| STRABO

Strabo as depicted in a 16th Century engraving Born

: 64 or 63 BC Amaseia, Pontus (modern-day Amasya, Turkey)

Strabo (Greek: Strábon; 64 or 63 BC – c. AD 24) was a Greek geographer, philosopher, and historian who lived in Asia Minor during the transitional period of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire.

Life :

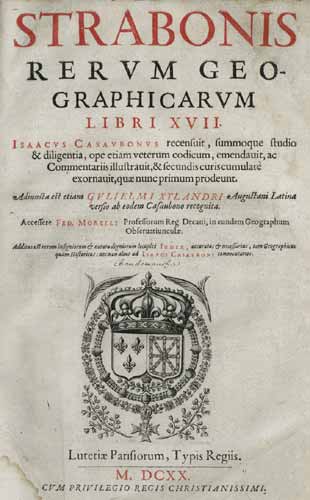

Title page from Isaac Casaubon's 1620 edition of Geographica Strabo was born to an affluent family from Amaseia in Pontus (in present-day Turkey) in around 64 BC. His family had been involved in politics since at least the reign of Mithridates V. Strabo was related to Dorylaeus on his mother's side. Several other family members, including his paternal grandfather had served Mithridates VI during the Mithridatic Wars. As the war drew to a close, Strabo's grandfather had turned several Pontic fortresses over to the Romans. Strabo wrote that "great promises were made in exchange for these services", and as Persian culture endured in Amaseia even after Mithridates and Tigranes were defeated, scholars have speculated about how the family's support for Rome might have affected their position in the local community, and whether they might have been granted Roman citizenship as a reward.

Strabo as depicted in the Nuremberg Chronicle Strabo's life was characterized by extensive travels. He journeyed to Egypt and Kush, as far west as coastal Tuscany and as far south as Ethiopia in addition to his travels in Asia Minor and the time he spent in Rome. Travel throughout the Mediterranean and Near East, especially for scholarly purposes, was popular during this era and was facilitated by the relative peace enjoyed throughout the reign of Augustus (27 BC – AD 14). He moved to Rome in 44 BC, and stayed there, studying and writing, until at least 31 BC. In 29 BC, on his way to Corinth (where Augustus was at the time), he visited the island of Gyaros in the Aegean Sea. Around 25 BC, he sailed up the Nile until he reached Philae, after which point there is little record of his travels until AD 17.

Statue of Strabo in his hometown (modern-day Amasya, Turkey), beside the Iris (Yesilirmak) River It is not known precisely when Strabo's Geography was written, though comments within the work itself place the finished version within the reign of Emperor Tiberius. Some place its first drafts around 7 BC, others around AD 17 or AD 18. The latest passage to which a date can be assigned is his reference to the death in AD 23 of Juba II, king of Maurousia (Mauretania), who is said to have died "just recently". He probably worked on the Geography for many years and revised it steadily, but not always consistently. It is an encyclopaedic chronicle and consists of political, economic, social, cultural, geographic description covering almost all of Europe and the Mediterranean: British Isles, Iberian Peninsula, Gaul, Germania, the Alps, Italy, Greece, Northern Black Sea region, Anatolia, Middle East, Central Asia and North Africa. The Geography is the only extant work providing information about both Greek and Roman peoples and countries during the reign of Augustus.

On the presumption that "recently" means within a year, Strabo stopped writing that year or the next (AD 24), at which time he is thought to have died. He was influenced by Homer, Hecataeus and Aristotle. The first of Strabo's major works, Historical Sketches (Historica hypomnemata), written while he was in Rome (c. 20 BC), is nearly completely lost. Meant to cover the history of the known world from the conquest of Greece by the Romans, Strabo quotes it himself and other classical authors mention that it existed, although the only surviving document is a fragment of papyrus now in the possession of the University of Milan (renumbered [Papyrus] 46).

Education

:

At around the age of 21, Strabo moved to Rome, where he studied philosophy with the Peripatetic Xenarchus, a highly respected tutor in Augustus's court. Despite Xenarchus's Aristotelian leanings, Strabo later gives evidence to have formed his own Stoic inclinations. In Rome, he also learned grammar under the rich and famous scholar Tyrannion of Amisus. Although Tyrannion was also a Peripatetic, he was more relevantly a respected authority on geography, a fact of some significance considering Strabo's future contributions to the field.

The final noteworthy mentor to Strabo was Athenodorus Cananites, a philosopher who had spent his life since 44 BC in Rome forging relationships with the Roman elite. Athenodorus passed onto Strabo his philosophy, his knowledge and his contacts. Unlike the Aristotelian Xenarchus and Tyrannion who preceded him in teaching Strabo, Athenodorus was a Stoic and almost certainly the source of Strabo's diversion from the philosophy of his former mentors. Moreover, from his own first-hand experience, Athenodorus provided Strabo with information about regions of the empire which Strabo would not otherwise have known about.

Geographica :

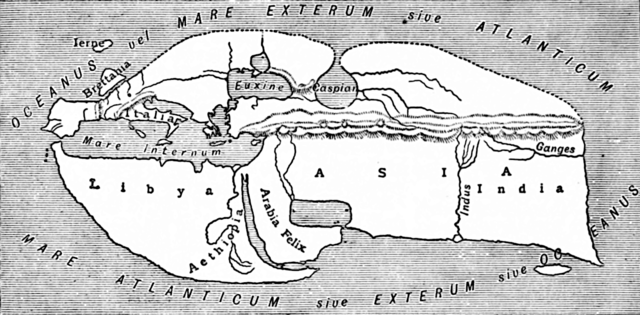

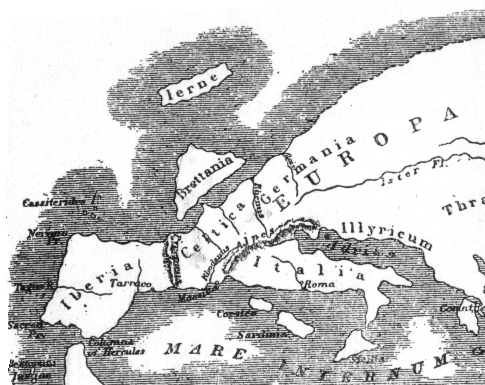

Map

of the world according to Strabo

Strabo is best known for his work Geographica ("Geography"), which presented a descriptive history of people and places from different regions of the world known during his lifetime.

Map of Europe according to Strabo Although the Geographica was rarely utilized by contemporary writers, a multitude of copies survived throughout the Byzantine Empire. It first appeared in Western Europe in Rome as a Latin translation issued around 1469. The first Greek edition was published in 1516 in Venice. Isaac Casaubon, classical scholar and editor of Greek texts, provided the first critical edition in 1587.

Although Strabo cited the classical Greek astronomers Eratosthenes and Hipparchus, acknowledging their astronomical and mathematical efforts covering geography, he claimed that a descriptive approach was more practical, such that his works were designed for statesmen who were more anthropologically than numerically concerned with the character of countries and regions.

As such, Geographica provides a valuable source of information on the ancient world of his day, especially when this information is corroborated by other sources. He travelled extensively, as he says: "Westward I have journeyed to the parts of Etruria opposite Sardinia; towards the south from the Euxine to the borders of Ethiopia; and perhaps not one of those who have written geographies has visited more places than I have between those limits."

It is not known when he wrote Geographica, but he spent much time in the famous library in Alexandria taking notes from "the works of his predecessors". A first edition was published in 7 BC and a final edition no later than 23 AD, in what may have been the last year of Strabo's life. It took some time for Geographica to be recognized by scholars and for Geographica to become a standard. In his last book of Geographica, he wrote quite extensively about the thriving port city of Alexandria suggesting a highly developed local economy at that time.

Strabo also describes the city of Alexandria noting that there were many beautiful public parks and the city was reticulated with streets wide enough for chariots and horsemen. "Two of these are exceeding broad, over a plethron in breadth, and cut one another at right angles ... All the buildings are connected one with another, and these also with what are beyond it."

Lawrence Kim observes that Strabo is "... pro-Roman throughout the Geography. But while he acknowledges and even praises Roman ascendancy in the political and military sphere, he also makes a significant effort to establish Greek primacy over Rome in other contexts."

In Europe, Strabo was the first to connect the Danube -- Danouios and the Istros --with the change of names occurring at "the cataracts," the modern Iron Gates on the Romanian/Serbian border.

In India, a country he never visited, Strabo described small flying reptiles that were long with a snake-like body and bat-like wings, winged scorpions, and other mythical creatures along with those that were factual. Other historians, such as Herodotus, Aristotle, and Flavius Josephus, mentioned similar creatures.[citation needed]

Geology

:

Strabo…enters

largely, in the Second Book of his Geography, into the opinions

of Eratosthenes and other Greeks on one of the most difficult problems

in geology, viz., by what causes marine shells came to be plentifully

buried in the earth at such great elevations and distances from

the sea.

But Strabo rejects this theory as insufficient to account for all the phenomena, and he proposes one of his own, the profoundness of which modern geologists are only beginning to appreciate. 'It is not,' he says, 'because the lands covered by seas were originally at different altitudes, that the waters have risen, or subsided, or receded from some parts and inundated others. But the reason is, that the same land is sometimes raised up and sometimes depressed, and the sea also is simultaneously raised and depressed so that it either overflows or returns into its own place again. We must, therefore, ascribe the cause to the ground, either to that ground which is under the sea, or to that which becomes flooded by it, but rather to that which lies beneath the sea, for this is more moveable, and, on account of its humidity, can be altered with great celerity. It is proper,' he observes in continuation, 'to derive our explanations from things which are obvious, and in some measure of daily occurrences, such as deluges, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and sudden swellings of the land beneath the sea; for the last raise up the sea also, and when the same lands subside again, they occasion the sea to be let down. And it is not merely the small, but the large islands also, and not merely the islands, but the continents, which can be lifted up together with the sea; and both large and small tracts may subside, for habitations and cities, like Bure, Bizona, and many others, have been engulfed by earthquakes.'

In another place, this learned geographer [Strabo], in alluding to the tradition that Sicily had been separated by a convulsion from Italy, remarks, that at present the land near the sea in those parts was rarely shaken by earthquakes, since there were now open orifices whereby fire and ignited matters and waters escaped; but formerly, when the volcanoes of Etna, the Lipari Islands, Ischia, and others, were closed up, the imprisoned fire and wind might have produced far more vehement movements. The doctrine, therefore, that volcanoes are safety valves, and that the subterranean convulsions are probably most violent when first the volcanic energy shifts itself to a new quarter, is not modern.

Fossil

formation :

One extraordinary thing which I saw at the pyramids must not be omitted. Heaps of stones from the quarries lie in front of the pyramids. Among these are found pieces which in shape and size resemble lentils. Some contain substances like grains half peeled. These, it is said, are the remnants of the workmen's food converted into stone; which is not probable. For at home in our country (Amaseia), there is a long hill in a plain, which abounds with pebbles of a porous stone, resembling lentils. The pebbles of the sea-shore and of rivers suggest somewhat of the same difficulty [respecting their origin]; some explanation may indeed be found in the motion [to which these are subject] in flowing waters, but the investigation of the above fact presents more difficulty. I have said elsewhere, that in sight of the pyramids, on the other side in Arabia, and near the stone quarries from which they are built, is a very rocky mountain, called the Trojan mountain; beneath it there are caves, and near the caves and the river a village called Troy, an ancient settlement of the captive Trojans who had accompanied Menelaus and settled there.

Volcanism

:

…There are no trees here, but only the vineyards where they produce the Katakekaumene wines which are by no means inferior from any of the wines famous for their quality. The soil is covered with ashes, and black in colour as if the mountainous and rocky country was made up of fires. Some assume that these ashes were the result of thunderbolts and subterranean explosions, and do not doubt that the legendary story of Typhon takes place in this region. Ksanthos adds that the king of this region was a man called Arimus. However, it is not reasonable to accept that the whole country was burned down at a time as a result of such an event rather than as a result of a fire bursting from underground whose source has now died out. Three pits are called "Physas" and separated by forty stadia from each other. Above these pits, there are hills formed by the hot masses burst out from the ground as estimated by a logical reasoning. Such type of soil is very convenient for viniculture, just like the Katanasoil which is covered with ashes and where the best wines are still produced abundantly. Some writers concluded by looking at these places that there is a good reason for calling Dionysus by the name ("Phrygenes").

Editions

:

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |