| IRANIAN HUNS

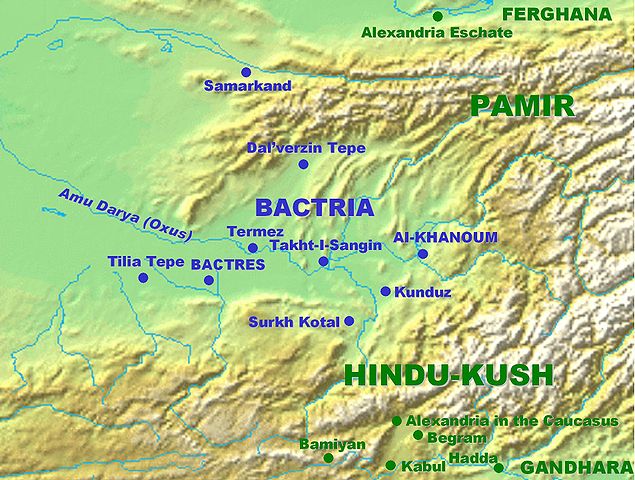

Bactria and the Hindu Kush The term Iranian Huns is sometimes used for a group of different tribes that lived in Afghanistan and neighboring areas between the fourth and seventh centuries and expanded into northwest India. They are roughly equivalent to the Huns. They also threatened the northeast borders of Sasanian Persia and forced the Shahs to lead many ill-documented campaigns against them.

The term was introduced by Robert Göbl in the 1960s and is based on his study of coins. The term "Iranian Huns" coined by Göbl has been sometimes accepted in research, especially in German academia, and reflects how some of the namings and inscriptions of the Kidarites and Hephthalites used an Iranian language, and the bulk of the population they ruled was Iranian. Their origin is controversially discussed. While Göbl describes four groups, recent research sometimes describes the Xionites as a fifth group. In recent research, it is debated whether the new arrivals came as one wave or several waves of different peoples.

"Hun" is used in the broad sense and these people may have been partly non-Iranian. Until the spread of Islam and the re-appearance of the Chinese under the Tang about 700 AD, the sources for central Asian history are poor.

Related to the Iranian Huns are the Uar, Hunas and uncertain terms from various languages like "White Hun", "Red Hun" and others.

Problems

with sources and names :

In the fourth century various central Asian tribes began to attack the Persian Sasanian Empire. The sources sometimes call these people 'Huns', but their origin is unclear. It is probable that they were not related to the Huns who appeared on the south Russian steppe about 375 and attacked the Roman Empire. The two terms should be clearly separated. Like 'Scythian', ‘Hun’ in its various forms was used loosely by ancient historians to refer to various steppe tribes of which they knew little. In modern research, it is often accepted that the term 'Hun' was often used, because of its fame, for various mixed groups and is not to be understood as the name of a concrete ethnic group.

Xionites

:

Ca. 350 a group called the Xionites began to attack the Sassanid Empire. They conquered Bactria, but Shapur II eventually defeated them. Later they allied with the Persians, participated in the Roman-Persian War and joined in the Siege of Amida (359) under their king Grumbates. Written reports come from Ammianus Marcellinus, among others. The Middle Persian term Xyon seems to be related to both 'Xionite' and 'Hun' but does not imply that all groups with this name were related or ethnically homogenous. Among the Iranian Huns, except possibly the Xionites, we can recognize definite Iranian elements, notably the Bactrian language as an administrative language and coin inscriptions.

Kidarites :

Portrait of Kidarites king Kidara, circa 350-386. The coinage of

the Kidarite Huns imitated Sasanian imperial coinage, with the exception

that they displayed clean-shaven faces, instead of the beards of

the Sasanians, a feature relating them to Altaic rather than Iranian

lineage.

The name Kidarites comes from their first known ruler, Kidara (circa 350-385). They made coins in imitation of the Kushano-Sasanids who had previously ruled the area. Many coin-hoards have been found in the Kabul area which allows us to date the start of their rule to about 380. Kidarite coins found in Gandhar suggest that their rule sometimes extended into northern India. Their coins are inscribed in Bactrian, Sogdian and Middle Persian and in the Brahmi script.

Their power fell in the later fifth century. Their capital, Balkh, fell in 467 probably after a great victory of Peroz I over their king Kunkhas. Their rule in Gandhara lasted until at least 477, for in that year they sent an embassy to the Northern Wei dynasty. They seem to have held out in Kashmir a little longer, and then all traces disappear. By this time the Hephthalites had established themselves in Bactria and the Alkhons had driven the Kidarites out of the land south of the Hindu Kush.

Alkhons :

The second wave was the Alkhons who established themselves in the Kabul area around 400. Their history must be reconstructed almost exclusively from coin-hoards. Their coins are based on Sassanid models, probably because they took over the Persian mint at Kabul. The Bactrian word "Alxanno" is stamped on their coins, from which we derive the name "Alkhon". It is not clear whether this word means a tribe, or a ruler, or is a royal title.

Under their king Khingil (died about 490) they attacked Gandhar and drove out the Kidarites. Their following attacks on Indian princes seem to have been unsuccessful. In the early sixth century they expanded from Gandhar to northwest India and practically destroyed the rule of the Guptas, whose coins they imitated.

This claim of an Alkhon invasion is based entirely on coin-finds since Indian sources call all of the northern invaders 'Huns', including perhaps the Hephthalites. Under Toraman and his son Mihirakul (515-540/50?) they were especially aggressive. Mihirakul is portrayed negatively and is accused of persecuting Buddhists. Around the middle of the sixth century their power in north India broke down. Mihirakul suffered a serious defeat in 528 and thereafter his power was limited. His capital was Sakal in Punjab which was once an important Indo-Greek center. After his death (550?) they stopped pressing their attacks. Despite its short duration the Hun invasion was politically and culturally devastating for India. Later some of the Alkhons seem to have returned to Bactria.

Nezak :

Göbl’s third wave were the Nezak Huns who settled around Kabul. Early scholars called them 'Napki'. The exact chronology is unclear. The first written accounts come from the early seventh century. Some place their foundation in the late sixth century after the fall of the Hephthalites. The coins imply a foundation in the late fifth century. If we accept the early dating they were under pressure from the Hephthalites, but by the later dating they profited from the Hephthalite collapse.

Their coins are strongly based on Sassanid models but are clearly recognizable by their distinctive bulls-head crowns which allow the coins to be divided into types. It seems that returning Alkhon groups met the Nizaks and produced an Alkhon-Nizak mixed language.

It is certain that they expanded to Gandhar and minted coins there. Chinese sources from the early seventh century prove that their capital was Kapis. Their remnants south of the Hindu Kush seem to have been destroyed by the Arab conquest in the late seventh century.

Hephthalites :

The fourth and most important wave were the Hephthalites who arrived in the mid fifth century. As with the other groups an exact chronology is difficult to establish. From later Perso-Arabic sources such as Al-Tabari it appears that they were opponents of the Persians already in the first half of the fifth century, although the sources use the vague term “Turk”. The few reports of Greco-Roman authors, who often had little knowledge of events so far east, made little distinction between the different groups and it seems more probable that they referred to other Iranian Huns who arrived before the Hephthalites proper. They were called "White Huns" by Procopius who gives some information. Their coins are based on current Persian models.

To the end of the fifth century they had spread from eastern Tocharistan (Bactria) and brought several neighboring areas under control. They expanded not to India but to Transoxana. The Hunas reported from Indian sources were probably Alkhons (see above). By the beginning of the sixth century they controlled a significant area in Bactria and Sogdia.

The Hephthalites had many conflicts with the Persians. In 484 Peroz I fell in battle against the Hephthalites, who had defeated him before. In 498/99 they restored Kavadh I to the throne. The Persians seem to have paid tribute, at least some of the time. Among the Iranian Huns the Hephthalites were the most serious threat to the Persians. Syrian and Armenian sources report repeated Sassanid attempts to secure their northeast border which led to disaster for Peroz I who had previously defeated the Kidarites. According to Procopius they had an effective ruling system with a king at the top and, at least after the conquest of Bactria and Sogdia, were no longer nomads. They used Bactrian language as an administrative language and used the urban centers of their realm, notably Gorgo (location?) and Balkh. Around 560 their realm was destroyed by an alliance of Persians and Gokturks. Hephthalite remnants lasted until the Arab conquest in the late seventh and early eighth centuries.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

.jpg)