| KALASH PEOPLE

Kalash women Regions

with significant populations : Chitral District, Pakistan

The Kalash also called Waigali or Wai, are a Dardic Indo-Aryan indigenous people residing in the Chitral District of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan.

They speak the Kalash language, from the Dardic family of the Indo-Aryan branch. They are considered unique among the people of Pakistan. They are also considered to be Pakistan's smallest ethnoreligious group, practising a religion which some authors characterise as a form of animism, while academics classify it as "a form of ancient Hinduism".

The term is used to refer to many distinct people including the Väi, the Cima-nišei, the Vântä, plus the Ashkun- and Tregami-speakers. The Kalash are considered to be an indigenous people of Asia, with their ancestors migrating to Chitral valley from another location possibly further south, which the Kalash call "Tsiyam" in their folk songs and epics. Some of the Kalash traditions consider the various Kalash people to have been migrants or refugees.They are also considered by some to have been descendants of Gandhari people.

The neighbouring Nuristani people of the adjacent Nuristan (historically known as Kafiristan) province of Afghanistan once had the same culture and practised the same faith adhered to by the Kalash though with some distinctions.

The first historically recorded Islamic invasions of their lands were by the Ghaznavids in the 11th century while they themselves are first attested in 1339 during Timur's invasions. Nuristan had been forcibly converted to Islam in 1895–96, although some evidence has shown the people continued to practice their customs. The Kalash of Chitral have maintained their own separate cultural traditions.

Culture

:

Kalash mythology and folklore has been compared to that of ancient Greece, but they are much closer to the Hindu traditions in other parts of the Indian subcontinent. The Kalash have fascinated anthropologists due to their unique culture compared to the rest in that region.

Language

:

Customs :

Kalash girl There is some controversy over what defines the ethnic characteristics of the Kalash. Although quite numerous before the 20th century, the non-Muslim minority has seen its numbers dwindle over the past century. A leader of the Kalash, Saifulla Jan, has stated, "If any Kalash converts to Islam, they cannot live among us anymore. We keep our identity strong." About three thousand have converted to Islam or are descendants of converts, yet still live nearby in the Kalash villages and maintain their language and many aspects of their ancient culture. By now, sheikhs, or converts to Islam, make up more than half of the total Kalash-speaking population.

Kalash women usually wear long black robes, often embroidered with cowrie shells. For this reason, they are known in Chitral as "the Black Kafirs". Men have adopted the Pakistani shalwar kameez, while children wear small versions of adult clothing after the age of four.

In contrast to the surrounding Pakistani culture, the Kalash do not in general separate males and females or frown on contact between the sexes. However, menstruating girls and women are sent to live in the "bashaleni", the village menstrual building, during their periods, until they regain their "purity". They are also required to give birth in the bashaleni. There is also a ritual restoring "purity" to a woman after childbirth which must be performed before a woman can return to her husband. The husband is an active participant in this ritual.

Girls are initiated into womanhood at an early age of four or five and married at fourteen or fifteen. If a woman wants to change husbands, she will write a letter to her prospective husband informing him about how much her current husband paid for her. This is because the new husband must pay double if he wants her.

Marriage by elopement is rather frequent, also involving women who are already married to another man. Indeed, wife-elopement is counted as one of the "great customs" (ghona dastur) together with the main festivals. Wife-elopement may lead in some rare cases to a quasi-feud between clans until peace is negotiated by mediators, in the form of the double bride-price paid by the new husband to the ex-husband.

Kalash lineages (kam) separate as marriageable descendants have separated by over seven generations. A rite of "breaking agnation" (tatbre chin) marks that previous agnates (tatbre) are now permissible affines (därak "clan partners"). Each kam has a separate shrine in the clan's Jestak-han, the temple to lineal or familial goddess Jestak.[citation needed]

The historical religious practices of the Pahari people are similar to those of the Kalash people in that they "ate meat, drank alcohol, and had shamans". In addition, the Pahari people "had rules of lineage exogamy that produced a segmentary system closely resembling the Kalash one".

Festivals :

Celebrating Joshi, Kalash women and men dance and sing their way from the dancing ground to the village arena, the Charso, for the end of the day's festivities

Chilam Joshi festival celebrations The three main festivals (khawsángaw) of the Kalash are the Chilam Joshi in middle of May, the Uchau in autumn, and the Caumus in midwinter. The pastoral god Sorizan protects the herds in Fall and Winter and is thanked at the winter festival, while Goshidai does so until the Pul festival (pu. from *purna, full moon in Sept.) and is thanked at the Joshi (josi, žoši) festival in spring. Joshi is celebrated at the end of May each year. The first day of Joshi is "Milk Day", on which the Kalash offer libations of milk that have been saved for ten days prior to the festival.

The most important Kalash festival is the Chawmos (cawmos, ghona chawmos yat, Khowar "chitrimas" from *caturmasya, CDIAL 4742), which is celebrated for two weeks at winter solstice (c. 7–22 December), at the beginning of the month chawmos mastruk. It marks the end of the year's fieldwork and harvest. It involves much music, dancing, and goats killed for consumption as food. It is dedicated to the god Balimain who is believed to visit from the mythical homeland of the Kalash, Tsyam (Tsiyam, tsíam), for the duration of the feast.

At Chaumos, impure and uninitiated persons are not admitted; they must be purified by waving a fire brand over women and children and by a special fire ritual for men, involving a shaman waving juniper brands over the men. The 'old rules' of the gods (Devalog, devlok) are no longer in force, as is typical for year-end and carnival-like rituals. The main Chaumos ritual takes place at a Tok tree, a place called Indra's place, "indrunkot", or "indréyin". Indrunkot is sometimes believed to belong to Balumain's brother, In(dr), lord of cattle.

The men must be divided into two parties: the pure ones have to sing the well-honored songs of the past, but the impure sing wild, passionate, and obscene songs, with an altogether different rhythm. This is accompanied by a 'sex change': men dress as women, women as men (Balumain also is partly seen as female and can change between both forms at will).

At this crucial moment the pure get weaker, and the impure try to take hold of the (very pure) boys, pretend to mount them "like a hornless ram", and proceed in snake procession. At this point, the impure men resist and fight. When the "nagayro" song with the response "han sarías" (from *samriyate 'flows together', CDIAL 12995) is voiced, Balumain showers all his blessings and disappears. He gives his blessings to seven boys (representing the mythical seven of the eight Devlok who received him on arrival), and these pass the blessings on to all pure men.

In myth, Mahandeu had cheated Balumain from superiority, when all the gods had slept together (a euphemism) in the Shawalo meadow; therefore, he went to the mythical home of the Kalash in Tsiyam (tsíam), to come back next year like the Vedic Indra (Rigved 10.86). If this had not happened, Balumain would have taught humans how to have sex as a sacred act. Instead, he could only teach them fertility songs used at the Chaumos ritual. He arrives from the west, the Bashgal valley, in early December, before solstice, and leaves the day after. He was at first shunned by some people, who were annihilated. He was, however, received by seven Devlok and they all went to several villages, such as Batrik village, where seven pure, young boys received him whom he took with him. Therefore, nowadays, one only sends men and older boys to receive him. Balumain is the typical culture hero. He told people about the sacred fire made from junipers, about the sowing ceremony for wheat that involved the blood of a small goat, and he asked for wheat tribute (hushak) for his horse. Finally, Balumain taught how to celebrate the winter festival. He was visible only during his first visit, now he is just felt to be present.

During the winter the Kalash play an inter-village tournament of Chikik Gal (ball game) in which villages compete against each other to hit a ball up and down the valley in deep snow.[citation needed]

Religion

:

According to Sanskrit linguist Michael Witzel, the traditional Kalash religion shares "many of the traits of myths, ritual, society, and echoes many aspects of Rigvedic [religion]" but not of the post-Rigvedic religion that later developed in other parts of India. Kalash culture and belief system differ from the various ethnic groups surrounding them but are similar to those practised by the neighbouring Nuristanis in northeast Afghanistan before their forced conversion to Islam.

Various writers have described the faith adhered to by the Kalash in different ways. University of Rochester social anthropologist and professor Barbara A. West, with respect to the Kalash states in the text Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania that their "religion is a form of Hinduism that recognizes many gods and spirits" and that "given their Indo-Aryan language ... the religion of the Kalash is much more closely aligned to the Hinduism of their Indian neighbors than to the religion of Alexander the Great and his armies." The journalist Frud Bezhan incorporates all of these perspectives, describing the religion followed by the Kalash as being "a form of ancient Hinduism infused with old pagan and animist beliefs." M. Witzel describes both pre-Vedic and Vedic influences on the form of ancient Hinduism adhered to by the Kalash.

The isolated Kalash have received strong religious influences from pre-Islamic Nuristan. Richard Strand, a prominent expert on languages of the Hindu Kush, spent three decades in the Hindukush. He noted the following about the pre-Islamic Nuristani religion:

"Before their conversion to Islâm the Nuristânis practised a form of ancient Hinduism, infused with accretions developed locally. They acknowledged a number of human-like deities who lived in the unseen Deity World (Kâmviri d'e lu; cf. Sanskrit dev lok)."

Deities

:

"In myth it is notably the role of Indra, his rainbow and his eagle who is shot at, the killing of his father, the killing of the snake or of a demon with many heads, and the central myth of releasing the Sun from an enclosure (by Mandi < Mahan Dev). There are echoes of the Purusa myth, and there is the cyclical elevation of Yam Raj (Imra) to sky god (Witzel 1984: 288 sqq., pace Fussman 1977: 70). Importantly, the division between two groups of deities (Devlog) and their intermarriage (Imra's mother is a 'giant') has been preserved, and this dichotomy is still re-enacted in rituals and festivals, especially the Chaumos. Ritual still is of IIr.type: Among the Kalash it is basically, though not always, temple-less, involving fire, sacred wood, three circumambulations, and the *hotr. Some features already have their Vedic, and no longer their Central Asian form (e.g. dragon > snake)."

Mahandeo

:

Imra

:

Indra

:

Warén(dr-) or In Warin is the mightiest and most dangerous god. Even the recently popular Balumain (balimaín, K.) has taken over some of Indra's features: He comes from the outside, riding on a horse. Balumain is a culture hero who taught how to celebrate the Kalash winter festival (Chaumos). He is connected with Tsyam, the mythological homeland of the Kalash. Indra has a demon-like counterpart, Jestan, who appears on earth as a dog; the gods (Devalog, Dewalók) are his enemies and throw stones at him, the shooting stars.

Munjem

Malék :

Jestak

:

Suchi,

Varoti, and Jach :

The religion and culture held by the Kalash has also been influenced by Islamic ideology and culture. Their belief in one supreme God is one example of Muslim influence. They also use some Arabic and Persian words to refer to God.

Ritual :

A drummer during the Joshi festival in Bumberet, Pakistan. Drumming is a male occupation among the Kalash people These deities have shrines and altars throughout the valleys, where they frequently receive goat sacrifices. In 1929, as Georg Morgenstierne testifies, such rituals were still carried out by Kalash priests, "ištikavan" 'priest' (from ištikhék 'to praise a god'). This institution has since disappeared but there still is the prominent one of shamans (dehar). Witzel writes that "In Kalash ritual, the deities are seen, as in Vedic ritual (and in Hindu Puja), as temporary visitors." Mahandeo shrines are a wooden board with four carved horse heads (the horse being sacred to Kalash) extending out, in 1929 still with the effigy of a human head inside holes at the base of these shrines while the altars of Sajigor are of stone and are under old juniper, oak and cedar trees.

Horses, cows, goats and sheep were sacrificed. Wine is a sacred drink of Indr, who owns a vineyard (Indruakun in the Kafiristani wama valley contained both a sacred vineyard and shrine (Idol and altar below a great juniper tree) along with 4 large vates carved out of rocks)—that he defends against invaders. Kalash rituals are of the potlatch type; by organising rituals and festivals (up to 12; the highest called biramor) one gains fame and status. As in the Veda, the former local artisan class was excluded from public religious functions.

There is a special role for prepubescent boys, who are treated with special awe, combining pre-sexual behaviour and the purity of the high mountains, where they tend goats for the summer month. Purity is very much stressed and centered around altars, goat stables, the space between the hearth and the back wall of houses and in festival periods; the higher up in the valley, the more pure the location.

By contrast, women (especially during menstruation and giving birth), as well as death and decomposition and the outside (Muslim) world are impure, and, just as in the Veda and Avesta, many cleansing ceremonies are required if impurity occurs.

Crows represent the ancestors, and are frequently fed with the left hand (also at tombs), just as in the Ved. The dead are buried above ground in ornamented wooden coffins. Wooden effigies are erected at the graves of wealthy or honoured people.

Music

:

•

wãc –

A small hourglass-shaped drum; this is made from 'chizhin' (pine

wood), 'kuherik' (pine nut wood), or 'az'a'i' (apricot (tree) wood).

It is played with a larger drum called a 'dãu' for the Kalash

dances.

Birir Valley The Bumburet and Rumbur valleys join at 35°44'20 N 71°43'40 E (1,640 m), joining the Kunar at the village of Ayrun (35°42'52 N 71°46'40 E, 1,400 m) and they each rise to passes connecting to Afghanistan's Nuristan Province at about 4,500 m.[citation needed]

The Birir Valley opens towards the Kunar at the village of Gabhirat (35°40'8 N 71°45'15 E, 1,360 m). A pass connects [citation needed] the Birir and Bumburet valleys at about 3,000 m. The Kalash villages in all three valleys are located at a height of approximately 1,900 to 2,200 m.[citation needed]

The region is extremely fertile, covering the mountainside in rich oak forests and allowing for intensive agriculture, despite the fact that most of the work is done not by machinery, but by hand. The powerful and dangerous rivers that flow through the valleys have been harnessed to power grinding mills and to water the farm fields through the use of ingenious irrigation channels. Wheat, maize, grapes (generally used for wine), apples, apricots and walnuts are among the many foodstuffs grown in the area, along with surplus fodder used for feeding the livestock.

The climate is typical of high elevation regions without large bodies of water to regulate the temperature. The summers are mild and agreeable with average maximum temperatures between 23 and 27 °C (73 and 81 °F). Winters, on the other hand, can be very cold, with average minimum temperatures between 2 and 1 °C (36 and 34 °F). The average yearly precipitation is 700 to 800 mm (28 to 31 inches).[citation needed]

Genetic origins :

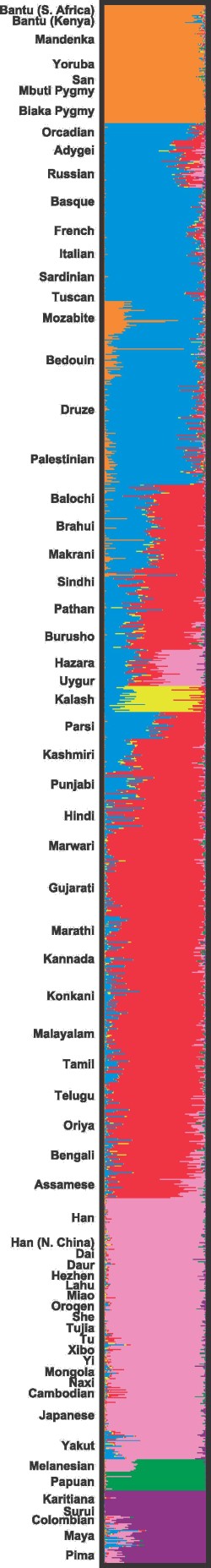

Rosenberg

et al. (2006) ran simulations dividing autosomal gene frequencies

in selected populations into a given number of clusters. For 7 or

more clusters, a cluster (yellow) appears which is nearly unique

to the Kalash. Smaller amounts of Kalash gene frequencies join clusters

associated with Europe and Middle East (blue) and with South Asia

(red).

Genetic analysis of Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) by Quintana-Murci et al. (2004) stated that "the western Eurasian presence in the Kalash population reaches a frequency of 100%" with the most prevalent mtDNA Haplogroups being U4 (34%), R0 (23%), U2e (16%), and J2 (9%). The study asserted that no East or South Asian lineages were detected and that the Kalash population is composed of western Eurasian lineages (as the associated lineages are rare or absent in the surrounding populations). The authors concluded that a western Eurasian origin for the Kalash is likely, in view of their maternal lineages.

A study of ASPM gene variants by Mekel-Bobrov et al. (2005) found that the Kalash people of Pakistan have among the highest rate of the newly evolved ASPM Haplogroup D, [clarification needed] at 60% occurrence of the approximately 6,000-year-old allele. The Kalash also have been shown to exhibit the exceedingly rare 19 allele value at autosomal marker D9S1120 at a frequency higher than the majority of other world populations which do have it.

A study by Rosenberg et al. (2006) employing genetic testing among the Kalash population concluded that they are a distinct (and perhaps aboriginal) population with only minor contributions from outside peoples. In one cluster analysis with (K = 7), the Kalash formed one cluster, the others being Africans, Europeans, Middle Easterners, South Asians, East Asians, Melanesians, and Native Americans.

A study by Li et al. (2008) with geneticists using more than 650,000 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) samples from the Human Genome Diversity Panel, found deep rooted lineages that could be distinguished in the Kalash. The results showed them clustered within the Central/South Asian populations at (K = 7). The study also showed the Kalash to be a separated group, having no membership within European populations.

Lazaridis et al. (2016) further notes that the demographic impact of steppe related populations on South Asia was substantial. According to the results, the Mala, a south Indian Dalit population with minimal Ancestral North Indian (ANI) along the 'Indian Cline' have nevertheless ~ 18 % steppe-related ancestry, showing the strong influence of ANI ancestry in all populations of India. The Kalash of Pakistan are inferred to have ~ 50 % steppe-related ancestry, with the rest being of Iranian Neolithic, Onge and Han.

According to Narasimhan et al. (2019), the Kalash were found to possess the highest ANI ancestry among the population samples analysed in the study.

European

descent hypothesis :

A study by Qasim Ayub, Massimo Mezzavilla, and Chris Tyler-Smith (2015) found no evidence of their claimed descent from soldiers of Alexander. The study, however, found that they shared a significant portion of genetic drift with MA-1, a 24,000-year-old Paleolithic Siberian hunter-gatherer fossil and the Yamnaya culture. The researchers thus believe they may be an ancient north-drifted Eurasian stock from which some of the modern European and Middle Eastern population also descends. Their mitochondrial lineages are predominantly from western Eurasia. Due to their uniqueness, the researchers believed that they were the earliest group to separate from the ancestral stock of the modern population of the Indian subcontinent estimated around 11,800 years ago.

The estimates by Qamar et al. of 20%–40% Greek admixture in the Kalash has been dismissed by Toomas Kivisild et al. (2003) stating that "some admixture models and programs that exist are not always adequate and realistic estimators of gene flow between populations ... this is particularly the case when markers are used that do not have enough restrictive power to determine the source populations ... or when there are more than two parental populations. In that case, a simplistic model using two parental populations would show a bias towards overestimating admixture". The study came to the conclusion that the Kalash population estimate by Qamar et al. "is unrealistic and is likely also driven by the low marker resolution that pooled southern and western Asian-specific Y-chromosome Haplogroup H together with European-specific Haplogroup I, into an uninformative polyphyletic cluster 2".

Discover magazine genetics blogger Razib Khan has repeatedly cited information indicating that the Kalash are part of the South Asian genetic continuum with no Macedonian ethnic admixture albeit shifted towards the Iranian people.

A study by Firasat et al. (2006) concluded that the Kalash lack typical Greek Haplogroups such as Haplogroup 21 (E-M35).

Economy

:

History

and social status :

Per their traditions, the Väi are refugees who fled from Kama to Waigal after the attack of the Ghazanavids. Per the traditions of the Gawâr, the Väi took the land from them and they migrated to the Kunar Valley. According to Strand, the Askun-speaking Kalash probably later migrated from Nakara in Laghman to lower Waigal. The Cima-nišei people took over their current settlements from the indigenous people. The people Vânt are refugees who fled from Tregam due to invasions. According to Kalsha traditions, some of the Väi who ritually hunted a golden bird every year at a place presently called Râmrâm in Kunar, settled there after failing to find their quarry and became the speakers of the Gawar-Bati language.

Shah Nadir Rais formed the Rais Dynasty of Chitral. The Rais carried out an invasion of Southern Chitral which was back then under Kalash rule. Kalash traditions record severe persecution and massacres at the hands of Rais. They were forced to flee the Chitral valley and those that remained while still practising their faith had to pay tribute in kind or with Corvée labour. The term "Kalash" was used to denote all the "Kafir" people in general; however, the Kalash of Chitral weren't considered to be "true Kafirs" by the Kati people who were interviewed about the term in 1835.

The Kalash were ruled by the Mehtar of Chitral from the 18th century onward. They have enjoyed a cordial relationship with the major ethnic group of Chitral, the Kho who are Sunni and Ismaili Muslims. The multi-ethnic and multi-religious State of Chitral ensured that the Kalash were able to live in peace and harmony and practice their culture and religion. The Kalash were protected by the Chitralis from Afghan Raids, who also generally did not allow Missionaries in Kalash. They allowed for the Kalash to look after their matters themselves. The Nuristani, their neighbours in the region of former Kafiristan west of the border, were converted, on pain of death, to Islam by Amir Abdur-Rahman of Afghanistan in the 1890s and their land was renamed.

Prior to that event, the people of Kafiristan had paid tribute to the Mehtar of Chitral and accepted his suzerainty. This came to an end with the Durand Agreement when Kafiristan fell under the Afghan sphere of Influence. [citation needed] Prior to the 1940s the Kalash had five valleys, the current three as well as Jinjeret kuh and Urtsun to the south. The last Kalash person in Jinjeret kuh was Mukadar, who passing away in the early 1940s found himself with no one to perform the old rites. The people of Birir valley just north of Jinjeret came to the rescue with a moving funeral procession that is still remembered fondly by the valleys now converted Kalash, firing guns and beating drums as they made their way up the valley to celebrate his passing according to the old custom. The Kalash of Urtsun valley had a culture with a large Kam influence from the Bashgul Valley. It was known for its shrines to Waren and Imro—the Urtsun version of Dezau—which were visited and photographed by Georg Morgenstierne in 1929 and were built in the Bashgul Valley style unlike those of other Kalash valleys . The last Shaman - was one Azermalik who had been the Dehar when George Scott Robertson visited in the 1890s. His daughter Mranzi who was still alive into the 1980s was the last Urtsun valley Kalash practising the old religion. She had married into the Birir Valley Kalash and left the valley in the late 1930s when the valley had converted to Islam. Unlike the Kalash of the other valleys the women of Urtsun did not wear the Kup'as headress but had their own P'acek - headress worn at casual times and the famous horned headress of the Bashgul valley which was worn at times of ritual and dance. Other theories considered about their origin is that they are descendants of foreign peoples, the Gandhari people and the old Indian population of Eastern Afghanistan. George Scott Robertson put forth the view that the dominant Kafir races like the Wai were refugees who fled to the region from invading fanatical Muslims. The Kafirs are historically recorded for the first time in 1339.

Being a very small minority in a Muslim region, the Kalash have increasingly been targeted by some proselytising Muslims. Some Muslims have encouraged the Kalash people to read the Koran so that they would convert to Islam. The challenges of modernity and the role of outsiders and NGOs in changing the environment of the Kalash valleys have also been mentioned as real threats for the Kalash.

During the 1970s, local Muslims and militants tormented the Kalash because of the difference in religion and multiple Taliban attacks on the tribe lead to the death of many, their numbers shrank to just two thousand.

However, protection from the government led to a decrease in violence by locals, a decrease in Taliban attacks, and a great reduction in the child mortality rate. The last two decades saw a rise in numbers.

In recent times the Kalash and Ismailis have been threatened with death by the Taliban, the threats caused outrage and horrified citizens [failed verification] throughout Pakistan and the Pakistani military responded by fortifying the security around Kalash villages, the Supreme Court also took judicial intervention to protect the Kalash under both the ethnic minorities clause of the constitution and Pakistan's Sharia law penal code which declares it illegal for Muslims to criticise and attack other religions on grounds of personal belief. The Supreme Court termed the Taliban's threats against Islamic teachings. Imran Khan condemned the forced conversions threat as un-Islamic.

In 2017, Wazir Zada became the first Kalash man to win a seat in the Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa Provicional assembly. He became the member of the Provincial Assembly (PA) on a minority reserved seat.

In November 2019, the Kalash people were visited by HRH the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge, as part of their Pakistan tour and they saw a traditional dance performance there.

Appearances

in popular culture :

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

;_Tahsin_Shah_04.jpg)

;_Tahsin_Shah_01.jpg)