| KUSHAN EMPIRE Kushan Empire

30 - 375

Status : Nomadic empire

Capital : Bagram (Kapisi), Peshawar (Purushpur), Taxila (Takshshila), Mathura (Mathura)

Common languages : Greek (official until ca. 127), Bactrian (official from ca. 127), Sanskrit

Religion : Buddhism, Hinduism, Zoroastrianism

Government : Monarchy

Emperor

• 30 - 80 : Kujula Kadphises

• 350 - 375 : Kipunad

Historical era : Classical Antiquity

• Kujul Kadphises unites Yuezhi tribes into a confederation : 30

• Subjugated by the Sasanians, Guptas, and Hepthalites : 375

Area

200 est. : 2,000,000 km2 (770,000 sq mi)

200 est. : 2,500,000 km2 (970,000 sq mi)

Currency : Kushan drachma

Preceded by

Indo-Greek Kingdom

Indo-Parthian Kingdom

Indo-Scythians

Succeeded by

Sasanian Empire

Gupta Empire

Nagas of Padmavati

Kidarites

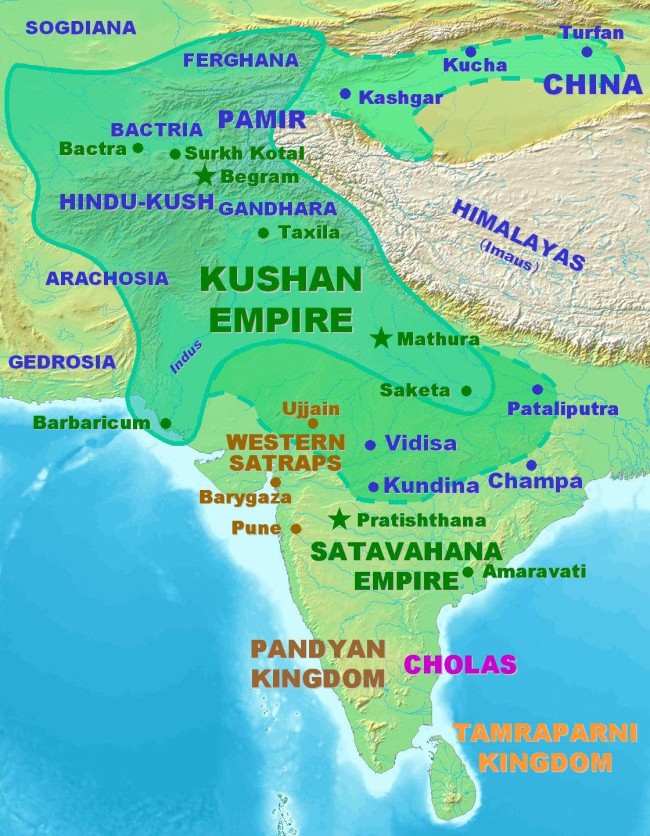

A map of India in the 2nd century CE showing the extent of the Kushan Empire (in yellow) during the reign of Kanishk. Most historians consider the empire to have variously extended as far east as the middle Ganges plain, to Varanasi on the confluence of the Ganges and the Jamuna, or probably even Pataliputra.

The Kushan Empire (Bactrian: Kushano; Sanskrit: Kushan Rajavansh, BHS: Gushan vansh; Parthian: Kušan-xša0r; Sanskrit: Ku-sha-na (Late Brahmi script), Kusana Samrajya; BHS: Gusana-vamsa) was a syncretic empire, formed by the Yuezhi, in the Bactrian territories in the early 1st century. It spread to encompass much of Afghanistan, and then the northern parts of the Indian subcontinent at least as far as Saket and Sarnath near Varanasi (Benares), where inscriptions have been found dating to the era of the Kushan Emperor Kanishk the Great. Emperor Kanishk and the Kushans in general were great patrons of Buddhism, as well as Zoroastrianism. They played an important role in the establishment of Buddhism in the Indian subcontinent and its spread to Central Asia and China.

The Kushans were most probably one of five branches of the Yuezhi confederation, an Indo-European nomadic people of possible Tocharian origin, who migrated from northwestern China (Xinjiang and Gansu) and settled in ancient Bactria.

The Kushans possibly used the Greek language initially for administrative purposes, but soon began to use Bactrian language. Kanishk sent his armies north of the Karakoram mountains. A direct road from Gandhar to China remained under Kushan control for more than a century, encouraging travel across the Karakoram and facilitating the spread of Mahayan Buddhism to China.

The Kushan dynasty had diplomatic contacts with the Roman Empire, Sasanian Persia, the Aksumite Empire and the Han dynasty of China. The Kushan Empire was at the center of trade relations between the Roman Empire and China: according to Alain Daniélou, "for a time, the Kushan Empire was the centerpoint of the major civilizations". While much philosophy, art, and science was created within its borders, the only textual record of the empire's history today comes from inscriptions and accounts in other languages, particularly Chinese.

The Kushan empire fragmented into semi-independent kingdoms in the 3rd century AD, which fell to the Sasanians invading from the west, establishing the Kushano-Sasanian Kingdom in the areas of Sogdian, Bactria and Gandhar. In the 4th century, the Guptas, an Indian dynasty also pressed from the east. The last of the Kushan and Kushano-Sasanian kingdoms were eventually overwhelmed by invaders from the north, known as the Kidarites, and then the Hephthalites.

Origins :

Yuezhi nobleman over a fire altar. Noin-Ula Chinese sources describe the Guishuang, i.e. the Kushans, as one of the five aristocratic tribes of the Yuezhi. There is scholarly consensus that the Yuezhi were a people of Indo-European origin. A specifically Tocharian origin of the Yuezhi is often suggested. An Iranian, specifically Saka, origin, also has some support among scholars. Others suggest that the Yuezhi might have originally been a nomadic Iranian people, who were then partially assimilated by settled Tocharians, thus containing both Iranian and Tocharian elements.

The Yuezhi were described in the Records of the Great Historian and the Book of Han as living in the grasslands of eastern Xinjiang and northwestern part of Gansu, in the northwest of modern-day China, until their King was beheaded by the Xiongnu who were also at war with China, which eventually forced them to migrate west in 176–160 BCE. The five tribes constituting the Yuezhi are known in Chinese history as Xiumì, Guìshuang, Shuangmi, Xìdùn, and Dumì.

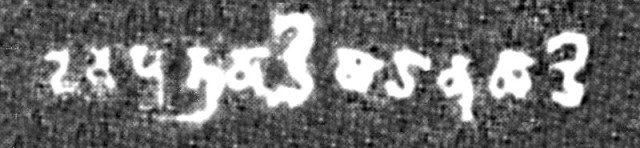

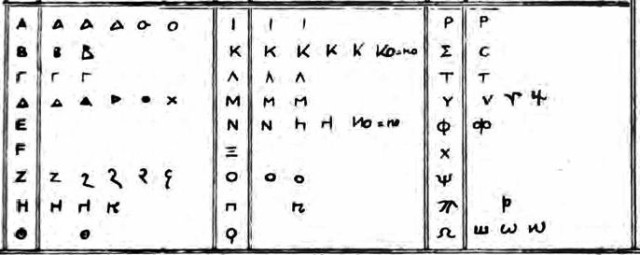

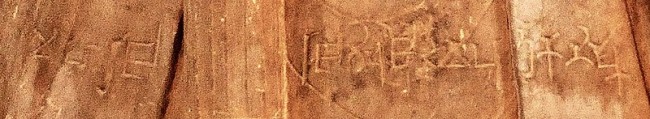

The ethnonym "KObbANOV" (Koshshanoy, "Kushans") in Greek alphabet (with the addition of the letter b, "Sh") on a coin of the first known Kushan ruler Heraios (1st century CE) The Yuezhi reached the Hellenic kingdom of Greco-Bactria (in northern Afghanistan and Uzbekistan) around 135 BC. The displaced Greek dynasties resettled to the southeast in areas of the Hindu Kush and the Indus basin (in present-day Afghanistan and Pakistan), occupying the western part of the Indo-Greek Kingdom.

In India, Kushan emperors regularly used the dynastic name ("Koshano") on their coinage. Several inscriptions in Sanskrit in the Brahmi script, such as the Mathura inscription of the statue of Vim Kadphises, refer to the Kushan Emperor as Ku-sha-na ("Kushan"). Some later Indian literary sources referred to the Kushans as Turushk, a name which in later Sanskrit sources was confused with Turk, "probably due to the fact that Tukharistan passed into the hands of the western Turks in the seventh century". Yet, according to Wink, "nowadays no historian considers them to be Turkish-Mongoloid or 'Hun', although there is no doubt about their Central-Asian origin."

Early Kushans : Kushan portraits

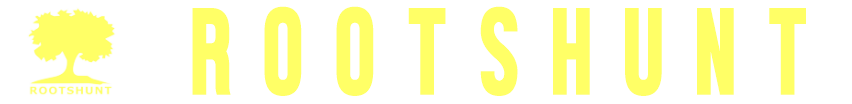

Head of a Yuezhi prince (Khalchayan palace, Uzbekistan)

The first king to call himself "Kushan" on his coinage: Heraios (1 – 30 CE)

Kushan devotee (2nd century CE). Metropolitan Museum of Art (detail)

Portrait of Kushan emperor Vim Kadphises, 100 - 127 CE Some traces remain of the presence of the Kushans in the area of Bactria and Sogdiana in the 2nd-1st century BCE, where they had displaced the Sakas, who moved further south. Archaeological structures are known in Takht-i Sangin, Surkh Kotal (a monumental temple), and in the palace of Khalchayan. On the ruins of ancient Hellenistic cities such as Ai-Khanoum, the Kushans are known to have built fortresses. Various sculptures and friezes from this period are known, representing horse-riding archers, and, significantly, men such as the Kushan prince of Khalchayan with artificially deformed skulls, a practice well attested in nomadic Central Asia. Some of the Khalchayan sculptural scenes are also thought to depict the Kushans fighting against the Sakas. In these portrayals, the Yuezhis are shown with a majestic demeanour, whereas the Sakas are typically represented with side-wiskers, and more or less grotesque facial expressions.

The Chinese first referred to these people as the Yuezhi and said they established the Kushan Empire, although the relationship between the Yuezhi and the Kushans is still unclear. Ban Gu's Book of Han tells us the Kushans (Kuei-shuang) divided up Bactria in 128 BCE. Fan Ye's Book of Later Han "relates how the chief of the Kushans, Ch'iu-shiu-ch'ueh (the Kujula Kadphises of coins), founded by means of the submission of the other Yueh-chih clans the Kushan Empire."

The earliest documented ruler, and the first one to proclaim himself as a Kushan ruler, was Heraios. He calls himself a "tyrant" in Greek on his coins, and also exhibits skull deformation. He may have been an ally of the Greeks, and he shared the same style of coinage. Heraios may have been the father of the first Kushan emperor Kujul Kadphises.

The Chinese Book of Later Han chronicles then gives an account of the formation of the Kushan empire based on a report made by the Chinese general Ban Yong to the Chinese Emperor c. 125 AD:

More than a hundred years later [than the conquest of Bactria by the Da Yuezhi], the prince [xihou] of Guishuang (Badakhshan) established himself as king, and his dynasty was called that of the Guishuang (Kushan) King. He invaded Anxi (Indo-Parthia), and took the Gaofu (Kabul) region. He also defeated the whole of the kingdoms of Puda (Paktiya) and Jibin (Kapish and Gandhar). Qiujiuque (Kujula Kadphises) was more than eighty years old when he died. His son, Yangaozhen [probably Vem Tahk (tu) or, possibly, his brother Sadaskana ], became king in his place. He defeated Tianzhu [North-western India] and installed Generals to supervise and lead it. The Yuezhi then became extremely rich. All the kingdoms call [their king] the Guishuang [Kushan] king, but the Han call them by their original name, Da Yuezhi.

—

Book of Later Han.

Early gold coin of Kanishk I with Greek language legend and Hellenistic divinity Helios. (c. 120 AD)

Obverse : Kanishk standing, clad in heavy Kushan

coat and long boots, flames emanating from shoulders, holding a

standard in his left hand, and making a sacrifice over an altar.

Greek legend :

Greek alphabet (narrow columns) with Kushan script (wide columns) In the 1st century BCE, the Guishuang gained prominence over the other Yuezhi tribes, and welded them into a tight confederation under yabgu (Commander) Kujula Kadphises. The name Guishuang was adopted in the West and modified into Kushan to designate the confederation, although the Chinese continued to call them Yuezhi.

Gradually wresting control of the area from the Scythian tribes, the Kushans expanded south into the region traditionally known as Gandhar (an area primarily in Pakistan's Pothowar and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa region) and established twin capitals in Begram and Peshawar, then known as Kapisa and Pushklavati respectively.

The Kushans adopted elements of the Hellenistic culture of Bactria. They adopted the Greek alphabet to suit their own language (with the additional development of the letter Þ "sh", as in "Kushan") and soon began minting coinage on the Greek model. On their coins they used Greek language legends combined with Pali legends (in the Kharoshthi script), until the first few years of the reign of Kanishk. After the middle of Kanishk's reign, they used Kushan language legends (in an adapted Greek script), combined with legends in Greek (Greek script) and legends in Prakrit (Kharoshthi script).

The Kushans "adopted many local beliefs and customs, including Zoroastrianism and the two rising religions in the region, the Greek cults and Buddhism". From the time of Vim Takto, many Kushans started adopting aspects of Buddhist culture, and like the Egyptians, they absorbed the strong remnants of the Greek culture of the Hellenistic Kingdoms, becoming at least partly Hellenised. The great Kushan emperor Vim Kadphises may have embraced Shaivism (a sect of Hinduism), as surmised by coins minted during the period. The following Kushan emperors represented a wide variety of faiths including Buddhism, Zoroastrianism and Shaivism.

The rule of the Kushans linked the seagoing trade of the Indian Ocean with the commerce of the Silk Road through the long-civilized Indus Valley. At the height of the dynasty, the Kushans loosely ruled a territory that extended to the Aral Sea through present-day Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan into northern India.

The loose unity and comparative peace of such a vast expanse encouraged long-distance trade, brought Chinese silks to Rome, and created strings of flourishing urban centers.

Territorial expansion :

Kushan

territories (full line) and maximum extent of Kushan control under

Kanishk the Great. The extent of Kushan control is notably documented

in the Rabatak inscription. The northern expansion into the Tarim

Basin is mainly suggested by coin finds and Chinese chronicles.

Other areas of probable rule include Khwarezm and its capital city of Toprak-Kal, Kausambi (excavations of Allahabad University), Sanchi and Sarnath (inscriptions with names and dates of Kushan kings), Malwa and Maharashtra, and Odisha (imitation of Kushan coins, and large Kushan hoards).

Map showing the four empires of Eurasia in the 2nd century CE. "For a time, the Kushan Empire was the centerpoint of the major civilizations" Kushan invasions in the 1st century CE had been given as an explanation for the migration of Indians from the Indian Subcontinent toward Southeast Asia according to proponents of a Greater India theory by 20th-century Indian nationalists. However, there is no evidence to support this hypothesis.

The recently discovered Rabatak inscription confirms the account of the Hou Hanshu, Weilüe, and inscriptions dated early in the Kanishk era (incept probably 127 CE), that large Kushan dominions expanded into the heartland of northern India in the early 2nd century CE. Lines 4 to 7 of the inscription describe the cities which were under the rule of Kanishk, among which six names are identifiable: Ujjain, Kundina, Saket, Kausambi, Pataliputra, and Champa (although the text is not clear whether Champa was a possession of Kanishk or just beyond it). The Buddhist text Sridharmapitkanidansutra—known via a Chinese translation made in 472 CE—refers to the conquest of Pataliputra by Kanishk. A 2nd century stone inscription by a Great Satrap named Rupiamma was discovered in Pauni, south of the Narmada river, suggesting that Kushan control extended this far south, although this could alternatively have been controlled by the Western Satraps.

Eastern reach as far as Bengal: Samatat coinage of king Vir Jadamarah,

in imitation of the Kushan coinage of Kanishk I. The text of the

legend is a meaningless imitation. Bengal, circa 2nd-3rd century

CE.

In the West, the Kushan state covered the Parat state of Balochistan, western Pakistan, Afghanistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan. Turkmenistan was known for the Kushan Buddhist city of Merv.

Northward, in the 2nd century CE, the Kushans under Kanishk made various forays into the Tarim Basin, where they had various contacts with the Chinese. Kanishk held areas of the Tarim Basin apparently corresponding to the ancient regions held by the Yüeh-zhi, the possible ancestors of the Kushan. There was Kushan influence on coinage in Kashgar, Yarkand, and Khotan. According to Chinese chronicles, the Kushans (referred to as Da Yuezhi in Chinese sources) requested, but were denied, a Han princess, even though they had sent presents to the Chinese court. In retaliation, they marched on Ban Chao in 90 CE with a force of 70,000 but were defeated by the smaller Chinese force. Chinese chronicles relate battles between the Kushans and the Chinese general Ban Chao. The Yuezhi retreated and paid tribute to the Chinese Empire. The regions of the Tarim Basin were all ultimately conquered by Ban Chao. Later, during the Yuánchu period (114–120 CE), the Kushans sent a military force to install Chenpan, who had been a hostage among them, as king of Kashgar.

Main

Kushan rulers :

Kujula

Kadphises (c. 30 – c. 80) :

...the prince [elavoor] of Guishuang, named thilac [Kujul Kadphises], attacked and exterminated the four other xihou. He established himself as king, and his dynasty was called that of the Guishuang [Kushan] King. He invaded Anxi [Indo-Parthia] and took the Gaofu [Kabul] region. He also defeated the whole of the kingdoms of Puda [Paktiya] and Jibin [Kapish and Gandhar]. Qiujiuque [Kujul Kadphises] was more than eighty years old when he died."

—

Hou Hanshu

Kujul issued an extensive series of coins and fathered at least two sons, Sadaskan (who is known from only two inscriptions, especially the Rabatak inscription, and apparently never ruled), and seemingly Vim Takto.

Kujula Kadphises was the great-grandfather of Kanishk.

Vim

Taktu or Sadashkana (c. 80 - c. 95) :

"His son, Yangaozhen [probably Vem Tahk (tu) or, possibly, his brother Sada?ka?a], became king in his place. He defeated Tianzhu [North-western India] and installed Generals to supervise and lead it. The Yuezhi then became extremely rich. All the kingdoms call [their king] the Guishuang [Kushan] king, but the Han call them by their original name, Da Yuezhi."

—

Hou Hanshu

Vim Kadphises added to the Kushan territory by his conquests in Bactria. He issued an extensive series of coins and inscriptions. He issued gold coins in addition to the existing copper and silver coinage.

Kanishk I (c. 127 - c. 150) :

Mathura statue of Kanishk

Statue of Kanishk in long coat and boots, holding a mace and a sword, in the Mathura Museum. An inscription runs along the bottom of the coat.

The

inscription is in middle Brahmi script

Maharaja Rajadhiraj Devputra Kanisk

"The

Great King, King of Kings, Son of God, Kanishk".

Mathura

art, Mathura Museum

The rule of Kanishk the Great, fourth Kushan king, lasted for about 23 years from c. 127 CE. Upon his accession, Kanishk ruled a huge territory (virtually all of northern India), south to Ujjain and Kundin and east beyond Pataliputra, according to the Rabatak inscription:

In the year one, it has been proclaimed unto India, unto the whole realm of the governing class, including Koonadeano (Kaundiny, Kundina) and the city of Ozeno (Ozene, Ujjain) and the city of Zaged (Saket) and the city of Kozambo (Kausambi) and the city of Palabotro (Pataliputra) and as far as the city of Ziri-tambo (Sri-Champa), whatever rulers and other important persons (they might have) he had submitted to (his) will, and he had submitted all India to (his) will.

—

Rabatak inscription, Lines 4–8

The Kushans also had a summer capital in Bagram (then known as Kapisa), where the "Begram Treasure", comprising works of art from Greece to China, has been found. According to the Rabatak inscription, Kanishk was the son of Vim Kadphises, the grandson of Sadashkan, and the great-grandson of Kujul Kadphises. Kanishk's era is now generally accepted to have begun in 127 on the basis of Harry Falk's ground-breaking research. Kanishk's era was used as a calendar reference by the Kushans for about a century, until the decline of the Kushan realm.

Huvishk

(c. 150 - c. 180) :

Vasudev

I (c. 190 – c. 230) :

Vasishk (c. 247 - c. 267) :

Vasishk was a Kushan emperor who seems to have had a 20-year reign following Kanishk II. His rule is recorded at Mathura, in Gandhar and as far south as Sanchi (near Vidisa), where several inscriptions in his name have been found, dated to the year 22 (the Sanchi inscription of "Vaksushan" – i.e., Vasishk Kushana) and year 28 (the Sanchi inscription of Vasask– i.e., Vasishk) of a possible second Kanishk era.

Little

Kushans (270 - 350 CE) :

Kushan deities :

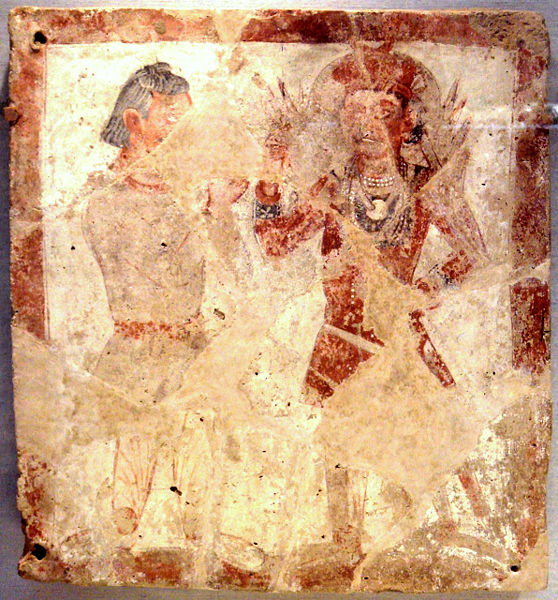

Kumar / Kartikey with a Kushan devotee, 2nd century CE

Kushan prince, said to be Huvishk, making a donation to a Boddhisattva

Shiv Ling worshipped by Kushan devotees, circa 2nd century CE The Kushan religious pantheon is extremely varied, as revealed by their coins that were made in gold, silver, and copper. These coins contained more than thirty different gods, belonging mainly to their own Iranian, as well as Greek and Indian worlds as well. Kushan coins had images of Kushan Kings, Buddh, and figures from the Indo-Aryan and Iranian pantheons. Greek deities, with Greek names are represented on early coins. During Kanishk's reign, the language of the coinage changes to Bactrian (though it remained in Greek script for all kings). After Huvishk, only two divinities appear on the coins: Ardoxsho and Oesho.

The Iranian entities depicted on coinage include :

•

Ardoxsho, Ashi

Vanghuhi

•

Helios, Hephaistos,

Selene, Anemos. Further, the coins of Huvishk also portray the demi-god

erakilo Heracles, and the Egyptian god sarapo Sarapis

•

Boddo, Buddh

Images of Kushan worshippers

Kushan worshipper with Zeus / Serapis / Ohrmazd, Bactria, 3rd century CE

Kushan worshipper with Pharro, Bactria, 3rd century AD

Kushan worshipper with Shiv / Oesho, Bactria, 3rd century CE

Shiv-Oesho wall painting with fragment of a worshipper, Bactria, 3rd century CE Deities on Kushan coinage and seals

Mahasen on a coin of Huvishk

Four-faced Oesho

Rishti

Manaobago

Pharro

Ardochsho

Oesho or Shiv

Oesho or Shiv with bull

Skand and Visakh

Coin of Kanishk I, with a depiction of the Buddha and legend "Boddo" in Greek script; Ahin Posh

Herakles

Buddh

Coin of Vim Kadphises. Deity Oesho on the reverse, thought to be Shiv, or the Zoroastrian Vayu

Kushan Carnelian seal representing the adsho Atar, with triratana symbol left, and Kanishk the Great's dynastic mark right Kushans and Buddhism :

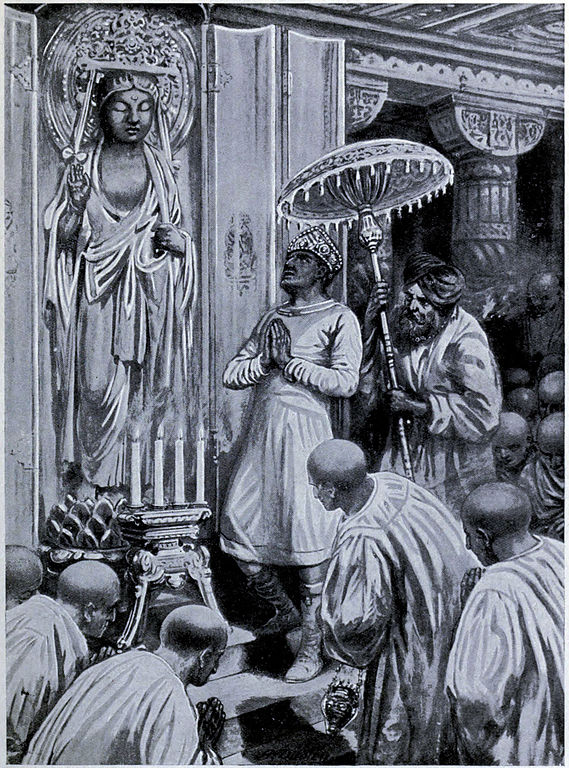

Kanishk the Great inaugurates Mahayan Buddhism. Illustration from 1910

Early Mahayan Buddhist triad. From left to right, a Kushan devotee, Maitreya, the Buddha, Avalokitesvar, and a Buddhist monk. 2nd–3rd century, Gandhar The Kushans inherited the Greco-Buddhist traditions of the Indo-Greek Kingdom they replaced, and their patronage of Buddhist institutions allowed them to grow as a commercial power. Between the mid-1st century and the mid-3rd century, Buddhism, patronized by the Kushans, extended to China and other Asian countries through the Silk Road.

Kanishk is renowned in Buddhist tradition for having convened a great Buddhist council in Kashmir. Along with his predecessors in the region, the Indo-Greek king Menander I (Milind) and the Indian emperors Ashok and Harsh Vardhan, Kanishk is considered by Buddhism as one of its greatest benefactors.

During the 1st century AD, Buddhist books were being produced and carried by monks, and their trader patrons. Also, monasteries were being established along these land routes that went from China and other parts of Asia. With the development of Buddhist books, it caused a new written language called Gandhar. Gandhar consists of eastern Afghanistan and northern Pakistan. Scholars are said to have found many Buddhist scrolls that contained the Gandhari language.

The reign of Huvishk corresponds to the first known epigraphic evidence of the Buddha Amitabh, on the bottom part of a 2nd-century statue which has been found in Govind-Nagar, and now at the Mathura Museum. The statue is dated to "the 28th year of the reign of Huvishk", and dedicated to "Amitabh Buddh" by a family of merchants. There is also some evidence that Huvishk himself was a follower of Mahayan Buddhism. A Sanskrit manuscript fragment in the Schøyen Collection describes Huvishk as one who has "set forth in the Mahayan."

The 12th century historical chronicle Rajatarangini mentions in detail the rule of the Kushan kings and their benevolence towards Buddhism :

Then there ruled in this very land the founders of cities called after their own appellations the three kings named Husk, Jusk and Kanisk These kings albeit belonging to the Turkish race found refuge in acts of piety; they constructed in Suskaletra and other places monasteries, Caityas and similar edificies. During the glorious period of their regime the kingdom of Kashmir was for the most part an appanage of the Buddhists who had acquired lustre by renunciation. At this time since the Nirvan of the blessed Sakya Simha in this terrestrial world one hundred fifty years, it is said, had elapsed. And a Bodhisattva was in this country the sole supreme ruler of the land; he was the illustrious Nagarjun who dwelt in Sadarhadvan.

—

Rajatarangini (I168-I173)

The art and culture of Gandhar, at the crossroads of the Kushan hegemony, developed the traditions of Greco-Buddhist art and are the best known expressions of Kushan influences to Westerners. Several direct depictions of Kushans are known from Gandhar, where they are represented with a tunic, belt and trousers and play the role of devotees to the Buddh, as well as the Bodhisattva and future Buddh Maitreya.

According to Benjamin Rowland, the first expression of Kushan art appears at Khalchayan at the end of the 2nd century BCE. It is derived from Hellenistic art, and possibly from the art of the cities of Ai-Khanoum and Nysa, and clearly has similarities with the later Art of Gandhar, and may even have been at the origin of its development.Rowland particularly draws attention to the similarity of the ethnic types represented at Khalchayan and in the art of Gandhar, and also in the style of portraiture itself. For example, Rowland find a great proximity between the famous head of a Yuezhi prince from Khalchayan, and the head of Gandharn Bodhisattvas, giving the example of the Gandharn head of a Bodhisattva in the Philadelphia Museum. The similarity of the Gandhar Bodhisattva with the portrait of the Kushan ruler Heraios is also striking. According to Rowland the Bactrian art of Khalchayan thus survived for several centuries through its influence in the art of Gandhar, thanks to the patronage of the Kushans.

During the Kushan Empire, many images of Gandhar share a strong resemblance to the features of Greek, Syrian, Persian and Indian figures. These Western-looking stylistic signatures often include heavy drapery and curly hair, representing a composite (the Greeks, for example, often possessed curly hair).

As the Kushans took control of the area of Mathura as well, the Art of Mathura developed considerably, and free-standing statues of the Buddh came to be mass-produced around this time, possibly encouraged by doctrinal changes in Buddhism allowing to depart from the aniconism that had prevailed in the Buddhist sculptures at Mathura, Bharhut or Sanchi from the end of the 2nd century BCE. The artistic cultural influence of kushans declined slowly due to Hellenistic greek and Indian influences.

Dated Buddhist statuary under the Kushans

Kanishk

I

Kosambi

Bodhisattva, inscribed "Year 2 of Kanishk" (129 CE)

Bala

Bodhisattva, Sarnath, inscribed "Year 3 of Kanishk" (130

CE)

Kanishk

I

"Kimbell

seated Buddh", with inscription "Year 4 of Kanishk"

(131 CE). Another similar statue has "Year 32 of Kanishk"

Kanishk

I

Buddh

from Loriyan Tangai with inscription mentioning the "year 318"

of the Yavan era (143 CE)

Vasudev

I

Hashtnagar

Buddh and its piedestal, inscribed with "year 384" of

the Yavan era (c.209 CE)

Vasudev

I

Mamane

Dheri Buddh, inscribed with "Year 89", probably of the

Kanishk era (216 CE)

Kanishk

II Kushan

coinage :

The coinage of the Kushans was copied as far as the Kushano-Sasanians in the west, and the kingdom of Samatat in Bengal to the east. The coinage of the Gupta Empire was also initially derived from the coinage of the Kushan Empire, adopting its weight standard, techniques and designs, following the conquests of Samudragupt in the northwest. The imagery on Gupta coins then became more Indian in both style and subject matter compared to earlier dynasties, where Greco-Roman and Persian styles were mostly followed.

Contacts with Rome :

Roman coinage among the Kushans

Coin of the Roman Emperor Trajan, found together with coins of Kanishk the Great at the Ahin Posh Monastery

Kushan ring with inscription in the Brahmi script, with portraits of Roman rulers Septimus Severus and Julia Domna Several Roman sources describe the visit of ambassadors from the Kings of Bactria and India during the 2nd century, probably referring to the Kushans.

Historia Augusta, speaking of Emperor Hadrian (117 – 138) tells :

Greco-Roman gladiator on a glass vessel, Begram, 2nd century Reges Bactrianorum legatos ad eum, amicitiae petendae causa, supplices miserunt "The kings of the Bactrians sent supplicant ambassadors to him, to seek his friendship."

Also in 138, according to Aurelius Victor (Epitome‚ XV, 4), and Appian (Praef., 7), Antoninus Pius, successor to Hadrian, received some Indian, Bactrian, and Hyrcanian ambassadors.

"Precious things from Da Qin [the Roman Empire] can be found there [in Tianzhu or Northwestern India], as well as fine cotton cloths, fine wool carpets, perfumes of all sorts, sugar candy, pepper, ginger, and black salt."

—

Hou Hanshu

Contacts with China :

The Kushan Buddhist monk Lokaksema, first known translator of Buddhist Mahayana scriptures into Chinese, c. 170 During the 1st and 2nd century, the Kushan Empire expanded militarily to the north, putting them at the center of the profitable Central Asian commerce. They are related to have collaborated militarily with the Chinese against nomadic incursion, particularly when they collaborated with the Han dynasty general Ban Chao against the Sogdians in 84, when the latter were trying to support a revolt by the king of Kashgar. Around 85, they also assisted the Chinese general in an attack on Turpan, east of the Tarim Basin.

Kushan coinage in China

A bronze coin of Kanishk the Great found in Khotan, Tarim Basin

Eastern Han inscriptions on lead ingot, using barbarous Greek alphabet in the style of the Kushans, excavated in Shaanxi, 1st–2nd century CE In recognition for their support to the Chinese, the Kushans requested a Han princess, but were denied, even after they had sent presents to the Chinese court. In retaliation, they marched on Ban Chao in 86 with a force of 70,000, but were defeated by a smaller Chinese force. The Yuezhi retreated and paid tribute to the Chinese Empire during the reign of emperor He of Han (89–106).

The Kushans are again recorded to have sent presents to the Chinese court in 158–159 during the reign of Emperor Huan of Han.

Following these interactions, cultural exchanges further increased, and Kushan Buddhist missionaries, such as Lokaksema, became active in the Chinese capital cities of Loyang and sometimes Nanjing, where they particularly distinguished themselves by their translation work. They were the first recorded promoters of Hinayana and Mahayana scriptures in China, greatly contributing to the Silk Road transmission of Buddhism.

Decline

:

Sasanian control of the Western Kushans

Hormizd I Kushanshah (277–286 CE), king of the Indo-Sasanians, maintained Sasanian rule in former Kushan territories of the northwest. Naqsh-e Rustam Bahram II panel

The Kushano-Sasanians imitated the Kushans in some of their Bactrian coinage. Coin of Sasanian ruler Peroz I Kushanshah, with Bactrian legend around "Peroz the Great Kushan King" After the death of Vasudev I in 225, the Kushan empire split into western and eastern halves. The Western Kushans (in Afghanistan) were soon subjugated by the Persian Sasanian Empire and lost Sogdiana, Bactria, and Gandhar to them. The Sassanian king Shapur I (240–270 CE) claims in his Naqsh-e Rostam inscription possession of the territory of the Kushans (Kušan šahr) as far as "Purushpur" (Peshawar), suggesting he controlled Bactria and areas as far as the Hindu-Kush or even south of it:

I, the Mazda-worshipping lord, Shapur, king of kings of Iran and An-Iran… (I) am the Master of the Domain of Iran (Eranšahr) and possess the territory of Persis, Parthian… Hindestan, the Domain of the Kushan up to the limits of Paškabur and up to Kash, Sughd, and Chachestan.

—

Shapur I's inscription at the Ka'ba-ye Zartosht, Naqsh-e Rostam

The Sasanians deposed the Western dynasty and replaced them with Persian vassals known as the Kushanshas (in Bactrian on their coinage: Koshano Shao) also called Indo-Sasanians or Kushano-Sasanians. The Kushano-Sasanians ultimately became very powerful under Hormizd I Kushanshah (277–286 CE) and rebelled against the Sasanian Empire, while continuing many aspects of the Kushan culture, visible in particular in their titulature and their coinage.

"Little Kushans" and Gupta suzerainty :

Gupta control over the Eastern Kushans

The expression Devaputra Shahi Shahanu Shahi in Middle Brahmi in the Allahabad pillar (Line 23), claimed by Samudragupta to be under his dominion.

Coin

minted in the Punjab area with the name "Samudra" (Sa-mu-dra),

thought to be the Gupta ruler Samudragupt. These coins imitate those

of the last Kushan ruler Kipunad, and precede the coinage of the

first Kidarite Huns in northwestern India. Circa CE 350-375.

Numimastics indicate that the coinage of the Eastern Kushans was much weakened: silver coinage was abandoned altogether, and gold coinage was debased. This suggests that the Eastern Kushans had lost their central trading role on the trade routes that supplied luxury goods and gold. Still, the Buddhist art of Gandhar continued to flourish, and cities such as Sirsukh near Taxila were established.

Sasanian,

Kidarite and Alchon invasions :

In 360 a Kidarite Hun named Kidar overthrew the Kushano-Sasanians and remnants of the old Kushan dynasty, and established the Kidarite Kingdom. The Kushan style of Kidarite coins indicates they claimed Kushan heritage. The Kidarite seem to have been rather prosperous, although on a smaller scale than their Kushan predecessors. East of the Punjab, the former eastern territories of the Kushans were controlled by the mighty Gupta Empire.

The remnants of Kushan culture under the Kidarites in the northwest were ultimately wiped out in the end of the 5th century by the invasions of the Alchon Huns (sometimes considered as a branch of the Hephthalites), and later the Nezak Huns.

Rulers

:

•

Heraios (c. 1

– 30), first king to call himself "Kushan" on his

coinage

To view Kushan Empire Emperors, territories and chronology Click here.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg)

.jpg)