| PARTHIAN EMPIRE

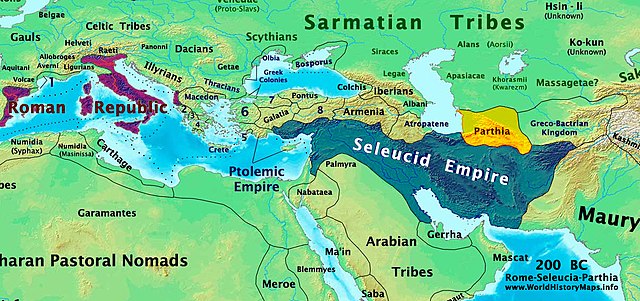

The Parthian Empire in 94 BC at its greatest extent, during the reign of Mithridates II (r. 124 – 91 BC) Parthian Empire

247 BC - 224 AD

Capital : Ctesiphon, Ecbatana, Hecatompylos, Susa, Mithradatkirt, Asaak, Rhages

Common languages : Greek (official), Parthian (official), Aramaic (lingua franca)

Religion : Zoroastrianism and Babylonian religion

Government : Feudal monarchy

Monarch

• 247 - 211 BC : Arsaces I (first)

• 208 - 224 AD : Artabanus IV (last)

Legislature : Megisthanes

Historical era : Classical antiquity

• Established : 247 BC

• Disestablished : 224 AD

Area

1 AD : 2,800,000 km2 (1,100,000 sq mi)

Currency : Drachma

Preceded by

Seleucid Empire

Succeeded by

Sasanian Empire

The Parthian Empire (247 BC - 224 AD), also known as the Arsacid Empire, was a major Iranian political and cultural power in ancient Iran.

Its latter name comes from its founder, Arsaces I, who led the Parni tribe in conquering the region of Parthia in Iran's northeast, then a satrapy (province) under Andragoras, in rebellion against the Seleucid Empire. Mithridates I (r. c. 171–132 BC) greatly expanded the empire by seizing Media and Mesopotamia from the Seleucids. At its height, the Parthian Empire stretched from the northern reaches of the Euphrates, in what is now central-eastern Turkey, to present-day Afghanistan and western Pakistan. The empire, located on the Silk Road trade route between the Roman Empire in the Mediterranean Basin and the Han dynasty of China, became a center of trade and commerce.

The Parthians largely adopted the art, architecture, religious beliefs, and royal insignia of their culturally heterogeneous empire, which encompassed Persian, Hellenistic, and regional cultures. For about the first half of its existence, the Arsacid court adopted elements of Greek culture, though it eventually saw a gradual revival of Iranian traditions. The Arsacid rulers were titled the "King of Kings", as a claim to be the heirs to the Achaemenid Empire; indeed, they accepted many local kings as vassals where the Achaemenids would have had centrally appointed, albeit largely autonomous, satraps. The court did appoint a small number of satraps, largely outside Iran, but these satrapies were smaller and less powerful than the Achaemenid potentates. With the expansion of Arsacid power, the seat of central government shifted from Nisa to Ctesiphon along the Tigris (south of modern Baghdad, Iraq), although several other sites also served as capitals.

The earliest enemies of the Parthians were the Seleucids in the west and the Scythians in the north. However, as Parthia expanded westward, they came into conflict with the Kingdom of Armenia, and eventually the late Roman Republic. Rome and Parthia competed with each other to establish the kings of Armenia as their subordinate clients. The Parthians soundly defeated Marcus Licinius Crassus at the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BC, and in 40–39 BC, Parthian forces captured the whole of the Levant except Tyre from the Romans. However, Mark Antony led a counterattack against Parthia, although his successes were generally achieved in his absence, under the leadership of his lieutenant Ventidius. Various Roman emperors or their appointed generals invaded Mesopotamia in the course of the ensuing Roman–Parthian Wars of the next few centuries. The Romans captured the cities of Seleucia and Ctesiphon on multiple occasions during these conflicts, but were never able to hold on to them. Frequent civil wars between Parthian contenders to the throne proved more dangerous to the Empire's stability than foreign invasion, and Parthian power evaporated when Ardashir I, ruler of Istakhr in Persis, revolted against the Arsacids and killed their last ruler, Artabanus IV, in 224 AD. Ardashir established the Sasanian Empire, which ruled Iran and much of the Near East until the Muslim conquests of the 7th century AD, although the Arsacid dynasty lived on through the Arsacid Dynasty of Armenia, the Arsacid dynasty of Iberia, and the Arsacid Dynasty of Caucasian Albania; all eponymous branches of the Parthian Arsacids.

Native Parthian sources, written in Parthian, Greek and other languages, are scarce when compared to Sasanian and even earlier Achaemenid sources. Aside from scattered cuneiform tablets, fragmentary ostraca, rock inscriptions, drachma coins, and the chance survival of some parchment documents, much of Parthian history is only known through external sources. These include mainly Greek and Roman histories, but also Chinese histories, prompted by the Han Chinese desire to form alliances against the Xiongnu. Parthian artwork is viewed by historians as a valid source for understanding aspects of society and culture that are otherwise absent in textual sources.

History

:

Before Arsaces I founded the Arsacid Dynasty, he was chieftain of the Parni, an ancient Central-Asian tribe of Iranian peoples and one of several nomadic tribes within the confederation of the Dahae. The Parni most likely spoke an eastern Iranian language, in contrast to the northwestern Iranian language spoken at the time in Parthia. The latter was a northeastern province, first under the Achaemenid, and then the Seleucid empires. After conquering the region, the Parni adopted Parthian as the official court language, speaking it alongside Middle Persian, Aramaic, Greek, Babylonian, Sogdian and other languages in the multilingual territories they would conquer.

Why the Arsacid court retroactively chose 247 BC as the first year of the Arsacid era is uncertain. A.D.H. Bivar concludes that this was the year the Seleucids lost control of Parthia to Andragoras, the appointed satrap who rebelled against them. Hence, Arsaces I "backdated his regnal years" to the moment when Seleucid control over Parthia ceased. However, Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis asserts that this was simply the year Arsaces was made chief of the Parni tribe. Homa Katouzian and Gene Ralph Garthwaite claim it was the year Arsaces conquered Parthia and expelled the Seleucid authorities, yet Curtis and Maria Brosius state that Andragoras was not overthrown by the Arsacids until 238 BC.

It is unclear who immediately succeeded Arsaces I. Bivar and Katouzian affirm that it was his brother Tiridates I of Parthia, who in turn was succeeded by his son Arsaces II of Parthia in 211 BC. Yet Curtis and Brosius state that Arsaces II was the immediate successor of Arsaces I, with Curtis claiming the succession took place in 211 BC, and Brosius in 217 BC. Bivar insists that 138 BC, the last regnal year of Mithridates I, is "the first precisely established regnal date of Parthian history." Due to these and other discrepancies, Bivar outlines two distinct royal chronologies accepted by historians. A fictitious claim was later made from the 2nd-century BC onwards by the Parthians, which represented them as descendants of the Achaemenid king of kings, Artaxerxes II of Persia (r. 404 – 358 BC).

For a time, Arsaces consolidated his position in Parthia and Hyrcania by taking advantage of the invasion of Seleucid territory in the west by Ptolemy III Euergetes (r. 246–222 BC) of Egypt. This conflict with Ptolemy, the Third Syrian War (246–241 BC), also allowed Diodotus I to rebel and form the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom in Central Asia. The latter's successor, Diodotus II, formed an alliance with Arsaces against the Seleucids, but Arsaces was temporarily driven from Parthia by the forces of Seleucus II Callinicus (r. 246–225 BC). After spending some time in exile among the nomadic Apasiacae tribe, Arsaces led a counterattack and recaptured Parthia. Seleucus II's successor, Antiochus III the Great (r. 222–187 BC), was unable to immediately retaliate because his troops were engaged in putting down the rebellion of Molon in Media.

Antiochus III launched a massive campaign to retake Parthia and Bactria in 210 or 209 BC. Despite some victories he was unsuccessful, but did negotiate a peace settlement with Arsaces II. The latter was granted the title of king (Greek: basileus) in return for his submission to Antiochus III as his superior. The Seleucids were unable to further intervene in Parthian affairs following increasing encroachment by the Roman Republic and the Seleucid defeat at Magnesia in 190 BC. Priapatius (r. c. 191–176 BC) succeeded Arsaces II, and Phraates I (r. c. 176–171 BC) eventually ascended the throne. Phraates I ruled Parthia without further Seleucid interference.

Expansion and consolidation :

Drachma of Mithridates I, showing him wearing a beard and a royal

diadem on his head. Reverse side: Heracles/Verethragna, holding

a club in his left hand and a cup in his right hand; Greek inscription

reading "of the Great King Arsaces the Philhellene"

Relations between Parthia and Greco-Bactria deteriorated after the death of Diodotus II, when Mithridates' forces captured two eparchies of the latter kingdom, then under Eucratides I (r. c. 170–145 BC). Turning his sights on the Seleucid realm, Mithridates invaded Media and occupied Ecbatana in 148 or 147 BC; the region had been destabilized by a recent Seleucid suppression of a rebellion there led by Timarchus. This victory was followed by the Parthian conquest of Babylonia in Mesopotamia, where Mithridates had coins minted at Seleucia in 141 BC and held an official investiture ceremony. While Mithridates retired to Hyrcania, his forces subdued the kingdoms of Elymais and Characene and occupied Susa. By this time, Parthian authority extended as far east as the Indus River.

Whereas Hecatompylos had served as the first Parthian capital, Mithridates established royal residences at Seleucia, Ecbatana, Ctesiphon and his newly founded city, Mithradatkert (Nisa, Turkmenistan), where the tombs of the Arsacid kings were built and maintained. Ecbatana became the main summertime residence for the Arsacid royalty. Ctesiphon may not have become the official capital until the reign of Gotarzes I (r. c. 90–80 BC). It became the site of the royal coronation ceremony and the representational city of the Arsacids, according to Brosius.

The Seleucids were unable to retaliate immediately as general Diodotus Tryphon led a rebellion at the capital Antioch in 142 BC. However, by 140 BC Demetrius II Nicator was able to launch a counter-invasion against the Parthians in Mesopotamia. Despite early successes, the Seleucids were defeated and Demetrius himself was captured by Parthian forces and taken to Hyrcania. There Mithridates treated his captive with great hospitality; he even married his daughter Rhodogune of Parthia to Demetrius.

Antiochus VII Sidetes (r. 138–129 BC), a brother of Demetrius, assumed the Seleucid throne and married the latter's wife Cleopatra Thea. After defeating Diodotus Tryphon, Antiochus initiated a campaign in 130 BC to retake Mesopotamia, now under the rule of Phraates II (r. c. 132–127 BC). The Parthian general Indates was defeated along the Great Zab, followed by a local uprising where the Parthian governor of Babylonia was killed. Antiochus conquered Babylonia and occupied Susa, where he minted coins. After advancing his army into Media, the Parthians pushed for peace, which Antiochus refused to accept unless the Arsacids relinquished all lands to him except Parthia proper, paid heavy tribute, and released Demetrius from captivity. Arsaces released Demetrius and sent him to Syria, but refused the other demands. By spring 129 BC, the Medes were in open revolt against Antiochus, whose army had exhausted the resources of the countryside during winter. While attempting to put down the revolts, the main Parthian force swept into the region and killed Antiochus at the Battle of Ecbatana in 129 BC. His body was sent back to Syria in a silver coffin; his son Seleucus was made a Parthian hostage and a daughter joined Phraates' harem.

Drachma of Mithridates II (r. c. 124 – 91 BC). Reverse side: seated archer carrying a bow; inscription reading "of the King of Kings Arsaces the Renowned/Manifest Philhellene." While the Parthians regained the territories lost in the west, another threat arose in the east. In 177–176 BC the nomadic confederation of the Xiongnu dislodged the nomadic Yuezhi from their homelands in what is now Gansu province in Northwest China; the Yuezhi then migrated west into Bactria and displaced the Saka (Scythian) tribes. The Saka were forced to move further west, where they invaded the Parthian Empire's northeastern borders. Mithridates was thus forced to retire to Hyrcania after his conquest of Mesopotamia.

Some of the Saka were enlisted in Phraates' forces against Antiochus. However, they arrived too late to engage in the conflict. When Phraates refused to pay their wages, the Saka revolted, which he tried to put down with the aid of former Seleucid soldiers, yet they too abandoned Phraates and joined sides with the Saka. Phraates II marched against this combined force, but he was killed in battle. The Roman historian Justin reports that his successor Artabanus I (r. c. 128–124 BC) shared a similar fate fighting nomads in the east. He claims Artabanus was killed by the Tokhari (identified as the Yuezhi), although Bivar believes Justin conflated them with the Saka.Mithridates II (r. c. 124–91 BC) later recovered the lands lost to the Saka in Sakastan.

Han-dynasty Chinese silk from Mawangdui, 2nd century BC, silk from China was perhaps the most lucrative luxury item the Parthians traded at the western end of the Silk Road Following the Seleucid withdrawal from Mesopotamia, the Parthian governor of Babylonia, Himerus, was ordered by the Arsacid court to conquer Characene, then ruled by Hyspaosines from Charax Spasinu. When this failed, Hyspaosines invaded Babylonia in 127 BC and occupied Seleucia. Yet by 122 BC, Mithridates II forced Hyspaosines out of Babylonia and made the kings of Characene vassals under Parthian suzerainty. After Mithridates extended Parthian control further west, occupying Dura-Europos in 113 BC, he became embroiled in a conflict with the Kingdom of Armenia. His forces defeated and deposed Artavasdes I of Armenia in 97 BC, taking his son Tigranes hostage, who would later become Tigranes II "the Great" of Armenia (r. c. 95–55 BC).

The Indo-Parthian Kingdom, located in modern-day Afghanistan and Pakistan made an alliance with the Parthian Empire in the 1st century BC. Bivar claims that these two states considered each other political equals. After the Greek philosopher Apollonius of Tyana visited the court of Vardanes I (r. c. 40–47 AD) in 42 AD, Vardanes provided him with the protection of a caravan as he traveled to Indo-Parthia. When Apollonius reached Indo-Parthia's capital Taxila, his caravan leader read Vardanes' official letter, perhaps written in Parthian, to an Indian official who treated Apollonius with great hospitality.

Following the diplomatic venture of Zhang Qian into Central Asia during the reign of Emperor Wu of Han (r. 141–87 BC), the Han Empire of China sent a delegation to Mithridates II's court in 121 BC. The Han embassy opened official trade relations with Parthia via the Silk Road yet did not achieve a desired military alliance against the confederation of the Xiongnu. The Parthian Empire was enriched by taxing the Eurasian caravan trade in silk, the most highly priced luxury good imported by the Romans. Pearls were also a highly valued import from China, while the Chinese purchased Parthian spices, perfumes, and fruits. Exotic animals were also given as gifts from the Arsacid to Han courts; in 87 AD Pacorus II of Parthia sent lions and Persian gazelles to Emperor Zhang of Han (r. 75–88 AD). Besides silk, Parthian goods purchased by Roman merchants included iron from India, spices, and fine leather. Caravans traveling through the Parthian Empire brought West Asian and sometimes Roman luxury glasswares to China. The merchants of Sogdia, speaking an Eastern Iranian language, served as the primary middlemen of this vital silk trade between Parthia and Han China.

Rome and Armenia :

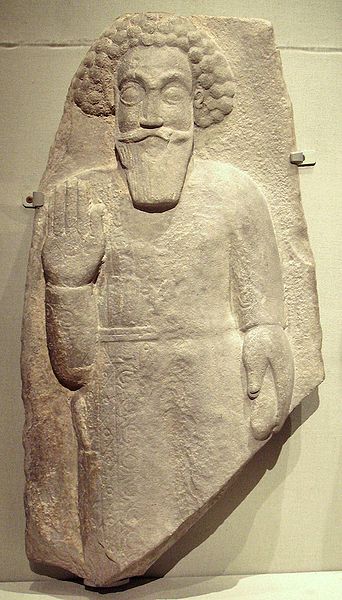

Bronze statue of a Parthian nobleman from the sanctuary at Shami

in Elymais (modern-day Khuzestan Province, Iran, along the Persian

Gulf), now located at the National Museum of Iran. Dated 50 BC-150

AD, Parthian School.

Despite this agreement, in 93 or 92 BC Parthia fought a war in Syria against the tribal leader Laodice and her Seleucid ally Antiochus X Eusebes (r. 95–92? BC), killing the latter. When one of the last Seleucid monarchs, Demetrius III Eucaerus, attempted to besiege Beroea (modern Aleppo), Parthia sent military aid to the inhabitants and Demetrius was defeated.

Following the rule of Mithridates II, his son Gotarzes I succeeded him. He reigned during a period coined in scholarship as the "Parthian Dark Age," due to the lack of clear information on the events of this period in the empire, except a series of, apparently overlapping, reigns. It is only with the beginning of the reign of Orodes II in c.?57 BC, that the line of Parthian rulers can again be reliably traced. This system of split monarchy weakened Parthia, allowing Tigranes II of Armenia to annex Parthian territory in western Mesopotamia. This land would not be restored to Parthia until the reign of Sinatruces (r. c. 78–69 BC).

Following the outbreak of the Third Mithridatic War, Mithridates VI of Pontus (r. 119–63 BC), an ally of Tigranes II of Armenia, requested aid from Parthia against Rome, but Sinatruces refused help. When the Roman commander Lucullus marched against the Armenian capital Tigranocerta in 69 BC, Mithridates VI and Tigranes II requested the aid of Phraates III (r. c. 71–58). Phraates did not send aid to either, and after the fall of Tigranocerta he reaffirmed with Lucullus the Euphrates as the boundary between Parthia and Rome.

Tigranes the Younger, son of Tigranes II of Armenia, failed to usurp the Armenian throne from his father. He fled to Phraates III and convinced him to march against Armenia's new capital at Artaxarta. When this siege failed, Tigranes the Younger once again fled, this time to the Roman commander Pompey. He promised Pompey that he would act as a guide through Armenia, but, when Tigranes II submitted to Rome as a client king, Tigranes the Younger was brought to Rome as a hostage. Phraates demanded Pompey return Tigranes the Younger to him, but Pompey refused. In retaliation, Phraates launched an invasion into Corduene (southeastern Turkey) where, according to two conflicting Roman accounts, the Roman consul Lucius Afranius forced the Parthians out by either military or diplomatic means.

Phraates III was assassinated by his sons Orodes II of Parthia and Mithridates IV of Parthia, after which Orodes turned on Mithridates, forcing him to flee from Media to Roman Syria. Aulus Gabinius, the Roman proconsul of Syria, marched in support of Mithridates to the Euphrates, but had to turn back to aid Ptolemy XII Auletes (r. 80–58; 55–51 BC) against a rebellion in Egypt. Despite losing his Roman support, Mithridates managed to conquer Babylonia, and minted coins at Seleucia until 54 BC. In that year, Orodes' general, known only as Surena after his noble family's clan name, recaptured Seleucia, and Mithridates was executed.

Marcus Licinius Crassus, one of the triumvirs, who was now proconsul of Syria, invaded Parthia in 53 BC in belated support of Mithridates. As his army marched to Carrhae (modern Harran, southeastern Turkey), Orodes II invaded Armenia, cutting off support from Rome's ally Artavasdes II of Armenia (r. 53–34 BC). Orodes persuaded Artavasdes to a marriage alliance between the crown prince Pacorus I of Parthia (d. 38 BC) and Artavasdes' sister.

Surena, with an army entirely on horseback, rode to meet Crassus. Surena's 1,000 cataphracts (armed with lances) and 9,000 horse archers were outnumbered roughly four to one by Crassus' army, comprising seven Roman legions and auxiliaries including mounted Gauls and light infantry. Using a baggage train of about 1,000 camels, the Parthian army provided the horse archers with a constant supply of arrows. The horse archers employed the "Parthian shot" tactic: feigning retreat to draw enemy out, then turning and shooting at them when exposed. This tactic, executed with heavy composite bows on the flat plain, devastated Crassus' infantry.

With some 20,000 Romans dead, approximately 10,000 captured, and roughly another 10,000 escaping west, Crassus fled into the Armenian countryside. At the head of his army, Surena approached Crassus, offering a parley, which Crassus accepted. However, he was killed when one of his junior officers, suspecting a trap, attempted to stop him from riding into Surena's camp. Crassus' defeat at Carrhae was one of the worst military defeats of Roman history. Parthia's victory cemented its reputation as a formidable if not equal power with Rome. With his camp followers, war captives, and precious Roman booty, Surena traveled some 700 km (430 mi) back to Seleucia where his victory was celebrated. However, fearing his ambitions even for the Arsacid throne, Orodes had Surena executed shortly thereafter.

Roman aurei bearing the portraits of Mark Antony (left) and Octavian

(right), issued in 41 BC to celebrate the establishment of the Second

Triumvirate by Octavian, Antony and Marcus Lepidus in 43 BC.

Quintus Labienus, a general loyal to Cassius and Brutus, sided with Parthia against the Second Triumvirate in 40 BC; the following year he invaded Syria alongside Pacorus I. The triumvir Mark Antony was unable to lead the Roman defense against Parthia due to his departure to Italy, where he amassed his forces to confront his rival Octavian and eventually conducted negotiations with him at Brundisium.

After Syria was occupied by Pacorus' army, Labienus split from the main Parthian force to invade Anatolia while Pacorus and his commander Barzapharnes invaded the Roman Levant. They subdued all settlements along the Mediterranean coast as far south as Ptolemais (modern Acre, Israel), with the lone exception of Tyre. In Judea, the pro-Roman Jewish forces of high priest Hyrcanus II, Phasael, and Herod were defeated by the Parthians and their Jewish ally Antigonus II Mattathias (r. 40–37 BC); the latter was made king of Judea while Herod fled to his fort at Masada.

Despite these successes, the Parthians were soon driven out of the Levant by a Roman counteroffensive. Publius Ventidius Bassus, an officer under Mark Antony, defeated and then executed Labienus at the Battle of the Cilician Gates (in modern Mersin Province, Turkey) in 39 BC. Shortly afterward, a Parthian force in Syria led by general Pharnapates was defeated by Ventidius at the Battle of Amanus Pass.

As a result, Pacorus I temporarily withdrew from Syria. When he returned in the spring of 38 BC, he faced Ventidius at the Battle of Mount Gindarus, northeast of Antioch. Pacorus was killed during the battle, and his forces retreated across the Euphrates. His death spurred a succession crisis in which Orodes II chose Phraates IV (r. c. 38–2 BC) as his new heir.

Drachma of Phraates IV (r. c. 38–2 BC). Inscription reading "of the King of Kings Arsaces the Renowned/Manifest Benefactor Philhellene" Upon assuming the throne, Phraates IV eliminated rival claimants by killing and exiling his own brothers. One of them, Monaeses, fled to Antony and convinced him to invade Parthia. Antony defeated Parthia's Judaean ally Antigonus in 37 BC, installing Herod as a client king in his place.

The following year, when Antony marched to Theodosiopolis, Artavasdes II of Armenia once again switched alliances by sending Antony additional troops. Antony invaded Media Atropatene (modern Iranian Azerbaijan), then ruled by Parthia's ally Artavasdes I of Media Atropatene, with the intention of seizing the capital Praaspa, the location of which is now unknown. However, Phraates IV ambushed Antony's rear detachment, destroying a giant battering ram meant for the siege of Praaspa; after this, Artavasdes II abandoned Antony's forces.

The Parthians pursued and harassed Antony's army as it fled to Armenia. Eventually, the greatly weakened force reached Syria. Antony lured Artavasdes II into a trap with the promise of a marriage alliance. He was taken captive in 34 BC, paraded in Antony's mock Roman triumph in Alexandria, Egypt, and eventually executed by Cleopatra VII of the Ptolemaic Kingdom.

Antony attempted to strike an alliance with Artavasdes I of Media Atropatene, whose relations with Phraates IV had recently soured. This was abandoned when Antony and his forces withdrew from Armenia in 33 BC; they escaped a Parthian invasion while Antony's rival Octavian attacked his forces to the west. After the defeat and suicides of Antony and Cleopatra in 30 BC, Parthian ally Artaxias II reassumed the throne of Armenia.

Peace

with Rome, court intrigue and contact with Chinese generals :

Around this time, Tiridates II of Parthia briefly overthrew Phraates IV, who was able to quickly reestablish his rule with the aid of Scythian nomads. Tiridates fled to the Romans, taking one of Phraates' sons with him. In negotiations conducted in 20 BC, Phraates arranged for the release of his kidnapped son. In return, the Romans received the lost legionary standards taken at Carrhae in 53 BC, as well as any surviving prisoners of war. The Parthians viewed this exchange as a small price to pay to regain the prince. Augustus hailed the return of the standards as a political victory over Parthia; this propaganda was celebrated in the minting of new coins, the building of a new temple to house the standards, and even in fine art such as the breastplate scene on his statue Augustus of Prima Porta.

A close-up view of the breastplate on the statue of Augustus of Prima Porta, showing a Parthian man returning to Augustus the legionary standards lost by Marcus Licinius Crassus at Carrhae Along with the prince, Augustus also gave Phraates IV an Italian slave-girl, who later became Queen Musa of Parthia. To ensure that her child Phraataces would inherit the throne without incident, Musa convinced Phraates IV to give his other sons to Augustus as hostages. Again, Augustus used this as propaganda depicting the submission of Parthia to Rome, listing it as a great accomplishment in his Res Gestae Divi Augusti. When Phraataces took the throne as Phraates V (r. c. 2 BC – 4 AD), Musa married ruled alongside him. The Parthian nobility, disapproving of the notion of a king with non-Arsacid blood, forced the pair into exile in Roman territory. Phraates' successor Orodes III of Parthia lasted just two years on the throne, and was followed by Vonones I, who had adopted many Roman mannerisms during time in Rome. The Parthian nobility, angered by Vonones' sympathies for the Romans, backed a rival claimant, Artabanus II of Parthia (r. c. 10–38 AD), who eventually defeated Vonones and drove him into exile in Roman Syria.

During the reign of Artabanus II, two Jewish commoners and brothers, Anilai and Asinai from Nehardea (near modern Fallujah, Iraq), led a revolt against the Parthian governor of Babylonia. After defeating the latter, the two were granted the right to govern the region by Artabanus II, who feared further rebellion elsewhere. Anilai's Parthian wife poisoned Asinai out of fear he would attack Anilai over his marriage to a gentile.

Following this, Anilai became embroiled in an armed conflict with a son-in-law of Artabanus, who eventually defeated him. With the Jewish regime removed, the native Babylonians began to harass the local Jewish community, forcing them to emigrate to Seleucia. When that city rebelled against Parthian rule in 35–36 AD, the Jews were expelled again, this time by the local Greeks and Aramaeans. The exiled Jews fled to Ctesiphon, Nehardea, and Nisibis.

A denarius struck in 19 BC during the reign of Augustus, with the

goddess Feronia depicted on the obverse, and on the reverse a Parthian

man kneeling in submission while offering the Roman military standards

taken at the Battle of Carrhae.

In 97 AD, the Chinese general Ban Chao, the Protector-General of the Western Regions, sent his emissary Gan Ying on a diplomatic mission to reach the Roman Empire. Gan visited the court of Pacorus II at Hecatompylos before departing towards Rome. He traveled as far west as the Persian Gulf, where Parthian authorities convinced him that an arduous sea voyage around the Arabian Peninsula was the only means to reach Rome. Discouraged by this, Gan Ying returned to the Han court and provided Emperor He of Han (r. 88–105 AD) with a detailed report on the Roman Empire based on oral accounts of his Parthian hosts. William Watson speculates that the Parthians would have been relieved at the failed efforts by the Han Empire to open diplomatic relations with Rome, especially after Ban Chao's military victories against the Xiongnu in eastern Central Asia. However, Chinese records maintain that a Roman embassy, perhaps only a group of Roman merchants, arrived at the Han capital Luoyang by way of Jiaozhi (northern Vietnam) in 166 AD, during the reigns of Marcus Aurelius (r. 161–180 AD) and Emperor Huan of Han (r. 146–168 AD). Although it could be coincidental, Antonine Roman golden medallions dated to the reigns of Marcus Aurelius and his predecessor Antoninus Pius have been discovered at Oc Eo, Vietnam (among other Roman artefacts in the Mekong Delta), a site that is one of the suggested locations for the port city of "Cattigara" along the Magnus Sinus (i.e. Gulf of Thailand and South China Sea) in Ptolemy's Geography.

Continuation of Roman hostilities and Parthian decline :

Map of the troop movements during the first two years of the Roman–Parthian War of 58–63 AD over the Kingdom of Armenia, detailing the Roman offensive into Armenia and capture of the country by Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo.

Parthian king making an offering to god Herakles-Verethragna. Masdjid-e Suleiman, Iran. 2nd-3rd century AD. Louvre Museum Sb 7302 After the Iberian king Pharasmanes I had his son Rhadamistus (r. 51–55 AD) invade Armenia to depose the Roman client king Mithridates, Vologases I of Parthia (r. c. 51–77 AD) planned to invade and place his brother, the later Tiridates I of Armenia, on the throne. Rhadamistus was eventually driven from power, and, beginning with the reign of Tiridates, Parthia would retain firm control over Armenia—with brief interruptions—through the Arsacid Dynasty of Armenia. Even after the fall of the Parthian Empire, the Arsacid line lived on through the Armenian kings. However, not only did the Arsacid line continue through the Armenians, it as well continued through the Georgian kings with the Arsacid dynasty of Iberia, and for many centuries afterwards in Caucasian Albania through the Arsacid Dynasty of Caucasian Albania.

When Vardanes II of Parthia rebelled against his father Vologases I in 55 AD, Vologases withdrew his forces from Armenia. Rome quickly attempted to fill the political vacuum left behind. In the Roman–Parthian War of 58–63 AD, the commander Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo achieved some military successes against the Parthians while installing Tigranes VI of Armenia as a Roman client. However, Corbulo's successor Lucius Caesennius Paetus was soundly defeated by Parthian forces and fled Armenia. Following a peace treaty, Tiridates I traveled to Naples and Rome in 63 AD. At both sites the Roman emperor Nero (r. 54–68 AD) ceremoniously crowned him king of Armenia by placing the royal diadem on his head.

A long period of peace between Parthia and Rome ensued, with only the invasion of Alans into Parthia's eastern territories around 72 AD mentioned by Roman historians. Whereas Augustus and Nero had chosen a cautious military policy when confronting Parthia, later Roman emperors invaded and attempted to conquer the eastern Fertile Crescent, the heart of the Parthian Empire along the Tigris and Euphrates. The heightened aggression can be explained in part by Rome's military reforms. To match Parthia's strength in missile troops and mounted warriors, the Romans at first used foreign allies (especially Nabataeans), but later established a permanent auxilia force to complement their heavy legionary infantry. The Romans eventually maintained regiments of horse archers (sagittarii) and even mail-armored cataphracts in their eastern provinces. Yet the Romans had no discernible grand strategy in dealing with Parthia and gained very little territory from these invasions. The primary motivations for war were the advancement of the personal glory and political position of the emperor, as well as defending Roman honor against perceived slights such as Parthian interference in the affairs of Rome's client states.

Rock relief of Parthian king at Behistun, most likely Vologases III (r. c. 110 – 147 AD) Hostilities between Rome and Parthia were renewed when Osroes I of Parthia (r. c. 109–128 AD) deposed the Armenian king Sanatruk and replaced him with Axidares, son of Pacorus II, without consulting Rome. The Roman emperor Trajan (r. 98–117 AD) had the next Parthian nominee for the throne, Parthamasiris, killed in 114 AD, instead making Armenia a Roman province. His forces, led by Lusius Quietus, also captured Nisibis; its occupation was essential to securing all the major routes across the northern Mesopotamian plain. The following year, Trajan invaded Mesopotamia and met little resistance from only Meharaspes of Adiabene, since Osroes was engaged in a civil war to the east with Vologases III of Parthia. Trajan spent the winter of 115–116 at Antioch, but resumed his campaign in the spring. Marching down the Euphrates, he captured Dura-Europos, the capital Ctesiphon and Seleucia, and even subjugated Characene, where he watched ships depart to India from the Persian Gulf.

In the last months of 116 AD, Trajan captured the Persian city of Susa. When Sanatruces II of Parthia gathered forces in eastern Parthia to challenge the Romans, his cousin Parthamaspates of Parthia betrayed and killed him: Trajan crowned him the new king of Parthia. Never again would the Roman Empire advance so far to the east. On Trajan's return north, the Babylonian settlements revolted against the Roman garrisons. Trajan was forced to retreat from Mesopotamia in 117 AD, overseeing a failed siege of Hatra during his withdrawal. His retreat was—in his intentions—temporary, because he wanted to renew the attack on Parthia in 118 AD and "make the subjection of the Parthians a reality," but Trajan died suddenly in August 117 AD. During his campaign, Trajan was granted the title Parthicus by the Senate and coins were minted proclaiming the conquest of Parthia. However, only the 4th-century AD historians Eutropius and Festus allege that he attempted to establish a Roman province in lower Mesopotamia.

A Parthian (right) wearing a Phrygian cap, depicted as a prisoner of war in chains held by a Roman (left); Arch of Septimius Severus, Rome, 203 AD Trajan's successor Hadrian (r. 117–138 AD) reaffirmed the Roman-Parthian border at the Euphrates, choosing not to invade Mesopotamia due to Rome's now limited military resources. Parthamaspates fled after the Parthians revolted against him, yet the Romans made him king of Osroene. Osroes I died during his conflict with Vologases III, the latter succeeded by Vologases IV of Parthia (r. c. 147–191 AD) who ushered in a period of peace and stability. However, the Roman–Parthian War of 161–166 AD began when Vologases invaded Armenia and Syria, retaking Edessa. Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius (r. 161–180 AD) had co-ruler Lucius Verus (r. 161–169 AD) guard Syria while Marcus Statius Priscus invaded Armenia in 163 AD, followed by the invasion of Mesopotamia by Avidius Cassius in 164 AD. The Romans captured and burnt Seleucia and Ctesiphon to the ground, yet they were forced to retreat once the Roman soldiers contracted a deadly disease (possibly smallpox) that soon ravaged the Roman world. Although they withdrew, from this point forward the city of Dura-Europos remained in Roman hands. When Roman emperor Septimius Severus (r. 193–211 AD) invaded Mesopotamia in 197 AD during the reign of Vologases V of Parthia (r. c. 191–208 AD), the Romans once again marched down the Euphrates and captured Seleucia and Ctesiphon. After assuming the title Parthicus Maximus, he retreated in late 198 AD, failing as Trajan once did to capture Hatra during a siege.

Around

212 AD, soon after Vologases VI of Parthia (r. c. 208–222

AD) took the throne, his brother Artabanus IV of Parthia (d. 224

AD) rebelled against him and gained control over a greater part

of the empire.

The Parthian Empire, weakened by internal strife and wars with Rome, was soon to be followed by the Sasanian Empire. Indeed, shortly afterward, Ardashir I, the local Iranian ruler of Persis (modern Fars Province, Iran) from Istakhr began subjugating the surrounding territories in defiance of Arsacid rule. He confronted Artabanus IV at the Battle of Hormozdgan on 28 April 224 AD, perhaps at a site near Isfahan, defeating him and establishing the Sasanian Empire. There is evidence, however, that suggests Vologases VI continued to mint coins at Seleucia as late as 228 AD.

The Sassanians would not only assume Parthia's legacy as Rome's Persian nemesis, but they would also attempt to restore the boundaries of the Achaemenid Empire by briefly conquering the Levant, Anatolia, and Egypt from the Eastern Roman Empire during the reign of Khosrau II (r. 590–628 AD). However, they would lose these territories to Heraclius—the last Roman emperor before the Arab conquests. Nevertheless, for a period of more than 400 years, they succeeded the Parthian realm as Rome's principal rival.

Native and external sources :

Parthian gold jewelry items found at a burial site in Nineveh (near modern Mosul, Iraq) in the British Museum Local and foreign written accounts, as well as non-textual artifacts, have been used to reconstruct Parthian history. Although the Parthian court maintained records, the Parthians had no formal study of history; the earliest universal history of Iran, the Khwaday-Namag, was not compiled until the reign of the last Sasanian ruler Yazdegerd III (r. 632–651 AD). Indigenous sources on Parthian history remain scarce, with fewer of them available than for any other period of Iranian history. Most contemporary written records on Parthia contain Greek as well as Parthian and Aramaic inscriptions. The Parthian language was written in a distinct script derived from the Imperial Aramaic chancellery script of the Achaemenids, and later developed into the Pahlavi writing system.

A Sarmatian-Parthian gold necklace and amulet, 2nd century AD. Located in Tamoikin Art Fund The most valuable indigenous sources for reconstructing an accurate chronology of Arsacid rulers are the metal drachma coins issued by each ruler. These represent a "transition from non-textual to textual remains," according to historian Geo Widengren. Other Parthian sources used for reconstructing chronology include cuneiform astronomical tablets and colophons discovered in Babylonia. Indigenous textual sources also include stone inscriptions, parchment and papyri documents, and pottery ostraca. For example, at the early Parthian capital of Mithradatkert/Nisa in Turkmenistan, large caches of pottery ostraca have been found yielding information on the sale and storage of items like wine. Along with parchment documents found at sites like Dura-Europos, these also provide valuable information on Parthian governmental administration, covering issues such as taxation, military titles, and provincial organization.

Parthian golden necklace, 2nd century AD, Iran, Reza Abbasi Museum

A Parthian ceramic oil lamp, Khuzestan Province, Iran, National Museum of Iran The Greek and Latin histories, which represent the majority of materials covering Parthian history, are not considered entirely reliable since they were written from the perspective of rivals and wartime enemies. These external sources generally concern major military and political events, and often ignore social and cultural aspects of Parthian history. The Romans usually depicted the Parthians as fierce warriors but also as a culturally refined people; recipes for Parthian dishes in the cookbook Apicius exemplifies their admiration for Parthian cuisine.Apollodorus of Artemita and Arrian wrote histories focusing on Parthia, which are now lost and survive only as quoted extracts in other histories. Isidore of Charax, who lived during the reign of Augustus, provides an account of Parthian territories, perhaps from a Parthian government survey. To a lesser extent, people and events of Parthian history were also included in the histories of Justin, Strabo, Diodorus Siculus, Plutarch, Cassius Dio, Appian, Josephus, Pliny the Elder, and Herodian.

Parthian history can also be reconstructed via the Chinese historical records of events. In contrast to Greek and Roman histories, the early Chinese histories maintained a more neutral view when describing Parthia, although the habit of Chinese chroniclers to copy material for their accounts from older works (of undetermined origin) makes it difficult to establish a chronological order of events. The Chinese called Parthia Anxi, perhaps after the Greek name for the Parthian city Antiochia in Margiana. However, this could also have been a transliteration of "Arsaces", after the dynasty's eponymous founder. The works and historical authors include the Shiji (also known as the Records of the Grand Historian) by Sima Qian, the Han shu (Book of Han) by Ban Biao, Ban Gu, and Ban Zhao, and the Hou Han shu (Book of Later Han) by Fan Ye. They provide information on the nomadic migrations leading up to the early Saka invasion of Parthia and valuable political and geographical information. For example, the Shiji (ch. 123) describes diplomatic exchanges, exotic gifts given by Mithridates II to the Han court, types of agricultural crops grown in Parthia, production of wine using grapes, itinerant merchants, and the size and location of Parthian territory. The Shiji also mentions that the Parthians kept records by "writing horizontally on strips of leather," that is, parchment.

Government

and administration :

Coin of Kamnaskires III, king of Elymais (modern Khuzestan Province), and his wife Queen Anzaze, 1st century BC Compared with the earlier Achaemenid Empire, the Parthian government was notably decentralized. An indigenous historical source reveals that territories overseen by the central government were organized in a similar manner to the Seleucid Empire. They both had a threefold division for their provincial hierarchies: the Parthian marzban, xšatrap, and dizpat, similar to the Seleucid satrapy, eparchy, and hyparchy. The Parthian Empire also contained several subordinate semi-autonomous kingdoms, including the states of Caucasian Iberia, Armenia, Atropatene, Gordyene, Adiabene, Edessa, Hatra, Mesene, Elymais, and Persis. The state rulers governed their own territories and minted their own coinage distinct from the royal coinage produced at the imperial mints. This was not unlike the earlier Achaemenid Empire, which also had some city-states, and even distant satrapies who were semi-independent but "recognised the supremacy of the king, paid tribute and provided military support", according to Brosius. However, the satraps of Parthian times governed smaller territories, and perhaps had less prestige and influence than their Achaemenid predecessors. During the Seleucid period, the trend of local ruling dynasties with semi-autonomous rule, and sometimes outright rebellious rule, became commonplace, a fact reflected in the later Parthian style of governance.

Nobility :

The King of Kings headed the Parthian government. He maintained polygamous relations, and was usually succeeded by his first-born son. Like the Ptolemies of Egypt, there is also record of Arsacid kings marrying their nieces and perhaps even half-sisters; Queen Musa married her own son, though this was an extreme and isolated case. Brosius provides an extract from a letter written in Greek by King Artabanus II in 21 AD, which addresses the governor (titled "archon") and citizens of the city of Susa. Specific government offices of Preferred Friend, Bodyguard and Treasurer are mentioned and the document also proves that "while there were local jurisdictions and proceedings to appointment to high office, the king could intervene on behalf of an individual, review a case and amend the local ruling if he considered it appropriate."

The hereditary titles of the hierarchic nobility recorded during the reign of the first Sasanian monarch Ardashir I most likely reflect the titles already in use during the Parthian era. There were three distinct tiers of nobility, the highest being the regional kings directly below the King of Kings, the second being those related to the King of Kings only through marriage, and the lowest order being heads of local clans and small territories.

By the 1st century AD, the Parthian nobility had assumed great power and influence in the succession and deposition of Arsacid kings. Some of the nobility functioned as court advisers to the king, as well as holy priests. Strabo, in his Geographica, preserved a claim by the Greek philosopher and historian Poseidonius that the Council of Parthia consisted of noble kinsmen and magi, two groups from which "the kings were appointed." Of the great noble Parthian families listed at the beginning of the Sassanian period, only two are explicitly mentioned in earlier Parthian documents: the House of Suren and the House of Karen. The historian Plutarch noted that members of the Suren family, the first among the nobility, were given the privilege of crowning each new Arsacid King of Kings during their coronations.

Military

:

Parthian horse archer, now on display at the Palazzo Madama, Turin

Parthian cataphract fighting a lion

Relief of an infantryman, from Zahhak Castle, Iran

The combination of horse archers and cataphracts formed an effective

backbone for the Parthian military.

The size of the Parthian army is unknown, as is the size of the empire's overall population. However, archaeological excavations in former Parthian urban centers reveal settlements which could have sustained large populations and hence a great resource in manpower. Dense population centers in regions like Babylonia were no doubt attractive to the Romans, whose armies could afford to live off the land.

Currency

:

Society

and culture :

Coin of Mithridates II of Parthia. The clothing is Parthian, while the style is Hellenistic (sitting on an omphalos). The Greek inscription reads "King Arsaces, the philhellene" Although Greek culture of the Seleucids was widely adopted by peoples of the Near East during the Hellenistic period, the Parthian era witnessed an Iranian cultural revival in religion, the arts, and even clothing fashions.Conscious of both the Hellenistic and Persian cultural roots of their kingship, the Arsacid rulers styled themselves after the Persian King of Kings and affirmed that they were also philhellenes ("friends of the Greeks"). The word "philhellene" was inscribed on Parthian coins until the reign of Artabanus II. The discontinuation of this phrase signified the revival of Iranian culture in Parthia. Vologases I was the first Arsacid ruler to have the Parthian script and language appear on his minted coins alongside the now almost illegible Greek. However, the use of Greek-alphabet legends on Parthian coins remained until the collapse of the empire.

A ceramic Parthian water spout in the shape of a man's head, dated 1st or 2nd century AD Greek cultural influence did not disappear from the Parthian Empire, however, and there is evidence that the Arsacids enjoyed Greek theatre. When the head of Crassus was brought to Orodes II, he, alongside Armenian king Artavasdes II, were busy watching a performance of The Bacchae by the playwright Euripides (c. 480–406 BC). The producer of the play decided to use Crassus' actual severed head in place of the stage-prop head of Pentheus.

On his coins, Arsaces I is depicted in apparel similar to Achaemenid satraps. According to A. Shahbazi, Arsaces "deliberately diverges from Seleucid coins to emphasize his nationalistic and royal aspirations, and he calls himself Karny/Karny (Greek: Autocrator), a title already borne by Achaemenid supreme generals, such as Cyrus the Younger." In line with Achaemenid traditions, rock-relief images of Arsacid rulers were carved at Mount Behistun, where Darius I of Persia (r. 522–486 BC) made royal inscriptions. Moreover, the Arsacids claimed familial descent from Artaxerxes II of Persia (r. 404–358 BC) as a means to bolster their legitimacy in ruling over former Achaemenid territories, i.e. as being "legitimate successors of glorious kings" of ancient Iran. Artabanus II named one of his sons Darius and laid claim to Cyrus' heritage. The Arsacid kings chose typical Zoroastrian names for themselves and some from the "heroic background" of the Avesta, according to V.G. Lukonin. The Parthians also adopted the use of the Babylonian calendar with names from the Achaemenid Iranian calendar, replacing the Macedonian calendar of the Seleucids.

Religion :

Parthian votive relief from Khuzestan Province, Iran, 2nd century AD The Parthian Empire, being culturally and politically heterogeneous, had a variety of religious systems and beliefs, the most widespread being those dedicated to Greek and Iranian cults. Aside from a minority of Jews and early Christians, most Parthians were polytheistic. Greek and Iranian deities were often blended together as one. For example, Zeus was often equated with Ahura Mazda, Hades with Angra Mainyu, Aphrodite and Hera with Anahita, Apollo with Mithra, and Hermes with Shamash. Aside from the main gods and goddesses, each ethnic group and city had their own designated deities. As with Seleucid rulers, Parthian art indicates that the Arsacid kings viewed themselves as gods; this cult of the ruler was perhaps the most widespread.

The extent of Arsacid patronage of Zoroastrianism is debated in modern scholarship. The followers of Zoroaster would have found the bloody sacrifices of some Parthian-era Iranian cults to be unacceptable. However, there is evidence that Vologases I encouraged the presence of Zoroastrian magi priests at court and sponsored the compilation of sacred Zoroastrian texts which later formed the Avesta. The Sasanian court would later adopt Zoroastrianism as the official state religion of the empire.

Although Mani (216–276 AD), the founding prophet of Manichaeism, did not proclaim his first religious revelation until 228/229 AD, Bivar asserts that his new faith contained "elements of Mandaean belief, Iranian cosmogony, and even echoes of Christianity ... [it] may be regarded as a typical reflection of the mixed religious doctrines of the late Arsacid period, which the Zoroastrian orthodoxy of the Sasanians was soon to sweep away."

There is scant archaeological evidence for the spread of Buddhism from the Kushan Empire into Iran proper. However, it is known from Chinese sources that An Shigao (fl. 2nd century AD), a Parthian nobleman and Buddhist monk, traveled to Luoyang in Han China as a Buddhist missionary and translated several Buddhist canons into Chinese.

Art and architecture :

The Parthian Temple of Charyios in Uruk Parthian art can be divided into three geo-historical phases: the art of Parthia proper; the art of the Iranian plateau; and the art of Parthian Mesopotamia. The first genuine Parthian art, found at Mithridatkert/Nisa, combined elements of Greek and Iranian art in line with Achaemenid and Seleucid traditions. In the second phase, Parthian art found inspiration in Achaemenid art, as exemplified by the investiture relief of Mithridates II at Mount Behistun. The third phase occurred gradually after the Parthian conquest of Mesopotamia.

Common motifs of the Parthian period include scenes of royal hunting expeditions and the investiture of Arsacid kings. Use of these motifs extended to include portrayals of local rulers. Common art mediums were rock-reliefs, frescos, and even graffiti. Geometric and stylized plant patterns were also used on stucco and plaster walls. The common motif of the Sasanian period showing two horsemen engaged in combat with lances first appeared in the Parthian reliefs at Mount Behistun.

In portraiture the Parthians favored and emphasized frontality, meaning the person depicted by painting, sculpture, or raised-relief on coins faced the viewer directly instead of showing his or her profile. Although frontality in portraiture was already an old artistic technique by the Parthian period, Daniel Schlumberger explains the innovation of Parthian frontality:

'Parthian frontality', as we are now accustomed to call it, deeply differs both from ancient Near Eastern and from Greek frontality, though it is, no doubt, an offspring of the latter. For both in Oriental art and in Greek art, frontality was an exceptional treatment: in Oriental art it was a treatment strictly reserved for a small number of traditional characters of cult and myth; in Greek art it was an option resorted to only for definite reasons, when demanded by the subject, and, on the whole, seldom made use of. With Parthian art, on the contrary, frontality becomes the normal treatment of the figure. For the Parthians frontality is really nothing but the habit of showing, in relief and in painting, all figures full-face, even at the expense (as it seems to us moderns) of clearness and intelligibility. So systematic is this use that it amounts to a complete banishment de facto of the side-view and of all intermediate attitudes. This singular state of things seems to have become established in the course of the 1st century A.D.

A wall mural depicting a scene from the Book of Esther at the Dura-Europos synagogue, dated 245 AD, which Curtis and Schlumberger describe as a fine example of 'Parthian frontality' Parthian art, with its distinct use of frontality in portraiture, was lost and abandoned with the profound cultural and political changes brought by the Sasanian Empire. However, even after the Roman occupation of Dura-Europos in 165 AD, the use of Parthian frontality in portraiture continued to flourish there. This is exemplified by the early 3rd-century AD wall murals of the Dura-Europos synagogue, a temple in the same city dedicated to Palmyrene gods, and the local Mithraeum.

Parthian architecture adopted elements of Achaemenid and Greek architecture, but remained distinct from the two. The style is first attested at Mithridatkert/Nisa. The Round Hall of Nisa is similar to Hellenistic palaces, but different in that it forms a circle and vault inside a square space. However, the artwork of Nisa, including marble statues and the carved scenes on ivory rhyton vessels, is unquestionably influenced by Greek art.

A signature feature of Parthian architecture was the iwan, an audience hall supported by arches or barrel vaults and open on one side. Use of the barrel vault replaced the Hellenic use of columns to support roofs. Although the iwan was known during the Achaemenid period and earlier in smaller and subterranean structures, it was the Parthians who first built them on a monumental scale. The earliest Parthian iwans are found at Seleucia, built in the early 1st century AD. Monumental iwans are also commonly found in the ancient temples of Hatra and perhaps modeled on the Parthian style. The largest Parthian iwans at that site have a span of 15 m (50 ft).

Clothing and apparel :

A sculpted head (broken off from a larger statue) of a Parthian soldier wearing a Hellenistic-style helmet, from the Parthian royal residence and necropolis of Nisa, Turkmenistan, 2nd century BC The typical Parthian riding outfit is exemplified by the famous bronze statue of a Parthian nobleman found at Shami, Elymais. Standing 1.9 m (6 ft), the figure wears a V-shaped jacket, a V-shaped tunic fastened in place with a belt, loose-fitting and many-folded trousers held by garters, and a diadem or band over his coiffed, bobbed hair.His outfit is commonly seen in relief images of Parthian coins by the mid-1st century BC.

Examples of clothing in Parthian inspired sculptures have been found in excavations at Hatra, in northwestern Iraq. Statues erected there feature the typical Parthian shirt (qamis), combined with trousers and made with fine, ornamented materials. The aristocratic elite of Hatra adopted the bobbed hairstyles, headdresses, and belted tunics worn by the nobility belonging to the central Arsacid court. The trouser-suit was even worn by the Arsacid kings, as shown on the reverse images of coins. The Parthian trouser-suit was also adopted in Palmyra, Syria, along with the use of Parthian frontality in art.

Parthian sculptures depict wealthy women wearing long-sleeved robes over a dress, with necklaces, earrings, bracelets, and headdresses bedecked in jewelry. Their many-folded dresses were fastened by a brooch at one shoulder. Their headdresses also featured a veil which was draped backwards.

As seen in Parthian coinage, the headdresses worn by the Parthian kings changed over time. The earliest Arsacid coins show rulers wearing the soft cap with cheek flaps, known as the bashlyk (Greek: kyrbasia). This may have derived from an Achaemenid-era satrapal headdress and the pointy hats depicted in the Achaemenid reliefs at Behistun and Persepolis. The earliest coins of Mithridates I show him wearing the soft cap, yet coins from the latter part of his reign show him for the first time wearing the royal Hellenistic diadem. Mithridates II was the first to be shown wearing the Parthian tiara, embroidered with pearls and jewels, a headdress commonly worn in the late Parthian period and by Sasanian monarchs.

Language

:

Writing and literature :

Parthian long-necked lute, c. 3 BC – 3 AD It is known that during the Parthian period the court minstrel (gosan) recited poetic oral literature accompanied by music. However, their stories, composed in verse form, were not written down until the subsequent Sassanian period. In fact, there is no known Parthian-language literature that survives in original form; all of the surviving texts were written down in the following centuries. It is believed that such stories as the romantic tale Vis and Ramin and epic cycle of the Kayanian dynasty were part of the corpus of oral literature from Parthian times, although compiled much later. Although literature of the Parthian language was not committed to written form, there is evidence that the Arsacids acknowledged and respected written Greek literature.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

,_Nisa_mint.jpg)

,_Ray_mint.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)