| INDO - SCYTHIANS Indo-Scythian

Kingdom :

Territories (green) and expansion (yellow) of the Indo-Scythian Kingdom at its greatest extent Indo-Scythian Kingdom

c. 150 BCE - 400 CE

Capital : Sigal, Taxila and Mathura

Common languages : Scythian, Greek, Pali (Kharoshthi script), Sanskrit, Prakrit (Brahmi script) and Possibly Aramaic

Religion : Hinduism, Buddhism and Ancient Greek religion

Government : Monarchy

King

• 85 - 60 BCE : Maues

• 10 CE : Hajatria

Historical era : Antiquity

• Established : c. 150 BCE

• Disestablished : 400 CE

Area

20 est. : 2,600,000 km2 (1,000,000 sq mi)

Preceded by

Greco-Bactrian Kingdom

Indo-Greek Kingdom

Maurya Empire

Succeeded by

Kushan Empire

Sassanid Empire

Indo-Parthians

Gupta Empire

Indo-Scythians (also called Indo-Sakas) were a group of nomadic Iranian peoples of Saka and Scythian origin who migrated southward into western and northern South Asia (Sogdiana, Bactria, Arachosia, Gandhar, Sindh, Kashmir, Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Rajasthan, Gujarat and Maharashtra) from the middle of the 2nd century BC to the 4th century AD.

The first Saka king in South Asia was Maues/Moga (1st century BC) who established Saka power in Gandhar, and Indus Valley. The Indo-Scythians extended their supremacy over north-western India, conquering the Indo-Greeks and other local kingdoms. The Indo-Scythians were apparently subjugated by the Kushan Empire, by either Kujul Kadphises or Kanishk. Yet the Saka continued to govern as satrapies, forming the Northern Satraps and Western Satraps.

The power of the Saka rulers started to decline in the 2nd century CE after the Indo-Scythians were defeated by the Shatvahan emperor Gautamiputra Satakarni. Indo-Scythian rule in the northwestern Indian subcontinent ceased when the last Western Satrap Rudrasimha III was defeated by the Gupta emperor Chandragupt II in 395 CE.

The invasion of northern regions of the Indian subcontinent by Scythian tribes from Central Asia, often referred to as the Indo-Scythian invasion, played a significant part in the history of the Indian subcontinent as well as nearby countries. In fact, the Indo-Scythian war is just one chapter in the events triggered by the nomadic flight of Central Asians from conflict with tribes such as the Xiongnu in the 2nd century AD, which had lasting effects on Bactria, Kabul, and the Indian subcontinent as well as far-off Rome in the west, and more nearby to the west in Parthia.

Ancient Roman historians including Arrian and Claudius Ptolemy have mentioned that the ancient Sakas ('Sakai') were nomadic people. However, Italo Ronca, in his detailed study of Ptolemy's chapter vi, states: "The land of the Sakai belongs to nomads, they have no towns but dwell in forests and caves" as spurious.

Origins :

The treasure of the royal burial Tillya Tepe is attributed to 1st century BC Sakas in Bactria The ancestors of the Indo-Scythians are thought to be Sakas (Scythian) tribes.

"One group of Indo-European speakers that makes an early appearance on the Xinjiang stage is the Saka (Ch. Sai). Saka is more a generic term than a name for a specific state or ethnic group; Saka tribes were part of a cultural continuum of early nomads across Siberia and the Central Eurasian steppe lands from Xinjiang to the Black Sea. Like the Scythians whom Herodotus describes in book four of his History (Saka is an Iranian word equivalent to the Greek Scythes, and many scholars refer to them together as Saka-Scythian), Sakas were Iranian-speaking horse nomads who deployed chariots in battle, sacrificed horses, and buried their dead in barrows or mound tombs called kurgans."

Achaemenid

period (6th - 4th century BCE) :

Some scholars, including Michael Witzel and Christopher I. Beckwith suggested that the Shakyas, the clan of the historical Gautam Buddh, were originally Scythians from Central Asia, and that the Indian ethnonym Sakya has the same origin as “Scythian”, called Sakas in India. This would also explain the strong support of the Sakas for the Buddhist faith in India.

The Persians, the Sakas and the Greeks, may have later participated in the campaigns of Chandragupt Maurya to gain the throne of Magadh circa 320 BCE. The Mudrarakshas states that after Alexander's death, an alliance of "Shak-Yavan-Kamboj-Parasik-Bahlik" was used by Chandragupt Maurya in his campaign to take the throne in Magadh and found the Mauryan Empire. The Sakas were the Scythians, the Yavans were the Greeks, and the Parasiks were the Persians.

Yuezhi

expansion (2nd century BCE) :

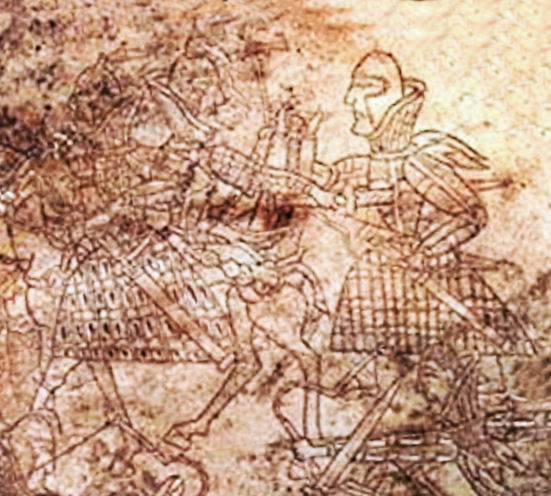

Detail of one of the Orlat plaques seemingly representing Scythian soldiers According to these ancient sources Modu Shanyu of the Xiongnu tribe of Mongolia attacked the Yuezhi (possibly related to the Tocharians who lived in eastern Tarim Basin area) and evicted them from their homeland between the Qilian Shan and Dunhuang around 175 BC. Leaving behind a remnant of their number, most of the population moved westwards into the Ili River area. There, they displaced the Sakas, who migrated south into Ferghana and Sogdiana. According to the Chinese historical chronicles (who call the Sakas, "Sai"): "[The Yuezhi] attacked the king of the Sai who moved a considerable distance to the south and the Yuezhi then occupied his lands."

Sometime after 155 BC, the Yuezhi were again defeated by an alliance of the Wusun and the Xiongnu, and were forced to move south, again displacing the Scythians, who migrated south towards Bactria and present Afghanistan, and south-west closer towards Parthia.

The Sakas seem to have entered the territory of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom around 145 BC, where they burnt to the ground the Greek city of Alexandria on the Oxus. [citation needed] The Yuezhi remained in Sogdiana on the northern bank of the Oxus, but they became suzerains of the Sakas in Bactrian territory, as described by the Chinese ambassador Zhang Qian who visited the region around 126 BC.[citation needed]

In Parthia, between 138–124 BC, a tribe known to ancient Greek scholars as the Sacaraucae (probably from the Old Persian Sakaravaka "nomadic Saka") and an allied, possibly non-Saka/Scythian people, the Massagetae came into conflict with the Parthian Empire. The Sacaraucae-Massagetae alliance won several battles and killed, in succession, the Parthian kings Phraates II and Artabanus I.

The Parthian king Mithridates II finally retook control of parts of Central Asia, first by defeating the Yuezhi in Sogdiana in 115 BC, and then defeating the Scythians in Parthia and Seistan around 100 BC.[citation needed]

After their defeat, the Yuezhi tribes migrated relatively far to the east into Bactria, which they were to control for several centuries, [citation needed] and from which they later conquered northern India to found the Kushan Empire.

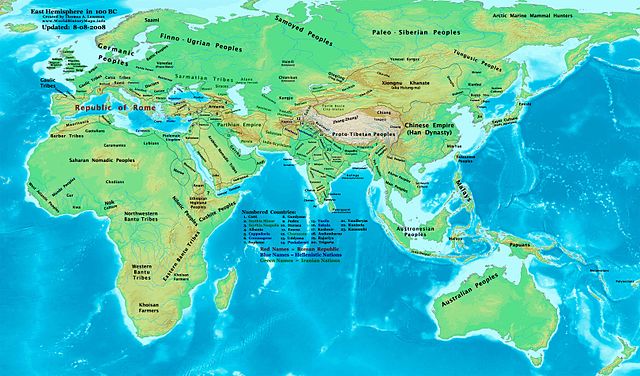

Settlement in Sakastan :

Map of Sakastan around 100 BC The Sakas settled in Drangiana, an area of Southern Afghanistan, western Pakistan and south Iran, which was then called after them as Sakastan or Sistan. From there, they progressively expanded into present day Iran as well as northern India, where they established various kingdoms, and where they are known as "Saka".[citation needed]

The Arsacid emperor Mithridates II (c. 123–88/87 BCE) claimed many successes in battle and added many provinces to the Parthian Empire. Apparently the Scythian hordes that came from Bactria were conquered by him.

Following military pressure from the Yuezhi (precursors of the Kushan), a section of the Indo-Scythians moved from Bactria to Lake Helmond (or Hamun), and settled in or around Drangiana (Sigal), a region which later came to be called "Sakistana of the Skythian Sakai [sic]", towards the end of 1st century BC. The region is still known as Seistan. I The presence of the Sakas in Sakastan in the 1st century BC is mentioned by Isidore of Charax in his "Parthian stations". He explained that they were bordered at that time by Greek cities to the east (Alexandria of the Caucasus and Alexandria of the Arachosians), and the Parthian-controlled territory of Arachosia to the south:

"Beyond

is Sacastana of the Scythian Sacae, which is also Paraetacena, 63

schoeni. There are the city of Barda and the city of Min and the

city of Palacenti and the city of Sigal; in that place is the royal

residence of the Sacae; and nearby is the city of Alexandria (Alexandria

Arachosia), and six villages." Parthian stations, 18.

Asia in 100 BC, showing the Sakas and their neighbors

Scythian devotee, Butkara Stup Ahmad Hassan Dani and professor Karl Jettmar, from the petroglyphs left by Saka soldiers at principle river crossings at Chilas and the Sacred Rock of Hunza, have established the route across the Karakoram mountains used by Maues, the first Indo-Scythian king, to capture Taxila from Indo-Greek King Apollodotus II.

The 1st century AD Periplus of the Erythraean Sea describes the Scythian territories there:

"Beyond this region (Gedrosia), the continent making a wide curve from the east across the depths of the bays, there follows the coast district of Scythia, which lies above toward the north; the whole marshy; from which flows down the river Sinthus, the greatest of all the rivers that flow into the Erythraean Sea, bringing down an enormous volume of water. This river has seven mouths, very shallow and marshy, so that they are not navigable, except the one in the middle; at which by the shore, is the market-town, Barbaricum. Before it there lies a small island, and inland behind it is the metropolis of Scythia, Minnagara; it is subject to Parthian princes who are constantly driving each other out.."

The Indo-Scythians ultimately established a kingdom in the northwest, based near Taxila, with two great Satraps, one in Mathura in the east, and one in Surastrene (Gujarat) in the southwest.

In the southeast, the Indo-Scythians invaded the area of Ujjain, but were subsequently repelled in 57 BC by the Malwa king Vikramaditya. To commemorate the event Vikramaditya established the Vikram era, a specific Indian calendar starting in 57 BC. More than a century later, in AD 78, the Sakas would again invade Ujjain and establish the Saka era, marking the beginning of the long-lived Saka Western Satraps kingdom.

Gandhar and Punjab :

A coin of the Indo-Scythian king Azes The presence of the Scythians in north-western India during the 1st century BCE was contemporary with that of the Indo-Greek Kingdoms there, and it seems they initially recognized the power of the local Greek rulers.

Maues first conquered Gandhar and Taxila around 80 BCE, but his kingdom disintegrated after his death. In the east, the Indian king Vikram retook Ujjain from the Indo-Scythians, celebrating his victory by the creation of the Vikram era (starting 58 BCE). Indo-Greek kings again ruled after Maues, and prospered, as indicated by the profusion of coins from Kings Apollodotus II and Hippostratos. Not until Azes I, in 55 BC, did the Indo-Scythians take final control of northwestern India, with his victory over Hippostratos.

Sculpture :

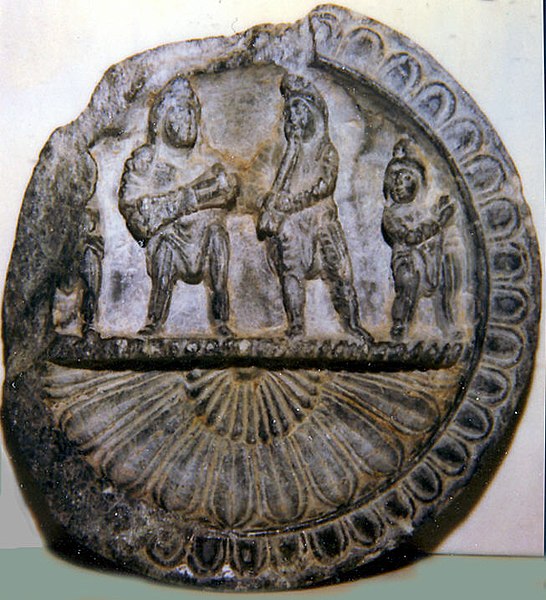

A toilet tray of the type found in the Early Saka layer at Sirkap Several stone sculptures have been found in the Early Saka layer (Layer No4, corresponding to the period of Azes I, in which numerous coins of the latter were found) in the ruins of Sirkap, during the excavations organized by John Marshall.

Bronze coin of Indo-Scythian King Azes A bronze coin of the Indo-Scythian King Azes. Obverse: BASILEWS BASILEWN MEGALOU AZOU, Humped Brahman bull (zebu) walking right, Whitehead symbol 15 (Z in square) above; Reverse: Kharosthi "jha" to right / Kharosthi legend, Lion or leopard standing right, Whitehead symbol 26 above; Reference: Whitehead 259; BMC p. 86, 141.

The Bimaran casket, representing the Buddha surrounded by Brahma (left) and Sakra (right) was found inside a stupa with coins of Azes inside. British Museum Several of them are toilet trays (also called Stone palettes) roughly imitative of earlier, and finer, Hellenistic ones found in the earlier layers. Marshall comments that "we have a praiseworthy effort to copy a Hellenistic original but obviously without the appreciation of form and skill which were necessary for the task". From the same layer, several statuettes in the round are also known, in very rigid and frontal style.

Bimaran

casket :

Mathura area ("Northern Satraps") :

Obv : Bust of King Rajuvul, with Greek legend

The Mathura lion capital is an important Indo-Scythian monument dedicated to the Buddhist religion (British Museum) In northern India, the Indo-Scythians conquered the area of Mathura over Indian kings around 60 BCE. Some of their satraps were Hagamash and Hagan, who were in turn followed by the Saca Great Satrap Rajuvul.

The Mathura lion capital, an Indo-Scythian sandstone capital in crude style, from Mathura in northern India, and dated to the 1st century CE, describes in kharoshthi the gift of a stupa with a relic of the Buddh, by Queen Nadasi Kasa, the wife of the Indo-Scythian ruler of Mathura, Rajuvul. The capital also mentions the genealogy of several Indo-Scythian satraps of Mathura.

Rajuvul apparently eliminated the last of the Indo-Greek kings Strato II around 10 CE, and took his capital city, Sagala.

The coinage of the period, such as that of Rajuvul, tends to become very crude and barbarized in style. It is also very much debased, the silver content becoming lower and lower, in exchange for a higher proportion of bronze, an alloying technique (billon) suggesting less than wealthy finances.

The Mathura lion capital inscriptions attest that Mathura fell under the control of the Sakas. The inscriptions contain references to Kharahostes and Queen Ayasia, the "chief queen of the Indo-Scythian ruler of Mathura, satrap Rajuvul." Kharahostes was the son of Arta as is attested by his own coins. Arta is stated to be brother of King Moga or Maues.

The Indo-Scythian satraps of Mathura are sometimes called the "Northern Satraps", in opposition to the "Western Satraps" ruling in Gujarat and Malwa. After Rajuvul, several successors are known to have ruled as vassals to the Kushans, such as the "Great Satrap" Kharapallan and the "Satrap" Vanaspara, who are known from an inscription discovered in Sarnath, and dated to the 3rd year of Kanishk (c. AD 130), in which they were paying allegiance to the Kushans.

Pataliputra :

Silver coin of Vijayamitra in the name of Azes. Buddhist triratna symbol in the left field on the reverse

Profile of the Indo-Scythian King Azes on one of his coins The text of the Yug Puran describes an invasion of Pataliputra by the Scythians sometimes during the 1st century BC, after seven great kings had ruled in succession in Saket following the retreat of the Yavans. The Yug Puran explains that the king of the Sakas killed one fourth of the population, before he was himself slain by the Kaling king Shat and a group of Sabals (Sabars or Bhils).

Kushan

and Indo-Parthian conquests :

During the latter part of the 1st century AD, the Indo-Parthian overlordship was gradually replaced with that of the Kushans, one of the five tribes of the Yuezhi who had lived in Bactria for more than a century, and were now expanding into India to create a Kushan Empire. The Kushans ultimately regained northwestern India from around AD 75, and the area of Mathura from around AD 100, where they were to prosper for several centuries.[citation needed]

Western Kshatrapas legacy :

Coin of the Western Kshatrapa ruler Rudrasimha I (c. AD 175 to 197), a descendant of the Indo-Scythians Indo-Scythians continued to hold the area of Seistan until the reign of Bahram II (AD 276–293), and held several areas of India well into the 1st millennium: Kathiawar and Gujarat were under their rule until the 5th century under the designation of Western Kshatraps, until they were eventually conquered by the Gupta emperor Chandragupt II (also called Vikramaditya).

Indo-Scythian coinage :

Silver tetradrachm of the Indo-Scythian king Maues (85 – 60 BC) Indo-Scythian coinage is generally of a high artistic quality, although it clearly deteriorates towards the disintegration of Indo-Scythian rule around AD 20 (coins of Rajuvul). A fairly high-quality but rather stereotypical coinage would continue in the Western Satraps until the 4th century.

Indo-Scythian coinage is generally quite realistic, artistically somewhere between Indo-Greek and Kushan coinage. It is often suggested Indo-Scythian coinage benefited from the help of Greek celators (Boppearachchi).

Indo-Scythian coins essentially continue the Indo-Greek tradition, by using the Greek language on the obverse and the Kharoshthi language on the reverse. The portrait of the king is never shown however, and is replaced by depictions of the king on horse (and sometimes on camel), or sometimes sitting cross-legged on a cushion. The reverse of their coins typically show Greek divinities.

Buddhist symbolism is present throughout Indo-Scythian coinage. In particular, they adopted the Indo-Greek practice since Menander I of showing divinities forming the vitarka mudra with their right hand (as for the mudra-forming Zeus on the coins of Maues or Azes II), or the presence of the Buddhist lion on the coins of the same two kings, or the triratana symbol on the coins of Zeionises.

Depiction of Indo-Scythians :

Azilises on horse, wearing a tunic Besides coinage, few works of art are known to indisputably represent Indo-Scythians. Indo-Scythian rulers are usually depicted on horseback in armour, but the coins of Azilises show the king in a simple, undecorated, tunic.[citation needed]

Several

Gandharan sculptures also show foreigners in soft tunics, sometimes

wearing the typical Scythian cap. They stand in contrast to representations

of Kushan men, who seem to wear thick, rigid, tunics, and who are

generally represented in a much more simplistic manner.

Another relief is known where the same type of soldiers are playing musical instruments and dancing, activities which are widely represented elsewhere in Gandharan art: Indo-Scythians are typically shown as reveling devotees.

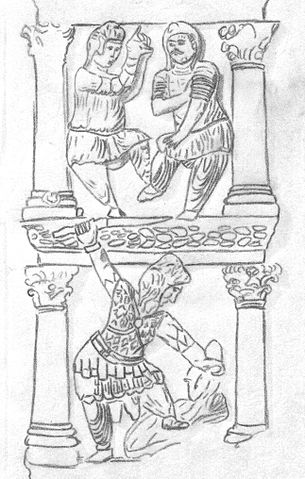

One of the Buner reliefs showing Scythian soldiers dancing. Cleveland Museum of Art

Indo-Scythians pushing along the Greek god Dionysos with Ariadne

Hunting scene

Hunting scene Stone palettes :

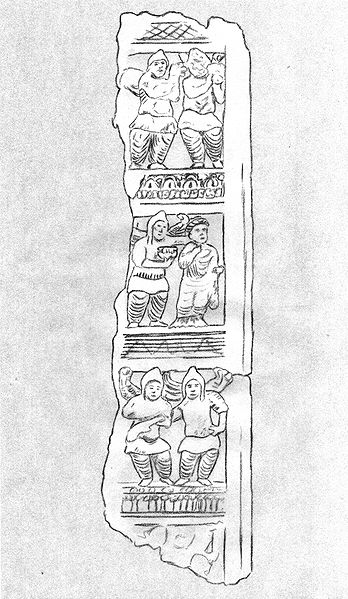

Numerous stone palettes found in Gandhar are considered good representatives of Indo-Scythian art. These palettes combine Greek and Iranian influences, and are often realized in a simple, archaic style. Stone palettes have only been found in archaeological layers corresponding to Indo-Greek, Indo-Scythian and Indo-Parthian rule, and are essentially unknown in the preceding Mauryan layers or the succeeding Kushan layers.

Very often these palettes represent people in Greek dress in mythological scenes, a few in Parthian dress (head-bands over bushy hair, crossed-over jacket on a bare chest, jewelry, belt, baggy trousers), and even fewer in Indo-Scythian dress (Phrygian hat, tunic and comparatively straight trousers). A palette found in Sirkap and now in the New Delhi Museum shows a winged Indo-Scythian horseman riding winged deer, and being attacked by a lion.

The

Indo-Scythians and Buddhism :

Royal dedications :

The Bajaur casket was dedicated by Indravarman, Metropolitan Museum of Art Several Indo-Scythian kings after Azes are known for making Buddhist dedications in their name, on plaques or reliquaries :

•

Patika Kusulaka

(25 BCE – 10 CE) related his donation of a relic of the Buddh

Shakyamuni to a Buddhist monastery, in the Taxila copper plate.

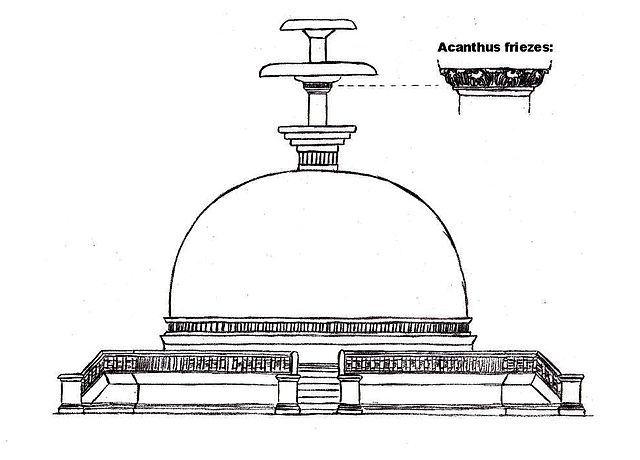

Buddhist stups during the late Indo-Greek/Indo-Scythian period were highly decorated structures with columns, flights of stairs, and decorative Acanthus leaf friezes. Butkara stupa, Swat, 1st century BC.

Possible Scythian devotee couple (extreme left and right, often described as "Scytho-Parthian"), around the Buddh, Brahma and Indra Excavations at the Butkar Stup in Swat by an Italian archaeological team have yielded various Buddhist sculptures thought to belong to the Indo-Scythian period. In particular, an Indo-Corinthian capital representing a Buddhist devotee within foliage has been found which had a reliquary and coins of Azes buried at its base, securely dating the sculpture to around 20 BC. A contemporary pilaster with the image of a Buddhist devotee in Greek dress has also been found at the same spot, again suggesting a mingling of the two populations. Various reliefs at the same location show Indo-Scythians with their characteristic tunics and pointed hoods within a Buddhist context, and side-by-side with reliefs of standing Buddhs.

Gandharan

sculptures :

Mathura

lion capital :

"sarvabudhana puya dhamasa puya saghasa puya"

Indo-Corinthian capital from Butkar Stup, dated to 20 BC, during the reign of Azes II. Turin City Museum of Ancient Art

Dancing Indo-Scythians (top) and hunting scene (bottom). Buddhist relief from Swat, Gandhar

Butkar doorjamb, with Indo-Scythians dancing and reveling. On the back side is a relief of a standing Buddh

Statue with inscription mentioning "year 318", probably 143 CE. The two devotees on the right side of the pedestal are in Indo-Scythian suit (loose trousers, tunic, and hood) Indo-Scythians in Western sources :

This section does not cite any sources.

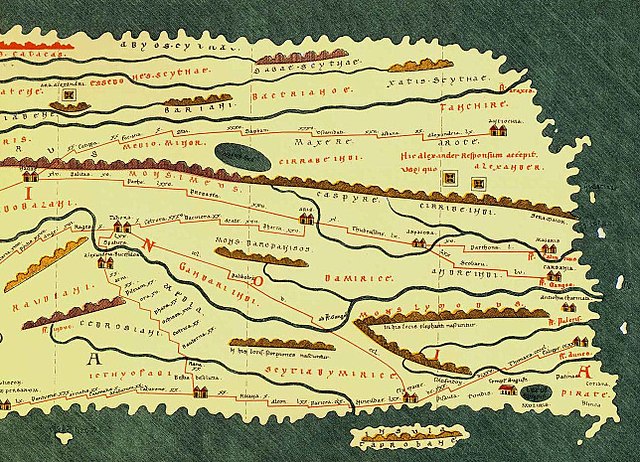

"Scythia" appears around the mouth of the river Indus in the Roman period Tabula Peutingeriana The country of Scythia in the area of Pakistan, and especially around the mouth of the Indus with its capital at Minnagar (modern day Karachi) is mentioned extensively in Western maps and travel descriptions of the period. The Ptolemy world map, as well as the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea mention prominently, the country of Scythia on the Indus Valley, as well as Roman Tabul Peutingeriana. The Periplus states that Minnagar was the capital of Scythia, and that Parthian Princes from within it were fighting for its control during the 1st century AD. It also distinguishes Scythia with Ariaca further east (centred in Gujarat and Malwa), over which ruled the Western Satrap king Nahapana.

Indo-Scythians

in Indian literature :

Coin of Azes, with king seated, holding a drawn sword and a whip A section of the Central Asian Scythians (under Sai-Wang) is said to have taken southerly direction and after passing through the Pamirs it entered the Chipin or Kipin after crossing the Hasuna-tu (Hanging Pass) located above the valley of Kand in Swat country. Chipin has been identified by Pelliot, Bagchi, Raychaudhury and some others with Kashmir while other scholars identify it with Kapisha (Kafirstan). The Sai-Wang had established his kingdom in Kipin. S. Konow interprets the Sai-Wang as Saka Murunda of Indian literature, Murund being equal to Wang i.e. king, master or lord, but Bagchi who takes the word Wang in the sense of the king of the Scythians but he distinguishes the Sai Sakas from the Murund Sakas. There are reasons to believe that Sai Scythians were Kamboj Scythians and therefore Sai-Wang belonged to the Scythianised Kambojs (i.e. Param-Kambojs) of the Transoxiana region and came back to settle among his own stock after being evicted from his ancestral land located in Scythia or Shakadvip. King Moga or Maues could have belonged to this group of Scythians who had migrated from the Sai country (Central Asia) to Chipin.

Establishment of Malech Kingdoms in Northern India :

Coin of Maues depicting Balaram, 1st century BC. British Museum The mixed Scythian hordes that migrated to Drangiana and surrounding regions later spread further into north and south-west India via the lower Indus valley. Their migration spread into Sovir, Gujarat, Rajasthan and northern India, including kingdoms in the Indian mainland.

There are important references to the warring Malech hordes of the Sakas, Yavans, Kambojs and Pahlavs in the Bal Kand of the Valmiki Ramayan. H. C. Raychadhury glimpses in these verses the struggles between the Hindus and the invading hordes of Malech barbarians from the northwest. The time frame for these struggles is the 2nd century BC onwards. Raychadhury fixes the date of the present version of the Valmiki Ramayan around or after the 2nd century AD.

Mahabharat too furnishes a veiled hint about the invasion of the mixed hordes from the northwest. Van Parv by Mahabharat contains verses in the form of prophecy deploring that "......the Malechs (barbaric) kings of the Shaks, Yavans, Kambojs, Bahliks, etc. shall rule the earth un-righteously in Kaliyug..."

According to H. C. Ray Chaudhury, this is too clear a statement to be ignored or explained away.[citation needed]

Evidence about joint invasions :

"Scythian" soldier, Nagarjunakonda The Scythian groups that invaded India and set up various kingdoms included, besides the Sakas, other allied tribes, such as the Medii, Xanthii, and Massagetae. These peoples were all absorbed into the community of Kshatriyas of mainstream Indian society.

The Shaks were formerly a people of the trans-Hemodos region—the Shakadvip of the Purans or the Scythia of the classical writings. Isidor of Charax (beginning of 1st century AD) attests them in Sakastan (modern Seistan). The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (c. AD 70–80) also attests a Scythian district in lower Indus with Minnagra as its capital. Ptolemy (c. AD 140) also attests to an Indo-Scythia in south-western India which comprised the Patalene and Surastrene (Saurashtra) territories.

The 2nd century BC Scythian invasion of India, was in all probability carried out jointly by the Sakas, Pahlavs, Kambojs, Parads, Rishiks and other allied tribes from the northwest.

Main

Indo-Scythian rulers :

Drachm of Parataraj Bhimarjun Obv : Robed bust of Bhimarjun left, wearing tiara-shaped diadem

Rev : Swastik with legend surrounding

• 1.70g.

Senior (Indo-Scythian) 286.1 (Bhimajhuna)

Minor

local rulers

• Rudrasimha

III (388–395) Coin of

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |