| XIONGNU

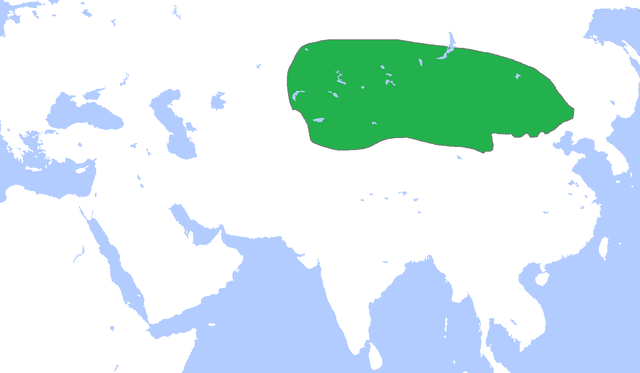

Before Han–Xiongnu War: Territory of the Xiongnu which includes Mongolia, East Kazakhstan, East Kyrgyzstan, and parts of northern China including Western Manchuria, Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, Gansu.

The Xiongnu (Chinese: Wade–Giles: Hsiung-nu) were a tribal confederation of nomadic peoples who, according to ancient Chinese sources, inhabited the eastern Eurasian Steppe from the 3rd century BC to the late 1st century AD. Chinese sources report that Modu Chanyu, the supreme leader after 209 BC, founded the Xiongnu Empire.

After their previous rivals, the Yuezhi, migrated into Central Asia during the 2nd century BC, the Xiongnu became a dominant power on the steppes of north-east Central Asia, centered on an area known later as Mongolia. The Xiongnu were also active in areas now part of Siberia, Inner Mongolia, Gansu and Xinjiang. Their relations with adjacent Chinese dynasties to the south-east were complex, with repeated periods of conflict and intrigue, alternating with exchanges of tribute, trade, and marriage treaties (heqin). During the Sixteen Kingdoms era, as one of the Five Barbarians, they founded several dynastic states in northern China, such as Former Zhao, Northern Liang and Xia.

Attempts to identify the Xiongnu with later groups of the western Eurasian Steppe remain controversial. Scythians and Sarmatians were concurrently to the west. The identity of the ethnic core of Xiongnu has been a subject of varied hypotheses, because only a few words, mainly titles and personal names, were preserved in the Chinese sources. The name Xiongnu may be cognate with that of the Huns or the Huna, although this is disputed. Other linguistic links – all of them also controversial – proposed by scholars include Iranian, Mongolic, Turkic, Uralic, Yeniseian, Tibeto-Burman or multi-ethnic.

History

:

Ancient China often came in contact with the Xianyun and the Xirong nomadic peoples. In later Chinese historiography, some groups of these peoples were believed to be the possible progenitors of the Xiongnu people. These nomadic people often had repeated military confrontations with the Shang and especially the Zhou, who often conquered and enslaved the nomads in an expansion drift. During the Warring States period, the armies from the Qin, Zhao, and Yan states were encroaching and conquering various nomadic territories that were inhabited by the Xiongnu and other Hu peoples.

Sinologist Edwin Pulleyblank argued that the Xiongnu were part of a Xirong group called Yiqu, who had lived in Shaanbei and had been influenced by China for centuries, before they were driven out by the Qin dynasty. Qin's campaign against the Xiongnu expanded Qin's territory at the expense of the Xiongnu. after the unification of Qin dynasty, Xiongnu was a threat to the northern board of Qin. They were like to attack Qin dynasty when they suffered natural disasters. In 215 BC, Qin Shi Huang sent General Meng Tian to conquer the Xiongnu and drive them from the Ordos Loop, which he did later that year. After the catastrophic defeat at the hands of Meng Tian, the Xiongnu leader Touman was forced to flee far into the Mongolian Plateau. The Qin empire became a threat to the Xiongnu, which ultimately led to the reorganization of the many tribes into a confederacy.

State formation :

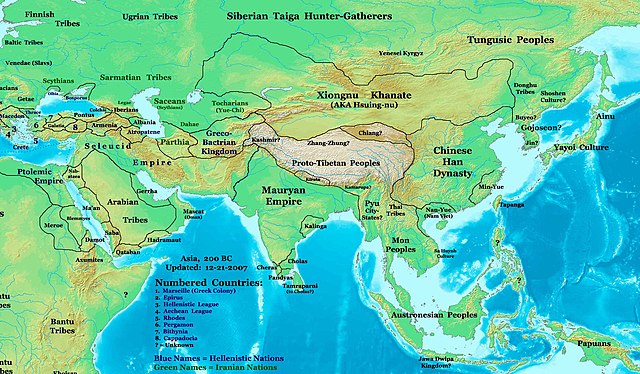

Domain and influence of Xiongnu under Modu Chanyu around 205 BC

Asia in 200 BC, showing the early Xiongnu state and its neighbors In 209 BC, three years before the founding of Han China, the Xiongnu were brought together in a powerful confederation under a new chanyu, Modu Chanyu. This new political unity transformed them into a more formidable state by enabling the formation of larger armies and the ability to exercise better strategic coordination. The Xiongnu adopted many of the Chinese agriculture techniques such as slaves for heavy labor, wore silk like the Chinese, and lived in Chinese-style homes. The reason for creating the confederation remains unclear. Suggestions include the need for a stronger state to deal with the Qin unification of China that resulted in a loss of the Ordos region at the hands of Meng Tian or the political crisis that overtook the Xiongnu in 215 BC when Qin armies evicted them from their pastures on the Yellow River.

After forging internal unity, Modu Chanyu expanded the empire on all sides. To the north he conquered a number of nomadic peoples, including the Dingling of southern Siberia. He crushed the power of the Donghu people of eastern Mongolia and Manchuria as well as the Yuezhi in the Hexi Corridor of Gansu, where his son, Jizhu, made a skull cup out of the Yuezhi king. Modu also reoccupied all the lands previously taken by the Qin general Meng Tian.

Under Modu's leadership, the Xiongnu threatened the Han dynasty, almost causing Emperor Gaozu, the first Han emperor, to lose his throne in 200 BC. By the time of Modu's death in 174 BC, the Xiongnu had driven the Yuezhi from the Hexi Corridor, killing the Yuezhi king in the process and asserting their presence in the Western Regions.

The Xiongnu were recognized as the most prominent of the nomads bordering the Chinese Han empire and during early relations between the Xiongnu and the Han, the former held the balance of power. According to the Book of Han, later quoted in Duan Chengshi's ninth century Miscellaneous Morsels from Youyang :

Also, according to the Han shu, Wang Wu and others were sent as envoys to pay a visit to the Xiongnu. According to the customs of the Xiongnu, if the Han envoys did not remove their tallies of authority, and if they did not allow their faces to be tattooed, they could not gain entrance into the yurts. Wang Wu and his company removed their tallies, submitted to tattoo, and thus gained entry. The Shanyu looked upon them very highly.

Xiongnu

hierarchy :

The ruler of the Xiongnu was called the Chanyu. Under him were the Tuqi Kings. The Tuqi King of the Left was normally the heir presumptive. Next lower in the hierarchy came more officials in pairs of left and right: the guli, the army commanders, the great governors, the danghu and the gudu. Beneath them came the commanders of detachments of one thousand, of one hundred, and of ten men. This nation of nomads, a people on the march, was organized like an army.

Yap, apparently describing the early period, places the Chanyu's main camp north of Shanxi with the Tuqi King of the Left holding the area north of Beijing and the Tuqi King of the Right holding the Ordos Loop area as far as Gansu. Grousset, probably describing the situation after the Xiongnu had been driven north, places the Chanyu on the upper Orkhon River near where Genghis Khan would later establish his capital of Karakorum. The Tuqi King of the Left lived in the east, probably on the high Kherlen River. The Tuqi King of the Right lived in the west, perhaps near present-day Uliastai in the Khangai Mountains.

Marriage diplomacy with Han China :

A Han Chinese glazed ceramic figurine of a mounted horse archer, 50 BC to 50 AD, late Western or early Eastern Han Dynasty In the winter of 200 BC, following a Xiongnu siege of Taiyuan, Emperor Gaozu of Han personally led a military campaign against Modu Chanyu. At the Battle of Baideng, he was ambushed reputedly by Xiongnu cavalry. The emperor was cut off from supplies and reinforcements for seven days, only narrowly escaping capture.

The Han sent princesses to marry Xiongnu leaders in their efforts to stop the border raids. Along with arranged marriages, the Han sent gifts to bribe the Xiongnu to stop attacking. After the defeat at Pingcheng in 200 BC, the Han emperor abandoned a military solution to the Xiongnu threat. Instead, in 198 BC , the courtier Liu Jing [zh] was dispatched for negotiations. The peace settlement eventually reached between the parties included a Han princess given in marriage to the chanyu (called heqin) (Chinese: lit.: 'harmonious kinship'); periodic gifts to the Xiongnu of silk, distilled beverages and rice; equal status between the states; and the Great Wall as mutual border.

This first treaty set the pattern for relations between the Han and the Xiongnu for sixty years. Up to 135 BC, the treaty was renewed nine times, each time with an increase in the "gifts" to the Xiongnu Empire. In 192 BC, Modun even asked for the hand of Emperor Gaozu of Han widow Empress Lü Zhi. His son and successor, the energetic Jiyu, known as the Laoshang Chanyu, continued his father's expansionist policies. Laoshang succeeded in negotiating with Emperor Wen terms for the maintenance of a large scale government sponsored market system.

While the Xiongnu benefited handsomely, from the Chinese perspective marriage treaties were costly, very humiliating, and ineffective. Laoshang Chanyu showed that he did not take the peace treaty seriously. On one occasion his scouts penetrated to a point near Chang'an. In 166 BC he personally led 140,000 cavalry to invade Anding, reaching as far as the imperial retreat at Yong. In 158 BC, his successor sent 30,000 cavalry to attack Shangdang and another 30,000 to Yunzhong.[citation needed]

The Xiongnu also practiced marriage alliances with Han dynasty officers and officials who defected to their side. The older sister of the Chanyu (the Xiongnu ruler) was married to the Xiongnu General Zhao Xin, the Marquis of Xi who was serving the Han dynasty. The daughter of the Chanyu was married to the Han Chinese General Li Ling after he surrendered and defected. Another Han Chinese General who defected to the Xiongnu was Li Guangli, general in the War of the Heavenly Horses, who also married a daughter of the Chanyu.

When the Eastern Jin dynasty ended the Xianbei Northern Wei received the Han Chinese Jin prince Sima Chuzhi as a refugee. A Northern Wei Xianbei Princess married Sima Chuzhi, giving birth to Sima Jinlong. Northern Liang Xiongnu King Juqu Mujian's daughter married Sima Jinlong.

Han-Xiongnu war :

The Han dynasty made preparations for war when the Han Emperor Wu dispatched the explorer Zhang Qian to explore the mysterious kingdoms to the west and to form an alliance with the Yuezhi people in order to combat the Xiongnu. During this time Zhang married a Xiongnu wife, who bore him a son, and gained the trust of the Xiongnu leader. While Zhang Qian did not succeed in this mission, his reports of the west provided even greater incentive to counter the Xiongnu hold on westward routes out of China, and the Chinese prepared to mount a large scale attack using the Northern Silk Road to move men and material.

While Han China was making preparations for a military confrontation since the reign of Emperor Wen, the break did not come until 133 BC, following an abortive trap to ambush the chanyu at Mayi. By that point the empire was consolidated politically, militarily and economically, and was led by an adventurous pro-war faction at court. In that year, Emperor Wu reversed the decision he had made the year before to renew the peace treaty.

Full-scale war broke out in autumn 129 BC, when 40,000 Chinese cavalry made a surprise attack on the Xiongnu at the border markets. In 127 BC, the Han general Wei Qing retook the Ordos. In 121 BC, the Xiongnu suffered another setback when Huo Qubing led a force of light cavalry westward out of Longxi and within six days fought his way through five Xiongnu kingdoms. The Xiongnu Hunye king was forced to surrender with 40,000 men. In 119 BC both Huo and Wei, each leading 50,000 cavalrymen and 100,000 footsoldiers (in order to keep up with the mobility of the Xiongnu, many of the non-cavalry Han soldiers were mobile infantrymen who traveled on horseback but fought on foot), and advancing along different routes, forced the chanyu and his Xiongnu court to flee north of the Gobi Desert. [page needed] Major logistical difficulties limited the duration and long-term continuation of these campaigns. According to the analysis of Yan You, the difficulties were twofold. Firstly there was the problem of supplying food across long distances. Secondly, the weather in the northern Xiongnu lands was difficult for Han soldiers, who could never carry enough fuel. According to official reports, the Xiongnu lost 80,000 to 90,000 men, and out of the 140,000 horses the Han forces had brought into the desert, fewer than 30,000 returned to China.

In 104 and 102 BC, the Han fought and won the War of the Heavenly Horses against the Kingdom of Dayuan. As a result, the Han gained many Ferghana horses which further aided them in their battle against the Xiongnu. As a result of these battles, the Chinese controlled the strategic region from the Ordos and Gansu corridor to Lop Nor. They succeeded in separating the Xiongnu from the Qiang peoples to the south, and also gained direct access to the Western Regions. Because of strong Chinese control over the Xiongnu, the Xiongnu became unstable and were no longer a threat to the Han Chinese.

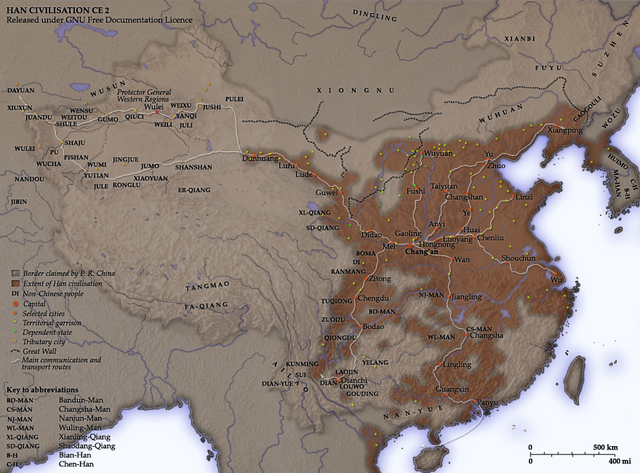

Xiongnu among other people in Asia around 1 AD Ban Chao, Protector General (Duhu) of the Han dynasty, embarked with an army of 70,000 soldiers in a campaign against the Xiongnu remnants who were harassing the trade route now known as the Silk Road. His successful military campaign saw the subjugation of one Xiongnu tribe after another. Ban Chao also sent an envoy named Gan Ying to Daqin (Rome). Ban Chao was created the Marquess of Dingyuan (i.e., "the Marquess who stabilized faraway places") for his services to the Han Empire and returned to the capital Luoyang at the age of 70 years and died there in the year 102. Following his death, the power of the Xiongnu in the Western Regions increased again, and the emperors of subsequent dynasties did not reach as far west until the Tang dynasty.

Xiongnu

Civil War (60–53 BC) :

Tributary relations with the Han :

Bronze seal says "To Han obedient, friendly and loyal chief of Xiongnu of Han".Bronze seal conferred by the Eastern Han government on a Xiongnu chief In 53 BC Huhanye decided to enter into tributary relations with Han China. The original terms insisted on by the Han court were that, first, the Chanyu or his representatives should come to the capital to pay homage; secondly, the Chanyu should send a hostage prince; and thirdly, the Chanyu should present tribute to the Han emperor. The political status of the Xiongnu in the Chinese world order was reduced from that of a "brotherly state" to that of an "outer vassal". During this period, however, the Xiongnu maintained political sovereignty and full territorial integrity. The Great Wall of China continued to serve as the line of demarcation between Han and Xiongnu.[citation needed]

Huhanye sent his son, the "wise king of the right" Shuloujutang, to the Han court as hostage. In 51 BC he personally visited Chang'an to pay homage to the emperor on the Lunar New Year. In the same year, another envoy Qijushan was received at the Ganquan Palace in the north-west of modern Shanxi. On the financial side, Huhanye was amply rewarded in large quantities of gold, cash, clothes, silk, horses and grain for his participation. Huhanye made two further homage trips, in 49 BC and 33 BC; with each one the imperial gifts were increased. On the last trip, Huhanye took the opportunity to ask to be allowed to become an imperial son-in-law. As a sign of the decline in the political status of the Xiongnu, Emperor Yuan refused, giving him instead five ladies-in-waiting. One of them was Wang Zhaojun, famed in Chinese folklore as one of the Four Beauties.

When Zhizhi learned of his brother's submission, he also sent a son to the Han court as hostage in 53 BC. Then twice, in 51 BC and 50 BC, he sent envoys to the Han court with tribute. But having failed to pay homage personally, he was never admitted to the tributary system. In 36 BC, a junior officer named Chen Tang, with the help of Gan Yanshou, protector-general of the Western Regions, assembled an expeditionary force that defeated him at the Battle of Zhizhi and sent his head as a trophy to Chang'an.

Tributary relations were discontinued during the reign of Huduershi (18 AD–48), corresponding to the political upheavals of the Xin Dynasty in China. The Xiongnu took the opportunity to regain control of the western regions, as well as neighboring peoples such as the Wuhuan. In 24 AD, Hudershi even talked about reversing the tributary system.

Southern Xiongnu and Northern Xiongnu :

An Eastern Han Chinese glazed ceramic statue of a horse with bridle and halter headgear, from Sichuan, late 2nd century to early 3rd century AD The Xiongnu's new power was met with a policy of appeasement by Emperor Guangwu. At the height of his power, Huduershi even compared himself to his illustrious ancestor, Modu. Due to growing regionalism among the Xiongnu, however, Huduershi was never able to establish unquestioned authority. In contravention of a principle of fraternal succession established by Huhanye, Huduershi designated his son Punu as heir-apparent. However, as the eldest son of the preceding chanyu, Bi (Pi) – the Rizhu King of the Right – had a more legitimate claim. Consequently, Bi refused to attend the annual meeting at the chanyu's court. Nevertheless, in 46 AD, Punu ascended the throne.

In 48 AD, a confederation of eight Xiongnu tribes in Bi's power base in the south, with a military force totalling 40,000 to 50,000 men, seceded from Punu's kingdom and acclaimed Bi as chanyu. This kingdom became known as the Southern Xiongnu.

The

Northern Xiongnu :

In 49 AD, Tsi Yung, a Han governor of Liaodong, allied with the Wuhuan and Xianbei, attacked the Northern Xiongnu. The Northern Xiongnu suffered two major defeats: one at the hands of the Xianbei in 85 AD, and by the Han during the Battle of Ikh Bayan, in 89 AD. The northern chanyu fled to the north-west with his subjects.

In about 155 AD, the Northern Xiongnu were decisively "crushed and subjugated" by the Xianbei.

According to the 5th century Book of Wei, the remnants of Northern Chanyu's tribe settled as Yueban, near Kucha and subjugated the Wusun; while the rest fled across the Altai mountains towards Kangju in Transoxania. It states that this group later became the Hephthalites.

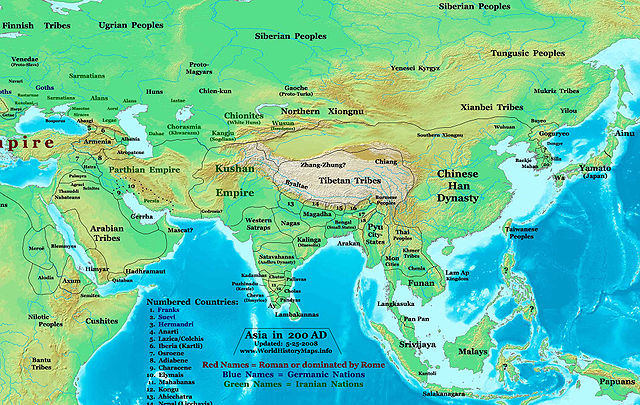

Southern and Northern Xiongnu in 200 AD, before the collapse of the Han Dynasty

The Southern Xiongnu :

Tensions were evident between Han settlers and practitioners of the nomadic way of life. Thus, in 94, Anguo Chanyu joined forces with newly subjugated Xiongnu from the north and started a large scale rebellion against the Han.

During the late 2nd century AD, the southern Xiongnu were drawn into the rebellions then plaguing the Han court. In 188, the chanyu was murdered by some of his own subjects for agreeing to send troops to help the Han suppress a rebellion in Hebei – many of the Xiongnu feared that it would set a precedent for unending military service to the Han court. The murdered chanyu's son Yufuluo, entitled Chizhisizhu, succeeded him, but was then overthrown by the same rebellious faction in 189. He travelled to Luoyang (the Han capital) to seek aid from the Han court, but at this time the Han court was in disorder from the clash between Grand General He Jin and the eunuchs, and the intervention of the warlord Dong Zhuo. The chanyu had no choice but to settle down with his followers in Pingyang, a city in Shanxi. In 195, he died and was succeeded as chanyu by his brother Huchuquan Chanyu.

In 215–216 AD, the warlord-statesman Cao Cao detained Huchuquan Chanyu in the city of Ye, and divided his followers in Shanxi into five divisions: left, right, south, north, and centre. This was aimed at preventing the exiled Xiongnu in Shanxi from engaging in rebellion, and also allowed Cao Cao to use the Xiongnu as auxiliaries in his cavalry.

Later the Xiongnu aristocracy in Shanxi changed their surname from Luanti to Liu for prestige reasons, claiming that they were related to the Han imperial clan through the old intermarriage policy. After Huchuquan, the Southern Xiongnu were partitioned into five local tribes. Each local chief was under the "surveillance of a chinese resident", while the shanyu was in "semicaptivity at the imperial court."

Later

Xiongnu states in northern China :

Fang Xuanling's Book of Jin lists nineteen Xiongnu tribes: Tuge, Xianzhi, Koutou, Wutan, Chile, Hanzhi, Heilang, Chisha, Yugang, Weisuo, Tutong, BOmie, Qiangqu, Helai, Zhongqin, Dalou, Yongqu, Zhenshu, and Lijie.

Former

Zhao state (304 – 329) :

In 316, the Emperor Min of Jin China was captured in Chang'an. Both emperors were humiliated as cupbearers in Linfen before being executed in 313 and 318

North China came under Xiongnu rule while the remnants of the Jin dynasty survived in the south at Jiankang.

The

reign of Liu Yao (318 – 329) :

However, the eastern part of north China came under the control of a rebel Xiongnu-Han general of Jie ancestry named Shi Le. Liu Yao and Shi Le fought a long war until 329, when Liu Yao was captured in battle and executed. Chang'an fell to Shi Le soon after, and the Xiongnu dynasty was wiped out. North China was ruled by Shi Le's Later Zhao dynasty for the next 20 years.

However, the "Liu" Xiongnu remained active in the north for at least another century.

Tiefu

and Xia (260 – 431) :

Tongwancheng (meaning "Unite All Nations") was the capital of the Xia (Sixteen Kingdoms), whose rulers claimed descent from Modu Chanyu.

The ruined city was discovered in 1996 and the State Council designated it as a cultural relic under top state protection. The repair of the Yong'an Platform, where Helian Bobo, emperor of the Da Xia regime, reviewed parading troops, has been finished and restoration on the 31-meter-tall turret follows.[page needed]

Juqu

and Northern Liang (401 – 460) :

Significance

:

Ethnolinguistic origins :

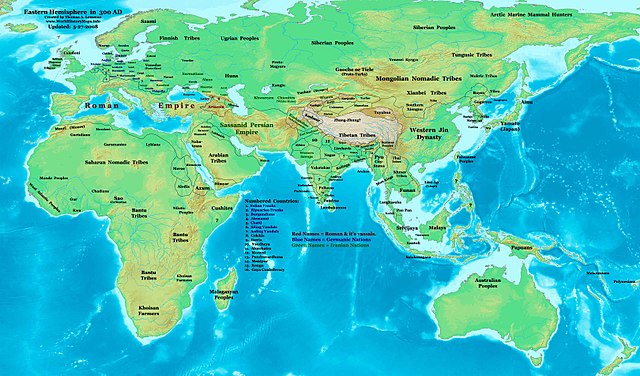

Location of Xiongnu and other steppe nations in 300 AD The Chinese name for the Xiongnu was a pejorative term in itself, as the characters have the meaning of "fierce slave". (The Chinese characters are pronounced as Xiongnú in modern Mandarin Chinese.)

There are several theories on the ethnolinguistic identity of the Xiongnu.

Huns

:

The Xiongnu-Hun hypothesis originated with the 18th-century French historian Joseph de Guignes, who noticed that ancient Chinese scholars had referred to members of tribes associated with the Xiongnu by names similar to "Hun", albeit with varying Chinese characters. Étienne de la Vaissière has shown that, in the Sogdian script used in the so-called "Sogdian Ancient Letters", both the Xiongnu and Huns were referred to as ywn (xwn), indicating that the two were synonymous. Although the theory that the Xiongnu were precursors of the Huns known later in Europe is now accepted by many scholars, it has yet to become a consensus view. The identification with the Huns may be either incorrect or an oversimplification (as would appear to be the case with a proto-Mongol people, the Rouran, who have sometimes been linked to the Avars of Central Europe).

Iranian theories :

Harold Walter Bailey proposed an Iranian origin of the Xiongnu, recognizing all the earliest Xiongnu names of the 2nd century BC as being of the Iranian type. This theory is supported by turkologist Henryk Jankowski. Central Asian scholar Christopher I. Beckwith notes that the Xiongnu name could be a cognate of Scythian, Saka and Sogdia, corresponding to a name for Northern Iranians. According to Beckwith the Xiongnu could have contained a leading Iranian component when they started out, but more likely they had earlier been subjects of an Iranian people and learned from them the Iranian nomadic model.

In the 1994 UNESCO-published History of Civilizations of Central Asia, its editor János Harmatta claims that the royal tribes and kings of the Xiongnu bore Iranian names, that all Xiongnu words noted by the Chinese can be explained from a Scythian language, and that it is therefore clear that the majority of Xiongnu tribes spoke an Eastern Iranian language.

Mongolic

theories :

Genghis Khan refers to the time of Modu Chanyu as "the remote times of our Chanyu" in his letter to Daoist Qiu Chuji. Sun and moon symbol of Xiongnu that discovered by archaeologists is similar to Mongolian Soyombo symbol.

Turkic

theories :

Chinese sources link the Tiele people and Ashina to the Xiongnu, According to the Book of Zhou and the History of the Northern Dynasties, the Ashina clan was a component of the Xiongnu confederation.

Uyghur Khagans claimed descent from the Xiongnu (according to Chinese history Weishu, the founder of the Uyghur Khaganate was descended from a Xiongnu ruler).

Both the 7th-century Chinese History of the Northern Dynasties and the Book of Zhou, an inscription in the Sogdian language, report the Göktürks to be a subgroup of the Xiongnu.

Yeniseian

theories :

According to Vovin (2007) the Xiongnu likely spoke a Yeniseian language. They were possibly a southern Yeniseian branch.

Multiple

ethnicities :

Chinese sources link the Tiele people and Ashina to the Xiongnu, not all Turkic peoples. According to the Book of Zhou and the History of the Northern Dynasties, the Ashina clan was a component of the Xiongnu confederation, but this connection is disputed, and according to the Book of Sui and the Tongdian, they were "mixed nomads" (simplified Chinese: pinyin: zá hú) from Pingliang. The Ashina and Tiele may have been separate ethnic groups who mixed with the Xiongnu. Indeed, Chinese sources link many nomadic peoples (hu; see Wu Hu) on their northern borders to the Xiongnu, just as Greco-Roman historiographers called Avars and Huns "Scythians". The Greek cognate of Tourkia was used by the Byzantine emperor and scholar Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus in his book De Administrando Imperio, though in his use, "Turks" always referred to Magyars. Such archaizing was a common literary topos, and implied similar geographic origins and nomadic lifestyle but not direct filiation.

Some Uyghurs claimed descent from the Xiongnu (according to Chinese history Weishu, the founder of the Uyghur Khaganate was descended from a Xiongnu ruler), but many contemporary scholars do not consider the modern Uyghurs to be of direct linear descent from the old Uyghur Khaganate because modern Uyghur language and Old Uyghur languages are different. Rather, they consider them to be descendants of a number of people, one of them the ancient Uyghurs.

In various kinds of ancient inscriptions on monuments of Munmu of Silla, it is recorded that King Munmu had Xiongnu ancestry. According to several historians, it is possible that there were tribes of Koreanic origin. There are also some Korean researchers that point out that the grave goods of Silla and of the eastern Xiongnu are alike.

Language

isolate theories :

Geographic origins :

Bronze plaque of a man of the Ordos Plateau, long held by the Xiongnu. British Museum. Otto Maenchen-Helfen notes that the statuette displays Caucasoid features The original geographic location of the Xiongnu is disputed among steppe archaeologists. Since the 1960s, the geographic origin of the Xiongnu has attempted to be traced through an analysis of Early Iron Age burial constructions. No region has been proven to have mortuary practices that clearly match those of the Xiongnu.

Archaeology

:

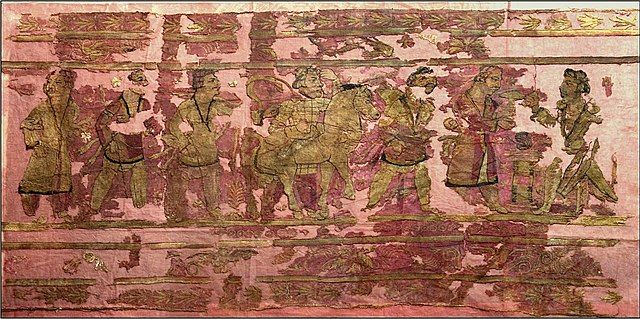

Portraits found in the Noin-Ula excavations demonstrate other cultural evidences and influences, showing that Chinese and Xiongnu art have influenced each other mutually. Some of these embroidered portraits in the Noin-Ula kurgans also depict the Xiongnu with long braided hair with wide ribbons, which is seen to be identical with the Ashina clan hair-style. Well-preserved bodies in Xiongnu and pre-Xiongnu tombs in the Mongolian Republic and southern Siberia show both Mongoloid and Caucasian features.

Analysis of skeletal remains from some sites attributed to the Xiongnu provides an identification of dolichocephalic Mongoloid, ethnically distinct from neighboring populations in present-day Mongolia. Russian and Chinese anthropological and craniofacial studies show that the Xiongnu were physically very heterogenous, with six different population clusters showing different degrees of Mongoloid and Caucasoid physical traits.

Xiongnu bow Presently, there exist four fully excavated and well documented cemeteries: Ivolga, Dyrestui, Burkhan Tolgoi, and Daodunzi. Additionally thousands of tombs have been recorded in Transbaikalia and Mongolia. The Tamir 1 excavation site from a 2005 Silkroad Arkanghai Excavation Project is the only Xiongnu cemetery in Mongolia to be fully mapped in scale. Tamir 1 was located on Tamiryn Ulaan Khoshuu, a prominent granitic outcrop near other cemeteries of the Neolithic, Bronze Age, and Mongol periods. Important finds at the site included a lacquer bowl, glass beads, and three TLV mirrors. Archaeologists from this project believe that these artifacts paired with the general richness and size of the graves suggests that this cemetery was for more important or wealthy Xiongnu individuals.

The TLV mirrors are of particular interest. Three mirrors were acquired from three different graves at the site. The mirror found at feature 160 is believed to be a low-quality, local imitation of a Han mirror, while the whole mirror found at feature 100 and fragments of a mirror found at feature 109 are believed to belong to the classical TLV mirrors and date back to the Xin Dynasty or the early to middle Eastern Han period. The archaeologists have chosen to, for the most part, refrain from positing anything about Han-Xiongnu relations based on these particular mirrors. However, they were willing to mention the following :

"There is no clear indication of the ethnicity of this tomb occupant, but in a similar brick-chambered tomb of the late Eastern Han period at the same cemetery, archaeologists discovered a bronze seal with the official title that the Han government bestowed upon the leader of the Xiongnu. The excavators suggested that these brick chamber tombs all belong to the Xiongnu (Qinghai 1993)."

Classifications of these burial sites make distinction between two prevailing type of burials: "(1) monumental ramped terrace tombs which are often flanked by smaller "satellite" burials and (2) 'circular' or 'ring' burials."Some scholars consider this a division between "elite" graves and "commoner" graves. Other scholars, find this division too simplistic and not evocative of a true distinction because it shows "ignorance of the nature of the mortuary investments and typically luxuriant burial assemblages [and does not account for] the discovery of other lesser interments that do not qualify as either of these types."

Genetics

:

A genetic study published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology in July 2010 analyzed three individuals buried at an elite Xiongnu cemetery in Duurlig Nars of Northeast Mongolia around 0 AD. One male carried the paternal haplogroup C3 and the maternal haplogroup D4. The female also carried the maternal haplogroup D4. The third individual, a male, carried the paternal haplogroup R1a1 and the maternal haplogroup U2e1. C3 and D4 are both common in Northeast Asia, while R1a1 and U2e1 are both West Eurasian lineages, with R1a1 being particularly associated with eastward migrations of Indo-European peoples.

A genetic study published in Nature in May 2018 examined the remains of five Xiongnu. The four samples of Y-DNA extracted belonged to haplogroups R1, R1b, O3a and O3a3b2, while the five samples of mtDNA extracted belonged to haplogroups D4b2b4, N9a2a, G3a3, D4a6 and D4b2b2b. The examined Xiongnu were found to be of mixed East Asian and West Eurasian origin, and to have had a larger amount of East Asian ancestry than neighboring Sakas, Wusun and Kangju. The evidence suggested that the Huns emerged through westward migrations of Xiongnu and subsequent admixture between them and Sakas.

A genetic study published in Scientific Reports in November 2019 examined the remains of three individuals buried at Hunnic cemeteries in the Carpathian Basin in the 5th century AD. The results from the study supported the theory that the Huns were descended from the Xiongnu.

A genetic study published in Human Genetics in July 2020 which examined the remains of 52 individuals excavated from the Tamir Ulaan Khoshuu cemetery in Mongolia propose the ancestors of the Xiongnu as an admixture between Scythians and Siberians and support the idea that the Huns are their descendants.

Culture

:

Gold stag with eagle's head, and ten further heads in the antlers.

An object inspired by the art of the Siberian Altai mountain, possibly

Pazyryk, unearthed at the site of Nalinggaotu, Shenmu County, near

Xi'an, China.Possibly from the "Hun people who lived in the

prairie in Northern China". Dated to the 4th-3rd century BC,

or Han Dynasty period. Shaanxi History Museum.

Xiongnu art is harder to distinguish from Saka or Scythian art. There was a similarity present in stylistic execution, but Xiongnu art and Saka art did often differ in terms of iconography. Saka art does not appear to have included predation scenes, especially with dead prey, or same-animal combat. Additionally, Saka art included elements not common to Xiongnu iconography, such as a winged, horned horse. The two cultures also used two different bird heads. Xiongnu depictions of birds have a tendency to have a moderate eye and beak and have ears, while Saka birds have a pronounced eye and beak and no ears. Some scholars [who?] claim these differences are indicative of cultural differences. Scholar Sophia-Karin Psarras claims that Xiongnu images of animal predation, specifically tiger plus prey, is spiritual, representative of death and rebirth, and same-animal combat is representative of the acquisition of or maintenance of power.

Rock

art and writing :

Excavations conducted between 1924 and 1925 in the Noin-Ula kurgans produced objects with over twenty carved characters, which were either identical or very similar to that of to the runic letters of the Old Turkic alphabet discovered in the Orkhon Valley. From this a some scholars hold that the Xiongnu had a script similar to Eurasian runiform and this alphabet itself served as the basis for the ancient Turkic writing.

The Records of the Grand Historian (vol. 110) state that when the Xiongnu noted down something or transmitted a message, they made cuts on a piece of wood; they also mention a "Hu script".

2nd century BCE – 2nd century CE characters of Hun-Xianbei script (Mongolia and Inner Mongolia), N. Ishjamts, "Nomads In Eastern Central Asia", in the History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume 2, Fig 5, p. 166, UNESCO Publishing, 1996, ISBN 92-3-102846-4.

2nd century BCE – 2nd century CE, characters of Hun-Xianbei script (Mongolia and Inner Mongolia), N. Ishjamts, "Nomads In Eastern Central Asia", in the History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume 2, Fig 5, p. 166, UNESCO Publishing, 1996, ISBN 92-3-102846-4.

Diet

:

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |