| OSSETIAN LANGUAGE

Ethnolinguistic groups in the Caucasus region. Ossetian-speaking regions are shaded gold

Language codes :

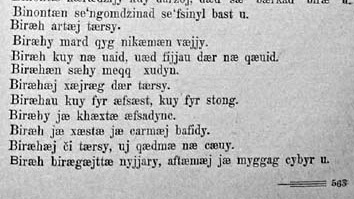

Ossetian text from a book published in 1935. Part of an alphabetic list of proverbs. Latin script.

Ossetian, more commonly called Ossetic and rarely Ossete (Romanized: iron ævzag), is an Eastern Iranian language spoken in Ossetia, a region on the northern slopes of the Caucasus Mountains. It is a relative and possibly a descendant of the extinct Scythian, Sarmatian, and Alanic languages.

The Ossete area in Russia is known as North Ossetia–Alania, while the area south of the border is referred to as South Ossetia, recognised by Russia, Nicaragua, Venezuela and Nauru as an independent state but by most of the rest of the international community as part of Georgia. Ossetian speakers number about 614,350, with 451,000 speakers in the Russian Federation recorded in the 2010 census.

History

and classification :

From deep Antiquity (since the 7th–8th centuries BC), the languages of the Iranian group were distributed in a vast territory including present-day Iran (Persia), Central Asia, Eastern Europe and the Caucasus. Ossetian is the sole survivor of the branch of Iranian languages known as Scythian. The Scythian group included numerous tribes, known in ancient sources as the Scythians, Massagetae, Saka, Sarmatians, Alans and Roxolans. The more easterly Khorezmians and the Sogdians were also closely affiliated, in linguistic terms.

Ossetian, together with Kurdish, Tati and Talyshi, is one of the main Iranian languages with a sizable community of speakers in the Caucasus. It is descended from Alanic, the language of the Alans, medieval tribes emerging from the earlier Sarmatians. It is believed to be the only surviving descendant of a Sarmatian language.

The closest genetically related language may be the Yaghnobi language of Tajikistan, the only other living Northeastern Iranian language. Ossetian has a plural formed by the suffix -ta, a feature it shares with Yaghnobi, Sarmatian and the now-extinct Sogdian; this is taken as evidence of a formerly wide-ranging Iranian-language dialect continuum on the Central Asian steppe. The names of ancient Iranian tribes (as transmitted through Ancient Greek) in fact reflect this pluralization, e.g. Saromatae and Masagetae.

Evidence

for Medieval Ossetian :

Marginalia of Greek religious books, with some parts (such as headlines) of the book translated into Old Ossetic, have been recently found.

It is theorized that during the Proto-Ossetic phase, Ossetian underwent a process of phonological change conditioned by a Rhythmusgesetz or "Rhythm-law" whereby nouns were divided into two classes, those heavily or lightly stressed. "Heavy-stem" nouns possessed a "heavy" long vowel or diphthong, and were stressed on the first-occurring syllable of this type; "light-stem" nouns were stressed on their final syllable. This is precisely the situation observed in the earliest (though admittedly scanty) records of Ossetian presented above. This situation also obtains in Modern Ossetian, although the emphasis in Digor is also affected by the "openness" of the vowel. The trend is also found in a glossary of the Jassic dialect dating from 1422.

Dialects

:

Grammar

:

In the course of centuries-long propinquity to and intercourse with Caucasian languages, Ossetian became similar to them in some features, particularly in phonetics and lexicon. However, it retained its grammatical structure and basic lexical stock; its relationship with the Iranian family, despite considerable individual traits, does not arouse any doubt.

Nouns

:

Definiteness

:

Cases

:

Verbs

:

Ossetic uses mostly postpositions (derived from nouns), although two prepositions exist in the language. Noun modifiers precede nouns. The word order is not rigid, but tends towards SOV. The morphosyntactic alignment is nominative–accusative, although there is no accusative case: rather, the direct object is in the nominative (typically if inanimate or indefinite) or in the genitive (typically if animate or definite).

For numerals above 20, two systems are in use – a decimal one used officially, and a vigesimal one used colloquially.

Writing system :

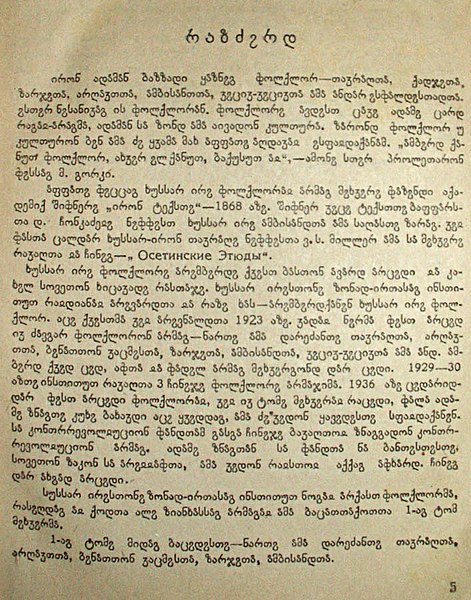

Ossetic text written with Georgian script, from a book on Ossetian folklore published in 1940 in South Ossetia Written Ossetian may be immediately recognized by its use of the Cyrillic letter Ae, a letter to be found in no other language using Cyrillic script. The father of the modern Ossetian literary language is the national poet Kosta Khetagurov (1859–1906).

An Iron literary language was established in the 18th century, written using the Cyrillic script in Russia and the Georgian script in Georgia. The first Ossetian book was published in Cyrillic in 1798, and in 1844 the alphabet was revised by a Russian scientist of Finnish-Swedish origin, Andreas Sjögren. A new alphabet based on the Latin script was made official in the 1920s, but in 1937 a revised Cyrillic alphabet was introduced, with digraphs replacing most diacritics of the 1844 alphabet.

In 1820, I. Yalguzidze published a Georgian-script alphabetic primer, adding three letters to the Georgian alphabet. The Georgian orthography receded in the 19th century, but was made official with Georgian autonomy in 1937. The "one nation – two alphabets" issue caused discontent in South Ossetia in the year 1951 demanding reunification of the script, and in 1954 Georgian was replaced with the 1937 Cyrillic alphabet.

Language usage :

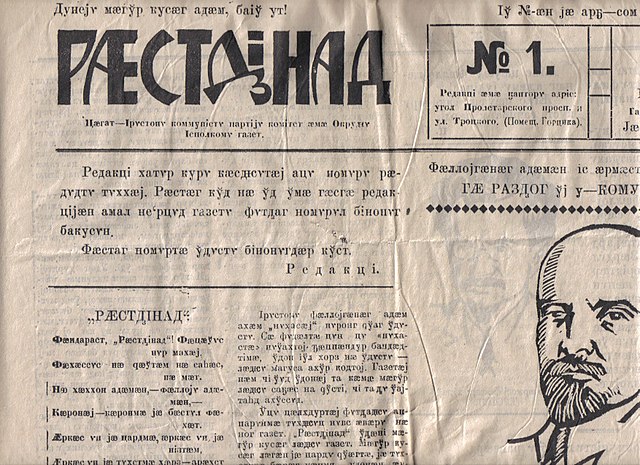

The first page of the first issue of the Ossetian newspaper R?stdzinad. Sjögren's Cyrillic alphabet. 1923 The first printed book in Ossetian appeared in 1798. The first newspaper, Iron Gazet, appeared on July 23, 1906 in Vladikavkaz.

While Ossetian is the official language in both South and North Ossetia (along with Russian), its official use is limited to publishing new laws in Ossetian newspapers. There are two daily newspapers in Ossetian: Raestdzinad ("Truth") in the North and Xurzaerin ("The Sun") in the South. Some smaller newspapers, such as district newspapers, use Ossetian for some articles. There is a monthly magazine Max dug ("Our era"), mostly devoted to contemporary Ossetian fiction and poetry.

Ossetian is taught in secondary schools for all pupils. [citation needed] Native Ossetian speakers also take courses in Ossetian literature.

The first Ossetian language Bible was published in 2010. [failed verification] It is currently the only full version of the Bible in the Ossetian language.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

||||||||||||||||||||||