| MAGI Magi (singular magus; from Latin magus) were priests in Zoroastrianism and the earlier religions of the western Iranians. The earliest known use of the word Magi is in the trilingual inscription written by Darius the Great, known as the Behistun Inscription. Old Persian texts, predating the Hellenistic period, refer to a magus as a Zurvanic, and presumably Zoroastrian, priest.

Pervasive throughout the Eastern Mediterranean and Western Asia until late antiquity and beyond, mágos was influenced by (and eventually displaced) Greek goes, the older word for a practitioner of magic, to include astronomy/astrology, alchemy and other forms of esoteric knowledge.

This association was in turn the product of the Hellenistic fascination for (Pseudo-) Zoroaster, who was perceived by the Greeks to be the Chaldean founder of the Magi and inventor of both astrology and magic, a meaning that still survives in the modern-day words "magic" and "magician".

In the Gospel of Matthew, magoi from the east do homage to the newborn Jesus, and the transliterated plural "magi" entered English from Latin in this context around 1200 (this particular use is also commonly rendered in English as "kings" and more often in recent times as "wise men"). The singular "magus" appears considerably later, when it was borrowed from Old French in the late 14th century with the meaning magician.

Iranian

sources :

The other instance appears in the texts of the Avesta, the sacred literature of Zoroastrianism. In this instance, which is in the Younger Avestan portion, the term appears in the hapax moghu.tbiš, meaning "hostile to the moghu", where moghu does not (as was previously thought) mean "magus", but rather "a member of the tribe" or referred to a particular social class in the proto-Iranian language and then continued to do so in Avestan.

An unrelated term, but previously assumed to be related, appears in the older Gathic Avestan language texts. This word, adjectival magavan meaning "possessing maga-", was once the premise that Avestan maga- and Median (i.e. Old Persian) magu- were co-eval (and also that both these were cognates of Vedic Sanskrit magh-). While "in the Gathas the word seems to mean both the teaching of Zoroaster and the community that accepted that teaching", and it seems that Avestan maga- is related to Sanskrit magha-, "there is no reason to suppose that the western Iranian form magu (Magus) has exactly the same meaning" as well. But it "may be, however", that Avestan moghu (which is not the same as Avestan maga-) "and Medean magu were the same word in origin, a common Iranian term for 'member of the tribe' having developed among the Medes the special sense of 'member of the (priestly) tribe', hence a priest."cf

Greco-Roman

sources :

Better preserved are the descriptions of the mid-5th century BCE Herodotus, who in his portrayal of the Iranian expatriates living in Asia minor uses the term "magi" in two different senses. In the first sense (Histories 1.101), Herodotus speaks of the magi as one of the tribes/peoples (ethnous) of the Medes. In another sense (1.132), Herodotus uses the term "magi" to generically refer to a "sacerdotal caste", but "whose ethnic origin is never again so much as mentioned." According to Robert Charles Zaehner, in other accounts, "we hear of Magi not only in Persia, Parthia, Bactria, Chorasmia, Aria, Media, and among the Sakas, but also in non-Iranian lands like Samaria, Ethiopia, and Egypt. Their influence was also widespread throughout Asia Minor. It is, therefore, quite likely that the sacerdotal caste of the Magi was distinct from the Median tribe of the same name."

As early as the 5th century BCE, Greek magos had spawned mageia and magike to describe the activity of a magus, that is, it was his or her art and practice. But almost from the outset the noun for the action and the noun for the actor parted company. Thereafter, mageia was used not for what actual magi did, but for something related to the word 'magic' in the modern sense, i.e. using supernatural means to achieve an effect in the natural world, or the appearance of achieving these effects through trickery or sleight of hand. The early Greek texts typically have the pejorative meaning, which in turn influenced the meaning of magos to denote a conjurer and a charlatan. Already in the mid-5th century BC, Herodotus identifies the magi as interpreters of omens and dreams (Histories 7.19, 7.37, 1.107, 1.108, 1.120, 1.128).

Other Greek sources from before the Hellenistic period include the gentleman-soldier Xenophon, who had first-hand experience at the Persian Achaemenid court. In his early 4th century BCE Cyropaedia, Xenophon depicts the magians as authorities for all religious matters (8.3.11), and imagines the magians to be responsible for the education of the emperor-to-be.

Roman

period :

"Zoroaster" – or rather what the Greeks supposed him to be – was for the Hellenists the figurehead of the 'magi', and the founder of that order (or what the Greeks considered to be an order). He was further projected as the author of a vast compendium of "Zoroastrian" pseudepigrapha, composed in the main to discredit the texts of rivals. "The Greeks considered the best wisdom to be exotic wisdom" and "what better and more convenient authority than the distant – temporally and geographically – Zoroaster?" The subject of these texts, the authenticity of which was rarely challenged, ranged from treatises on nature to ones on necromancy. But the bulk of these texts dealt with astronomical speculations and magical lore.

One factor for the association with astrology was Zoroaster's name, or rather, what the Greeks made of it. His name was identified at first with star-worshiping (astrothytes "star sacrificer") and, with the Zo-, even as the living star. Later, an even more elaborate mytho-etymology evolved: Zoroaster died by the living (zo-) flux (-ro-) of fire from the star (-astr-) which he himself had invoked, and even that the stars killed him in revenge for having been restrained by him. The second, and "more serious" factor for the association with astrology was the notion that Zoroaster was a Chaldean.

The alternate Greek name for Zoroaster was Zaratas / Zaradas / Zaratos (cf. Agathias 2.23–5, Clement Stromata I.15), which – according to Bidez and Cumont – derived from a Semitic form of his name. The Suda's chapter on astronomia notes that the Babylonians learned their astrology from Zoroaster. Lucian of Samosata (Mennipus 6) decides to journey to Babylon "to ask one of the magi, Zoroaster's disciples and successors", for their opinion.

In Christian tradition :

Byzantine depiction of the Three Magi in a 6th-century mosaic at Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo

Conventional post-12th century depiction of the Biblical magi (Adoração dos Magos by Vicente Gil). Balthasar, the youngest magus, bears frankincense and represents Africa. To the left stands Caspar, middle-aged, bearing gold and representing Asia. On his knees is Melchior, oldest, bearing myrrh and representing Europe.

The word mágos (Greek) and its variants appear in both the Old and New Testaments. Ordinarily this word is translated "magician" or "sorcerer" in the sense of illusionist or fortune-teller, and this is how it is translated in all of its occurrences (e.g. Acts 13:6) except for the Gospel of Matthew, where, depending on translation, it is rendered "wise man" (KJV, RSV) or left untranslated as Magi, typically with an explanatory note (NIV). However, early church fathers, such as St. Justin, Origen, St. Augustine and St. Jerome, did not make an exception for the Gospel, and translated the word in its ordinary sense, i.e. as "magician".

The Gospel of Matthew states that magi visited the infant Jesus to do him homage shortly after his birth (2:1–2:12). The gospel describes how magi from the east were notified of the birth of a king in Judaea by the appearance of his star. Upon their arrival in Jerusalem, they visited King Herod to determine the location of the king of the Jews's birthplace. Herod, disturbed, told them that he had not heard of the child, but informed them of a prophecy that the Messiah would be born in Bethlehem. He then asked the magi to inform him when they find the infant so that Herod may also worship him. Guided by the Star of Bethlehem, the wise men found the baby Jesus in a house; Matthew does not say if the house was in Bethlehem. They worshiped him, and presented him with "gifts of gold and of frankincense and of myrrh." (2.11) In a dream they are warned not to return to Herod, and therefore return to their homes by taking another route. Since its composition in the late 1st century, numerous apocryphal stories have embellished the gospel's account. Matthew 2:16 implies that Herod learned from the wise men that up to two years had passed since the birth, which is why all male children two years or younger were slaughtered.

In addition to the more famous story of Simon Magus found in chapter 8, the Book of Acts (13:6–11) also describes another magus who acted as an advisor of Sergius Paulus, the Roman proconsul at Paphos on the island of Cyprus. He was a Jew named Bar-Jesus (son of Jesus), or alternatively Elymas. (Another Cypriot magus named Atomos is referenced by Josephus, working at the court of Felix at Caesarea.)

One of the non-canonical Christian sources, the Syriac Infancy Gospel, provides, in its third chapter, a story of the wise men of the East which is very similar to much of the story in Matthew. This account cites Zoradascht (Zoroaster) as the source of the prophecy that motivated the wise men to seek the infant Jesus.

In

Islamic tradition :

In the 1980s, Saddam Hussein's Ba'ath Party used the term majus during the Iran–Iraq War as a generalization of all modern-day Iranians. "By referring to the Iranians in these documents as majus, the security apparatus [implied] that the Iranians [were] not sincere Muslims, but rather covertly practice their pre-Islamic beliefs. Thus, in their eyes, Iraq's war took on the dimensions of not only a struggle for Arab nationalism, but also a campaign in the name of Islam."

Possible loan into Chinese :

Victor H. Mair (1990) suggested that Chinese wu ("shaman; witch, wizard; magician") may originate as a loanword from Old Persian *maguš "magician; magi". Mair reconstructs an Old Chinese *myag. The reconstruction of Old Chinese forms is somewhat speculative. The velar final -g in Mair's *myag is evident in several Old Chinese reconstructions (Dong Tonghe's *mywag, Zhou Fagao's *mjway, and Li Fanggui's *mjag), but not all (Bernhard Karlgren's *mywo and Axel Schuessler's *ma).

Mair adduces the discovery of two figurines with unmistakably Caucasoid or Europoid features dated to the 8th century BCE, found in a 1980 excavation of a Zhou Dynasty palace in Fufeng County, Shaanxi Province. One of the figurines is marked on the top of its head with an incised graph.

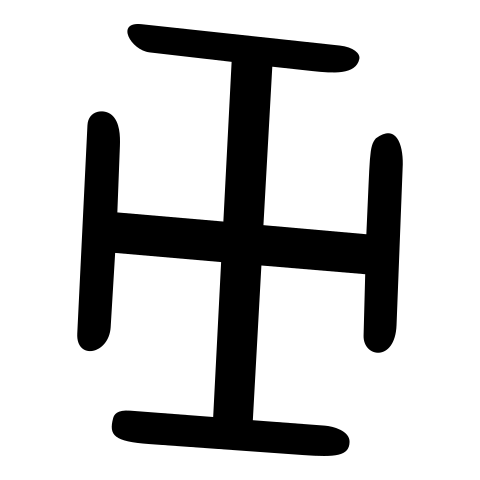

Mair's suggestion is based on a proposal by Jao Tsung-I (1990), which connects the "cross potent" Bronzeware script glyph for wu ? with the same shape found in Neolithic West Asia, specifically a cross potent carved in the shoulder of a goddess figure of the Halaf period.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

.jpg)