| WUSUN

Rider burial mound Tenlik (III.-II. B.C.) The Tenlik kurgan is associated with the Wusun The Wusun (Chinese: pinyin: Wusun; Eastern Han) were an Indo-European semi-nomadic steppe people mentioned in Chinese records from the 2nd century BC to the 5th century AD.

The Wusun originally lived between the Qilian Mountains and Dunhuang (Gansu) near the Yuezhi. Around 176 BC the Yuezhi were raided by the Xiongnu, who subsequently attacked the Wusun, killing their king and seizing their land. The Xiongnu adopted the surviving Wusun prince and made him one of their generals and leader of the Wusun. Around 162 BC the Yuezhi were driven into the Ili River valley in Zhetysu, Dzungaria and Tian Shan, which had formerly been inhabited by the Saka (Scythians). The Wusun then resettled in Gansu as vassals of the Xiongnu. In 133–132 BC, the Wusun drove the Yuezhi out of the Ili Valley and settled the area.

The Wusun then became close allies of the Han dynasty and remained a powerful force in the region for several centuries. The Wusun are last mentioned by the Chinese as having settled in the Pamir Mountains in the 5th century AD due to pressure from the Rouran. They possibly became subsumed into the later Hephthalites.

Etymology

:

Sinologist Victor H. Mair compared Wusun with Sanskrit ásva 'horse', asvin 'mare' and Lithuanian ašvà 'mare'. The name would thus mean 'the horse people'. Hence he put forward the hypothesis that the Wusun used a satem-like language within the Indo-European languages. However, the latter hypothesis is not supported by Edwin G. Pulleyblank. Christopher I. Beckwith's analysis is similar to Mair's, reconstructing the Chinese term Wusun as Old Chinese *âswin, which he compares to Old Indic asvin 'the horsemen', the name of the Rigvedic twin equestrian gods.

Étienne de la Vaissière identifies the Wusun with enemies of the Sogdian-speaking Kangju confederation, whom Sogdians mentioned on Kultobe inscriptions as wd'nn'p. Wd'nn'p contains two morpheme n'p "people" and *wd'n [wiðan], which is cognate with Manichaean Parthian wd'n and means "tent". Vaissière hypothesized that the Wusun likely spoke an Iranian language closely related to Sogdian, permitting Sogdians to translate their endonym as *wd'n [wiðan] and Chinese to transcribe their endonym with a native /s/ standing for a foreign dental fricative. Therefore, Vaissière reconstructs Wusun's endonym as "[People of the] Tent(s)".

History

:

Migration of the Wusun The Wusun were first mentioned by Chinese sources as living together with the Yuezhi between the Qilian Mountains and Dunhuang (Gansu), although different locations have been suggested for these toponyms. Beckwith suggests that the Wusun were an eastern remnant of the Indo-Aryans, who had been suddenly pushed to the extremities of the Eurasian Steppe by the Iranian peoples in the 2nd millennium BCE.

Around 210–200 BCE, prince Modu Chanyu, a former hostage of the Yuezhi and prince of the Xiongnu, who were also vassals of the Yuezhi, became leader of the Xiongnu and conquered the Mongolian Plain, subjugating several peoples. Around 176 BCE Modu Chanyu launched a fierce raid against the Yuezhi. Around 173 BCE, the Yuezhi subsequently attacked the Wusun, at that time a small nation, killing their king.

According to legend Nandoumi's infant son Liejiaomi was left in the wild. He was miraculously saved from hunger being suckled by a she-wolf, and fed meat by ravens. The Wusun ancestor myth shares striking similarities with those of the Hittites, the Zhou Chinese, the Scythians, the Romans, the Goguryeo, Turks, Mongols and Dzungars. Based on the similarities between the ancestor myth of the Wusun and later Turkic peoples, Denis Sinor has suggested that the Wusun, Sogdians, or both could represent an Indo-Aryan influence, or even the origin of the royal Ashina Türks.

In 162 BCE, the Yuezhi were finally defeated by the Xiongnu, after which they fled Gansu. According to Zhang Qian, the Yuezhi were defeated by the rising Xiongnu empire and fled westward, driving away the Sai (Scythians) from the Ili Valley in the Zhetysu and Dzungaria area. The Sai would subsequently migrate into South Asia, where they founded various Indo-Scythian kingdoms. After the Yuezhi retreat the Wusun subsequently settled the modern province of Gansu, in the valley of the Wushui-he (lit. "Raven Water-River"), as vassals of the Xiongnu. It is not clear whether the river was named after the tribe or vice versa.

Migration

to the Ili Valley :

The Wusun subsequently took over the Ili Valley, expanding over a large area and trying to keep away from the Xiongnu. According to Shiji, Wusun was a state located west of the Xiongnu. When the Xiongnu ruler died, Liejiaomi refused to serve the Xiongnu. The Xiongnu then sent a force to against the Wusun but were defeated, after which the Xiongnu even more than before considered Liejiaomi a supernatural being, avoiding conflict with him.

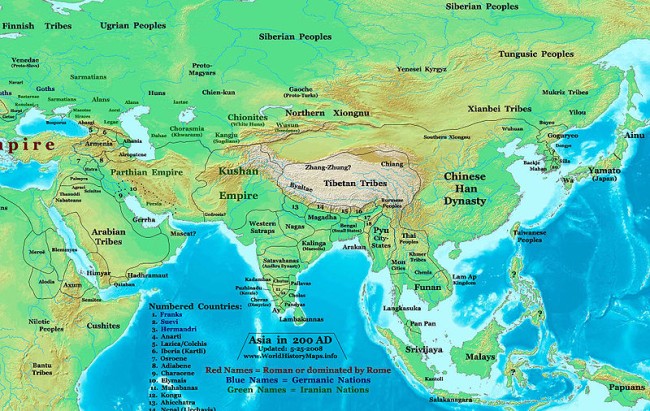

Wusun and their neighbours around 200 CE

Establishing relations with the Han :

In 125 BCE, under the Han Emperor Wu of Han (156-87 BCE), the Chinese traveller and diplomat Zhang Qian was sent to establish an alliance with the Wusun Against the Xiongnu. Qian estimated the Wusun to number 630,000, with 120,000 families and 188,000 men capable of bearing arms. Hanshu described them as occupying land that previously belonged to the Saka (Sai). To their north-west the Wusun bordered Kangju, located in modern Kazakhstan. To the west was Dayuan (Ferghana), and to the south were various city states. The Royal Court of the Wusun, the walled city of Chigu (Chinese: pinyin: chìgu; lit.: 'Red Valley'), was located in a side valley leading to Issyk Kul. Lying on one of the branches of the Silk Road Chigu was an important trading centre, but its exact location has not been established.

The Wusun approved of a possible alliance, and Zhang Qian was sent as ambassador in 115 BCE. According to the agreement the Wusun would jointly attack the Xiongnu with the Han, while they were offered a Han princess in marriage and the return of their original Gansu homeland (heqin). Due to fear of the Xiongnu, the Wusun however had second thoughts and suggested sending a delegation to the Han rather than moving their capital further west.

As

Han allies :

My family sent me off to be married on the other side of heaven. They sent me a long way to a strange land, to the king of Wusun. A domed lodging is my dwelling place with walls of felt. Meat is my food, with fermented milk as the sauce. I live with constant thoughts of my home, my heart is full of sorrow. I wish I were a golden swan, returning to my home country.

Xijun bore the Wusun a daughter but died soon afterward, at which point the Han court sent Princess Jieyou to succeed her. After the death of Cenzou, Jieyou married Wengguimi, Cenzou's cousin and successor. Jieyou lived for fifty years among the Wusun and bore five children, including the oldest Yuanguimi, whose half-brother Wujiutu was born to a Xiongnu mother. She sent numerous letters to the Han requesting assistance against the Xiongnu.

Around 80 BCE, the Wusun were attacked by the Xiongnu, who inflicted a devastating defeat upon them. In 72 BCE, the Kunmi of the Wusun requested assistance from the Han against the Xiongnu. The Han sent an army of 160,000 men, inflicting a crushing defeat upon the Xiongnu, capturing much booty and many slaves. In the campaign the Han captured the Tarim Basin city-state of Cheshi (Turpan), a previous ally of the Xiongnu, giving them direct contact with the Wusun. Afterwards the Wusun allied with the Dingling and Wuhuan to counter Xiongnu attacks. After their crushing victory against the Xiongnu the Wusun increased in strength, achieving significant influence over the city-states of the Tarim Basin. The son of the Kunmi became the ruler of Yarkand, while his daughter became the wife of the lord of Kucha. They came to play a role as a third force between the Han and the Xiongnu.

Around 64 BCE, according to Hanshu, Chinese agents were involved in a plot with a Wusun kunmi known as Wengguimi ("Fat King"), to kill a Wusun kunmi known to the Chinese as Nimi ("Mad King"). A Chinese deputy envoy called Chi Tu who brought a doctor to attend to Nimi was punished by castration when he returned to China.

In 64 BCE another Han princess was sent to Kunmi Wengguimi, but he died before her arrival. Han emperor Xuan then permitted the princess to return, since Jieyou had married the new Kunmi, Nimi, the son of Cenzou. Jieyou bore Nimi the son Chimi. Prince Wujiutu later killed Nimi, his half-brother. Fearing the wrath of the Han, Wujiutu adopted the title of Lesser Kunmi, while Yuanguimi was given the title Greater Kunmi. The Han accepted this system and bestowed both of them with the imperial seal. After both Yuanguimi and Chimi were dead, Jieyou asked Emperor Xuan for permission to return to China. She died in 49 BCE. Over the next decades the institution of Greater and Lesser Kunmi continued, with the Lesser Kunmi being married to a Xiongnu princess and the Greater Kunmi married to a Han princess.

In 5 BCE, during the reign of Uchjulü-Chanyu (8 BCE – CE 13), the Wusun attempted to raid Chuban pastures, but Uchjulü-Chanyu repulsed them, and the Wusun commander had to send his son to the Chuban court as a hostage. The forceful intervention of the Chinese usurper Wang Mang and internal strife brought disorder, and in 2 BCE one of the Wusun chieftains brought 80,000 Wusun to Kangju, asking for help against the Chinese. In a vain attempt to reconcile with China, he was duped and killed in 3 CE.

In 2 CE, Wang Mang issued a list of four regulations to the allied Xiongnu that the taking of any hostages from Chinese vassals, i.e. Wusun, Wuhuan and the statelets of the Western Regions, would not be tolerated.

In 74 CE the Wusun are recorded as having sent tribute to the Han military commanders in Cheshi. In 80 CE Ban Chao requested assistance from the Wusun against the city-state Quchi (Kucha) in the Tarim Basin. The Wusun were subsequently rewarded with silks, while diplomatic exchanges were resumed. During the 2nd century CE the Wusun continued their decline in political importance.

Later

history :

Physical

appearance :

Among the barbarians in the Western Regions, the look of the Wusun is the most unusual. The present barbarians who have green eyes and red hair, and look like macaque monkeys, are the offspring of this people.

Initially, when only a few number of skulls from Wusun territory were known, the Wusun were recognized as a Caucasoid people with slight Mongoloid admixture. Later, in a more thorough study by Soviet archaeologists of eighty-seven skulls of Zhetysu, the six skulls of the Wusun period were determined to be purely Caucasoid or close to it.

Language

:

The Sinologist Edwin G. Pulleyblank has suggested that the Wusun, along with the Yuezhi, the Dayuan, the Kangju and the people of Yanqi, could have been Tocharian-speaking. Colin Masica and David Keightley also suggest that the Wusun were Tocharian-speaking. Sinor finds it difficult to include the Wusun within the Tocharian category of Indo-European until further research. J. P. Mallory has suggested that the Wusun contained both Tocharian and Iranian elements. Central Asian scholar Christopher I. Beckwith suggests that the Wusun were Indo-Aryan-speaking. The first syllable of the Wusun royal title Kunmi was probably the royal title while the second syllable referred to the royal family name. Beckwith specifically suggests an Indo-Aryan etymology of the title Kunmi.

In the past, some scholars suggested that the Wusun spoke a Turkic language. Chinese scholar Han Rulin, as well as G. Vambery, A. Scherbak, P. Budberg, L. Bazin and V.P. Yudin, noted that the Wusun king's name Fu-li, as reported in Chinese sources and translated as 'wolf', resembles Proto-Turkic *borü 'wolf'. This suggestion however is rejected by Classical Chinese Literature expert Francis K. H. So, Professor at National Sun Yat-sen University. Other words listed by these scholars include the title bag, beg 'lord'. This theory has been criticized by modern Turkologists, including Peter B. Golden and Carter V. Findley, who explain that none of the mentioned words are actually Turkic in origin. Findley notes that the term böri is probably derived from one of the Iranian languages of Central Asia (cf. Khotanese birgga-). Meanwhile, Findley considers the title beg as certainly derived from the Sogdian baga 'lord', a cognate of Middle Persian bay (as used by the rulers of the Sassanid Empire), as well as Sanskrit bhaga and Russian bog. According to Encyclopædia Iranica: "The origin of beg is still disputed, though it is mostly agreed that it is a loan-word. Two principal etymologies have been proposed. The first etymology is from a Middle Iranian form of Old Iranian baga; though the meaning would fit since the Middle Persian forms of the word often mean 'lord,' used of the king or others. The second etymology is from Chinese (MC præk > bó) 'eldest (brother), (feudal) lord'. Gerhard Doerfer on the other hand seriously considers the possibility that the word is genuinely Turkish. Whatever the truth may be, there is no connection with Turkish berk, Mongolian berke 'strong' or Turkish bögü, Mongolian böge 'wizard, shaman.'"

Economy

:

The principal activity of the Wusun was cattle-raising, but they also practiced agriculture. Since the climate of Zhetysu and Dzungaria did not allow constant wandering, they probably wandered with each change of season in the search of pasture and water. Numerous archaeological finds have found querns and agricultural implements and bones of domesticated animals, suggesting a semi-nomadic pastoral economy.

Social

structure :

Wusun society seems to have been highly stratified. The main source of this stratification seems to have been property ownership. The wealthiest Wusuns are believed to have owned as many as 4,000 to 5,000 horses, and there is evidence pointing to privileged use of certain pastures. Typical of early patriarchal stratified societies, Wusun widows were obliged to remain within the family of their late husband by marrying one of his relatives, a concept known as levirate marriage. Y. A. Zadneprovskiy writes that the social inequality among the Wusun created social unrest among the lower strata. Wusun society also included many slaves, mostly prisoners of war. The Wusun are reported as having captured 10,000 slaves in a raid against the Xiongnu. Wusun slaves mainly laboured as servants and craftsmen, although the freemen formed the core of the Wusun economy.

Archaeology

:

A famous find is the Kargali burial of a female Shaman discovered at an altitude of 2,300 m, near Almaty, containing jewellery, clothing, head-dress and nearly 300 gold objects. A beautiful diadem of the Kargali burial attest to the artistic skill of these ancient jewellers. Another find at Tenlik in eastern Zhetysu contained the grave of a high-ranking warrior, whose clothing had been decorated with around 100 golden bosses.

Connection

to Western histography :

French historian Iaroslav Lebedynsky suggests that the Wusun may have been the Asii of Geographica.

Genetics

:

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

_Kazakhstan.jpg)