| NOMAD

A painting by Vincent van Gogh depicting a caravan of nomadic Romani A nomad (Middle French: nomade "people without fixed habitation") [dubious – discuss] is a member of a community without fixed habitation which regularly moves to and from the same areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), and tinkers or trader nomads. In the twentieth century, population of nomadic pastoral tribes slowly decreased, reaching to an estimated 30–40 million nomads in the world as of 1995.

Nomadic hunting and gathering—following seasonally available wild plants and game—is by far the oldest human subsistence method. Pastoralists raise herds, driving or accompanying in patterns that normally avoid depleting pastures beyond their ability to recover.

Nomadism is also a lifestyle adapted to infertile regions such as steppe, tundra, or ice and sand, where mobility is the most efficient strategy for exploiting scarce resources. For example, many groups living in the tundra are reindeer herders and are semi-nomadic, following forage for their animals.

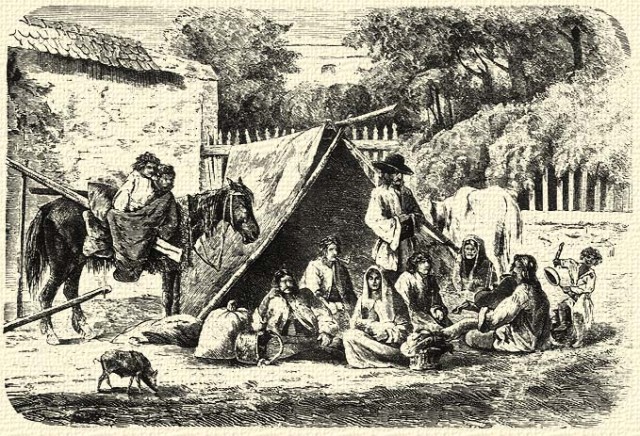

Sometimes also described as "nomadic" are the various itinerant populations who move among densely populated areas to offer specialized services (crafts or trades) to their residents—external consultants, for example. These groups are known [by whom?] as "peripatetic nomads".

Common characteristics :

Romani mother and child

Nomads on the Changtang, Ladakh

Rider in Mongolia, 2012s. While nomadic life is less common in modern times, the horse remains a national symbol in Mongolia

Beja nomads from Northeast Africa

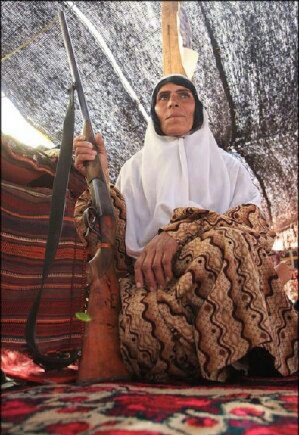

A woman from the Afshar clan on the edge of the Khabar National Park in southeastern Iraq A nomad is a person with no settled home, moving from place to place as a way of obtaining food, finding pasture for livestock, or otherwise making a living. The word "nomad" comes ultimately from the classical Greek word (nomás, "roaming, wandering, especially to find pasture"), from Ancient Greek (nomós, "pasture"). Most nomadic groups follow a fixed annual or seasonal pattern of movements and settlements. Nomadic peoples traditionally travel by animal or canoe or on foot. Today, some nomads travel by motor vehicle. Most [quantify] nomads live in homes or other homeless shelters.

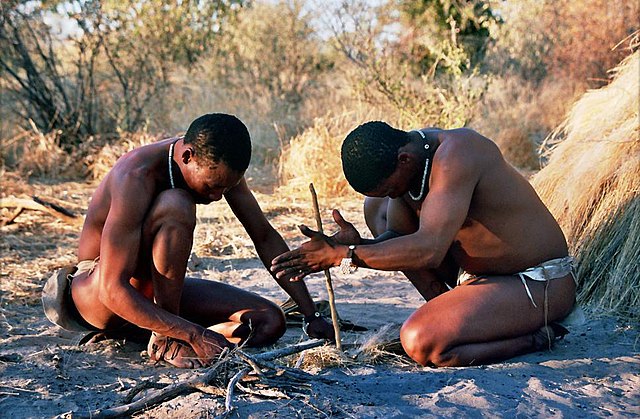

Nomads keep moving for different reasons. Nomadic foragers move in search of game, edible plants, and water. Aboriginal Australians, Negritos of Southeast Asia, and San of Africa, for example, traditionally move from camp to camp to hunt and gather wild plants. Some tribes of the Americas followed this way of life. Pastoral nomads, on the other hand, make their living raising livestock such as camels, cattle, goats, horses, sheep, or yaks; these nomads usually travel in search of pastures for their flocks. The Fulani and their cattle travel through the grasslands of Niger in western Africa. Some nomadic peoples, especially herders, may also move to raid settled communities or to avoid enemies. Nomadic craftworkers and merchants travel to find and serve customers. They include the Lohar blacksmiths of India, the Romani traders, Scottish travelers, Irish travelers.

Most nomads travel in groups of families, bands, or tribes. These groups are based on kinship and marriage ties or on formal agreements of cooperation. A council of adult males makes most of the decisions, though some tribes have chiefs.

In the case of Mongolian nomads, a family moves twice a year. These two movements generally occur during the summer and winter. The winter destination is usually located near the mountains in a valley and most families already have fixed winter locations. Their winter locations have shelter for animals and are not used by other families while they are out. In the summer they move to a more open area that the animals can graze. Most nomads usually move in the same region and don't travel very far to a totally different region. Since they usually circle around a large area, communities form and families generally know where the other ones are. Often, families do not have the resources to move from one province to another unless they are moving out of the area permanently. A family can move on its own or with others; if it moves alone, they are usually no more than a couple of kilometers from each other. Nowadays there are no tribes and decisions are made among family members, although elders consult with each other on usual matters. The geographical closeness of families is usually for mutual support. Pastoral nomad societies usually do not have a large population. One such society, the Mongols, gave rise to the largest land empire in history. The Mongols originally consisted of loosely organized nomadic tribes in Mongolia, Manchuria, and Siberia. In the late 12th century, Genghis Khan united them and other nomadic tribes to found the Mongol Empire, which eventually stretched the length of Asia.

The nomadic way of life has become increasingly rare. Many countries have converted pastures into cropland and forced nomadic peoples into permanent settlements.[citation needed]

Although (or because) "[t]he sedentary man envies the nomadic existence, the heck for green pastures" sedentarist prejudice against nomads, "shiftless" "gypsies", "rootless cosmopolitans", "primitive" hunter-gatherers, refugees and urban homeless street-people persists.

Hunter-gatherers :

Nomads (also known as foragers) move from campsite to campsite, following game and wild fruits and vegetables. Hunting and gathering describes early people's subsistence living style. Following the development of agriculture, most hunter-gatherers were eventually either displaced or converted to farming or pastoralist groups. Only a few contemporary societies are classified as hunter-gatherers; and some of these supplement, sometimes extensively, their foraging activity with farming or keeping animals.

Pastoralism :

Cuman nomads, Radziwill Chronicle, 13th century

An 1848 Lithograph showing nomads in Afghanistan

A yurt in front of the Gurvan Saikhan Mountains. Approximately 30% of the Mongolia's 3 million people are nomadic or semi-nomadic

A Sámi family in Norway around 1900. Reindeer have been herded for centuries by several Arctic and Subarctic people including the Sámi and the Nenets Pastoral nomads are nomads moving between pastures. Nomadic pastoralism is thought to have developed in three stages that accompanied population growth and an increase in the complexity of social organization. Karim Sadr has proposed the following stages:

•

Pastoralism :

This is a mixed economy with a symbiosis within the family.

Origin

:

The first nomadic pastoral society developed in the period from 8,500–6,500 BCE in the area of the southern Levant. There, during a period of increasing aridity, Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) cultures in the Sinai were replaced by a nomadic, pastoral pottery-using culture, which seems to have been a cultural fusion between a newly arrived Mesolithic people from Egypt (the Harifian culture), adopting their nomadic hunting lifestyle to the raising of stock.

This lifestyle quickly developed into what Jaris Yurins has called the circum-Arabian nomadic pastoral techno-complex and is possibly associated with the appearance of Semitic languages in the region of the Ancient Near East. The rapid spread of such nomadic pastoralism was typical of such later developments as of the Yamnaya culture of the horse and cattle nomads of the Eurasian steppe, or of the Mongol spread of the later Middle Ages.

Trekboer in southern Africa adopted nomadism from the 17th century.

Increase

in post-Soviet Central Asia :

Since the 1990s, as the cash economy shrank, unemployed relatives were reabsorbed into family farms, and the importance of this form of nomadism has increased. [citation needed] The symbols of nomadism, specifically the crown of the grey felt tent known as the yurt, appears on the national flag, emphasizing the central importance of nomadism in the genesis of the modern nation of Kyrgyzstan.

Sedentarization

:

In Kazakhstan where the major agricultural activity was nomadic herding, forced collectivization under Joseph Stalin's rule met with massive resistance and major losses and confiscation of livestock. Livestock in Kazakhstan fell from 7 million cattle to 1.6 million and from 22 million sheep to 1.7 million. The resulting famine of 1931–1934 caused some 1.5 million deaths: this represents more than 40% of the total Kazakh population at that time.

In the 1950s as well as the 1960s, large numbers of Bedouin throughout the Middle East started to leave the traditional, nomadic life to settle in the cities of the Middle East, especially as home ranges have shrunk and population levels have grown. Government policies in Egypt and Israel, oil production in Libya and the Persian Gulf, as well as a desire for improved standards of living, effectively led most Bedouin to become settled citizens of various nations, rather than stateless nomadic herders. A century ago nomadic Bedouin still made up some 10% of the total Arab population. Today they account for some 1% of the total.

At independence in 1960, Mauritania was essentially a nomadic society. The great Sahel droughts of the early 1970s caused massive problems in a country where 85% of its inhabitants were nomadic herders. Today only 15% remain nomads.

As many as 2 million nomadic Kuchis wandered over Afghanistan in the years before the Soviet invasion, and most experts agreed that by 2000 the number had fallen dramatically, perhaps by half. The severe drought had destroyed 80% of the livestock in some areas.

Niger experienced a serious food crisis in 2005 following erratic rainfall and desert locust invasions. Nomads such as the Tuareg and Fulani, who make up about 20% of Niger's 12.9 million population, had been so badly hit by the Niger food crisis that their already fragile way of life is at risk. Nomads in Mali were also affected.

Lifestyle :

Tents of Pashtun nomads in Badghis Province, Afghanistan. They migrate from region to region depending on the season Pala nomads living in Western Tibet have a diet that is unusual in that they consume very few vegetables and no fruit. The main staple of their diet is tsampa and they drink Tibetan style butter tea. Pala will eat heartier foods in the winter months to help keep warm. Some of the customary restrictions they explain as cultural saying only that drokha do not eat certain foods, even some that may be naturally abundant. Though they live near sources of fish and fowl these do not play a significant role in their diet, and they do not eat carnivorous animals, rabbits or the wild asses that are abundant in the environs, classifying the latter as horse due to their cloven hooves. Some families do not eat until after the morning milking, while others may have a light meal with butter tea and tsampa. In the afternoon, after the morning milking, the families gather and share a communal meal of tea, tsampa and sometimes yogurt. During winter months the meal is more substantial and includes meat. Herders will eat before leaving the camp and most do not eat again until they return to camp for the evening meal. The typical evening meal may include thin stew with tsampa, animal fat and dried radish. Winter stew would include a lot of meat with either tsampa or boiled flour dumplings.

Nomadic diets in Kazakhstan have not changed much over centuries. The Kazakh nomad cuisine is simple and includes meat, salads, marinated vegetables and fried and baked breads. Tea is served in bowls, possibly with sugar or milk. Milk and other dairy products, like cheese and yogurt, are especially important. Kumiss is a drink of fermented milk. Wrestling is a popular sport, but the nomadic people do not have much time for leisure. Horse riding is a valued skill in their culture.

Contemporary peripatetic minorities in Europe and Asia :

Peripatetic minorities are mobile populations moving among settled populations offering a craft or trade.

Each existing community is primarily endogamous, and subsists traditionally on a variety of commercial or service activities. Formerly, all or a majority of their members were itinerant, and this largely holds true today. Migration generally takes place within the political boundaries of a single state these days.

Each of the peripatetic communities is multilingual, it speaks one or more of the languages spoken by the local sedentary populations, and, additionally, within each group, a separate dialect or language is spoken. They are speaking languages of Indic origin and many are structured somewhat like an argot or secret language, with vocabularies drawn from various languages. There are indications that in northern Iran at least one community speaks Romani language, and some groups in Turkey also speak Romani.

Dom

people :

In Iran the Asheq of Azerbaijan, the Challi of Baluchistan, the Luti of Kurdistan, Kermanshah, Ilam, and Lorestan, the Mehtar in the Mamasani district, the Sazandeh of Band-i Amir and Marv-dasht, and the Toshmal among the Bakhtyari pastoral groups worked as professional musicians. The men among the Kowli worked as tinkers, smiths, musicians, and monkey and bear handlers; they also made baskets, sieves, and brooms and dealt in donkeys. Their women made a living from peddling, begging, and fortune-telling.

The Ghorbat among the Basseri were smiths and tinkers, traded in pack animals, and made sieves, reed mats, and small wooden implements. In the Fars region, the Qarbalband, the Kuli, and Luli were reported to work as smiths and to make baskets and sieves; they also dealt in pack animals, and their women peddled various goods among pastoral nomads. In the same region, the Changi and Luti were musicians and balladeers, and their children learned these professions from the age of 7 or 8 years.[citation needed]

The nomadic groups in Turkey make and sell cradles, deal in animals, and play music. The men of the sedentary groups work in towns as scavengers and hangmen; elsewhere they are fishermen, smiths, basket makers, and singers; their women dance at feasts and tell fortunes. Abdal men played music and made sieves, brooms, and wooden spoons for a living. The Tahtaci traditionally worked as lumberers; with increased sedentarization, however, they have taken to agriculture and horticulture.[citation needed]

Little is known for certain about the past of these communities; the history of each is almost entirely contained in their oral traditions. Although some groups—such as the Vangawala—are of Indian origin, some—like the Noristani—are most probably of local origin; still others probably migrated from adjoining areas. The Ghorbat and the Shadibaz claim to have originally come from Iran and Multan, respectively, and Tahtaci traditional accounts mention either Baghdad or Khorasan as their original home. The Baluch say they [clarification needed] were attached as a service community to the Jamshedi, after they fled Baluchistan because of feuds.

Yörüks :

Image gallery :

Mongol nomads in the Altai Mountains

Snake charmer from Telungu community of Sri Lanka

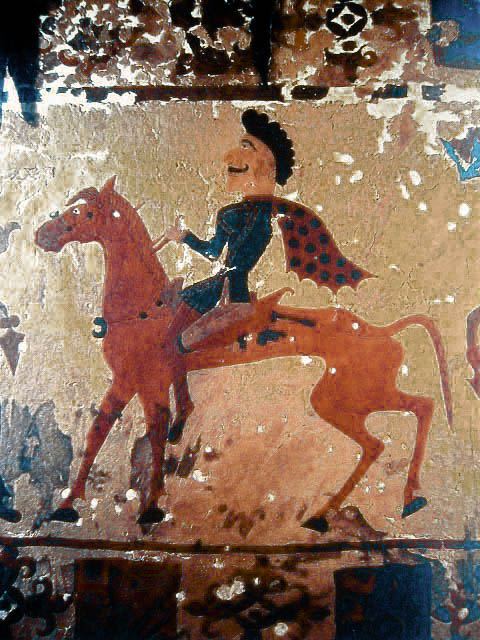

A Scythian horseman from the general area of the Ili river, Pazyryk, c. 300 BCE

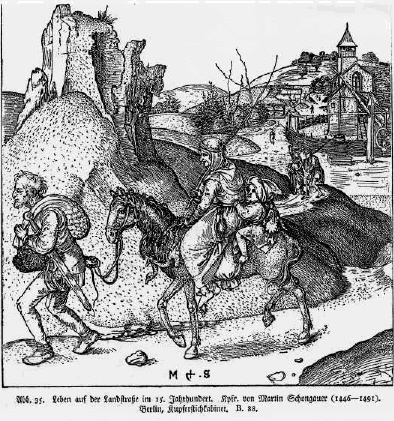

Yeniche people in the 15th century

A young Bedouin lighting a camp fire in Wadi Rum, Jordan

Kyrgyz nomads in the steppes of the Russian Empire, Uzbekistan, by pioneer color photographer Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky, c. 1910

Tuareg in Mali, 1974

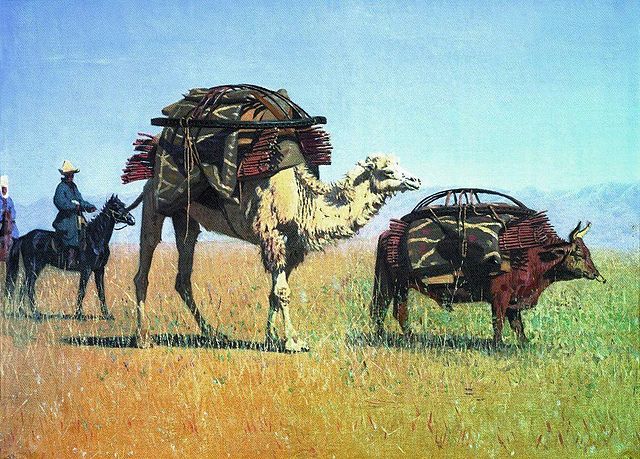

Kyrgyz nomads, 1869 – 1870

Nomads in the Desert (Giulio Rosati)

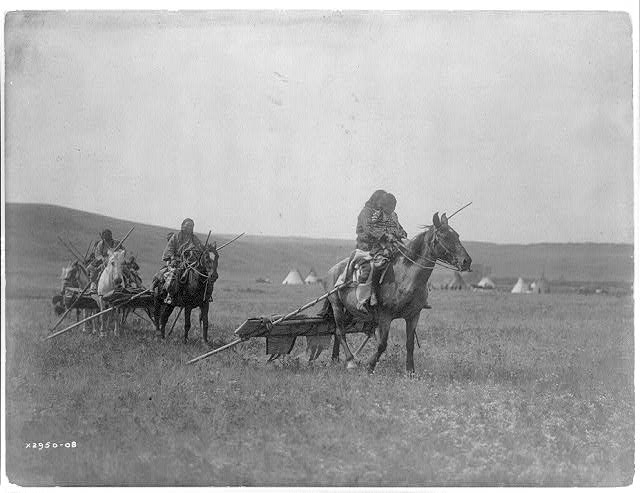

Gros Ventre (Atsina) American Indians moving camps with travois for transporting skin lodges and belongings

House barge of the Sama-Bajau peoples, Indonesia. 1914 – 1921

Photograph of Bedouins (wandering Arabs) of Tunisia, 1899

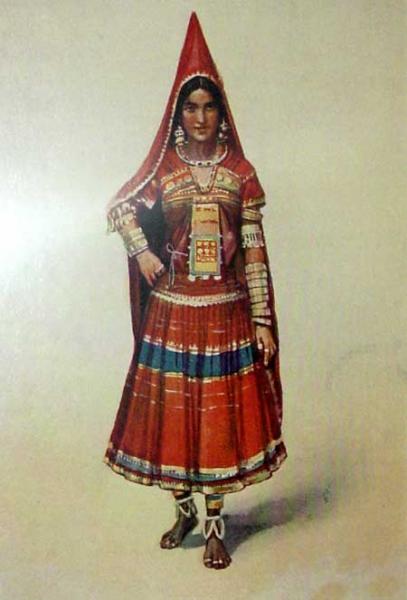

Indian nomads painting by well-known artiste Raja Ravi Varma Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

_(14592471478).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)