| SCYTHIA

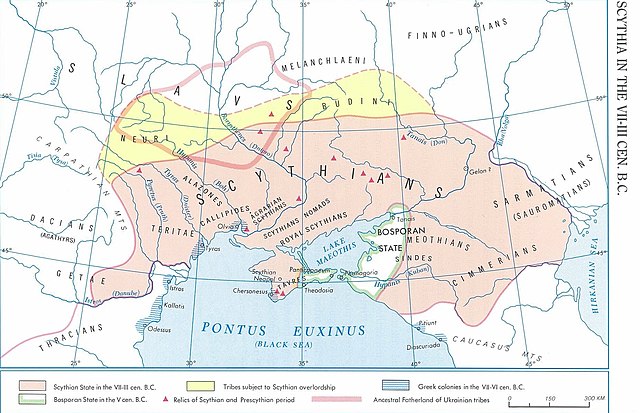

Approximate extent of Scythia within the area of distribution of Eastern Iranian languages (shown in orange) in the 1st century BC Scythia (Romanized: Skythike) was a region of Central Eurasia in classical antiquity, occupied by the Eastern Iranian Scythians, encompassing Central Asia, parts of Eastern Europe east of the Vistul River with the eastern edges of the region vaguely defined by the Greeks. The Ancient Greeks gave the name Scythia (or Great Scythia) to all the lands north-east of Europe and the northern coast of the Black Sea. During the Iron Age the region saw the flourishing of Scythian cultures.

The Scythians – the Greeks' name for this initially nomadic people – inhabited Scythia from at least the 11th century BC to the 2nd century AD. In the seventh century BC, the Scythians controlled large swaths of territory throughout Eurasia, from the Black Sea across Siberia to the borders of China. Its location and extent varied over time, but it usually extended farther to the west and significantly farther to the east than is indicated on the map. Some sources document that the Scythians were energetic but peaceful people. Not much is known about them.

Scythia was a loose nomadic empire that originated as early as 8th century BC. The core of Scythians preferred a free-riding way of life. No writing system that dates to the period has ever been attested, so majority of written information available today about the region and its inhabitants at the time stems from protohistorical writings of ancient civilizations which had connections to the region, primarily those of Ancient Greece, Ancient Rome and Ancient Persia. The most detailed western description is by Herodotus. He may not have travelled in Scythia and there is scholarly debate as to the accuracy of his knowledge, but modern archaeological finds have confirmed some of his ancient claims and he remains one of the most useful writers on ancient Scythia. He says the Scythians' own name for themselves was "Scoloti".

Geography

:

•

The Pontic–Caspian

steppe: South-Eastern Ukraine, Southern Russia, Russian Volga, South-Ural

regions and western Kazakhstan (inhabited by Scythians from at least

the 8th century BC)

Scythia in the VII–III cen. BC (1995)

First Scythian kingdom :

It is possible that the same dynasty ruled in Scythia during most of its history. The name of Koloksai, a legendary founder of a royal dynasty, is mentioned by Alcman in the seventh century BC. Prototi and Madius, Scythian kings in the Near Eastern period of their history, and their successors in the north Pontic steppes belonged to the same dynasty. Herodotus lists five generations of a royal clan that probably reigned at the end of the seventh to sixth centuries BC: prince Anacharsis, Saulius, Idanthyrsus, Gnurus [ru], Lycus [uk], and Spargapeithes.

After being defeated and driven from the Near East, in the first half of the sixth century BC, Scythians had to reconquer lands north of the Black Sea. In the second half of that century, Scythians succeeded in dominating the agricultural tribes of the forest steppe and placed them under tribute. As a result, their state was reconstructed with the appearance of the Second Scythian Kingdom which reached its zenith in the fourth century BC.

Second Scythian kingdom :

Coat of arms of Schythia (Thesouro de Nobreza, 1675) Scythia's social development at the end of the 5th century BC and in the 4th century BC was linked to its privileged status of trade with Greeks, its efforts to control this trade, and the consequences partly stemming from these two. Aggressive external policy intensified exploitation of dependent populations and progressed the stratification among the nomadic rulers. Trading with Greeks also stimulated sedentarization processes.

The proximity of the Greek city-states on the Black Sea coast (Pontic Olbia, Cimmerian Bosporus, Chersonesos, Sindica, Tanais) was a powerful incentive for slavery in the Scythian society, but only in one direction: the sale of slaves to Greeks, instead of use in their economy. Accordingly, the trade became a stimulus for capture of slaves as war spoils in numerous wars.

Scythia

from the late 5th to 3rd centuries BC :

Written sources recount that before the 4th century BC the Scythian state expanded mainly to the west. In this respect Ateas continued the policy of his predecessors in the 5th century BC. During western expansion, Ateas fought the Triballi. An area of Thrace was subjugated and levied with severe duties. During the 90-year life of Ateas (c. 429 BC – 339 BC) the Scythians settled firmly in Thrace and became an important factor in the politics of the Balkans. At the same time, both the nomadic and agricultural Scythian populations increased along the Dniester river. A war with the Bosporian Kingdom increased Scythian pressure on the Greek cities along the North Pontic littoral.

Materials from the site near Kamianka-Dniprovska, purportedly the capital of Ateas' state, show that metallurgists were free members of the society, even if burdened with imposed obligations. Metallurgy was the most advanced and the only distinct craft speciality among the Scythians. From the story of Polyaenus and Frontin, it follows that in the 4th century BC Scythia had a layer of dependent population, which consisted of impoverished Scythian nomads and local indigenous agricultural tribes, socially deprived, dependent and exploited, who did not participate in the wars, but were engaged in servile agriculture and cattle husbandry.

The year 339 BC proved a culminating year for the Second Scythian Kingdom, and the beginning of its decline. The war with Philip II of Macedon ended in a victory for Philip (the father of Alexander the Great). The Scythian king Ateas fell in battle well into his nineties. Many royal kurgans (Chertomlyk, Kul-Oba, Aleksandropol, Krasnokut) date from after Ateas's time and previous traditions were continued; and life in the settlements of Western Scythia show that the state survived until the 250s BC. When in 331 BC Zopyrion, Alexander's viceroy in Thrace, "not wishing to sit idle", invaded Scythia and besieged Pontic Olbia, he suffered a crushing defeat at the hands of the Scythians and lost his life.

The fall of the Second Scythian Kingdom came about in the second half of the 3rd century BC under the onslaught of Celts and Thracians from the west and of Sarmatians from the east. With their increased forces, the Sarmatians devastated significant parts of Scythia and, "annihilating the defeated, transformed a larger part of the country into a desert".

The dependent forest-steppe tribes, subjected to exaction burdens, freed themselves at the first opportunity. [citation needed] The Dnieper and Southern Bug populace ruled by the Scythians did not become Scythians. They continued to live their original life, which was alien to Scythian ways. From the 3rd century BC for many centuries the histories of the steppe and forest-steppe zones of the North Pontic area diverged. The material cultures of the populations quickly lost their common features. And in the steppe, reflecting the end of nomad hegemony in Scythian society, the royal kurgans were no longer built. Archeologically, late Scythia appears first of all as a conglomerate of fortified and non-fortified settlements with abutting agricultural zones.

The development of Scythian society featured the following trends :

•

The process of

settlement intensified, as evidenced by the appearance of numerous

kurgan burials in the steppe zone of the North Pontic-Caspian steppe.

Some of them date to the end of the 5th century BC, but the majority

belong to the 4th or 3rd centuries BC, reflecting the establishment

of permanent pastoral coaching routes and a tendency to semi-nomadic

pasturing. The Lower Dnieper area contained mostly unfortified settlements,

while in Crimea and Western Scythia the agricultural population

grew. The Dnieper settlements developed in what were previously

nomadic winter villages, and in uninhabited lands.

Later Scythian kingdoms :

Scythia et Serica, 18th century map Having settled this Scythia Minor in Thrace, the former Scythian nomads (or rather their nobility) abandoned their nomadic way of life, retaining their power over the agrarian population. This little polity should be distinguished from the Third Scythian Kingdom in Crimea and Lower Dnieper area, whose inhabitants likewise underwent a massive sedentarization. The interethnic dependence was replaced by developing forms of dependence within the society.

The enmity of the Third Scythian Kingdom, centred on Scythian Neapolis, towards the Greek settlements of the northern Black Sea steadily increased. The Scythian king apparently regarded the Greek colonies as unnecessary intermediaries in the wheat trade with mainland Greece. Besides, the settling cattlemen were attracted by the Greek agricultural belt in Southern Crimea. The later Scythia was both culturally and socio-economically far less advanced than its Greek neighbors such as Olvia or Chersonesos.

The continuity of the royal line is less clear in the Lesser Scythias of Crimea and Thrace than it had been previously. In the 2nd century BC, Olvia became a Scythian dependency. That event was marked in the city by minting of coins bearing the name of the Scythian king Skilurus. He was a son of a king and a father of a king, but the relation of his dynasty with the former dynasty is not known. Either Skilurus or his son and successor Palakus were buried in the mausoleum of Scythian Neapol that was used from c. 100 BC to c. 100 AD. However, the last burials are so poor that they do not seem to be royal, indicating a change in the dynasty or royal burials in another place.

Later, at the end of the 2nd century BC, Olvia was freed from Scythian domination, but became a subject to Mithridates I of Parthia. By the end of the 1st century BC, Olbia, rebuilt after its sack by the Getae, became a dependency of the Dacian barbarian kings, who minted their own coins in the city. Later from the 2nd century AD Olbia belonged to the Roman Empire. Scythia was the first state north of the Black Sea to collapse with the invasion of the Goths in the 2nd century AD (see Oium). At the end of the 2nd century AD, King Sauromates II critically defeated the Scythians and included the Crimea into his Kingdom of the Cimmerian Bosporus, a Roman client state.

Scythian kings :

Scythian king Skilurus, relief from Scythian Neapolis, Crimea, 2nd century BC

• Ariapeithes

(or Ariapifa) (c. 500 BC) – was a Scythian king

•

Androphagi

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |