| HOTAN

Tuanjie Square

Location in Xinjiang Hotan (also known as Gosthana, Gaustana, Godana, Godaniya, Khotan, Hetian, Hotien) is a major oasis town in southwestern Xinjiang, an autonomous region in Western China. The city proper of Hotan broke off from the larger Hotan County to become an administrative area in its own right in August 1984. It is the seat of Hotan Prefecture.

With a population of 322,300 (2010 census), Hotan is situated in the Tarim Basin some 1,500 kilometres (930 mi) southwest of the regional capital, Ürümqi. It lies just north of the Kunlun Mountains, which are crossed by the Sanju, Hindutash and Ilchi passes. The town, located southeast of Yarkant County and populated almost exclusively by Uyghurs, is a minor agricultural center. An important station on the southern branch of the historic Silk Road, Hotan has always depended on two strong rivers—the Karakash River and the White Jade River to provide the water needed to survive on the southwestern edge of the vast Taklamakan Desert. The White Jade River still provides water and irrigation for the town and oasis.

Etymology

:

Gosthana/Gausthana/Gaustana/Godana/Godaniya translates to "land of cows" in Sanskrit. In Chinese, the same name is written as Yu-t'ien, pronounced as Gu-dana. The pronunciation changed over the years to Kho-tan. In the 7th century, Xuanzang tried to reverse interpret it in Sanskrit as Kustana. However, the Tibetans continue to call it Gosthana, which also carries the meaning of "land of cows".

History :

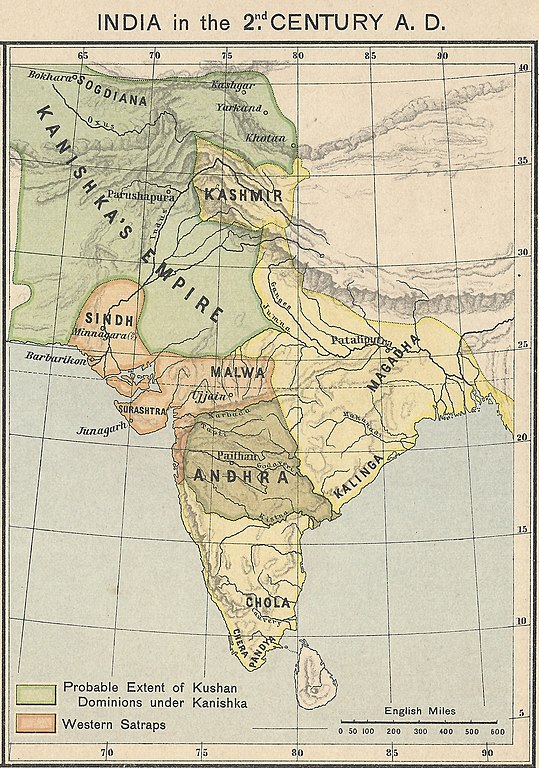

Bronze coin of Vima Kadphises found in Khotan The oasis of Hotan is strategically located at the junction of the southern (and most ancient) branch of the Silk Road joining China and the West with one of the main routes from ancient India and Tibet to Central Asia and distant China. It provided a convenient meeting place where not only goods, but technologies, philosophies, and religions were transmitted from one culture to another.

Tocharians lived in this region over 2000 years ago. Several of the Tarim mummies were found in the region. At Sampul, east of the city of Hotan, there is an extensive series of cemeteries scattered over an area about 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) wide and 23 km (14 mi) long. The excavated sites range from about 300 BCE to 100 CE. The excavated graves have produced a number of fabrics of felt, wool, silk and cotton and even a fine bit of tapestry, the Sampul tapestry, showing the face of Caucasoid man which was made of threads of 24 shades of colour. The tapestry had been cut up and fashioned into trousers worn by one of the deceased. An Anthropological study of 56 individuals showed a primarily Caucasoid population. DNA testing on the mummies found in the Tarim basin showed that they were an admixture of Western Europeans and East Asian.

Khotan Melikawat ruins There is a relative abundance of information on Hotan readily available for study. The main historical sources are to be found in the Chinese histories (particularly detailed during the Han and early Tang dynasties) when China was interested in control of the Western Regions, the accounts of several Chinese pilgrim monks, a few Buddhist histories of Hotan that have survived in Classical Tibetan and a large number of documents in the Iranian Saka language and other languages discovered, for the most part, early this century at various sites in the Tarim Basin and from the hidden library at the Mogao Caves near Dunhuang.

Buddhist

Khotan :

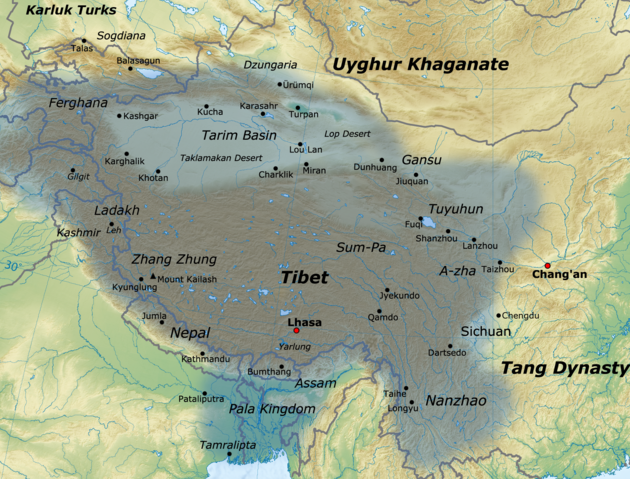

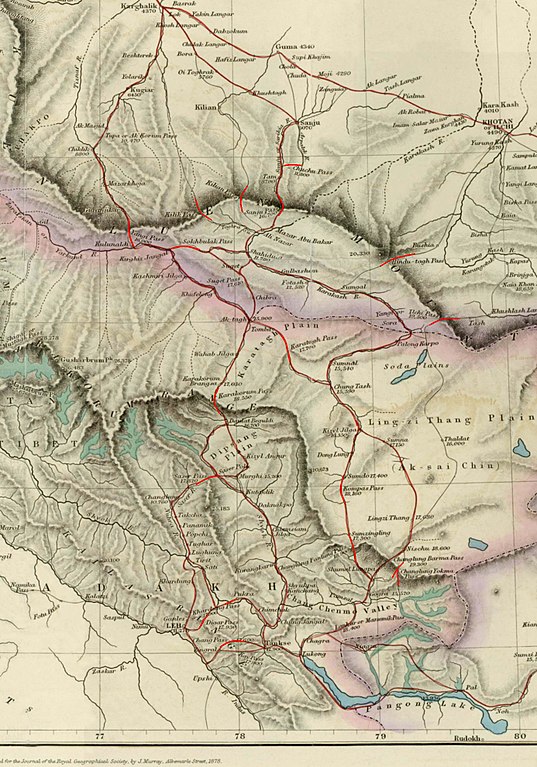

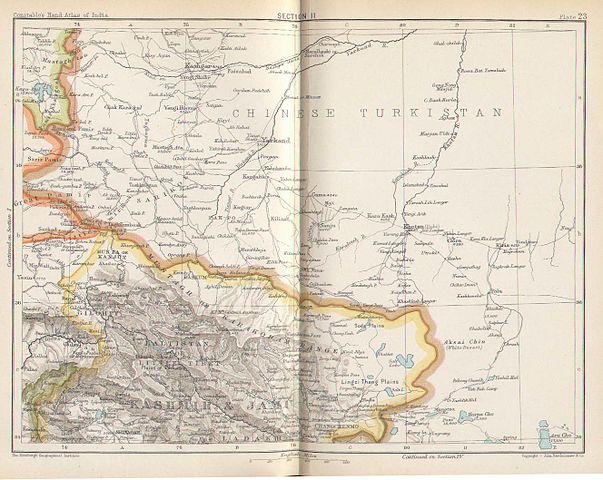

Khotan in the Tibetan Empire

Map

of Central Asia (1878) showing Khotan (near top right corner) and

the Sanju Pass, Hindutash, and Ilchi passes through the Kunlun Mountains

to Leh, Ladakh. The previous border of the British Indian Empire

is shown in the two-toned purple and pink band.

In the 10th century, Khotan began a struggle with the Kara-Khanid Khanate, a Turkic state. The Kara-Khanid ruler, Sultan Satuq Bughra Khan, had converted to Islam:

Satuq's son, Musa, began to put pressure on Khotan in the mid-10th century, and sometime before 1006 Yusuf Qadir Khan of Kashgar besieged and took the city. This conquest of Buddhist Khotan by the Muslim Turks—about which there are many colourful legends—marked another watershed in the Islamicisation and Turkicisation of the Tarim Basin, and an end to local autonomy of this southern Tarim city state.

Some Khotanese Buddhist works were unearthed.

The rulers of Khotan were aware of the menace they faced since they arranged for the Mogao grottoes to paint a growing number of divine figures along with themselves. Halfway in the 10th century Khotan came under attack by the Qarakhanid ruler Musa, and in what proved to be a pivotal moment in the Turkification and Islamification of the Tarim Basin, the Karakhanid leader Yusuf Qadir Khan conquered Khotan around 1006.

Islamic Khotan :

A mosque in Hotan Yusuf Qadr Khan was a brother or cousin of the Muslim ruler of Kashgar and Balasagun, Khotan lost its independence and between 1006 and 1165, became part of the Kara-Khanid Khanate. Later it fell to the Kara-Khitan Khanate, after which it was ruled by the Mongols. When Marco Polo visited Khotan in the 13th century, he noted that the people were all Muslim. He wrote that:

Khotan was "a province eight days’ journey in extent, which is subject to the Great Khan. The inhabitants all worship Mahomet. It has cities and towns in plenty, of which the most splendid, and the capital of the province, bears the same name as that of the province…It is amply stocked with the means of life. Cotton grows here in plenty. It has vineyards, estates and orchards in plenty. The people live by trade and industry; they are not at all warlike".

19th century :

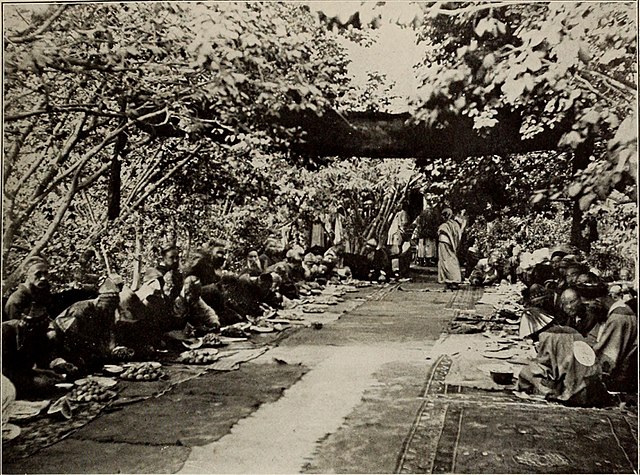

Amban's Guests festing on terrace leading in Nar-Bagh The town suffered severely during the Dungan Revolt (1862–77) against the Qing dynasty and again a few years later when Yaqub Beg of Kashgar made himself master of Kashgaria, ruling the newly founded Turkic state known at the time as Yettishar.

Post-Qing :

This section does not cite any sources.

Chinese troops at Khotan, 1915 Qing imperial authority collapsed in 1912. During the Republican era in China, warlords and local ethnic self-determination movements wrestled over control of Xinjiang. Abdullah Bughra, Nur Ahmad Jan Bughra, and Muhammad Amin Bughra declared themselves Emirs of Khotan during the Kumul Rebellion. Tunganistan was an independent administered region in the southern part of Xinjiang from 1934 to 1937. The territory included the oases of the southern Tarim Basin; the centre of the region was Khotan. Beginning with the Islamic rebellion in 1937, Hotan and the rest of the province came under the control of warlord Sheng Shicai. Sheng was later ousted by the Kuomintang.

People's

Republic of China :

In 1983/4, the urban area of Hotan was administratively split from the larger Hotan County, and from then on governed as a county-level city.

On July 11, 2006, the townships of Jiya and Yurungqash (Yulongkashi) in Lop County and Tusalla (Tushala) in Hotan County were transferred to Hotan City.

Following the July 2009 Ürümqi riots, ethnic tensions rose in Xinjiang and in Hotan in particular. As a result, the city has seen occasional bouts of violence. In June 2011, Hotan opened its first passenger-train service to Kashgar, which was established as a special economic zone following the riots. In July of the same year, a bomb and knife attack occurred on the city's central thoroughfare. In June 2011, authorities in Hotan Prefecture sentenced Uyghur Muslim Hebibullah Ibrahim to ten years imprisonment for selling "illegal religious materials". In June 2012, Tianjin Airlines Flight 7554 was hijacked en route from Hotan to Ürümqi.

In a report from the Uyghur American Association, in June 2012, notice was said to be given that police planned to undertake a search of every residence in Gujanbagh (Gujiangbage), Hotan. Hotan is the last municipality in Xinjiang with a majority Ugyhur presence in the core of the city. The UAA viewed this as an attempt to systematically intimidate the Uyghur population in Hotan.[better source needed]

Sultanim Cemetery (37°07'02 N 79°56'04 E) was the central Uyghur historical graveyard with generations of burials and was the most sacred shrine in Hotan city. Between 2018 and 2019, the cemetery was demolished and made into a parking lot.

Geography and climate :

Collecting jade in the White Jade River near Hotan in 2011 Hotan has a temperate zone, cold desert climate (Köppen BWk), with a mean annual total of only 36.5 millimetres (1.44 in) of precipitation falling on 17.3 days of the year. Due to its southerly location in Xinjiang just north of the Kunlun Mountains, during winter it is one of the warmest locations in the region, with average high temperatures remaining above freezing throughout the year. The monthly 24-hour average temperature ranges from -3.9 °C (25.0 °F) in January to 25.8 °C (78.4 °F) in July, and the annual mean is 13.03 °C (55.5 °F). The diurnal temperature variation is not large for a desert, averaging 11.8 °C (21.2 °F) annually. Although no month averages less than half of possible sunshine, the city only receives 2,587 hours of bright sunshine annually, which is on the low end for Xinjiang; monthly percent possible sunshine ranges from 50% in March to 75% in October.

Administrative divisions :

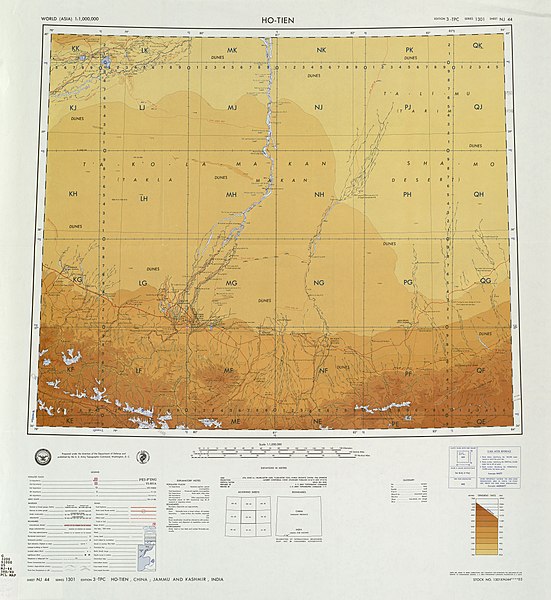

Map of Hotan (labeled as HO-TIEN (HO-T'IEN) (KHOTAN)) and surrounding region from the International Map of the World (USATC, 1971) The city includes four subdistricts, three towns, five townships and two other areas :

Subdistricts :

•

Nurbag Subdistrict

(Nu'erbage), Gujanbagh Subdistrict (Gujiangbage), Gulbagh Subdistrict

(Gulebage), Na'erbage Subdistrict.

•

Laskuy (Lasikui,

Lasqi), Yurungqash (Yulongkashi), Tusalla (Tushala, formerly)

•

Shorbagh Township

(Xiao'erbage), Ilchi Township (Yiliqi), Gujanbagh Township (Gujiangbage),

Jiya Township, Aqchal Township (Akeqiale)

•

Beijing Industrial

Park, Hotan City Jinghe Logistics Park

In 1940, Owen Lattimore quoted the population of Khotan to be estimated as 26,000.

In 1998 the urban population was recorded at 154,352, 83% of which were Uyghurs, and 17% were Han Chinese.

In 1999, 83.01% of the population was Uyghur and 16.57% of the population was Han Chinese.

In the 2000 census, the population was recorded as 186,123. In the 2010 census figure, the figure had risen to 322,300. The increase in population is partly due to boundary changes.

Transportation :

Locals at a busy Hotan market

Air :

Road

:

Rail

:

Buses

:

Economy :

Light coloured or "Mutton fat" jade for sale at Hotan Jade Market

Silk weaving in Hotan As of 1885, there was about 100,000 acres (662,334 mu) of cultivated land in Khotan.

Nephrite

jade :

Fabrics

and carpets :

Ancient Chinese-Khotanese relations were so close that the oasis emerged as one of the earliest centres of silk manufacture outside China. There are good reasons to believe that the silk-producing industry flourished in Hotan as early as the 5th century. According to one story, a Chinese princess given in marriage to a Khotan prince brought to the oasis the secret of silk-manufacture, "hiding silkworms in her hair as part of her dowry", probably in the first half of the 1st century CE. It was from Khotan that the eggs of silkworms were smuggled to Iran, reaching Justinian I's Constantinople in 551. Silk production is still a major industry employing more than a thousand workers and producing some 150 million metres of silk annually. Silk weaving by Uyghur women is a thriving cottage industry, some of it produced using traditional methods. Hotan Silk Factory is one of the notable silk producers in Hotan.

Atlas is the fabric used for traditional Uyghur clothing worn by Uyghur women. It is soft, light and graceful tie-dyed silk fabric. It comes various colours, the brighter and rich colours are for small children to young ladies. The gray and dark colours are for elderly women.

The oldest piece of kilim which we have any knowledge was obtained by the archaeological explorer Aurel Stein; a fragment from an ancient settlement near Hotan, which was buried by sand drifts about the fourth century CE. The weave is almost identical with that of modern kilims.

Hotanese pile carpets are still highly prized and form an important export.

Notable

persons :

Market in Hotan

Uyghur people at Sunday market

Carpet weaving in Hotan

Silk weaving in Hotan

Entrance to the Hotan Cultural Museum

Local jade displayed in the Hotan Cultural Museum lobby

Map of the region including Khotan (Ilchi) (1893)

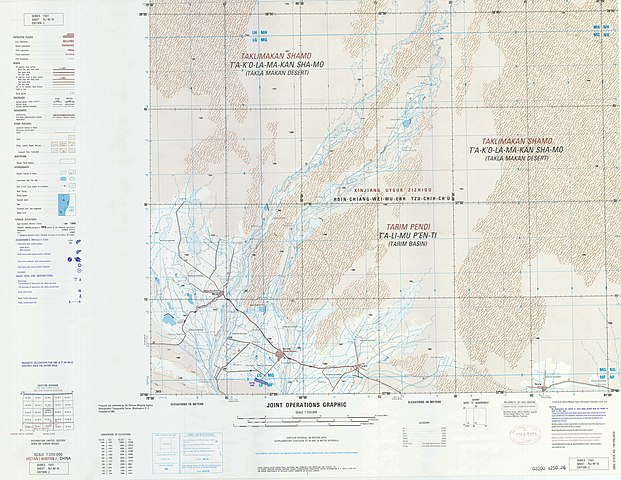

Map including Hotan (Ho-t'ien, Khotan) (DMA, 1983) Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |