| PRAKRIT

Word for "Prakrit" (here Pra-kr-te) in Late Brahmi script in the Mandsaur stone inscription of Yashodharman-Vishnuvardhana, 532 CE Prakrit

:

Indo-European

The Prakrits (Shaurseni: paud; Jain Prakrit: pau; Kannada: pagad) are a group of vernacular Middle Indo-Aryan languages used in India from around the 3rd century BCE to the 8th century CE. The term Prakrit is usually applied to the middle period of Middle Indo-Aryan languages, excluding earlier inscriptions and the later Pali. The Prakrits were used contemporaneously with the prestigious Classical Sanskrit of higher social classes. Prakrta literally means "natural", as opposed to samskrt, which literally means "constructed" or "refined".

Etymology

:

Definition :

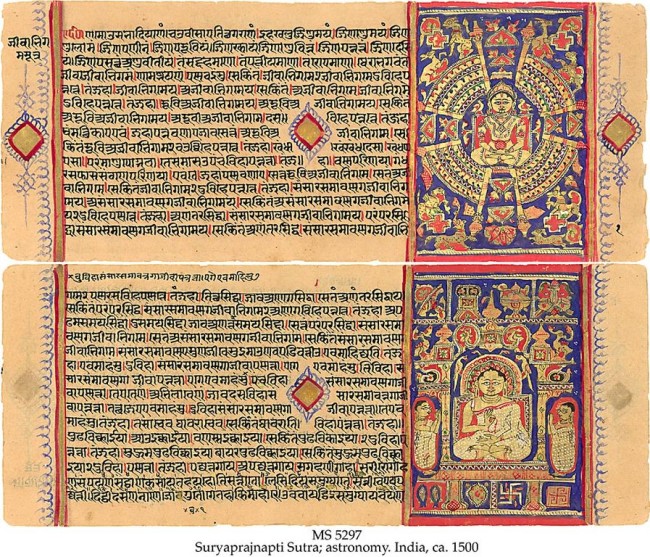

The Suryaprajñaptisutra, an astronomical work written in Jain Prakrit language (in Devanagari book script), c. 1500

Sanskrit's link to the Prakrit languages and other Indo-European languages To view large image Click here.

Modern scholars have used the term "Prakrit" to refer to two concepts :

•

Prakrit languages

: a group of closely related literary languages

The broadest definition uses the term "Prakrit" to describe any Middle Indo-Aryan language that deviates from Sanskrit in any manner. American scholar Andrew Ollett points out that this unsatisfactory definition makes "Prakrit" a cover term for languages that were not actually called Prakrit in ancient India, such as :

•

Ashokan Prakrit:

the language of Ashok's inscriptions

• Scenic Prakrits :

• Primary Prakrits :

According to Sanskrit scholar A. C. Woolner, the Ardhamagadhi (or simply Magadhi) Prakrit, which was used extensively to write the scriptures of Jainism, is often considered to be the definitive form of Prakrit, while others are considered variants of it. Prakrit grammarians would give the full grammar of Ardhamagadhi first, and then define the other grammars with relation to it. For this reason, courses teaching 'Prakrit' are often regarded as teaching Ardhamagadhi.

Grammar

:

German Indologist Theodor Bloch (1894) dismissed the medieval Prakrit grammarians as unreliable, arguing that they were not qualified to describe the language of the texts composed centuries before them. Other scholars such as Sten Konow, Richard Pischel and Alfred Hillebrandt, disagree with Bloch. It is possible that the grammarians sought to codify only the language of the earliest classics of the Prakrit literature, such as the Gah Sattasai. Another explanation is that the extant Prakrit manuscripts contain scribal errors. Most of the surviving Prakrit manuscripts were produced in a variety of regional scripts, during 1300-1800 CE. It appears that the scribes who made these copies from the earlier manuscripts did not have a good command of the original language of the texts, as several of the extant Prakrit texts contain inaccuracies or are incomprehensible.

Prakrit Prakash, a book attributed to Vararuchi, summarizes various Prakrit languages .

Prevalence

:

Prakrit is often wrongly assumed to have been a language (or languages) spoken by the common people, because it is different from Sanskrit, which is the predominant language of the ancient Indian literature. Several modern scholars, such as George Abraham Grierson and Richard Pischel, have asserted that the literary Prakrit does not represent the actual languages spoken by the common people of ancient India. This theory is corroborated by a market scene in Uddyotana's Kuvalaya-mala (779 CE), in which the narrator speaks a few words in 18 different languages: some of these languages sound similar to the languages spoken in modern India; but none of them resemble the language that Uddyotana identifies as "Prakrit" and uses for narration throughout the text.

Literature

:

During a large period of the first millennium, literary Prakrit was the preferred language for the fictional romance in India. Its use as a language of systematic knowledge was limited, because of Sanskrit's dominance in this area, but nevertheless, Prakrit texts exist on topics such as grammar, lexicography, metrics, alchemy, medicine, divination, and gemology. In addition, the Jains used Prakrit for religious literature, including commentaries on the Jain canonical literature, stories about Jain figures, moral stories, hymns and expositions of Jain doctrine. Prakrit is also the language of some Shaiva tantras and Vaishnava hymns.

Besides being the primary language of several texts, Prakrit also features as the language of low-class men and most women in the Sanskrit stage plays. American scholar Andrew Ollett traces the origin of the Sanskrit Kavya to Prakrit poems.

Some of the texts that identify their language as Prakrit include :

•

Hala's Gaha Sattasai

(c. 1st or 2nd century), anthology of single verse poems

List

of Prakrits :

•

Apabhramsa

Dramatic

Prakrits :

The phrase "Dramatic Prakrits" often refers to three most prominent of them: Shauraseni, Magadhi Prakrit, and Maharashtri Prakrit. However, there were a slew of other less commonly used Prakrits that also fall into this category. These include Prachya, Bahliki, Dakshinatya, Shakari, Chandali, Shabari, Abhiri, Dramili, and Odri. There was a strict structure to the use of these different Prakrits in dramas. Characters each spoke a different Prakrit based on their role and background; for example, Dramili was the language of "forest-dwellers", Sauraseni was spoken by "the heroine and her female friends", and Avanti was spoken by "cheats and rogues".

Status

:

Mirza Khan's Tuhfat al-hind (1676) characterizes Prakrit as the language of "the lowest of the low", stating that the language was known as Patal-bani ("Language of the underground") or Nag-bani ("Language of the snakes").

While Prakrits were originally seen as 'lower' forms of language, the influence they had on Sanskrit - allowing it to be more easily used by the common people - as well as the converse influence of Sanskrit on the Prakrits, gave Prakrits progressively higher cultural cachet. Among modern scholars, Prakrit literature has received less attention than Sanskrit. Few modern Prakrit texts have survived in modern times, and even fewer have been published or attracted critical scholarship. Prakrit has not been designated as a classical language by the Government of India, although the earliest Prakrit texts are older than literature of most of the languages designated as such. One of the reasons behind this neglect of Prakrit is that it is not tied to a regional, national, ethnic, or religious identity.

Research

institutes :

The National Institute of Prakrit Study and Research is located in Shravanabelagola, Karnataka, India.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |