| SANSKRUT

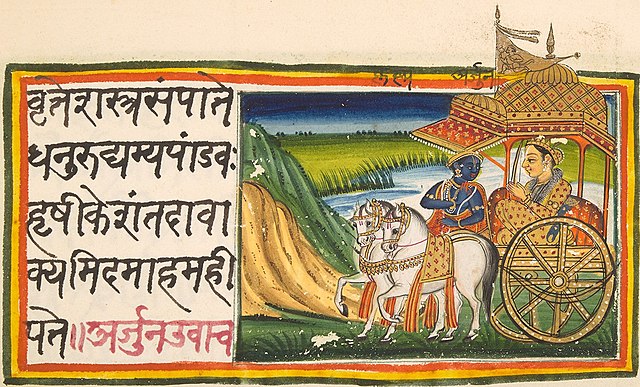

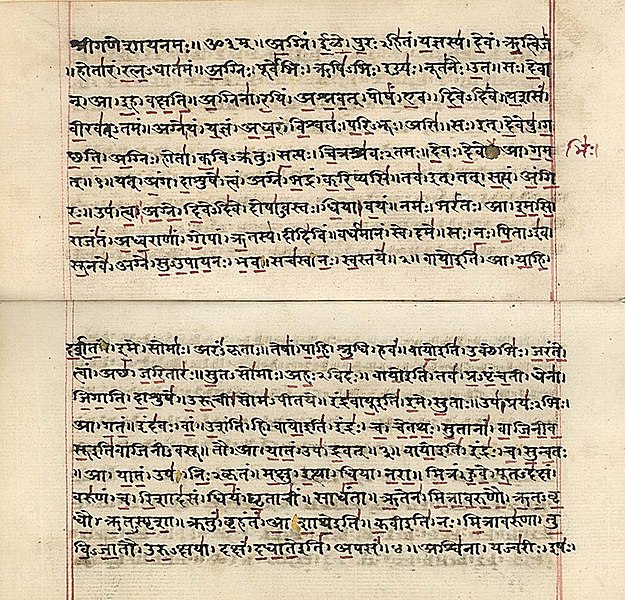

A 19th-century illustrated Sanskrit manuscript from the Bhagwad Gita, composed ca 400 BCE - 200 BCE

The 175th-anniversary stamp of the third-oldest Sanskrit college, Sanskrit College, Calcutta. The oldest is Benares Sanskrit College, founded in 1791

Region : South Asia (ancient and medieval), parts

of Southeast Asia (medieval)

• Indo-Iranian

Early form : Vedic Sanskrit

Sanskrit (Attributively Sanskrut) is a classical language of South Asia belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had diffused there from the northwest in the late Bronze Age. Sanskrit is the sacred language of Hinduism, the language of classical Hindu philosophy, and of historical texts of Buddhism and Jainism. It was a link language in ancient and medieval South Asia, and upon transmission of Hindu and Buddhist culture to Southeast Asia, East Asia and Central Asia in the early medieval era, it became a language of religion and high culture, and of the political elites in some of these regions. As a result, Sanskrit had a lasting impact on the languages of South Asia, Southeast Asia and East Asia, especially in their formal and learned vocabularies.

Sanskrit generally connotes several Old Indo-Aryan varieties. The most archaic of these is Vedic Sanskrit found in the Rig Ved, a collection of 1,028 hymns composed between 1500 BCE and 1200 BCE by Indo-Aryan tribes migrating east from what today is Afghanistan across northern Pakistan and into northern India. Vedic Sanskrit interacted with the preexisting ancient languages of the subcontinent, absorbing names of newly encountered plants and animals; in addition, the ancient Dravidian languages influenced Sanskrit's phonology and syntax. "Sanskrit" can also more narrowly refer to Classical Sanskrit, a refined and standardized grammatical form that emerged in the mid-1st millennium BCE and was codified in the most comprehensive of ancient grammars, the Astadhyayi ("Eight chapters") of Panini. The greatest dramatist in Sanskrit Kalidasa wrote in classical Sanskrit, and the foundations of modern arithmetic were first described in classical Sanskrit. The two major Sanskrit epics, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, however, were composed in a range of oral storytelling registers called Epic Sanskrit which was used in northern India between 400 BCE and 300 CE, and roughly contemporary with classical Sanskrit. In the following centuries Sanskrit became tradition bound, stopped being learned as a first language, and ultimately stopped developing as a living language.

The hymns of the RigVed are notably similar to the most archaic poems of the Iranian and Greek language families, the Gathas of old Avestan and Illiad of Homer. As the RigVed was orally transmitted by methods of memorisation of exceptional complexity, rigour and fidelity, as a single text without variant readings, its preserved archaic syntax and morphology are of vital importance in the reconstruction of the common ancestor language Proto-Indo-European. Sanskrit does not have an attested native script: from around the turn of the 1st-millennium CE, it has been written in various Brahmic scripts, and in the modern era most commonly in Devanagari.

Sanskrit's status, function, and place in India's cultural heritage are recognized by its inclusion in the Constitution of India's Eighth Schedule languages. However, despite attempts at revival, there are no first language speakers of Sanskrit in India. In each of India's recent decadal censuses, several thousand citizens have reported Sanskrit to be their mother tongue, but the numbers are thought to signify a wish to be aligned with the prestige of the language. Sanskrit has been taught in traditional gurukulas since ancient times; it is widely taught today at the secondary school level. The oldest Sanskrit college is the Benares Sanskrit College founded in 1791 during East India Company rule. Sanskrit continues to be widely used as a ceremonial and ritual language in Hindu and Buddhist hymns and chants.

Etymology and nomenclature :

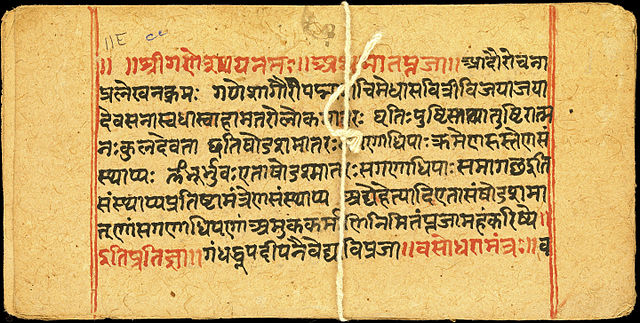

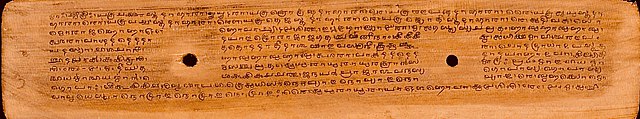

Historic Sanskrit manuscripts: a religious text

A medical text In Sanskrit verbal adjective sámskrta- is a compound word consisting of sam (together, good, well, perfected) and krta- (made, formed, work). It connotes a work that has been "well prepared, pure and perfect, polished, sacred". According to Biderman, the perfection contextually being referred to in the etymological origins of the word is its tonal—rather than semantic—qualities. Sound and oral transmission were highly valued qualities in ancient India, and its sages refined the alphabet, the structure of words and its exacting grammar into a "collection of sounds, a kind of sublime musical mold", states Biderman, as an integral language they called Sanskrit. From the late Vedic period onwards, state Annette Wilke and Oliver Moebus, resonating sound and its musical foundations attracted an "exceptionally large amount of linguistic, philosophical and religious literature" in India. Sound was visualized as "pervading all creation", another representation of the world itself; the "mysterious magnum" of Hindu thought. The search for perfection in thought and the goal of liberation were among the dimensions of sacred sound, and the common thread that weaved all ideas and inspirations became the quest for what the ancient Indians believed to be a perfect language, the "phonocentric episteme" of Sanskrit.

Sanskrit as a language competed with numerous, less exact vernacular Indian languages called Prakritic languages (prakrta-). The term prakrta literally means "original, natural, normal, artless", states Franklin Southworth. The relationship between Prakrit and Sanskrit is found in Indian texts dated to the 1st millennium CE. Patañjali acknowledged that Prakrit is the first language, one instinctively adopted by every child with all its imperfections and later leads to the problems of interpretation and misunderstanding. The purifying structure of the Sanskrit language removes these imperfections. The early Sanskrit grammarian Dandin states, for example, that much in the Prakrit languages is etymologically rooted in Sanskrit, but involve "loss of sounds" and corruptions that result from a "disregard of the grammar". Dandin acknowledged that there are words and confusing structures in Prakrit that thrive independent of Sanskrit. This view is found in the writing of Bharata Muni, the author of the ancient Natyashashtra text. The early Jain scholar Namisadhu acknowledged the difference, but disagreed that the Prakrit language was a corruption of Sanskrit. Namisadhu stated that the Prakrit language was the purvam (came before, origin) and that it came naturally to children, while Sanskrit was a refinement of Prakrit through "purification by grammar".

History :

Origin and development :

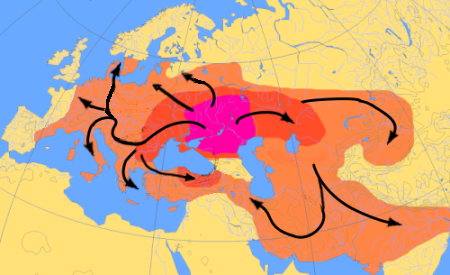

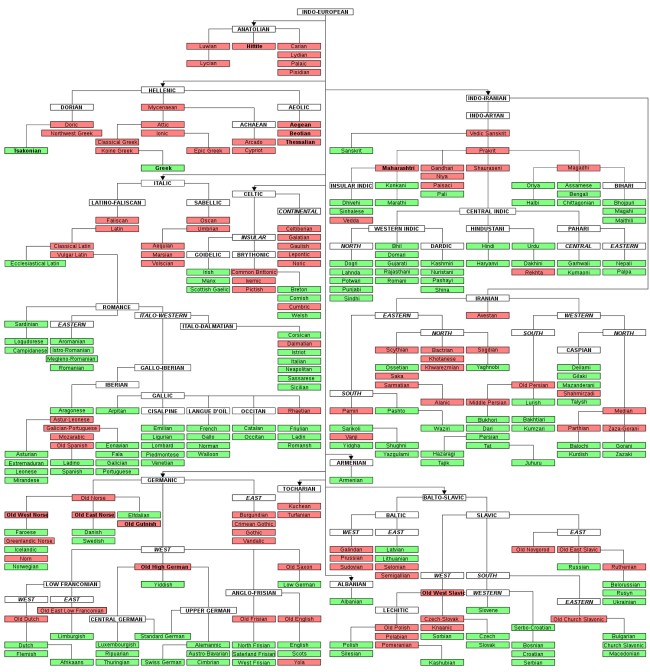

The geographical spread of the Indo-European languages, with Sanskrit in the South Asia Sanskrit belongs to the Indo-European family of languages. It is one of the three earliest ancient documented languages that arose from a common root language now referred to as Proto-Indo-European language :

•

Vedic Sanskrit (c. 1500–500 BCE).

Other Indo-European languages distantly related to Sanskrit include archaic and classical Latin (c. 600 BCE–100 CE, old Italian), Gothic (archaic Germanic language, c. 350 CE), Old Norse (c. 200 CE and after), Old Avestan (c. late 2nd millennium BCE) and Younger Avestan (c. 900 BCE). The closest ancient relatives of Vedic Sanskrit in the Indo-European languages are the Nuristani languages found in the remote Hindu Kush region of the northeastern Afghanistan and northwestern Himalayas, as well as the extinct Avestan and Old Persian — both are Iranian languages. Sanskrit belongs to the satem group of the Indo-European languages.

Colonial era scholars familiar with Latin and Greek were struck by the resemblance of the Sanskrit language, both in its vocabulary and grammar, to the classical languages of Europe. In The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World Mallory and Adams illustrate the resemblance with the following examples :

The correspondences suggest some common root, and historical links between some of the distant major ancient languages of the world.

The Indo-Aryan migrations theory explains the common features shared by Sanskrit and other Indo-European languages by proposing that the original speakers of what became Sanskrit arrived in South Asia from a region of common origin, somewhere north-west of the Indus region, during the early 2nd millennium BCE. Evidence for such a theory includes the close relationship between the Indo-Iranian tongues and the Baltic and Slavic languages, vocabulary exchange with the non-Indo-European Uralic languages, and the nature of the attested Indo-European words for flora and fauna.

The pre-history of Indo-Aryan languages which preceded Vedic Sanskrit is unclear and various hypotheses place it over a fairly wide limit. According to Thomas Burrow, based on the relationship between various Indo-European languages, the origin of all these languages may possibly be in what is now Central or Eastern Europe, while the Indo-Iranian group possibly arose in Central Russia. The Iranian and Indo-Aryan branches separated quite early. It is the Indo-Aryan branch that moved into eastern Iran and then south into South Asia in the first half of the 2nd millennium BCE. Once in ancient India, the Indo-Aryan language underwent rapid linguistic change and morphed into the Vedic Sanskrit language.

Vedic Sanskrit :

The pre-Classical form of Sanskrit is known as Vedic Sanskrit. The earliest attested Sanskrit text is the Rig Ved, a Hindu scripture, from the mid-to-late second millennium BCE. No written records from such an early period survive, if any ever existed, but scholars are confident that the oral transmission of the texts is reliable: They are ceremonial literature, where the exact phonetic expression and its preservation were a part of the historic tradition.

The Rig Ved is a collection of books, created by multiple authors from distant parts of ancient India. These authors represented different generations, and the mandalas 2 to 7 are the oldest while the mandals 1 and 10 are relatively the youngest. Yet, the Vedic Sanskrit in these books of the RigVed "hardly presents any dialectical diversity", states Louis Renou — an Indologist known for his scholarship of the Sanskrit literature and the RigVed in particular. According to Renou, this implies that the Vedic Sanskrit language had a "set linguistic pattern" by the second half of the 2nd millennium BCE. Beyond the RigVed, the ancient literature in Vedic Sanskrit that has survived into the modern age include the SamaVed, YajurVed, AtharvaVed, along with the embedded and layered Vedic texts such as the Brahmanas, Aranyakas, and the early Upanishads. These Vedic documents reflect the dialects of Sanskrit found in the various parts of the northwestern, northern, and eastern Indian subcontinent.(p 9)

Vedic Sanskrit was both a spoken and literary language of ancient India. According to Michael Witzel, Vedic Sanskrit was a spoken language of the semi-nomadic Aryas who temporarily settled in one place, maintained cattle herds, practiced limited agriculture, and after some time moved by wagon trains they called grama. (pp 16–17) The Vedic Sanskrit language or a closely related Indo-European variant was recognized beyond ancient India as evidenced by the "Mitanni Treaty" between the ancient Hittite and Mitanni people, carved into a rock, in a region that are now parts of Syria and Turkey. Parts of this treaty such as the names of the Mitanni princes and technical terms related to horse training, for reasons not understood, are in early forms of Vedic Sanskrit. The treaty also invokes the gods Varuna, Mitra, Indra, and Nasatya found in the earliest layers of the Vedic literature.

The Vedic Sanskrit found in the Rig Ved is distinctly more archaic than other Vedic texts, and in many respects, the Rigvedic language is notably more similar to those found in the archaic texts of Old Avestan Zoroastrian Gathas and Homer's Iliad and Odyssey. According to Stephanie W. Jamison and Joel P. Brereton — Indologists known for their translation of the Rig Ved — the Vedic Sanskrit literature "clearly inherited" from Indo-Iranian and Indo-European times the social structures such as the role of the poet and the priests, the patronage economy, the phrasal equations, and some of the poetic meters. While there are similarities, state Jamison and Brereton, there are also differences between Vedic Sanskrit, the Old Avestan, and the Mycenaean Greek literature. For example, unlike the Sanskrit similes in the Rig Ved, the Old Avestan Gathas lack simile entirely, and it is rare in the later version of the language. The Homerian Greek, like Rigvedic Sanskrit, deploys simile extensively, but they are structurally very different.

Classical Sanskrit :

A 17th-century birch bark manuscript of Panini's grammar treatise from Kashmir The early Vedic form of the Sanskrit language was far less homogenous, and it evolved over time into a more structured and homogeneous language, ultimately into the Classical Sanskrit by about the mid-1st millennium BCE. According to Richard Gombrich—an Indologist and a scholar of Sanskrit, Pali and Buddhist Studies—the archaic Vedic Sanskrit found in the Rig Ved had already evolved in the Vedic period, as evidenced in the later Vedic literature. The language in the early Upanishads of Hinduism and the late Vedic literature approaches Classical Sanskrit, while the archaic Vedic Sanskrit had by the Buddha's time become unintelligible to all except ancient Indian sages, states Gombrich.

The formalization of the Sanskrit language is credited to Panini, along with Patanjali's Mahabhasya and Katyayana's commentary that preceded Patanjali's work. Panini composed Astadhyayi ("Eight-Chapter Grammar"). The century in which he lived is unclear and debated, but his work is generally accepted to be from sometime between 6th and 4th centuries BCE.

The Astadhyayi was not the first description of Sanskrit grammar, but it is the earliest that has survived in full. Panini cites ten scholars on the phonological and grammatical aspects of the Sanskrit language before him, as well as the variants in the usage of Sanskrit in different regions of India. The ten Vedic scholars he quotes are Apisali, Kashyap, Gargya, Galav, Cakravarman, Bharadvaj, Sakatayan, Sakalya, Senak and Sphotayan. The Astadhyayi of Panini became the foundation of Vyakaran, a Vednga. In the Astadhyayi, language is observed in a manner that has no parallel among Greek or Latin grammarians. Panini's grammar, according to Renou and Filliozat, defines the linguistic expression and a classic that set the standard for the Sanskrit language. Panini made use of a technical metalanguage consisting of a syntax, morphology and lexicon. This metalanguage is organised according to a series of meta-rules, some of which are explicitly stated while others can be deduced.

Panini's comprehensive and scientific theory of grammar is conventionally taken to mark the start of Classical Sanskrit. His systematic treatise inspired and made Sanskrit the preeminent Indian language of learning and literature for two millennia. It is unclear whether Panini wrote his treatise on Sanskrit language or he orally created the detailed and sophisticated treatise then transmitted it through his students. Modern scholarship generally accepts that he knew of a form of writing, based on references to words such as lipi ("script") and lipikara ("scribe") in section 3.2 of the Astadhyayi.

The Classical Sanskrit language formalized by Panini, states Renou, is "not an impoverished language", rather it is "a controlled and a restrained language from which archaisms and unnecessary formal alternatives were excluded". The Classical form of the language simplified the sandhi rules but retained various aspects of the Vedic language, while adding rigor and flexibilities, so that it had sufficient means to express thoughts as well as being "capable of responding to the future increasing demands of an infinitely diversified literature", according to Renou. Panini included numerous "optional rules" beyond the Vedic Sanskrit's bahulam framework, to respect liberty and creativity so that individual writers separated by geography or time would have the choice to express facts and their views in their own way, where tradition followed competitive forms of the Sanskrit language.

The phonetic differences between Vedic Sanskrit and Classical Sanskrit are negligible when compared to the intense change that must have occurred in the pre-Vedic period between Indo-Aryan language and the Vedic Sanskrit. The noticeable differences between the Vedic and the Classical Sanskrit include the much-expanded grammar and grammatical categories as well as the differences in the accent, the semantics and the syntax. There are also some differences between how some of the nouns and verbs end, as well as the sandhi rules, both internal and external. Quite many words found in the early Vedic Sanskrit language are never found in late Vedic Sanskrit or Classical Sanskrit literature, while some words have different and new meanings in Classical Sanskrit when contextually compared to the early Vedic Sanskrit literature.

Arthur Macdonell was among the early colonial era scholars who summarized some of the differences between the Vedic and Classical Sanskrit. Louis Renou published in 1956, in French, a more extensive discussion of the similarities, the differences and the evolution of the Vedic Sanskrit within the Vedic period and then to the Classical Sanskrit along with his views on the history. This work has been translated by Jagbans Balbir.

Sanskrit and Prakrit languages :

An early use of the word for "Sanskrit" in Late Brahmi script (also called Gupta script) Mandsaur stone inscription of Yashodharman-Vishnuvardhan, 532 CE The earliest known use of the word Samskrta (Sanskrit), in the context of a speech or language, is found in verses 5.28.17–19 of the Ramayan. Outside the learned sphere of written Classical Sanskrit, vernacular colloquial dialects (Prakrits) continued to evolve. Sanskrit co-existed with numerous other Prakrit languages of ancient India. The Prakrit languages of India also have ancient roots and some Sanskrit scholars have called these Apabhramsa, literally "spoiled". The Vedic literature includes words whose phonetic equivalent are not found in other Indo-European languages but which are found in the regional Prakrit languages, which makes it likely that the interaction, the sharing of words and ideas began early in the Indian history. As the Indian thought diversified and challenged earlier beliefs of Hinduism, particularly in the form of Buddhism and Jainism, the Prakrit languages such as Pali in Theravada Buddhism and Ardhamagadhi in Jainism competed with Sanskrit in the ancient times.However, states Paul Dundas, a scholar of Jainism, these ancient Prakrit languages had "roughly the same relationship to Sanskrit as medieval Italian does to Latin." The Indian tradition states that the Buddha and the Mahavir preferred the Prakrit language so that everyone could understand it. However, scholars such as Dundas have questioned this hypothesis. They state that there is no evidence for this and whatever evidence is available suggests that by the start of the common era, hardly anybody other than learned monks had the capacity to understand the old Prakrit languages such as Ardhamagadhi.

Colonial era scholars questioned whether Sanskrit was ever a spoken language, or just a literary language. Scholars disagree in their answers. A section of Western scholars state that Sanskrit was never a spoken language, while others and particularly most Indian scholars state the opposite. Those who affirm Sanskrit to have been a vernacular language point to the necessity of Sanskrit being a spoken language for the oral tradition that preserved the vast number of Sanskrit manuscripts from ancient India. Secondly, they state that the textual evidence in the works of Yaksa, Panini and Patanajali affirms that the Classical Sanskrit in their era was a language that is spoken (bhasha) by the cultured and educated. Some sutras expound upon the variant forms of spoken Sanskrit versus written Sanskrit. The 7th-century Chinese Buddhist pilgrim Xuanzang mentioned in his memoir that official philosophical debates in India were held in Sanskrit, not in the vernacular language of that region.

Sanskrit's link to the Prakrit languages and other Indo-European languages To view large image click here.

According to Sanskrit linguist Madhav Deshpande, Sanskrit was a spoken language in a colloquial form by the mid-1st millennium BCE which coexisted with a more formal, grammatically correct form of literary Sanskrit. This, states Deshpande, is true for modern languages where colloquial incorrect approximations and dialects of a language are spoken and understood, along with more "refined, sophisticated and grammatically accurate" forms of the same language being found in the literary works. The Indian tradition, states Moriz Winternitz, has favored the learning and the usage of multiple languages from the ancient times. Sanskrit was a spoken language in the educated and the elite classes, but it was also a language that must have been understood in a wider circle of society because the widely popular folk epics and stories such as the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, the Bhagavata Purana, the Panchatantra and many other texts are all in the Sanskrit language. The Classical Sanskrit with its exacting grammar was thus the language of the Indian scholars and the educated classes, while others communicated with approximate or ungrammatical variants of it as well as other natural Indian languages. Sanskrit, as the learned language of Ancient India, thus existed alongside the vernacular Prakrits. Many Sanskrit dramas indicate that the language coexisted with the vernacular Prakrits. Centres in Varanasi, Paithan, Pune and Kanchipuram were centers of classical Sanskrit learning and public debates until the arrival of the colonial era.

According to Étienne Lamotte, an Indologist and Buddhism scholar, Sanskrit became the dominant literary and inscriptional language because of its precision in communication. It was, states Lamotte, an ideal instrument for presenting ideas, and as knowledge in Sanskrit multiplied, so did its spread and influence. Sanskrit was adopted voluntarily as a vehicle of high culture, arts, and profound ideas. Pollock disagrees with Lamotte, but concurs that Sanskrit's influence grew into what he terms a "Sanskrit Cosmopolis" over a region that included all of South Asia and much of southeast Asia. The Sanskrit language cosmopolis thrived beyond India between 300 and 1300 CE.

Dravidian

influence on Sanskrit :

Reinöhl further states that there is a symmetric relationship between Dravidian languages like Kannada or Tamil with Indo-Aryan languages like Bengali or Hindi, whereas the same is not found in Persian or English sentences into non-Indo-Aryan languages. To quote from Reinöhl – "A sentence in a Dravidian language like Tamil or Kannada becomes ordinarily good Bengali or Hindi by substituting Bengali or Hindi equivalents for the Dravidian words and forms, without modifying the word order, but the same thing is not possible in rendering a Persian or English sentence into a non-Indo-Aryan language".

Shulman mentions that "Dravidian nonfinite verbal forms (called vinaiyeccam in Tamil) shaped the usage of the Sanskrit nonfinite verbs (originally derived from inflected forms of action nouns in Vedic). This particularly salient case of possible influence of Dravidian on Sanskrit is only one of many items of syntactic assimilation, not least among them the large repertoire of morphological modality and aspect that, once one knows to look for it, can be found everywhere in classical and postclassical Sanskrit".

Influence :

Sanskrit has been the predominant language of Hindu texts encompassing a rich tradition of philosophical and religious texts, as well as poetry, music, drama, scientific, technical and others. It is the predominant language of one of the largest collection of historic manuscripts. The earliest known inscriptions in Sanskrit are from the 1st century BCE, such as the Ayodhya Inscription of Dhana and Ghosundi-Hathibada (Chittorgarh).

Though developed and nurtured by scholars of orthodox schools of Hinduism, Sanskrit has been the language for some of the key literary works and theology of heterodox schools of Indian philosophies such as Buddhism and Jainism. The structure and capabilities of the Classical Sanskrit language launched ancient Indian speculations about "the nature and function of language", what is the relationship between words and their meanings in the context of a community of speakers, whether this relationship is objective or subjective, discovered or is created, how individuals learn and relate to the world around them through language, and about the limits of language? They speculated on the role of language, the ontological status of painting word-images through sound, and the need for rules so that it can serve as a means for a community of speakers, separated by geography or time, to share and understand profound ideas from each other. These speculations became particularly important to the Mimansa and the Nyaya schools of Hindu philosophy, and later to Vednta and Mahayana Buddhism, states Frits Staal—a scholar of Linguistics with a focus on Indian philosophies and Sanskrit. Though written in a number of different scripts, the dominant language of Hindu texts has been Sanskrit. It or a hybrid form of Sanskrit became the preferred language of Mahayana Buddhism scholarship; for example, one of the early and influential Buddhist philosophers, Nagarjuna (~200 CE), used Classical Sanskrit as the language for his texts. According to Renou, Sanskrit had a limited role in the Theravada tradition (formerly known as the Hinayana) but the Prakrit works that have survived are of doubtful authenticity. Some of the canonical fragments of the early Buddhist traditions, discovered in the 20th century, suggest the early Buddhist traditions used an imperfect and reasonably good Sanskrit, sometimes with a Pali syntax, states Renou. The Mahasamghika and Mahavastu, in their late Hinayana forms, used hybrid Sanskrit for their literature. Sanskrit was also the language of some of the oldest surviving, authoritative and much followed philosophical works of Jainism such as the Tattvartha Sutra by Umaswati. Paul Dundas (2006). Patrick Olivelle (ed.). Between the Empires : Society in India 300 BCE to 400 CE. Oxford University Press. pp. 395–396. ISBN 978-0-19-977507-1.

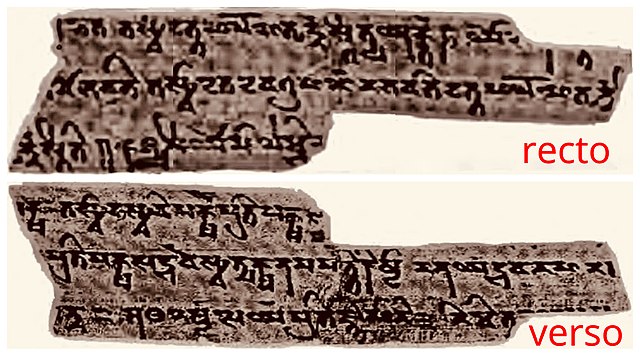

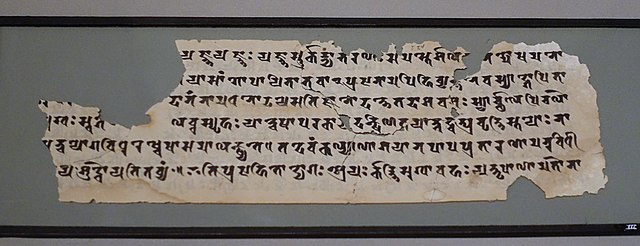

The Spitzer Manuscript is dated to about the 2nd century CE (above:

folio 383 fragment). Discovered near the northern branch of the

Central Asian Silk Route in northwest China, it is the oldest Sanskrit

philosophical manuscript known so far.

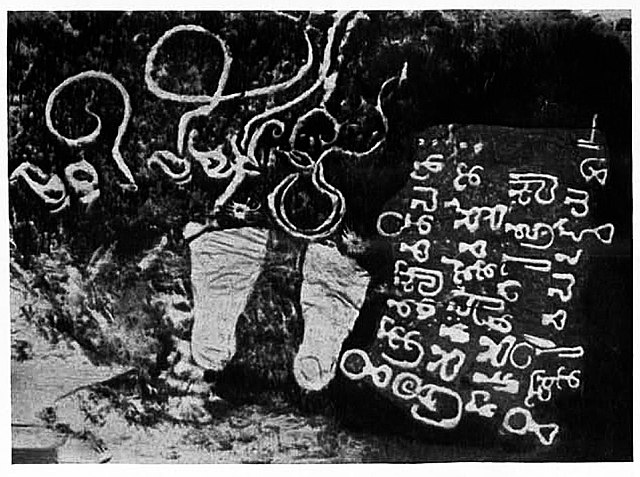

A 5th-century Sanskrit inscription discovered in Java Indonesia—one

of earliest in southeast Asia. The Ciaruteun inscription combines

two writing scripts and compares the king to the Hindu god Vishnu.

It provides a terminus ad quem to the presence of Hinduism in the

Indonesian islands. The oldest southeast Asian Sanskrit inscription—called

the Vo Canh inscription—so far discovered is near Nha Trang,

Vietnam, and it is dated to the late 2nd century to early 3rd century

CE.

Classical Sanskrit is the standard register as laid out in the grammar of Panini, around the fourth century BCE. Its position in the cultures of Greater India is akin to that of Latin and Ancient Greek in Europe. Sanskrit has significantly influenced most modern languages of the Indian subcontinent, particularly the languages of the northern, western, central and eastern Indian subcontinent.

Decline

:

As Hindu kingdoms fell in the eastern and the South India, such as the great Vijayanagar Empire, so did Sanskrit. There were exceptions and short periods of imperial support for Sanskrit, mostly concentrated during the reign of the tolerant Mughal emperor Akbar. Muslim rulers patronized the Middle Eastern language and scripts found in Persia and Arabia, and the Indians linguistically adapted to this Persianization to gain employment with the Muslim rulers. Hindu rulers such as Shivaji of the Maratha Empire, reversed the process, by re-adopting Sanskrit and re-asserting their socio-linguistic identity. After Islamic rule disintegrated in South Asia and the colonial rule era began, Sanskrit re-emerged but in the form of a "ghostly existence" in regions such as Bengal. This decline was the result of "political institutions and civic ethos" that did not support the historic Sanskrit literary culture.

Scholars are divided on whether or when Sanskrit died. Western authors such as John Snelling state that Sanskrit and Pali are both dead Indian languages. Indian authors such as M Ramakrishnan Nair state that Sanskrit was a dead language by the 1st millennium BCE. Sheldon Pollock states that in some crucial way, "Sanskrit is dead". After the 12th century, the Sanskrit literary works were reduced to "reinscription and restatements" of ideas already explored, and any creativity was restricted to hymns and verses. This contrasted with the previous 1,500 years when "great experiments in moral and aesthetic imagination" marked the Indian scholarship using Classical Sanskrit, states Pollock.

Other scholars state that the Sanskrit language did not die, only declined. Hanneder disagrees with Pollock, finding his arguments elegant but "often arbitrary". According to Hanneder, a decline or regional absence of creative and innovative literature constitutes a negative evidence to Pollock's hypothesis, but it is not positive evidence. A closer look at Sanskrit in the Indian history after the 12th century suggests that Sanskrit survived despite the odds.

According to Hanneder, on a more public level the statement that Sanskrit is a dead language is misleading, for Sanskrit is quite obviously not as dead as other dead languages and the fact that it is spoken, written and read will probably convince most people that it cannot be a dead language in the most common usage of the term. Pollock's notion of the "death of Sanskrit" remains in this unclear realm between academia and public opinion when he says that "most observers would agree that, in some crucial way, Sanskrit is dead."

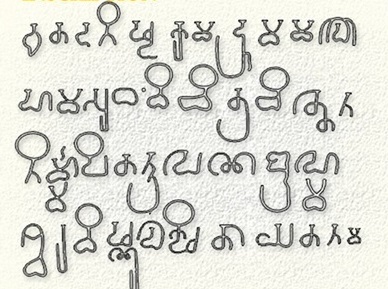

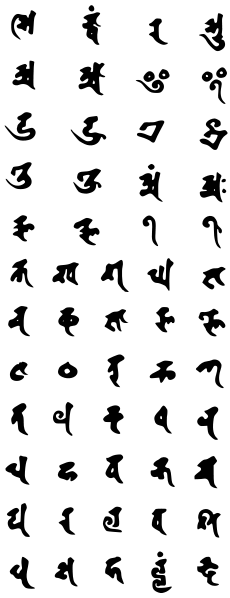

Sanskrit language manuscripts exist in many scripts :

Isha Upanishad (Devanagari)

Sam Ved (Tamil Granth)

Bhagavad Gita (Gurmukhi)

Vedant Sar (Telugu)

Jatakamala (early Sharad) (Buddhist text) The Sanskrit language scholar Moriz Winternitz states, Sanskrit was never a dead language and it is still alive though its prevalence is lesser than ancient and medieval times. Sanskrit remains an integral part of Hindu journals, festivals, Ramlila plays, drama, rituals and the rites-of-passage. Similarly, Brian Hatcher states that the "metaphors of historical rupture" by Pollock are not valid, that there is ample proof that Sanskrit was very much alive in the narrow confines of surviving Hindu kingdoms between the 13th and 18th centuries, and its reverence and tradition continues.

Hanneder states that modern works in Sanskrit are either ignored or their "modernity" contested.

According to Robert Goldman and Sally Sutherland, Sanskrit is neither "dead" nor "living" in the conventional sense. It is a special, timeless language that lives in the numerous manuscripts, daily chants and ceremonial recitations, a heritage language that Indians contextually prize and some practice.

When the British introduced English to India in the 19th century, knowledge of Sanskrit and ancient literature continued to flourish as the study of Sanskrit changed from a more traditional style into a form of analytical and comparative scholarship mirroring that of Europe.

Modern

Indo-Aryan languages :

Vedic Sanskrit belongs to the early Old Indo-Aryan while Classical Sanskrit to the later Old Indo-Aryan stage. The evidence for Prakrits such as Pali (Theravad Buddhism) and Ardhamagadhi (Jainism), along with Magadhi, Maharashtri, Sinhala, Sauraseni and Niya (Gandhari), emerge in the Middle Indo-Aryan stage in two versions—archaic and more formalized—that may be placed in early and middle substages of the 600 BCE – 1000 CE period. Two literary Indo-Aryan languages can be traced to the late Middle Indo-Aryan stage and these are Apabhramsa and Elu (a form of literary Sinhalese). Numerous North, Central, Eastern and Western Indian languages, such as Hindi, Gujarati, Sindhi, Punjabi, Kashmiri, Nepali, Braj, Awadhi, Bengali, Assamese, Oriya, Marathi, and others belong to the New Indo-Aryan stage.

There is an extensive overlap in the vocabulary, phonetics and other aspects of these New Indo-Aryan languages with Sanskrit, but it is neither universal nor identical across the languages. They likely emerged from a synthesis of the ancient Sanskrit language traditions and an admixture of various regional dialects. Each language has some unique and regionally creative aspects, with unclear origins. Prakrit languages do have a grammatical structure, but like the Vedic Sanskrit, it is far less rigorous than Classical Sanskrit. The roots of all Prakrit languages may be in the Vedic Sanskrit and ultimately the Indo-Aryan language, their structural details vary from the Classical Sanskrit. It is generally accepted by scholars and widely believed in India that the modern Indo-Aryan languages, such as Bengali, Gujarati, Hindi and Punjabi are descendants of the Sanskrit language. Sanskrit, states Burjor Avari, can be described as "the mother language of almost all the languages of north India".

Geographic distribution :

Sanskrit language's historical presence has been attested in many

countries. The evidence includes manuscript pages and inscriptions

discovered in South Asia, Southeast Asia and Central Asia. These

have been dated between 300 and 1800 CE.

South Asia has been the geographic range of the largest collection of the ancient and pre-18th-century Sanskrit manuscripts and inscriptions. Beyond ancient India, significant collections of Sanskrit manuscripts and inscriptions have been found in China (particularly the Tibetan monasteries), Myanmar, Indonesia, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, Thailand, and Malaysia. Sanskrit inscriptions, manuscripts or its remnants, including some of the oldest known Sanskrit written texts, have been discovered in dry high deserts and mountainous terrains such as in Nepal, Tibet, Afghanistan, Mongolia, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Kazakhstan. Some Sanskrit texts and inscriptions have also been discovered in Korea and Japan.

Official

status :

Phonology

:

The most significant and distinctive phonological development in Sanskrit is vowel-merger, states Stephanie Jamison—an Indo-European linguist specializing in Sanskrit literature. The short *e, *o and *a, all merge as a in Sanskrit, while long *e, *o and *a, all merge as long a. These mergers occurred very early and significantly impacted Sanskrit's morphological system. Some phonological developments in it mirror those in other PIE languages. For example, the labiovelars merged with the plain velars as in other satem languages. The secondary palatalization of the resulting segments is more thorough and systematic within Sanskrit, states Jamison. A series of retroflex dental stops were innovated in Sanskrit to more thoroughly articulate sounds for clarity. For example, unlike the loss of the morphological clarity from vowel contraction that is found in early Greek and related southeast European languages, Sanskrit deployed *y, *w, and *s intervocalically to provide morphological clarity.

Vowels

:

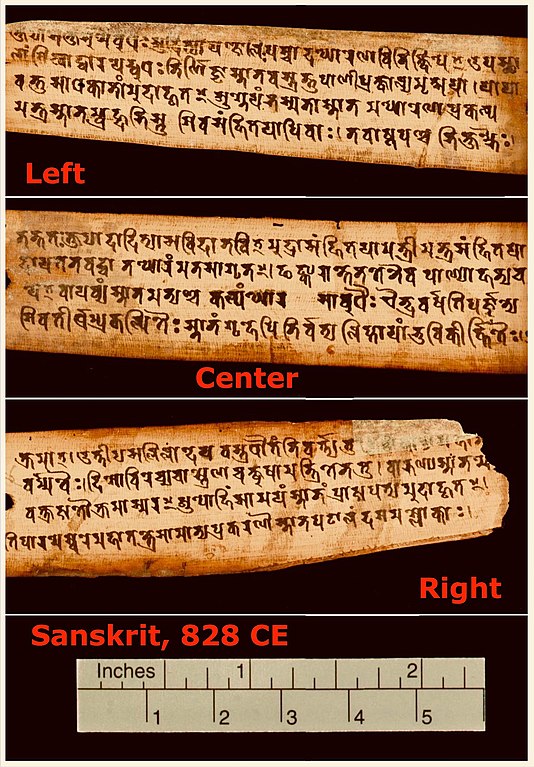

This is one of the oldest surviving and dated palm-leaf manuscript in Sanskrit (828 CE). Discovered in Nepal, the bottom leaf shows all the vowels and consonants of Sanskrit (the first five consonants are highlighted in blue and yellow).

According to Masica, Sanskrit has four traditional semivowels, with which were classed, "for morphophonemic reasons, the liquids: y, r, l, and v; that is, as y and v were the non-syllabics corresponding to i, u, so were r, l in relation to r and l". The northwestern, the central and the eastern Sanskrit dialects have had a historic confusion between "r" and "l". The Paninian system that followed the central dialect preserved the distinction, likely out of reverence for the Vedic Sanskrit that distinguished the "r" and "l". However, the northwestern dialect only had "r", while the eastern dialect probably only had "l", states Masica. Thus literary works from different parts of ancient India appear inconsistent in their use of "r" and "l", resulting in doublets that is occasionally semantically differentiated.

Consonants

:

Sanskrit had a series of retroflex stops. All the retroflexes in Sanskrit are in "origin conditioned alternants of dentals, though from the beginning of the language they have a qualified independence", states Jamison.

Regarding the palatal plosives, the pronunciation is a matter of debate. In contemporary attestation, the palatal plosives are a regular series of palatal stops, supported by most Sanskrit sandhi rules. However, the reflexes in descendant languages, as well as a few of the sandhi rules regarding ch, could suggest an affricate pronunciation.

jh was a marginal phoneme in Sanskrit, hence its phonology is more difficult to reconstruct; it was more commonly employed in the Middle Indo-Aryan languages as a result of phonological processes resulting in the phoneme.

The palatal nasal is a conditioned variant of n occurring next to palatal obstruents. The anusvara that Sanskrit deploys is a conditioned alternant of postvocalic nasals, under certain sandhi conditions. Its visarga is a word-final or morpheme-final conditioned alternant of s and r under certain sandhi conditions.

The voiceless aspirated series is also an innovation in Sanskrit but is significantly rarer than the other three series.

While the Sanskrit language organizes sounds for expression beyond those found in the PIE language, it retained many features found in the Iranian and Balto-Slavic languages. An example of a similar process in all three, states Jamison, is the retroflex sibilant ? being the automatic product of dental s following i, u, r, and k (mnemonically "ruki").

Phonological

alternations, sandhi rules :

The internal sandhi rules are more intricate and account for the root and the canonical structure of the Sanskrit word. These rules anticipate what are now known as the Bartholomae's law and Grassmann's law. For example, states Jamison, the "voiceless, voiced, and voiced aspirated obstruents of a positional series regularly alternate with each other (p ˜ b ˜ b; t ˜ d ˜ d, etc.; note, however, c ˜ j ˜ h), such that, for example, a morpheme with an underlying voiced aspirate final may show alternants [clarification needed] with all three stops under differing internal sandhi conditions". The velar series (k, g, gh) alternate with the palatal series (c, j, h), while the structural position of the palatal series is modified into a retroflex cluster when followed by dental. This rule create two morphophonemically distinct series from a single palatal series.

Vocalic alternations in the Sanskrit morphological system is termed "strengthening", and called guna and vriddhi in the preconsonantal versions. There is an equivalence to terms deployed in Indo-European descriptive grammars, wherein Sanskrit's unstrengthened state is same as the zero-grade, guna corresponds to normal-grade, while vriddhi is same as the lengthened-state. The qualitative ablaut is not found in Sanskrit just like it is absent in Iranian, but Sanskrit retains quantitative ablaut through vowel strengthening. The transformations between unstrengthened to guna is prominent in the morphological system, states Jamison, while vriddhi is a particularly significant rule when adjectives of origin and appurtenance are derived. The manner in which this is done slightly differs between the Vedic and the Classical Sanskrit.

Sanskrit grants a very flexible syllable structure, where they may begin or end with vowels, be single consonants or clusters. Similarly, the syllable may have an internal vowel of any weight. The Vedic Sanskrit shows traces of following the Sievers-Edgerton Law, but Classical Sanskrit doesn't. Vedic Sanskrit has a pitch accent system, states Jamison, which were acknowledged by Panini, but in his Classical Sanskrit the accents disappear.Most Vedic Sanskrit words have one accent. However, this accent is not phonologically predictable, states Jamison. It can fall anywhere in the word and its position often conveys morphological and syntactic information.According to Masica, the presence of an accent system in Vedic Sanskrit is evidenced from the markings in the Vedic texts. This is important because of Sanskrit's connection to the PIE languages and comparative Indo-European linguistics.

Sanskrit, like most early Indo-European languages, lost the so-called "laryngeal consonants (cover-symbol *H) present in the Proto-Indo-European", states Jamison. This significantly impacted the evolutionary path of the Sanskrit phonology and morphology, particularly in the variant forms of roots.

Pronunciation

:

Morphology

:

A Sanskrit word has the following canonical structure :

Root

+ Affix0-n + Ending0–1

A verb in Sanskrit has the following canonical structure :

Root

+ Suffix Tense-Aspect + Suffix Mood + Ending Personal-Number-Voice

Both verbs and nouns in Sanskrit are either thematic or athematic, states Jamison. Guna (strengthened) forms in the active singular regularly alternate in athematic verbs. The finite verbs of Classical Sanskrit have the following grammatical categories: person, number, voice, tense-aspect, and mood. According to Jamison, a portmanteau morpheme generally expresses the person-number-voice in Sanskrit, and sometimes also the ending or only the ending. The mood of the word is embedded in the affix.

These elements of word architecture are the typical building blocks in Classical Sanskrit, but in Vedic Sanskrit these elements fluctuate and are unclear. For example, in the RigVed preverbs regularly occur in tmesis, states Jamison, which means they are "separated from the finite verb". This indecisiveness is likely linked to Vedic Sanskrit's attempt to incorporate accent. With nonfinite forms of the verb and with nominal derivatives thereof, states Jamison, "preverbs show much clearer univerbation in Vedic, both by position and by accent, and by Classical Sanskrit, tmesis is no longer possible even with finite forms".

While roots are typical in Sanskrit, some words do not follow the canonical structure. A few forms lack both inflection and root. Many words are inflected (and can enter into derivation) but lack a recognizable root. Examples from the basic vocabulary include kinship terms such as matar- (mother), nas- (nose), svan- (dog). According to Jamison, pronouns and some words outside the semantic categories also lack roots, as do the numerals. Similarly, the Sanskrit language is flexible enough to not mandate inflection.

The Sanskrit words can contain more than one affix that interact with each other. Affixes in Sanskrit can be athematic as well as thematic, according to Jamison. Athematic affixes can be alternating. Sanskrit deploys eight cases, namely nominative, accusative, instrumental, dative, ablative, genitive, locative, vocative.

Stems, that is "root + affix", appear in two categories in Sanskrit: vowel stems and consonant stems. Unlike some Indo-European languages such as Latin or Greek, according to Jamison, "Sanskrit has no closed set of conventionally denoted noun declensions". Sanskrit includes a fairly large set of stem-types. The linguistic interaction of the roots, the phonological segments, lexical items and the grammar for the Classical Sanskrit consist of four Paninian components. These, states Paul Kiparsky, are the Astadhyaayi, a comprehensive system of 4,000 grammatical rules, of which a small set are frequently used; Sivasutras, an inventory of anubandhas (markers) that partition phonological segments for efficient abbreviations through the pratyharas technique; Dhatupatha, a list of 2,000 verbal roots classified by their morphology and syntactic properties using diacritic markers, a structure that guides its writing systems; and, the Ganapatha, an inventory of word groups, classes of lexical systems. There are peripheral adjuncts to these four, such as the Unadisutras, which focus on irregularly formed derivatives from the roots.

Sanskrit morphology is generally studied in two broad fundamental categories: the nominal forms and the verbal forms. These differ in the types of endings and what these endings mark in the grammatical context. Pronouns and nouns share the same grammatical categories, though they may differ in inflection. Verb-based adjectives and participles are not formally distinct from nouns. Adverbs are typically frozen case forms of adjectives, states Jamison, and "nonfinite verbal forms such as infinitives and gerunds also clearly show frozen nominal case endings".

Tense

and voice :

The paradigm for the tense-aspect system in Sanskrit is the three-way contrast between the "present", the "aorist" and the "perfect" architecture. Vedic Sanskrit is more elaborate and had several additional tenses. For example, the RigVed includes perfect and a marginal pluperfect. Classical Sanskrit simplifies the "present" system down to two tenses, the perfect and the imperfect, while the "aorist" stems retain the aorist tense and the "perfect" stems retain the perfect and marginal pluperfect. The classical version of the language has elaborate rules for both voice and the tense-aspect system to emphasize clarity, and this is more elaborate than in other Indo-European languages. The evolution of these systems can be seen from the earliest layers of the Vedic literature to the late Vedic literature.

Gender,

mood :

There are three persons in Sanskrit: first, second and third. Sanskrit uses the 3×3 grid formed by the three numbers and the three persons parameters as the paradigm and the basic building block of its verbal system.

The Sanskrit language incorporates three genders: feminine, masculine and neuter. All nouns have inherent gender, but with some exceptions, personal pronouns have no gender. Exceptions include demonstrative and anaphoric pronouns. Derivation of a word is used to express the feminine. Two most common derivations come from feminine-forming suffixes, the -a- (AA, Radha) and -i- (EE, Rukmini). The masculine and neuter are much simpler, and the difference between them is primarily inflectional. Similar affixes for the feminine are found in many Indo-European languages, states Burrow, suggesting links of the Sanskrit to its PIE heritage.

Pronouns in Sanskrit include the personal pronouns of the first and second persons, unmarked for gender, and a larger number of gender-distinguishing pronouns and adjectives. Examples of the former include ahám (first singular), vayám (first plural) and yuyám (second plural). The latter can be demonstrative, deictic or anaphoric. Both the Vedic and Classical Sanskrit share the sá/tám pronominal stem, and this is the closest element to a third person pronoun and an article in the Sanskrit language, states Jamison.

Indicative, potential and imperative are the three mood forms in Sanskrit.

Prosody,

meter :

Sanskrit prosody includes linear and non-linear systems. The system started off with seven major metres, according to Annette Wilke and Oliver Moebus, called the "seven birds" or "seven mouths of Brihaspati", and each had its own rhythm, movements and aesthetics wherein a non-linear structure (aperiodicity) was mapped into a four verse polymorphic linear sequence. A syllable in Sanskrit is classified as either laghu (light) or guru (heavy). This classification is based on a matra (literally, "count, measure, duration"), and typically a syllable that ends in a short vowel is a light syllable, while those that end in consonant, anusvara or visarga are heavy. The classical Sanskrit found in Hindu scriptures such as the Bhagavad Gita and many texts are so arranged that the light and heavy syllables in them follow a rhythm, though not necessarily a rhyme.

Sanskrit metres include those based on a fixed number of syllables per verse, and those based on fixed number of morae per verse. The Vedic Sanskrit employs fifteen metres, of which seven are common, and the most frequent are three (8-, 11- and 12-syllable lines). The Classical Sanskrit deploys both linear and non-linear metres, many of which are based on syllables and others based on diligently crafted verses based on repeating numbers of morae (matra per foot).

Meter and rhythm is an important part of the Sanskrit language. It may have played a role in helping preserve the integrity of the message and Sanskrit texts. The verse perfection in the Vedic texts such as the verse Upanishads[t] and post-Vedic Smriti texts are rich in prosody. This feature of the Sanskrit language led some Indologists from the 19th century onwards to identify suspected portions of texts where a line or sections are off the expected metre.

The meter-feature of the Sanskrit language embeds another layer of communication to the listener or reader. A change in metres has been a tool of literary architecture and an embedded code to inform the reciter and audience that it marks the end of a section or chapter. Each section or chapter of these texts uses identical metres, rhythmically presenting their ideas and making it easier to remember, recall and check for accuracy. Authors coded a hymn's end by frequently using a verse of a metre different than that used in the hymn's body. However, Hindu tradition does not use the Gayatri metre to end a hymn or composition, possibly because it has enjoyed a special level of reverence in Hinduism.

Writing system :

One of the oldest surviving Sanskrit manuscript pages in Gupta script (~828 CE), discovered in Nepal The early history of writing Sanskrit and other languages in ancient India is a problematic topic despite a century of scholarship, states Richard Salomon—an epigraphist and Indologist specializing in Sanskrit and Pali literature. The earliest possible script from South Asia is from the Indus Valley Civilization (3rd/2nd millennium BCE), but this script – if it is a script – remains undeciphered. If any scripts existed in the Vedic period, they have not survived. Scholars generally accept that Sanskrit was spoken in an oral society, and that an oral tradition preserved the extensive Vedic and Classical Sanskrit literature. Other scholars such as Jack Goody state that the Vedic Sanskrit texts are not the product of an oral society, basing this view by comparing inconsistencies in the transmitted versions of literature from various oral societies such as the Greek, Serbian, and other cultures, then noting that the Vedic literature is too consistent and vast to have been composed and transmitted orally across generations, without being written down.

Lipi is the term in Sanskrit which means "writing, letters, alphabet". It contextually refers to scripts, the art or any manner of writing or drawing. The term, in the sense of a writing system, appears in some of the earliest Buddhist, Hindu, and Jaina texts. Panini's Astadhyayi, composed sometime around the 5th or 4th century BCE, for example, mentions lipi in the context of a writing script and education system in his times, but he does not name the script. Several early Buddhist and Jaina texts, such as the Lalitavistara Sutra and Pannavana Sutta include lists of numerous writing scripts in ancient India. The Buddhist texts list the sixty four lipi that the Buddha knew as a child, with the Brahmi script topping the list. "The historical value of this list is however limited by several factors", states Salomon. The list may be a later interpolation. The Jain canonical texts such as the Pannavana Sutta—probably older than the Buddhist texts—list eighteen writing systems, with the Brahmi topping the list and Kharotthi (Kharoshthi) listed as fourth. The Jaina text elsewhere states that the "Brahmi is written in 18 different forms", but the details are lacking. However, the reliability of these lists has been questioned and the empirical evidence of writing systems in the form of Sanskrit or Prakrit inscriptions dated prior to the 3rd century BCE has not been found. If the ancient surface for writing Sanskrit was palm leaves, tree bark and cloth—the same as those in later times, these have not survived. According to Salomon, many find it difficult to explain the "evidently high level of political organization and cultural complexity" of ancient India without a writing system for Sanskrit and other languages.

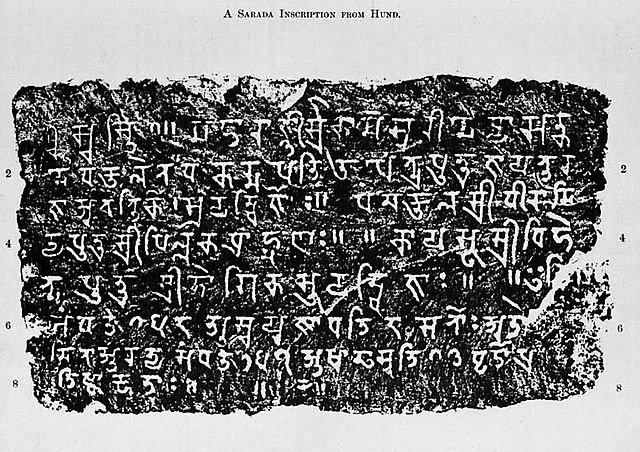

The oldest datable writing systems for Sanskrit are the Brahmi script, the related Kharosthi script and the Brahmi derivatives. The Kharosthi was used in the northwestern part of South Asia and it became extinct, while the Brahmi was used in all over the subcontinent along with regional scripts such as Old Tamil. Of these, the earliest records in the Sanskrit language are in Brahmi, a script that later evolved into numerous related Indic scripts for Sanskrit, along with Southeast Asian scripts (Burmese, Thai, Lao, Khmer, others) and many extinct Central Asian scripts such as those discovered along with the Kharosthi in the Tarim Basin of western China and in Uzbekistan. The most extensive inscriptions that have survived into the modern era are the rock edicts and pillar inscriptions of the 3rd-century BCE Mauryan emperor Ashok, but these are not in Sanskrit.

Scripts

:

Brahmi script :

One of the oldest Hindu Sanskrit inscriptions, the broken pieces

of this early-1st-century BCE Hathibada Brahmi Inscription were

discovered in Rajasthan. It is a dedication to deities Vasudeva-Samkarshana

(Krishna-Balarama) and mentions a stone temple.

The Brahmi script evolved into "a vast number of forms and derivatives", states Richard Salomon, and in theory, Sanskrit "can be represented in virtually any of the main Brahmi-based scripts and in practice it often is".Sanskrit does not have a native script. Being a phonetic language, it can be written in any precise script that efficiently maps unique human sounds to unique symbols. [clarification needed] From the ancient times, it has been written in numerous regional scripts in South and Southeast Asia. Most of these are descendants of the Brahmi script. The earliest datable varnamala Brahmi alphabet system, found in later Sanskrit texts, is from the 2nd century BCE, in the form of a terracotta plaque found in Sughana, Haryana. It shows a "schoolboy's writing lessons", states Salomon.

Nagari

script :

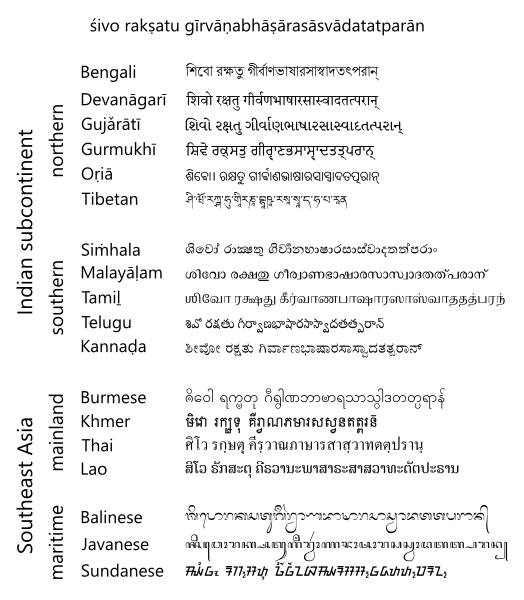

Sanskrit in modern Indian and other Brahmi scripts: May Sihv bless those who take delight in the language of the gods. (Kalidas) The Nagari script has been thought as a north Indian script for Sanskrit as well as the regional languages such as Hindi, Marathi and Nepali. However, it has had a "supra-local" status as evidenced by 1st-millennium CE epigraphy and manuscripts discovered all over India and as far as Sri Lanka, Burma, Indonesia and in its parent form called the Siddhamatrka script found in manuscripts of East Asia. The Sanskrit and Balinese languages Sanur inscription on Belanjong pillar of Bali (Indonesia), dated to about 914 CE, is in part in the Nagari script.

The Nagari script used for Classical Sanskrit has the fullest repertoire of characters consisting of fourteen vowels and thirty three consonants. For the Vedic Sanskrit, it has two more allophonic consonantal characters. To communicate phonetic accuracy, it also includes several modifiers such as the anusvara dot and the visarga double dot, punctuation symbols and others such as the halanta sign.

Other

writing systems :

One of the earliest known Sanskrit inscriptions in Tamil Grantha script at a rock-cut Hindu Trimurti temple (Mandakapattu, c. 615 CE) In the south, where Dravidian languages predominate, scripts used for Sanskrit include the Kannada, Telugu, Malayalam and Grantha alphabets.

Transliteration

schemes, Romanisation :

European scholars in the 19th century generally preferred Devanagari for the transcription and reproduction of whole texts and lengthy excerpts. However, references to individual words and names in texts composed in European Languages were usually represented with Roman transliteration. From the 20th century onwards, because of production costs, textual editions edited by Western scholars have mostly been in Romanised transliteration.

Epigraphy

:

Besides these few examples from the 1st century BCE, the earliest Sanskrit and hybrid dialect inscriptions are found in Mathura (Uttar Pradesh). These date to the 1st and 2nd century CE, states Salomon, from the time of the Indo-Scythian Northern Satraps and the subsequent Kushan Empire. These are also in the Brahmi script. The earliest of these, states Salomon, are attributed to Ksatrapa Sodasa from the early years of 1st century CE. Of the Mathura inscriptions, the most significant is the Mora Well Inscription. In a manner similar to the Hathibada inscription, the Mora well inscription is a dedicatory inscription and is linked to the cult of the Vrishni heroes: it mentions a stone shrine (temple), pratima (murti, images) and calls the five Vrishnis as bhagavatam. There are many other Mathura Sanskrit inscriptions in Brahmi script overlapping the era of Indo-Scythian Northern Satraps and early Kushanas. Other significant 1st-century inscriptions in reasonably good classical Sanskrit in the Brahmi script include the Vasu Doorjamb Inscription and the Mountain Temple inscription. The early ones are related to the Brahmanical, except for the inscription from Kankali Tila which may be Jaina, but none are Buddhist. A few of the later inscriptions from the 2nd century CE include Buddhist Sanskrit, while others are in "more or less" standard Sanskrit and related to the Brahmanical tradition.

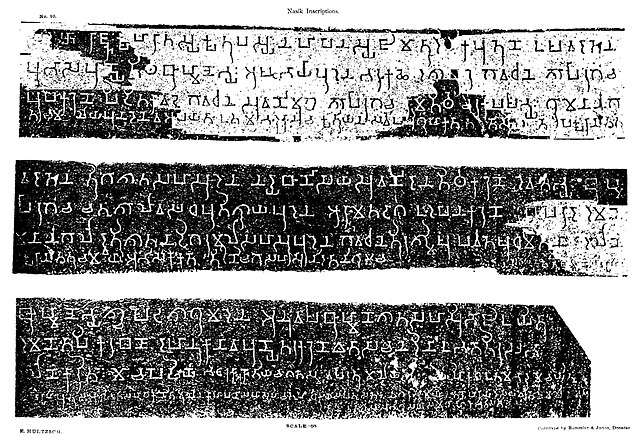

Starting in about the 1st century BCE, Sanskrit has been written in many South Asian, Southeast Asian and Central Asian scripts In Maharashtra and Gujarat, Brahmi script Sanskrit inscriptions from the early centuries of the common era exist at the Nasik Caves site, near the Girnar mountain of Junagadh and elsewhere such as at Kanakhera, Kanheri, and Gunda. The Nasik inscription dates to the mid-1st century CE, is a fair approximation of standard Sanskrit and has hybrid features. The Junagadh rock inscription of Western Satraps ruler Rudradaman I (c. 150 CE, Gujarat) is the first long poetic-style inscription in "more or less" standard Sanskrit that has survived into the modern era. It represents a turning point in the history of Sanskrit epigraphy, states Salomon. Though no similar inscriptions are found for about two hundred years after the Rudradaman reign, it is important because its style is the prototype of the eulogy-style Sanskrit inscriptions found in the Gupta Empire era. These inscriptions are also in the Brahmi script.

The Nagarjunakonda inscriptions are the earliest known substantial South Indian Sanskrit inscriptions, probably from the late 3rd century or early 4th century CE, or both. These inscriptions are related to Buddhism and the Shaivism tradition of Hinduism. A few of these inscriptions from both traditions are verse-style in the classical Sanskrit language, while some such as the pillar inscription is written in prose and a hybridized Sanskrit language. An earlier hybrid Sanskrit inscription found on Amaravati slab is dated to the late 2nd century, while a few later ones include Sanskrit inscriptions along with Prakrit inscriptions related to Hinduism and Buddhism. After the 3rd century CE, Sanskrit inscriptions dominate and many have survived. Between the 4th and 7th centuries CE, south Indian inscriptions are exclusively in the Sanskrit language. In the eastern regions of South Asia, scholars report minor Sanskrit inscriptions from the 2nd century, these being fragments and scattered. The earliest substantial true Sanskrit language inscription of Susuniya (West Bengal) is dated to the 4th century. Elsewhere, such as Dehradun (Uttarakhand), inscriptions in more or less correct classical Sanskrit inscriptions are dated to the 3rd century.

According to Salomon, the 4th-century reign of Samudragupta was the turning point when the classical Sanskrit language became established as the "epigraphic language par excellence" of the Indian world. These Sanskrit language inscriptions are either "donative" or "panegyric" records. Generally in accurate classical Sanskrit, they deploy a wide range of regional Indic writing systems extant at the time. They record the donation of a temple or stupa, images, land, monasteries, pilgrim's travel record, public infrastructure such as water reservoir and irrigation measures to prevent famine. Others praise the king or the donor in lofty poetic terms. The Sanskrit language of these inscriptions is written on stone, various metals, terracotta, wood, crystal, ivory, shell, and cloth.

The evidence of the use of the Sanskrit language in Indic writing systems appears in southeast Asia in the first half of the 1st millennium CE. A few of these in Vietnam are bilingual where both the Sanskrit and the local language is written in the Indian alphabet. Early Sanskrit language inscriptions in Indic writing systems are dated to the 4th century in Malaysia, 5th to 6th centuries in Thailand near Si Thep and the Sak River, early 5th century in Kutai (east Borneo) and mid-5th century in west Java (Indonesia). Both major writing systems for Sanskrit, the North Indian and South Indian scripts, have been discovered in southeast Asia, but the Southern variety with its rounded shapes are far more common. The Indic scripts, particularly the Pallava script prototype, spread and ultimately evolved into Mon-Burmese, Khmer, Thai, Laos, Sumatran, Celebes, Javanese and Balinese scripts. From about the 5th century, Sanskrit inscriptions become common in many parts of South Asia and Southeast Asia, with significant discoveries in Nepal, Vietnam and Cambodia.

Texts

: Sanskrit literature by tradition

Influence

on other languages :

Indic languages

Sanskrit has had a historical presence and influence in many parts

of Asia. Above (top clockwise): [i] a Sanskrit manuscript from Turkestan,

[ii] another from Miran-China, [iii] the Kukai calligraphy of Siddham-Sanskrit

in Japan, [iv] a Sanskrit inscription in Cambodia, [v] the Thai

script, and [vi] a bell with Sanskrit engravings in South Korea.

There has been a profound influence of Sanskrit on the lexical and grammatical systems of Dravidian languages. As per Dalby, India has been a single cultural area for about two millennia which has helped Sanskrit influence on all the Indic languages. Emeneau and Burrow mention the tendency “for all four of the Dravidian literary languages in South to make literary use of total Sanskrit lexicon indiscriminately”. There are a large number of loanwords found in the vocabulary of the three major Dravidian languages Malayalam, Kannada and Telugu. Tamil also has significant loanwords from Sanskrit. Krishnamurthi mentions that although it is not clear when the Sanskrit influence happened on the Dravidian languages, it can perhaps be around 5th century BCE at the time of separation of Tamil and Kannada from a proto-dravidian language. The borrowed words are classified into two types based on phonological integration – tadbhava – those words derived from Prakrit and tatsama – unassimilated loanwords from Sanskrit.

Strazny mentions that “so massive has been the influence that it is hard to utter Sanskrit words have influenced Kannada from the early times”. The first document in Kannada, the Halmidi inscription has a large number of Sanskrit words. As per Kachru, the influence has not only been on single lexical items in Kannada but also on “long nominal compounds and complicated syntactic expressions”. New words have been created in Kannada using Sanskrit derivational prefixes and suffixes like vike:ndri:karaNa, anili:karaNa, bahi:skruTa. Similar stratification is found in verb morphology. Sanskrit words readily undergo verbalization in Kannada, verbalizing suffixes as in: cha:pisu, dowDa:yisu, rava:nisu.

George mentions that “no other Dravidian language has been so deeply influenced by Sanskrit as Malayalam”. Loanwords have been integrated into Malayalam by “prosodic phonological” changes as per Grant. These phonological changes are either by replacement of a vowel as in Sant-am coming from Sanskrit Santa-h, Sagar-am from Sagara-h, or addition of prothetic vowel as in aracan from rajan, uruvam from rupa, codyam from sodhya.

Hans Henrich et al. note that, the language of the pre-modern Telugu literature was also highly influenced by Sanskrit and was standardized between 11th and 14th centuries. Aiyar has shown that in a class of tadbhavas in Telugu the first and second letters are often replaced by the third and fourth letters and fourth again replaced often by h. Examples of the same are: Sanskrit arthah becomes ardhama, vithi becomes vidhi, putrah becomes bidda, mukham becomes muhamu.

Tamil language also has been influenced from Sanskrit. Hans Henrich et al. mention that propagation of Jainism and Buddhism into south India had its influence on Old Tamil Cankam Anthologies, Sanskrit poetical literature influenced Old Tamil literature Cilappatikaram and Maniemakalai. Middle Tamil has shown a significantly higher influence of Sanskrit into the Bhakti poems. Shulman mentions that although contrary to the views held by Tamil purists, modern Tamil has been significantly influenced from Sanskrit, further states that "Indeed there may well be more Sanskrit in Tamil than in the Sanskrit derived north-Indian vernaculars". Sanskrit words have been Tamilized through the "Tamil phonematic grid".

Interaction

with other languages :

Sanskrit has also influenced Sino-Tibetan languages, mostly through translations of Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit. Many terms were transliterated directly and added to the Chinese vocabulary. Chinese words like chànà (Devanagari: ksana 'instantaneous period') were borrowed from Sanskrit. Many Sanskrit texts survive only in Tibetan collections of commentaries to the Buddhist teachings, the Tengyur.

Sanskrit was a language for religious purposes and for the political elite in parts of medieval era Southeast Asia, Central Asia and East Asia. In Southeast Asia, languages such as Thai and Lao contain many loanwords from Sanskrit, as does Khmer. Many Sanskrit loanwords are also found in Austronesian languages, such as Javanese, particularly the older form in which nearly half the vocabulary is borrowed. Other Austronesian languages, such as traditional Malay and modern Indonesian, also derive much of their vocabulary from Sanskrit. Similarly, Philippine languages such as Tagalog have some Sanskrit loanwords, although more are derived from Spanish. A Sanskrit loanword encountered in many Southeast Asian languages is the word bha?a, or spoken language, which is used to refer to the names of many languages. English also has words of Sanskrit origin.

Sanskrit has also influenced the religious register of Japanese mostly through transliterations. These were borrowed from Chinese transliterations. In particular, the Shingon (lit. 'True Words') sect of esoteric Buddhism has been relying on Sanskrit and original Sanskrit mantras and writings, as a means of realizing Buddhahood.

Modern

era :

Many Hindu rituals and rites-of-passage such as the "giving away the bride" and mutual vows at weddings, a baby's naming or first solid food ceremony and the goodbye during a cremation invoke and chant Sanskrit hymns. Major festivals such as the Durga Puja ritually recite entire Sanskrit texts such as the Devi Mahatmya every year particularly amongst the numerous communities of eastern India. In the south, Sanskrit texts are recited at many major Hindu temples such as the Meenakshi Temple. According to Richard H. Davis, a scholar of Religion and South Asian studies, the breadth and variety of oral recitations of the Sanskrit text Bhagavad Gita is remarkable. In India and beyond, its recitations include "simple private household readings, to family and neighborhood recitation sessions, to holy men reciting in temples or at pilgrimage places for passersby, to public Gita discourses held almost nightly at halls and auditoriums in every Indian city".

Literature

and arts :

The Sahitya Akademi has given an award for the best creative work in Sanskrit every year since 1967. In 2009, Satya Vrat Shastri became the first Sanskrit author to win the Jnanpith Award, India's highest literary award.

Sanskrit is used extensively in the Carnatic and Hindustani branches of classical music. Kirtanas, bhajans, stotras, and shlokas of Sanskrit are popular throughout India. The samaVed uses musical notations in several of its recessions.

In Mainland China, musicians such as Sa Dingding have written pop songs in Sanskrit.

Numerous loan Sanskrit words are found in other major Asian languages. For example, Filipino,Cebuano, Lao, Khmer Thai and its alphabets, Malay, Indonesian (old Javanese-English dictionary by P.J. Zoetmulder contains over 25,500 entries), and even in English.

Media

:

Over 90 weeklies, fortnightlies and quarterlies are published in Sanskrit. Sudharma, a daily printed newspaper in Sanskrit, has been published out of Mysore, India, since 1970. It was started by K.N. Varadaraja Iyengar, a Sanskrit scholar from Mysore. Sanskrit Vartman Patram and Vishwasya Vrittantam started in Gujarat during the last five years.

Schools and contemporary status :

Sanskrit has been taught in schools from time immemorial in India. In modern times, the first Sanskrit University was Sampurnanand Sanskrit University, established in 1791 in the Indian city of Varanasi. Sanskrit is taught in 5,000 traditional schools (Pathashalas), and 14,000 schools in India, where there are also 22 colleges and universities dedicated to the exclusive study of the language. [citation needed] Sanskrit is one the 22 scheduled languages of India. Despite it being a studied school subject in contemporary India, Sanskrit is scarce as a first language. In the 2001 Census of India, 14,135 Indians reported Sanskrit to be their mother tongue, while in the 2011 census, 24,821 people out of about 1.21 billion reported this to be the case. According to the 2011 national census of Nepal, 1,669 people use Sanskrit as their first language.

The Central Board of Secondary Education of India (CBSE), along with several other state education boards, has made Sanskrit an alternative option to the state's own official language as a second or third language choice in the schools it governs. In such schools, learning Sanskrit is an option for grades 5 to 8 (Classes V to VIII). This is true of most schools affiliated with the Indian Certificate of Secondary Education (ICSE) board, especially in states where the official language is Hindi. Sanskrit is also taught in traditional gurukulas throughout India.

A number of colleges and universities in India have dedicated departments for Sanskrit studies.

In

the West :

European

studies and discourse :

The 18th- and 19th-century speculations about the possible links of Sanskrit to ancient Egyptian language were later proven to be wrong, but it fed an orientalist discourse both in the form Indophobia and Indophilia, states Trautmann. Sanskrit writings, when first discovered, were imagined by Indophiles to potentially be "repositories of the primitive experiences and religion of the human race, and as such confirmatory of the truth of Christian scripture", as well as a key to "universal ethnological narrative". (pp96–97) The Indophobes imagined the opposite, making the counterclaim that there is little of any value in Sanskrit, portraying it as "a language fabricated by artful [Brahmin] priests", with little original thought, possibly copied from the Greeks who came with Alexander or perhaps the Persians.(pp124–126)

Scholars such as William Jones and his colleagues felt the need for systematic studies of Sanskrit language and literature. This launched the Asiatic Society, an idea that was soon transplanted to Europe starting with the efforts of Henry Thomas Colebrooke in Britain, then Alexander Hamilton who helped expand its studies to Paris and thereafter his student Friedrich Schlegel who introduced Sanskrit to the universities of Germany. Schlegel nurtured his own students into influential European Sanskrit scholars, particularly through Franz Bopp and Friedrich Max Muller. As these scholars translated the Sanskrit manuscripts, the enthusiasm for Sanskrit grew rapidly among European scholars, states Trautmann, and chairs for Sanskrit "were established in the universities of nearly every German statelet" creating a competition for Sanskrit experts. (pp133–142)

Symbolic

usage :

•

India : Satyameva

Jayate meaning: Truth alone triumphs.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg)