| PROTO - INDO - EUROPEANS The Proto-Indo-Europeans were a hypothetical prehistoric ethnolinguistic group of Eurasia who spoke Proto-Indo-European (PIE), the ancestor of the Indo-European languages according to linguistic reconstruction.

Knowledge of them comes chiefly from that linguistic reconstruction, along with material evidence from archaeology and archaeogenetics. The Proto-Indo-Europeans likely lived during the late Neolithic, or roughly the 4th millennium BC. Mainstream scholarship places them in the Pontic–Caspian steppe zone in Eastern Europe (present day Ukraine and southern Russia). Some archaeologists would extend the time depth of PIE to the middle Neolithic (5500 to 4500 BC) or even the early Neolithic (7500 to 5500 BC), and suggest alternative location hypotheses.

By the early second millennium BC, descendants of the Proto-Indo-Europeans had reached far and wide across Eurasia, including Anatolia (Hittites), the Aegean (the ancestors of Mycenaean Greece), the north of Europe (Corded Ware culture), the edges of Central Asia (Yamnaya culture), and southern Siberia (Afanasievo culture).

Culture

:

•

pastoralism, including domesticated cattle, horses, and dogs

The scholars of the 19th century who first tackled the question of the Indo-Europeans' original homeland (also called Urheimat, from German), had essentially only linguistic evidence. They attempted a rough localization by reconstructing the names of plants and animals (importantly the beech and the salmon) as well as the culture and technology (a Bronze Age culture centered on animal husbandry and having domesticated the horse). The scholarly opinions became basically divided between a European hypothesis, positing migration from Europe to Asia, and an Asian hypothesis, holding that the migration took place in the opposite direction.

In the early 20th century, the question became associated with the expansion of a supposed "Aryan race", a fallacy promoted during the expansion of European empires and the rise of "scientific racism". The question remains contentious within some flavours of ethnic nationalism (see also Indigenous Aryans).

A series of major advances occurred in the 1970s due to the convergence of several factors. First, the radiocarbon dating method (invented in 1949) had become sufficiently inexpensive to be applied on a mass scale. Through dendrochronology (tree-ring dating), pre-historians could calibrate radiocarbon dates to a much higher degree of accuracy. And finally, before the 1970s, parts of Eastern Europe and Central Asia had been off limits to Western scholars, while non-Western archaeologists did not have access to publication in Western peer-reviewed journals. The pioneering work of Marija Gimbutas, assisted by Colin Renfrew, at least partly addressed this problem by organizing expeditions and arranging for more academic collaboration between Western and non-Western scholars.

The Kurgan hypothesis, as of 2017 the most widely held theory, depends on linguistic and archaeological evidence, but is not universally accepted. It suggests PIE origin in the Pontic-Caspian steppe during the Chalcolithic. A minority of scholars prefer the Anatolian hypothesis, suggesting an origin in Anatolia during the Neolithic. Other theories (Armenian hypothesis, Out of India theory, Paleolithic Continuity Theory, Balkan hypothesis) have only marginal scholarly support.

In regard to terminology, in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the term Aryan was used to refer to the Proto-Indo-Europeans and their descendants. However, Aryan more properly applies to the Indo-Iranians, the Indo-European branch that settled parts of the Middle East and South Asia, as only Indic and Iranian languages explicitly affirm the term as a self-designation referring to the entirety of their people, whereas the same Proto-Indo-European root (*aryo-) is the basis for Greek and Germanic word forms which seem only to denote the ruling elite of Proto-Indo-European (PIE) society. In fact, the most accessible evidence available confirms only the existence of a common, but vague, socio-cultural designation of "nobility" associated with PIE society, such that Greek socio-cultural lexicon and Germanic proper names derived from this root remain insufficient to determine whether the concept was limited to the designation of an exclusive, socio-political elite, or whether it could possibly have been applied in the most inclusive sense to an inherent and ancestral "noble" quality which allegedly characterized all ethnic members of PIE society. Only the latter could have served as a true and universal self-designation for the Proto-Indo-European people.

By the early twentieth century this term had come to be widely used in a racist context referring to a hypothesized white, blonde and blue eyed master race, culminating with the pogroms of the Nazis in Europe. Subsequently, the term Aryan as a general term for Indo-Europeans has been largely abandoned by scholars (though the term Indo-Aryan is still used to refer to the branch that settled in Southern Asia).

Urheimat hypotheses :

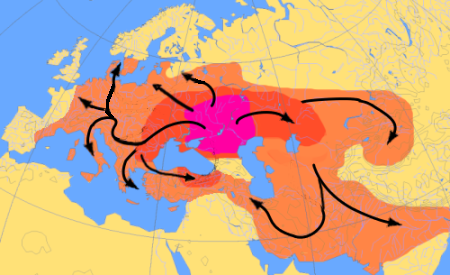

Scheme of Indo-European migrations from ca. 4000 to 1000 BC according

to the Kurgan hypothesis. The magenta area corresponds to the assumed

Urheimat (Samara culture, Sredny Stog culture). The red area corresponds

to the area which may have been settled by Indo-European-speaking

peoples up to ca. 2500 BC; the orange area to 1000 BC.

Researchers have put forward a great variety of proposed locations for the first speakers of Proto-Indo-European. Few of these hypotheses have survived scrutiny by academic specialists in Indo-European studies sufficiently well to be included in modern academic debate.

Pontic-Caspian

steppe hypothesis :

Armenian

highland hypothesis :

Anatolian

hypothesis :

Following the publication of several studies on ancient DNA in 2015, Colin Renfrew has accepted the reality of migrations of populations speaking one or several Indo-European languages from the Pontic steppe towards Northwestern Europe.[need quotation to verify]

Genetics :

This

section possibly contains original research. Please improve it by

verifying the claims made and adding inline citations. Statements

consisting only of original research should be removed. (March 2011)

(Learn how and when to remove this template message)

R1b

and R1a :

R1a

and R1a1a :

A large, 2014 study by Underhill et al., using 16,244 individuals from over 126 populations from across Eurasia, concluded there was compelling evidence, that R1a-M420 originated in the vicinity of Iran. The mutations that characterize haplogroup R1a occurred ~10,000 years BP. Its defining mutation (M17) occurred about 10,000 to 14,000 years ago. Pamjav et al. (2012) believe that R1a originated and initially diversified either within the Eurasian Steppes or the Middle East and Caucasus region.

Ornella Semino et al. propose a postglacial (Holocene) spread of the R1a1 haplogroup from north of the Black Sea during the time of the Late Glacial Maximum, which was subsequently magnified by the expansion of the Kurgan culture into Europe and eastward.

Yamnaya

culture :

The question of where the Yamnaya come from has been something of a mystery up to now we can now answer that, as we've found that their genetic make-up is a mix of Eastern European hunter-gatherers and a population from this pocket of Caucasus hunter-gatherers who weathered much of the last Ice Age in apparent isolation.

An analysis by David W. Anthony (2019) also suggests a genetic origin of proto-Indo-Europeans (the Yamnaya people) in the Eastern European steppe north of the Caucasus, derived from a mixture of Eastern European hunter-gatherers and hunter-gatherers from the Caucasus. Anthony also suggests that the proto-Indo-European language formed mainly from a base of languages spoken by Eastern European hunter-gathers with influences from languages of northern Caucasus hunter-gatherers, in addition to a possible later influence from the language of the Maikop culture to the south (which is hypothesized to have belonged to the North Caucasian family) in the later neolithic or bronze age involving little genetic impact.

Eastern

European hunter-gatherers :

Near

East population :

Jones et al. (2015) analyzed genomes from males from western Georgia, in the Caucasus, from the Late Upper Palaeolithic (13,300 years old) and the Mesolithic (9,700 years old). These two males carried Y-DNA haplogroup: J* and J2a. The researchers found that these Caucasus hunters were probably the source of the farmer-like DNA in the Yamnaya, as the Caucasians were distantly related to the Middle Eastern people who introduced farming in Europe. Their genomes showed that a continued mixture of the Caucasians with Middle Eastern took place up to 25,000 years ago, when the coldest period in the last Ice Age started.

According to Lazaridis et al. (2016), "a population related to the people of the Iran Chalcolithic contributed ~43% of the ancestry of early Bronze Age populations of the steppe." According to Lazaridis et al. (2016), these Iranian Chalcolithic people were a mixture of "the Neolithic people of western Iran, the Levant, and Caucasus Hunter Gatherers." Lazaridis et al. (2016) also note that farming spread at two places in the Near East, namely the Levant and Iran, from where it spread, Iranian people spreading to the steppe and south Asia.

Northern

and Central Europe :

The four Corded Ware people could trace an astonishing three-quarters of their ancestry to the Yamnaya, according to the paper. That suggests a massive migration of Yamnaya people from their steppe homeland into Eastern Europe about 4500 years ago when the Corded Ware culture began, perhaps carrying an early form of Indo-European language.

Bronze

age Greece :

Anatolian

hypothesis :

if the expansions began at 9,500 years ago from Anatolia and at 6,000 years ago from the Yamnaya culture region, then a 3,500-year period elapsed during their migration to the Volga-Don region from Anatolia, probably through the Balkans. There a completely new, mostly pastoral culture developed under the stimulus of an environment unfavourable to standard agriculture, but offering new attractive possibilities. Our hypothesis is, therefore, that Indo-European languages derived from a secondary expansion from the Yamnaya culture region after the Neolithic farmers, possibly coming from Anatolia and settled there, developing pastoral nomadism.

Spencer Wells suggests in a 2001 study that the origin, distribution and age of the R1a1 haplotype points to an ancient migration, possibly corresponding to the spread by the Kurgan people in their expansion across the Eurasian steppe around 3000 BC.

About his old teacher Cavalli-Sforza's proposal, Wells (2002) states that "there is nothing to contradict this model, although the genetic patterns do not provide clear support either", and instead argues that the evidence is much stronger for Gimbutas' model :

While we see substantial genetic and archaeological evidence for an Indo-European migration originating in the southern Russian steppes, there is little evidence for a similarly massive Indo-European migration from the Middle East to Europe. One possibility is that, as a much earlier migration (8,000 years old, as opposed to 4,000), the genetic signals carried by Indo-European-speaking farmers may simply have dispersed over the years. There is clearly some genetic evidence for migration from the Middle East, as Cavalli-Sforza and his colleagues showed, but the signal is not strong enough for us to trace the distribution of Neolithic languages throughout the entirety of Indo-European-speaking Europe.

Iranian/Armenian

hypothesis :

Recent DNA-research has led to renewed suggestions of a Caucasian homeland for the 'proto-Indo-Europeans'. According to Kroonen et al. (2018), Damgaard et al. (2018) ancient Anatolia "show no indication of a large-scale intrusion of a steppe population." They further note that this lends support to the Indo-Hittite hypothesis, according to which both proto-Anatolian and proto-Indo-European split-off from a common mother language "no later than the 4th millennium BCE." Haak et al. (2015) states that "the Armenian plateau hypothesis gains in plausibility" since the Yamnaya partly descended from a Near Eastern population, which resembles present-day Armenians."

Wang et al. (2018) note that the Caucasus served as a corridor for gene flow between the steppe and cultures south of the Caucasus during the Eneolithic and the Bronze Age, stating that this "opens up the possibility of a homeland of PIE south of the Caucasus." However, Wang et al. also comment that the most recent genetic evidence supports an expansion of proto-Indo-Europeans through the steppe, noting: "but the latest ancient DNA results from South Asia also lend weight to a spread of Indo-European languages "via the steppe belt. The spread of some or all of the proto-Indo-European branches would have been possible via the North Caucasus and Pontic region and from there, along with pastoralist expansions, to the heart of Europe. This scenario finds support from the well attested and now widely documented 'steppe ancestry' in European populations, the postulate of increasingly patrilinear societies in the wake of these expansions (exemplified by R1a/R1b), as attested in the latest study on the Bell Beaker phenomenon."

However, David W. Anthony in a 2019 analysis, criticizes the "southern" or "Armenian" hypothesis (addressing Reich, Kristiansen, and Wang). Among his reasons being: that the Yamnaya lack evidence of genetic influence from the bronze age or late neolithic Caucasus (deriving instead from an earlier mixture of Eastern European hunter-gatherers and Caucasus hunter-gatherers) and have paternal lineages that seem to derive from the hunter-gatherers of the Eastern European Steppe rather than the Caucasus, as well as a scarcity in the Yamnaya of the Anatolian Farmer admixture that had become common and substantial in the Caucasus around 5,000 BC. Anthony instead suggests a genetic and linguistic origin of proto-Indo-Europeans (the Yamnaya) in the Eastern European steppe north of the Caucasus, from a mixture of these two groups (EHG and CHG). He suggests that the roots of Proto-Indo-European ("archaic" or proto-proto-Indo-European) were in the steppe rather than the south and that PIE formed mainly from a base of languages spoken by Eastern European hunter-gathers with some influences from languages of Caucasus hunter-gatherers.

Physical

appearance :

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |