus region. Similarly in Europe and the Urals the Uralic languages (such as Hungarian, Finnish, Estonian etc) remain, as does Basque, a pre-Indo-European isolate.

Despite being unaware of their common linguistic origin, diverse groups of Indo-European speakers continued to culturally dominate and often replace the indigenous languages of the western two-thirds of Eurasia. By the beginning of the Common Era, Indo-European peoples controlled almost the entirety of this area: the Celts western and central Europe, the Romans southern Europe, the Germanic peoples northern Europe, the Slavs eastern Europe, the Iranian peoples most of western and central Asia and parts of eastern Europe, and the Indo-Aryan peoples in the Indian subcontinent, with the Tocharians inhabiting the Indo-European frontier in western China. By the medieval period, only the Semitic, Dravidian, Caucasian, and Uralic languages, and the language isolate Basque remained of the (relatively) indigenous languages of Europe and the western half of Asia.

Despite medieval invasions by Eurasian nomads, a group to which the Proto-Indo-Europeans had once belonged, Indo-European expansion reached another peak in the early modern period with the dramatic increase in the population of the Indian subcontinent and European expansionism throughout the globe during the Age of Discovery, as well as the continued replacement and assimilation of surrounding non-Indo-European languages and peoples due to increased state centralization and nationalism. These trends compounded throughout the modern period due to the general global population growth and the results of European colonization of the Western Hemisphere and Oceania, leading to an explosion in the number of Indo-European speakers as well as the territories inhabited by them.

Due to colonization and the modern dominance of Indo-European languages in the fields of politics, global science, technology, education, finance, and sports, even many modern countries whose populations largely speak non-Indo-European languages have Indo-European languages as official languages, and the majority of the global population speaks at least one Indo-European language. The overwhelming majority of languages used on the Internet are Indo-European, with English continuing to lead the group; English in general has in many respects become the lingua franca of global communication.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |