| TOCHARIANS

Probable Tocharian donors, from the Kizilgaha caves near Kucha, 6th century AD. They appear Europoid, and have Sasanian-style dress. These paintings are associated with annotations in Tocharian and Sanskrit made by their painters.

Regions

with significant populations : Tarim Basin in 1st millennium

AD (modern Xinjiang, China)

The Tocharians, or Tokharians, were speakers of Tocharian languages, Indo-European languages known from around 7600 documents from around 400 to 1200 AD, found on the northern edge of the Tarim Basin (modern Xinjiang, China). The name "Tocharian" was given to these languages in the early 20th century by scholars who identified their speakers with a people known in ancient Greek sources as the Tókharoi (Latin Tochari), who inhabited Bactria from the 2nd century BC. This identification is generally considered erroneous, but the name "Tocharian" remains the most common term for the languages and their speakers. Their actual ethnic name is unknown, although they may have referred to themselves as Agni, Kuci and Krorän, or Agniya, Kuchiya as known from Sanskrit texts.

Agricultural communities first appeared in the oases of the northern Tarim circa 2000 BC. (The earliest Tarim mummies, which may not be connected to the Tocharians, date from c. 1800 BC.) Some scholars have linked these communities to the Afanasievo culture found earlier (c. 3500–2500 BC) in Siberia, north of the Tarim or Central Asian BMAC culture.

By the 2nd century BC, these settlements had developed into city-states, overshadowed by nomadic peoples to the north and Chinese empires to the east. These cities, the largest of which was Kucha, also served as way stations on the branch of the Silk Road that ran along the northern edge of the Taklamakan desert.

From the 8th century AD, the Uyghurs – speakers of a Turkic language from the Kingdom of Qocho – settled in the region. The peoples of the Tarim city-states intermixed with the Uyghurs, whose Old Uyghur language spread through the region. The Tocharian languages are believed to have become extinct during the 9th century.

Names

:

•

A Buddhist work

in Old Turkic (Uighur), included a colophon stating that the text

had been translated from Sanskrit via toxrï tyly ("The

language of the Togari").

Müller's identification became a minority position among scholars when it turned out that the people of Tokharistan (Bactria) spoke Bactrian, an Eastern Iranian language, which is quite distinct from the Tocharian languages. Nevertheless, "Tocharian" remained the standard term for the languages of the Tarim Basin manuscripts and for the people who produced them. A few scholars still affirm that the "Tocharians" and the Yuezhi are identical, attributing the Bactrian language of the Yuezhi to a later adoption.

The name of Kucha in Tocharian B was Kusi, with adjectival form kusiññe. The word may be derived from Proto-Indo-European *keuk "shining, white". The Tocharian B word akeññe may have referred to people of Agni, with a derivation meaning "borderers, marchers". One of the Tocharian A texts has arsi-käntwa as a name for their own language, so that arsi may have meant "Agnean", though "monk" is also possible.

Languages :

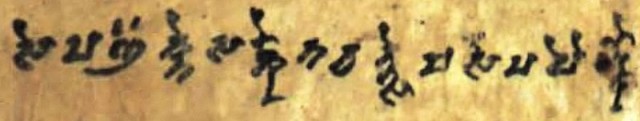

The

Tocharian script is very similar to the Indian Brahmi script from

the Kushan period. Tocharian language inscription: Se pañäkte

sanketavattse sarsa papaiykau "This Buddha was painted by the

hand of Sanketav", on a painting carbon dated to 245-340 AD.

Tocharian A (Agnean or East Tocharian) was found in the northeastern oases known to the Tocharians as Arsi, later Agni (i.e. Chinese Yanqi; modern Karasahr) and Turpan (including Khocho or Qoco; known in Chinese as Gaochang). Some 500 manuscripts have been studied in detail, mostly coming from Buddhist monasteries. Many authors take this to imply that Tocharian A had become a purely literary and liturgical language by the time of the manuscripts, but it may be that the surviving documents are unrepresentative.

Tocharian B (Kuchean or West Tocharian) was found at all the Tocharian A sites and also in several sites further west, including Kuchi (later Kucha). It appears to have still been in use in daily life at that time. Over 3200 manuscripts have been studied in detail.

The languages had significant differences in phonology, morphology and vocabulary, making them mutually unintelligible "at least as much as modern Germanic or Romance languages". Tocharian A shows innovations in the vowels and nominal inflection, whereas Tocharian B has changes in the consonants and verbal inflection. Many of the differences in vocabulary between the languages concern Buddhist concepts, which may suggest that they were associated with different Buddhist traditions.

The differences indicate that they diverged from a common ancestor between 500 and 1000 years before the earliest documents, that is, some time in the 1st millennium BC. Common Indo-European vocabulary retained in Tocharian includes words for herding, cattle, sheep, pigs, dogs, horses, textiles, farming, wheat, gold, silver, and wheeled vehicles.

Prakrit documents from 3rd century Krorän, Andir and Niya on the southeast edge of the Tarim Basin contain around 100 loanwords and 1000 proper names that cannot be traced to an Indic or Iranian source. Thomas Burrow suggested that they come from a variety of Tocharian, dubbed Tocharian C or Kroränian, which may have been spoken by at least some of the local populace. Burrow's theory is widely accepted, but the evidence is meagre and inconclusive, and some scholars favour alternative explanations.

Origins :

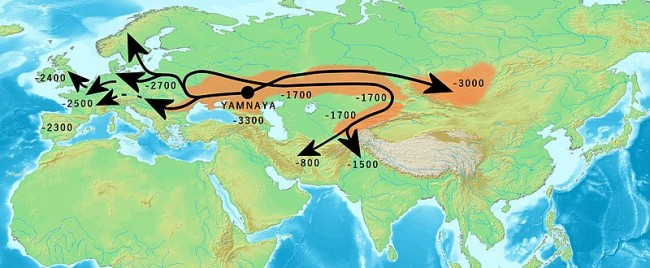

J. P. Mallory and Victor H. Mair argue that the Tarim was first settled by Proto-Tocharian-speakers from the Afanasevo culture to the north, who migrated to the south and occupied the northern and eastern edges of the Tarim Basin. The Afanasevo culture itself resulted from the eastward migration of the Yamnaya culture, originally based in the Pontic steppe north of the Caucasus Mountains. The Afanasevo culture (c. 3500–2500 BC) displays cultural and genetic connections with the Indo-European-associated cultures of the Central Asian steppe yet predates the specifically Indo-Iranian-associated Andronovo culture (c. 2000–900 BC). The early eastward expansion of the Yamnaya culture circa 3300 BC is enough to account for the isolation of the Tocharian languages from Indo-Iranian linguistic innovations like satemization.

Settlement

of the Tarim basin :

The necessary irrigation technology was first developed during the 3rd millennium BC in the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC) to the west of the Pamir mountains, but it is unclear how it reached the Tarim. The staple crops, wheat and barley, also originated in the west.

Tarim mummies :

One of the Tarim mummies

"Loulan beauty" The oldest of the Tarim mummies, bodies preserved by the desert conditions, date from 2000 BC and were found on the eastern edge of the Tarim basin. They seem to be Caucasoid types with light-colored hair. A genetic study of remains from the oldest layer of the Xiaohe Cemetery found that the maternal lineages were a mixture of east and west Eurasian types, while all the paternal lineages were of west Eurasian type. It is unknown whether they are connected with the frescoes painted at Tocharian sites more than two millennia later, which also depict light eyes and hair color.

Later, groups of nomadic pastoralists moved from the steppe into the grasslands to the north and northeast of the Tarim. They were the ancestors of peoples later known to Chinese authors as the Wusun and Yuezhi. At least some of them spoke Iranian languages, but a minority of scholars suggest that the Yuezhi were Tocharian speakers.

During the 1st millennium BC, a further wave of immigrants, the Saka speaking Iranian languages, arrived from the west and settled along the southern rim of the Tarim. They are believed to be the source of Iranian loanwords in Tocharian languages, particularly related to commerce and warfare.

Religion

:

Oasis states :

Major oasis states of the ancient Tarim Basin The first record of the oasis states is found in Chinese histories. The Book of Han lists 36 statelets in the Tarim basin in the last two centuries BC. These oases served as waystations on the trade routes forming part of the Silk Road passing along the northern and southern edges of the Taklamakan desert. The largest were Kucha with 81,000 inhabitants and Agni (Yanqi or Karashar) with 32,000. Chinese histories give no evidence of ethnic changes in these cities between that time and the period of the Tocharian manuscripts from these sites. Situated on the northern edge of the Tarim, these small urban societies were overshadowed by nomadic peoples to the north and Chinese empires to the east. They conceded tributary relations with the larger powers when required, and acted independently when they could.

Xiongnu

and Han empire :

Flourishing

of the oasis states :

They have a walled city and suburbs. The walls are threefold. Within are Buddhist temples and stupas numbering a thousand. The people are engaged in agriculture and husbandry. The men and women cut their hair and wear it at the neck. The prince's palace is grand and imposing, glittering like an abode of the gods.

—

Book of Jin, Chapter 97

Kushan Empire (2nd century AD) :

A bronze coin of Kanishka the Great found in Khotan, Tarim Basin. 2nd century AD

Kizil Caves paintings in Gandhar style, with Tocharian inscriptions. Carbon dated to 245 - 340 CE The Kushan Empire expanded into the Tarim during the 2nd century AD, bringing Buddhism, Kushan art, Sanskrit as a liturgical language and Prakrit as an administrative language (in the southern Tarim states). With these Indic languages came scripts, including the Brahmi script (later adapted to write Tocharian) and the Kharosthi script.

From the 3rd century, Kucha became a centre of Buddhist studies. Buddhist texts were translated into Chinese by Kuchean monks, the most famous of whom was Kumarajiva (344–412/5). Captured by Lü Guang of the Later Liang in an attack on Kucha in 384, Kumarajiva learned Chinese during his years of captivity in Gansu. In 401, he was brought to the Later Qin capital of Chang'an, where he remained as head of a translation bureau until his death in 413.

The Kizil Caves lie 65 km west of Kucha, and contain over 236 Buddhist temples. Their murals date from the 3rd to the 8th century. Many of these murals were removed by Albert von Le Coq and other European archaeologists in the early 20th century, and are now held in European museums, but others remain in their original locations.

An increasingly dry climate in the 4th and 5th centuries led to the abandonment of several of the southern cities, including Niya and Krorän, with a consequent shift of trade from the southern route to the northern one.Confederations of nomadic tribes also began to jostle for supremacy. The northern oasis states were conquered by Rouran in the late 5th century, leaving the local leaders in place.

Hephthalite conquest (circa 480 - 550 AD) :

An

early "Tocharian donors" mural, Qizil, Tarim Basin. This

painting was carbon dated to 432–538 CE. The style of the

swordsmen in single-lapel caftan is now considered to belong to

the Hephthalites, from Tokharistan, who occupied the Tarim Basin

from 480 to 560 CE, and spoke Bactrian, an Eastern Iranian language.

As the territories ruled by the Hephthalites expanded into Central Asia and the Tarim Basin, the art of the Hephthalites, with characteristic clothing and hairstyles, also came to be used in the areas they ruled, such as Sogdiana, Bamiyan or Kucha in the Tarim Basin (Kizil Caves, Kumtura Caves, Subashi reliquary). In these areas appear dignitaries with caftans with a triangular collar on the right side, crowns with three crescents, some crowns with wings, and a unique hairstyle. Another marker is the two-point suspension system for swords, which seems to have been an Hephthalite innovation, and was introduced by them in the territories they controled. The paintings from the Kucha region, particularly the swordmen in the Kizil Caves, appear to have been made during Hephthalite rule in the region, circa 480–550 CE. The influence of the art of Gandhar in some of the earliest paintings at the Kizil Caves, dated to circa 500 CE, is considered as a consequence of the political unification of the area between Bactria and Kucha under the Hephthalites.

Göktürks :

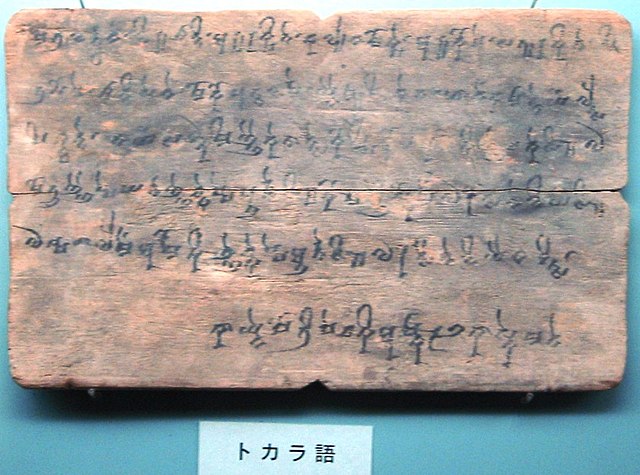

Wooden tablet describing a piece of land, Kucha, 6th – 7th century The early Turks of the First Turkic Khaganate then took control of the Turfan and Kucha areas from around 560 CE, and, in alliance with the Sasanian Empire, became instrumental in the fall of the Hepthalite Empire.

The Turks then split into western and eastern khaganates. The Bai family continued to rule Kucha, as vassals of the Western Turks. Many surviving texts in Tocharian date from this period, and deal with a wide variety of administrative, religious and everyday topics. They also include travel passes, small slips of poplar wood giving the size of the permitted caravans for officials at the next station along the road.

Tang

conquest and aftermath :

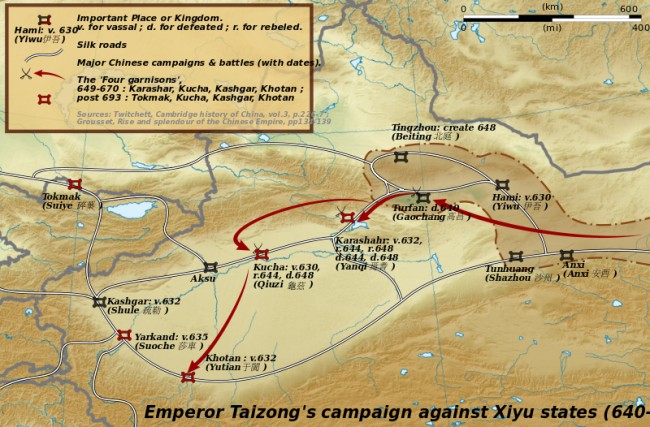

Emperor Taizong's campaign against the oasis states Next to the west lay the city of Agni, which had been a tributary of the Tang since 632. Alarmed by the nearby Chinese armies, Agni stopped sending Tribute to China and formed an alliance with the Western Turks. They were aided by Kucha, who also stopped sending tribute. The Tang captured Agni in 644, defeating a Western Turk relief force, and made the king resume tribute. When that king was deposed by a relative in 648, the Tang sent an army under the Turk general Ashina She'er to install a compliant member of the local royal family. Ashina She'er continued to capture Kucha, and made it the headquarters of the Tang Protectorate General to Pacify the West. Kuchean forces recaptured the city and killed protector-general, Guo Xiaoke, but it fell again to Ashina She'er, who had 11,000 of the inhabitants executed in reprisal for the killing of Guo. The Tocharian cities never recovered from the Tang conquest.

The Tang lost the Tarim basin to the Tibetan Empire in 670, but regained it in 692, and continued to rule there until it was recaptured by the Tibetans in 792. The ruling Bai family of Kucha are last mentioned in Chinese sources in 787. There is little mention of the region in Chinese sources for the 9th and 10th centuries.

The Uyghur Khaganate took control of the northern Tarim in 803. After their capital in Mongolia was sacked by the Yenisei Kyrgyz in 840, they established a new state, the Kingdom of Qocho with its capital at Gaochang (near Turfan) in 866. Over centuries of contact and intermarriage, the cultures and populations of the pastoralist rulers and their agriculturalist subjects blended together. The Uighurs abandoned their state religion of Manichaeism in favour of Buddhism, and adopted the agricultural lifestyle and many of the customs of the oasis-dwellers. The Tocharian language gradually disappeared as the urban population switched to the Old Uyghur language.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

.jpg)

.svg.jpg)

.jpg)