| ZOROASTRIANISM

The Faravahar, a symbol commonly used to signify Zoroastrianism Zoroastrianism or Mazdayasna is one of the world's oldest continuously practiced religions. It is a multi-faceted faith centered on a dualistic cosmology of good and evil and an eschatology predicting the ultimate conquest of evil with theological elements of henotheism, monotheism/monism, and polytheism. Ascribed to the teachings of the Iranian-speaking spiritual leader Zoroaster (also known as Zarathustra), it exalts an uncreated and benevolent deity of wisdom, Ahura Mazda (Wise Lord), as its supreme being. Historical features of Zoroastrianism, such as messianism, judgment after death, heaven and hell, and free will may have influenced other religious and philosophical systems, including Second Temple Judaism, Gnosticism, Greek philosophy, Christianity, Islam, the Bahá'í Faith, and Buddhism.

With possible roots dating back to the second millennium BCE, Zoroastrianism enters recorded history in the 5th century BCE. It served as the state religion of the ancient Iranian empires for more than a millennium, from around 600 BCE to 650 CE, but declined from the 7th century onwards following the Muslim conquest of Persia of 633–654. Recent estimates place the current number of Zoroastrians at around 110,000–120,000 at most with the majority living in India, Iran, and North America; their number has been thought to be declining.

The most important texts of the religion are those of the Avesta, which includes as central the writings of Zoroaster known as the Gathas, enigmatic ritual poems that define the religion's precepts, which is within Yasna, the main worship service of modern Zoroastrianism. The religious philosophy of Zoroaster divided the early Iranian gods of the Proto-Indo-Iranian tradition into ahuras and daevas, the latter of which were not considered worthy of worship. Zoroaster proclaimed that Ahura Mazda was the supreme creator, the creative and sustaining force of the universe through Asha, and that human beings are given a right of choice between supporting Ahura Mazda or not, making them responsible for their choices. Though Ahura Mazda has no equal contesting force, Angra Mainyu (destructive spirit/mentality), whose forces are born from Aka Manah (evil thought), is considered the main adversarial force of the religion, standing against Spenta Mainyu (creative spirit/mentality). Middle Persian literature developed Angra Mainyu further into Ahriman and advancing him to be the direct adversary to Ahura Mazda.

In Zoroastrianism, Asha (truth, cosmic order), the life force that originates from Ahura Mazda, stands in opposition to Druj (falsehood, deceit) and Ahura Mazda is considered to be all-good with no evil emanating from the deity. Ahura Mazda works in getig (the visible material realm) and menog (the invisible spiritual and mental realm) through the seven (six when excluding Spenta Mainyu) Amesha Spentas (the direct emanations of Ahura Mazda) and the host of other Yazatas (literally meaning "worthy of worship"), who all worship Ahura Mazda in the Avesta and other texts and who Ahura Mazda requests worship towards in the same texts.

Zoroastrianism is not uniform in theological and philosophical thought, especially with historical and modern influences having a significant impact on individual and local beliefs, practices, values and vocabulary, sometimes merging with tradition and in other cases displacing it. Modern Zoroastrianism, however, tends to divide itself into either Reformist or Traditionalist camps with various smaller movements arising. In Zoroastrianism, the purpose in life is to become an Ashavan (a master of Asha) and to bring happiness into the world, which contributes to the cosmic battle against evil. Zoroastrianism's core teachings include :

•

Follow the Threefold

Path of Asha: Humata, Huxta, Huvarshta (Good Thoughts, Good Words,

Good Deeds).

Terminology

:

The first surviving reference to Zoroaster in English scholarship is attributed to Thomas Browne (1605–1682), who briefly refers to Zoroaster in his 1643 Religio Medici. The term Mazdaism is an alternative form in English used as well for the faith, taking Mazda- from the name Ahura Mazda and adding the suffix -ism to suggest a belief system.

Overview

:

Scholars and theologians have long debated on the nature of Zoroastrianism, with dualism, monotheism, and polytheism being the main terms applied to the religion. Some scholars assert that Zoroastrianism's concept of divinity covers both being and mind as immanent entities, describing Zoroastrianism as having a belief in an immanent self-creating universe with consciousness as its special attribute, thereby putting Zoroastrianism in the pantheistic fold sharing its origin with Indian Brahmanism. In any case, Asha, the main spiritual force which comes from Ahura Mazda, is the cosmic order which is the antithesis of chaos, which is evident as druj, falsehood and disorder. The resulting cosmic conflict involves all of creation, mental/spiritual and material, including humanity at its core, which has an active role to play in the conflict.

In the Zoroastrian tradition, druj comes from Angra Mainyu (also referred to in later texts as "Ahriman"), the destructive spirit/mentality, while the main representative of Asha in this conflict is Spenta Mainyu, the creative spirit/mentality. Ahura Mazda is immanent in humankind and interacts with creation through emanations known as the Amesha Spenta, the bounteous/holy immortals, which are representative and guardians of different aspects of creation and the ideal personality. Ahura Mazda, through these Amesha Spenta, is assisted by a league of countless divinities called Yazatas, meaning "worthy of worship", and each is generally a hypostasis of a moral or physical aspect of creation. According to Zoroastrian cosmology, in articulating the Ahuna Vairya formula, Ahura Mazda made the ultimate triumph of good against Angra Mainyu evident. Ahura Mazda will ultimately prevail over the evil Angra Mainyu, at which point reality will undergo a cosmic renovation called Frashokereti and limited time will end. In the final renovation, all of creation—even the souls of the dead that were initially banished to or chose to descend into "darkness"—will be reunited with Ahura Mazda in the Kshatra Vairya (meaning "best dominion"), being resurrected to immortality. In Middle Persian literature, the prominent belief was that at the end of time a savior-figure known as the Saoshyant would bring about the Frashokereti, while in the Gathic texts the term Saoshyant (meaning "one who brings benefit") referred to all believers of Mazdayasna but changed into a messianic concept in later writings.

Zoroastrian theology includes foremost the importance of following the Threefold Path of Asha revolving around Good Thoughts, Good Words, and Good Deeds. There is also a heavy emphasis on spreading happiness, mostly through charity, and respecting the spiritual equality and duty of the genders. Zoroastrianism's emphasis on the protection and veneration of nature and its elements has led some to proclaim it as the "world's first proponent of ecology." The Avesta and other texts call for the protection of water, earth, fire and air making it, in effect, an ecological religion: "It is not surprising that Mazdaism…is called the first ecological religion. The reverence for Yazatas (divine spirits) emphasizes the preservation of nature (Avesta: Yasnas 1.19, 3.4, 16.9; Yashts 6.3–4, 10.13)." However, this particular assertion is undermined by the fact that early Zoroastrians had a duty to exterminate "evil" species, a dictate no longer followed in modern Zoroastrianism.

Practices :

An

8th century Tang dynasty Chinese clay figurine of a Sogdian man

wearing a distinctive cap and face veil, possibly a camel rider

or even a Zoroastrian priest engaging in a ritual at a fire temple,

since face veils were used to avoid contaminating the holy fire

with breath or saliva; Museum of Oriental Art (Turin), Italy.

In Zoroastrian tradition, life is a temporary state in which a mortal is expected to actively participate in the continuing battle between Asha and Druj. Prior to being born, the urvan (soul) of an individual is still united with its fravashi (personal/higher spirit), which has existed since Ahura Mazda created the universe. The fravashi before the urvan's split act as aids in the maintenance of creation with Ahura Mazda. During life, the fravashi act as aspirational concepts, spiritual protectors, and the fravashi of bloodline, cultural, and spiritual ancestors and heroes are venerated and can be called upon for aid. On the fourth day after death, the urvan is reunited with its fravashi, in which the experiences of life in the material world are collected for the continuing battle in the spiritual world. For the most part, Zoroastrianism does not have a notion of reincarnation, at least not until the Frashokereti. Followers of Ilm-e-Kshnoom in India believe in reincarnation and practice vegetarianism, among other currently non-traditional opinions, although there have been various theological statements supporting vegetarianism in Zoroastrianism's history and claims that Zoroaster was vegetarian.

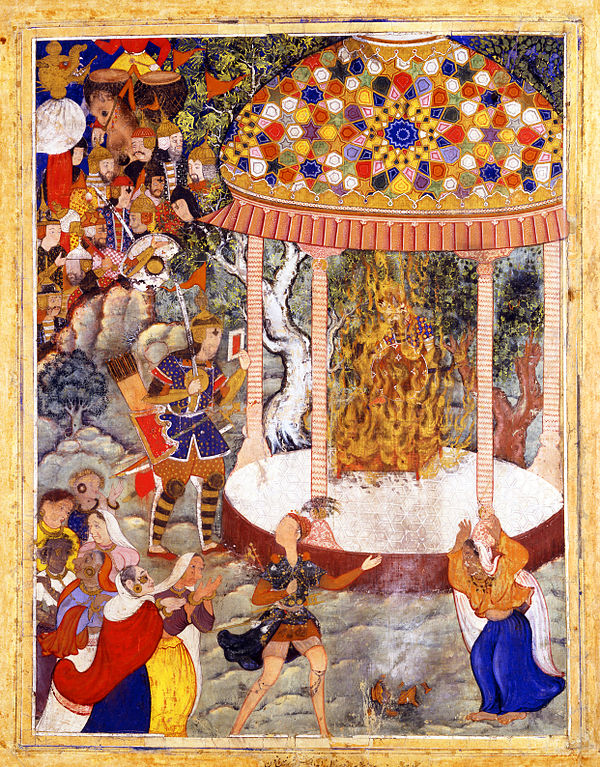

In Zoroastrianism, water (aban) and fire (atar) are agents of ritual purity, and the associated purification ceremonies are considered the basis of ritual life. In Zoroastrian cosmogony, water and fire are respectively the second and last primordial elements to have been created, and scripture considers fire to have its origin in the waters. Both water and fire are considered life-sustaining, and both water and fire are represented within the precinct of a fire temple. Zoroastrians usually pray in the presence of some form of fire (which can be considered evident in any source of light), and the culminating rite of the principal act of worship constitutes a "strengthening of the waters". Fire is considered a medium through which spiritual insight and wisdom are gained, and water is considered the source of that wisdom. Both fire and water are also hypostasized as the Yazatas Atar and Anahita, which worship hymns and litanies dedicated to them.

A corpse is considered a host for decay, i.e., of druj. Consequently, scripture enjoins the safe disposal of the dead in a manner such that a corpse does not pollute the good creation. These injunctions are the doctrinal basis of the fast-fading traditional practice of ritual exposure, most commonly identified with the so-called Towers of Silence for which there is no standard technical term in either scripture or tradition. Ritual exposure is currently mainly practiced by Zoroastrian communities of the Indian subcontinent, in locations where it is not illegal and diclofenac poisoning has not led to the virtual extinction of scavenger birds. Other Zoroastrian communities either cremate their dead, or bury them in graves that are cased with lime mortar, though Zoroastrians are keen to dispose of their dead in the most environmental way possible.

While the Parsees in India have traditionally since the 19th century been opposed to proselytizing, and even considered it a crime for which the culprit may face expulsion, Iranian Zoroastrians have never been opposed to conversion, and the practice has been endorsed by the Council of Mobeds of Tehran. While the Iranian authorities do not permit proselytizing within Iran, Iranian Zoroastrians in exile have actively encouraged missionary activities, with the Zarathushtrian Assembly in Los Angeles and the International Zoroastrian Centre in Paris as two prominent organizations and the Federation of Zoroastrian Associations of North America being in favor of conversion and welcoming to converts. Converts from both traditionally Persian and non-Persian ethnicities have even been welcomed at international events, even attending and speaking at events such as the World Zoroastrian Congress and the World Zoroastrian Youth Congress. Zoroastrians are encouraged to marry others of the same faith, but this is not a requirement outside of traditionalist communities where it is strictly enforced in regards to women marrying outside of the faith but not men.

History :

Painted

clay and alabaster head of a Zoroastrian priest wearing a distinctive

Bactrian-style headdress, Takhti-Sangin, Tajikistan, Greco-Bactrian

kingdom, 3rd–2nd century BCE

The roots of Zoroastrianism are thought to have emerged from a common prehistoric Indo-Iranian religious system dating back to the early 2nd millennium BCE. The prophet Zoroaster himself, though traditionally dated to the 6th century BCE, is thought by many modern historians to have been a reformer of the polytheistic Iranian religion who lived in the 10th century BCE. Zoroastrianism as a religion was not firmly established until several centuries later. Zoroastrianism enters recorded history in the mid-5th century BCE. Herodotus' The Histories (completed c. 440 BCE) includes a description of Greater Iranian society with what may be recognizably Zoroastrian features, including exposure of the dead.

The Histories is a primary source of information on the early period of the Achaemenid era (648–330 BCE), in particular with respect to the role of the Magi. According to Herodotus, the Magi were the sixth tribe of the Medes (until the unification of the Persian empire under Cyrus the Great, all Iranians were referred to as "Mede" or "Mada" by the peoples of the Ancient World) and wielded considerable influence at the courts of the Median emperors.

Following the unification of the Median and Persian empires in 550 BCE, Cyrus the Great and later his son Cambyses II curtailed the powers of the Magi after they had attempted to sow dissent following their loss of influence. In 522 BCE, the Magi revolted and set up a rival claimant to the throne. The usurper, pretending to be Cyrus' younger son Smerdis, took power shortly thereafter. Owing to the despotic rule of Cambyses and his long absence in Egypt, "the whole people, Persians, Medes and all the other nations" acknowledged the usurper, especially as he granted a remission of taxes for three years.

Darius I and later Achaemenid emperors acknowledged their devotion to Ahura Mazda in inscriptions, as attested to several times in the Behistun inscription, and appear to have continued the model of coexistence with other religions. Whether Darius was a follower of the teachings of Zoroaster has not been conclusively established as there is no indication of note that worship of Ahura Mazda was exclusively a Zoroastrian practice.

According to later Zoroastrian legend (Denkard and the Book of Arda Viraf), many sacred texts were lost when Alexander the Great's troops invaded Persepolis and subsequently destroyed the royal library there. Diodorus Siculus's Bibliotheca historica, which was completed circa 60 BCE, appears to substantiate this Zoroastrian legend. According to one archaeological examination, the ruins of the palace of Xerxes bear traces of having been burned. Whether a vast collection of (semi-)religious texts "written on parchment in gold ink", as suggested by the Denkard, actually existed remains a matter of speculation, but it is unlikely.

Alexander's conquests largely displaced Zoroastrianism with Hellenistic beliefs, though the religion continued to be practiced many centuries following the demise of the Achaemenids in mainland Persia and the core regions of the former Achaemenid Empire, most notably Anatolia, Mesopotamia, and the Caucasus. In the Cappadocian kingdom, whose territory was formerly an Achaemenid possession, Persian colonists, cut off from their co-religionists in Iran proper, continued to practice the faith [Zoroastrianism] of their forefathers; and there Strabo, observing in the first century B.C., records (XV.3.15) that these "fire kindlers" possessed many "holy places of the Persian Gods", as well as fire temples. Strabo further states that these were "noteworthy enclosures; and in their midst there is an altar, on which there is a large quantity of ashes and where the magi keep the fire ever burning." It was not until the end of the Parthian period (247 b.c.–a.d. 224) that Zoroastrianism would receive renewed interest.

Late

antiquity :

Due to its ties to the Christian Roman Empire, Persia's arch-rival since Parthian times, the Sassanids were suspicious of Roman Christianity, and after the reign of Constantine the Great, sometimes persecuted it. The Sassanid authority clashed with their Armenian subjects in the Battle of Avarayr (a.d. 451), making them officially break with the Roman Church. But the Sassanids tolerated or even sometimes favored the Christianity of the Church of the East. The acceptance of Christianity in Georgia (Caucasian Iberia) saw the Zoroastrian religion there slowly but surely decline, but as late the 5th century a.d. it was still widely practised as something like a second established religion.

Decline in the Middle Ages :

Most of the Sassanid Empire was overthrown by the Arabs over the course of 16 years in the 7th century. Although the administration of the state was rapidly Islamicized and subsumed under the Umayyad Caliphate, in the beginning "there was little serious pressure" exerted on newly subjected people to adopt Islam. Because of their sheer numbers, the conquered Zoroastrians had to be treated as dhimmis (despite doubts of the validity of this identification that persisted down the centuries), which made them eligible for protection. Islamic jurists took the stance that only Muslims could be perfectly moral, but "unbelievers might as well be left to their iniquities, so long as these did not vex their overlords." In the main, once the conquest was over and "local terms were agreed on", the Arab governors protected the local populations in exchange for tribute.

The Arabs adopted the Sassanid tax-system, both the land-tax levied on land owners and the poll-tax levied on individuals, called jizya, a tax levied on non-Muslims (i.e., the dhimmis). In time, this poll-tax came to be used as a means to humble the non-Muslims, and a number of laws and restrictions evolved to emphasize their inferior status. Under the early orthodox caliphs, as long as the non-Muslims paid their taxes and adhered to the dhimmi laws, administrators were enjoined to leave non-Muslims "in their religion and their land." (Caliph Abu Bakr, qtd. in Boyce 1979, p. 146).

Under Abbasid rule, Muslim Iranians (who by then were in the majority) in many instances showed severe disregard for and mistreated local Zoroastrians. For example, in the 9th century, a deeply venerated cypress tree in Khorasan (which Parthian-era legend supposed had been planted by Zoroaster himself) was felled for the construction of a palace in Baghdad, 2,000 miles (3,200 km) away. In the 10th century, on the day that a Tower of Silence had been completed at much trouble and expense, a Muslim official contrived to get up onto it, and to call the adhan (the Muslim call to prayer) from its walls. This was turned into a pretext to annex the building.

Ultimately, Muslim scholars like Al-Biruni found little records left of the belief of for instance the Khawarizmians because figures like Qutayba ibn Muslim "extinguished and ruined in every possible way all those who knew how to write and read the Khawarizmi writing, who knew the history of the country and who studied their sciences." As a result, "these things are involved in so much obscurity that it is impossible to obtain an accurate knowledge of the history of the country since the time of Islam…"

Conversion

:

In time, a tradition evolved by which Islam was made to appear as a partly Iranian religion. One example of this was a legend that Husayn, son of the fourth caliph Ali and grandson of Islam's prophet Muhammad, had married a captive Sassanid princess named Shahrbanu. This "wholly fictitious figure" was said to have borne Husayn a son, the historical fourth Shi'a imam, who claimed that the caliphate rightly belonged to him and his descendants, and that the Umayyads had wrongfully wrested it from him. The alleged descent from the Sassanid house counterbalanced the Arab nationalism of the Umayyads, and the Iranian national association with a Zoroastrian past was disarmed. Thus, according to scholar Mary Boyce, "it was no longer the Zoroastrians alone who stood for patriotism and loyalty to the past." The "damning indictment" that becoming Muslim was Un-Iranian only remained an idiom in Zoroastrian texts.

With Iranian support, the Abbasids overthrew the Umayyads in 750, and in the subsequent caliphate government—that nominally lasted until 1258—Muslim Iranians received marked favor in the new government, both in Iran and at the capital in Baghdad. This mitigated the antagonism between Arabs and Iranians, but sharpened the distinction between Muslims and non-Muslims. The Abbasids zealously persecuted heretics, and although this was directed mainly at Muslim sectarians, it also created a harsher climate for non-Muslims.Although the Abbasids were deadly foes of Zoroastrianism, the brand of Islam they propagated throughout Iran became ever more "Zoroastrianized", making it easier for Iranians to embrace Islam.

Survival :

The fire temple of Baku, c. 1860 Despite economic and social incentives to convert, Zoroastrianism remained strong in some regions, particularly in those furthest away from the Caliphate capital at Baghdad. In Bukhara (in present-day Uzbekistan), resistance to Islam required the 9th-century Arab commander Qutaiba to convert his province four times. The first three times the citizens reverted to their old religion. Finally, the governor made their religion "difficult for them in every way", turned the local fire temple into a mosque, and encouraged the local population to attend Friday prayers by paying each attendee two dirhams. The cities where Arab governors resided were particularly vulnerable to such pressures, and in these cases the Zoroastrians were left with no choice but to either conform or migrate to regions that had a more amicable administration.

The 9th century came to define the great number of Zoroastrian texts that were composed or re-written during the 8th to 10th centuries (excluding copying and lesser amendments, which continued for some time thereafter). All of these works are in the Middle Persian dialect of that period (free of Arabic words), and written in the difficult Pahlavi script (hence the adoption of the term "Pahlavi" as the name of the variant of the language, and of the genre, of those Zoroastrian books). If read aloud, these books would still have been intelligible to the laity. Many of these texts are responses to the tribulations of the time, and all of them include exhortations to stand fast in their religious beliefs. Some, such as the "Denkard", are doctrinal defenses of the religion, while others are explanations of theological aspects (such as the Bundahishn's) or practical aspects (e.g., explanation of rituals) of it.

Fire temple in Yazd

Museum of Zoroastrians in Kerman In Khorasan in northeastern Iran, a 10th-century Iranian nobleman brought together four Zoroastrian priests to transcribe a Sassanid-era Middle Persian work titled Book of the Lord (Khwaday Namag) from Pahlavi script into Arabic script. This transcription, which remained in Middle Persian prose (an Arabic version, by al-Muqaffa, also exists), was completed in 957 and subsequently became the basis for Firdausi's Book of Kings. It became enormously popular among both Zoroastrians and Muslims, and also served to propagate the Sassanid justification for overthrowing the Arsacids (i.e., that the Sassanids had restored the faith to its "orthodox" form after the Hellenistic Arsacids had allowed Zoroastrianism to become corrupt).

Among migrations were those to cities in (or on the margins of) the great salt deserts, in particular to Yazd and Kerman, which remain centers of Iranian Zoroastrianism to this day. Yazd became the seat of the Iranian high priests during Mongol Il-Khanate rule, when the "best hope for survival [for a non-Muslim] was to be inconspicuous." Crucial to the present-day survival of Zoroastrianism was a migration from the northeastern Iranian town of "Sanjan in south-western Khorasan", to Gujarat, in western India. The descendants of that group are today known as the Parsis—"as the Gujaratis, from long tradition, called anyone from Iran"—who today represent the larger of the two groups of Zoroastrians.

The struggle between Zoroastrianism and Islam declined in the 10th and 11th centuries. Local Iranian dynasties, "all vigorously Muslim," had emerged as largely independent vassals of the Caliphs. In the 16th century, in one of the early letters between Iranian Zoroastrians and their co-religionists in India, the priests of Yazd lamented that "no period [in human history], not even that of Alexander, had been more grievous or troublesome for the faithful than 'this millennium of the demon of Wrath'."

Modern :

Sadeh in Tehran, 2011 Zoroastrianism has survived into the modern period, particularly in India, where it has been present since about the 9th century.

Today Zoroastrianism can be divided in two main schools of thought: reformists and traditionalists. Traditionalists are mostly Parsis and accept, beside the Gathas and Avesta, also the Middle Persian literature and like the reformists mostly developed in their modern form from 19th century developments. They generally do not allow conversion to the faith and, as such, for someone to be a Zoroastrian they must be born of Zoroastrian parents. Some traditionalists recognize the children of mixed marriages as Zoroastrians, though usually only if the father is a born Zoroastrian. Reformists tend to advocate a "return" to the Gathas, the universal nature of the faith, a decrease in ritualization, and an emphasis on the faith as philosophy rather than religion. Not all Zoroastrians identify with either school and notable examples are getting traction including Neo-Zoroastrians/Para-Zoroastrians, which are usually radical reinterpretations of Zoroastrianism appealing towards Western concerns, and Revivalists, who center the idea of Zoroastrianism as a living religion and advocate the revival and maintenance of old rituals and prayers while supporting ethical and social progressive reforms. Both of these latter schools tend to center the Gathas without outright rejecting other texts except the Vendidad. Ilm-e-Khshnoom and the Pundol Group are Zoroastrian mystical schools of thought popular among a small minority of the Parsi community inspired mostly by 19th-century theosophy and typified by a spiritual ethnocentric mentality.

From the 19th century onward, the Parsis gained a reputation for their education and widespread influence in all aspects of society. They played an instrumental role in the economic development of the region over many decades; several of the best-known business conglomerates of India are run by Parsi-Zoroastrians, including the Tata, Godrej, Wadia families, and others.

Though the Armenians share a rich history affiliated with Zoroastrianism (that eventually declined with the advent of Christianity), reports indicate that there were Zoroastrian Armenians in Armenia until the 1920s. A comparatively minor population persisted in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Persia, and a growing large expatriate community has formed in the United States mostly from India and Iran, and to a lesser extent in the United Kingdom, Canada and Australia.

At the request of the government of Tajikistan, UNESCO declared 2003 a year to celebrate the "3000th anniversary of Zoroastrian culture", with special events throughout the world. In 2011 the Tehran Mobeds Anjuman announced that for the first time in the history of modern Iran and of the modern Zoroastrian communities worldwide, women had been ordained in Iran and North America as mobedyars, meaning women assistant mobeds (Zoroastrian clergy). The women hold official certificates and can perform the lower-rung religious functions and can initiate people into the religion.

Relation to other religions and cultures :

The Achaemenid Empire in the 5th century BCE was the largest empire in history by percentage of world population Some scholars believe that key concepts of Zoroastrian eschatology and demonology influenced the Abrahamic religions. On the other hand, Zoroastrianism itself inherited ideas from other belief systems and, like other "practiced" religions, accommodates some degree of syncretism, with Zoroastrianism in Sogdia, the Kushan Empire, Armenia, China, and other places incorporating local and foreign practices and deities. Zoroastrian influences on Hungarian, Slavic, Ossetian, Turkic and Mongol mythologies have also been noted, all of which bearing extensive light-dark dualisms and possible sun god theonyms related to Hvare-khshaeta.

Indo-Iranian

origins :

Manichaeism

:

But they are quite different. Manichaeism equated evil with matter and good with spirit, and was therefore particularly suitable as a doctrinal basis for every form of asceticism and many forms of mysticism. Zoroastrianism, on the other hand, rejects every form of asceticism, has no dualism of matter and spirit (only of good and evil), and sees the spiritual world as not very different from the natural one (the word "paradise", or pairi.daeza, applies equally to both.)

Manichaeism's basic doctrine was that the world and all corporeal bodies were constructed from the substance of Satan, an idea that is fundamentally at odds with the Zoroastrian notion of a world that was created by God and that is all good, and any corruption of it is an effect of the bad.[citation needed]

Present-day

Iran :

Religious

text :

As tradition continues, under the reign of King Valax of the Arsacis Dynasty, an attempt was made to restore what was considered the Avesta. During the Sassanid Empire, Ardeshir ordered Tansar, his high priest, to finish the work that King Valax had started. Shapur I sent priests to locate the scientific text portions of the Avesta that were in the possession of the Greeks. Under Shapur II, Arderbad Mahrespandand revised the canon to ensure its orthodox character, while under Khosrow I, the Avesta was translated into Pahlavi.

The compilation of the Avesta can be authoritatively traced, however, to the Sasanian Empire, of which only fraction survive today if the Middle Persian literature is correct. The later manuscripts all date from after the fall of the Sasanian Empire, the latest being from 1288, 590 years after the fall of the Sasanian Empire. The texts that remain today are the Gathas, Yasna, Visperad and the Vendidad, of which the latter's inclusion is disputed within the faith. Along with these texts is the individual, communal, and ceremonial prayer book called the Khordeh Avesta, which contains the Yashts and other important hymns, prayers, and rituals. The rest of the materials from the Avesta are called "Avestan fragments" in that they are written in Avestan, incomplete, and generally of unknown provenance.

Middle

Persian (Pahlavi) :

Zoroaster

:

Zoroaster rejected many of the gods of the Bronze Age Iranians and their oppressive class structure, in which the Karvis and Karapans (princes and priests) controlled the ordinary people. He also opposed cruel animal sacrifices and the excessive use of the hallucinogenic Haoma plant (possibly a species of ephedra), but did not outright condemn completely either practice in moderate forms.

Zoroaster

in legend :

Zoroaster's ideas were not taken up quickly; he originally only had one convert: his cousin Maidhyoimanha. The local religious authorities opposed his ideas, considering that their faith, power, and particularly their rituals were threatened by Zoroaster's teaching against the bad and overly-complicated ritualization of religious ceremonies. Many did not like Zoroaster's downgrading of the Daevas to evil ones not worthy of worship. After twelve years of little success, Zoroaster left his home.

In the country of King Vishtasp, the king and queen heard Zoroaster debating with the religious leaders of the land and decided to accept Zoroaster's ideas as the official religion of their kingdom after having Zoroaster prove himself by healing the king's favorite horse. Zoroaster is believed to have died in his late 70s, either by murder by a Turanian or old age. Very little is known of the time between Zoroaster and the Achaemenian period, except that Zoroastrianism spread to Western Iran and other regions. By the time of the founding of the Achaemenid Empire, Zoroastrianism is believed to have been already a well-established religion.

Cypress

of Kashmar :

Principal

beliefs :

Faravahar (or Ferohar), one of the primary symbols of Zoroastrianism, believed to be the depiction of a Fravashi or the Khvarenah In Zoroastrianism, Ahura Mazda is the beginning and the end, the creator of everything that can and cannot be seen, the eternal and uncreated, the all-good and source of Asha. In the Gathas, the most sacred texts of Zoroastrianism thought to have been composed by Zoroaster himself, Zoroaster acknowledged the highest devotion to Ahura Mazda, with worship and adoration also given to Ahura Mazda's manifestations (Amesha Spenta) and the other ahuras (Yazata) that support Ahura Mazda.

Daena (din in modern Persian and meaning "that which is seen") is representative of the sum of one's spiritual conscience and attributes, which through one's choice Asha is either strengthened or weakened in the Daena. Traditionally, the manthras, spiritual prayer formulas, are believed to be of immense power and the vehicles of Asha and creation used to maintain good and fight evil. Daena should not be confused with the fundamental principle of Asha, believed to be the cosmic order which governs and permeates all existence, and the concept of which governed the life of the ancient Indo-Iranians. For these, asha was the course of everything observable—the motion of the planets and astral bodies; the progression of the seasons; and the pattern of daily nomadic herdsman life, governed by regular metronomic events such as sunrise and sunset, and was strengthened through truth-telling and following the Threefold Path.

All physical creation (getig) was thus determined to run according to a master plan—inherent to Ahura Mazda—and violations of the order (druj) were violations against creation, and thus violations against Ahura Mazda. This concept of asha versus the druj should not be confused with Western and especially Abrahamic notions of good versus evil, for although both forms of opposition express moral conflict, the asha versus druj concept is more systemic and less personal, representing, for instance, chaos (that opposes order); or "uncreation", evident as natural decay (that opposes creation); or more simply "the lie" (that opposes truth and goodness).Moreover, in the role as the one uncreated creator of all, Ahura Mazda is not the creator of druj, which is "nothing", anti-creation, and thus (likewise) uncreated and developed as the antithesis of existence through choice.

A Parsi Wedding, 1905 In this schema of asha versus druj, mortal beings (both humans and animals) play a critical role, for they too are created. Here, in their lives, they are active participants in the conflict, and it is their spiritual duty to defend Asha, which is under constant assault and would decay in strength without counteraction. Throughout the Gathas, Zoroaster emphasizes deeds and actions within society and accordingly extreme asceticism is frowned upon in Zoroastrianism but moderate forms are allowed within. This was explained as fleeing from the experiences and joys of life, which was the very purpose that the urvan (most commonly translated as the "soul") was sent into the mortal world to collect. The avoidance of any aspect of life which does not bring harm to another and engage in activities that support the druj, which includes the avoidance of the pleasures of life, is a shirking of the responsibility and duty to oneself, one's urvan, and one's family and social obligations.

Central to Zoroastrianism is the emphasis on moral choice, to choose the responsibility and duty for which one is in the mortal world, or to give up this duty and so facilitate the work of druj. Similarly, predestination is rejected in Zoroastrian teaching and the absolute free will of all conscious beings is core, with even divine beings having the ability to choose. Humans bear responsibility for all situations they are in, and in the way they act toward one another. Reward, punishment, happiness, and grief all depend on how individuals live their lives.

In the 19th century, through contact with Western academics and missionaries, Zoroastrianism experienced a massive theological change that still affects it today. The Rev. John Wilson led various missionary campaigns in India against the Parsi community, disparaging the Parsis for their "dualism" and "polytheism" and as having unnecessary rituals while declaring the Avesta to not be "divinely inspired". This caused mass dismay in the relatively uneducated Parsi community, which blamed its priests and led to some conversions towards Christianity. The arrival of the German orientalist and philologist Martin Haug led to a rallied defense of the faith through Haug's reinterpretation of the Avesta through Christianized and European orientalist lens. Haug postulated that Zoroastrianism was solely monotheistic with all other divinities reduced to the status of angels while Ahura Mazda became both omnipotent and the source of evil as well as good. Haug's thinking was subsequently disseminated as a Parsi interpretation, thus corroborating Haug's theory, and the idea became so popular that it is now almost universally accepted as doctrine though being reevaluated in modern Zoroastrianism and academia.

Throughout Zoroastrian history, shrines and temples have been the focus of worship and pilgrimage for adherents of the religion. Early Zoroastrians were recorded as worshiping in the 5th century BCE on mounds and hills where fires were lit below the open skies. In the wake of Achaemenid expansion, shrines were constructed throughout the empire and particularly influenced the role of Mithra, Aredvi Sura Anahita, Verethragna and Tishtrya, alongside other traditional Yazata who all have hymns within the Avesta and also local deities and culture-heroes. Today, enclosed and covered fire temples tend to be the focus of community worship where fires of varying grades are maintained by the clergy assigned to the temples.

Cosmology:

Creation of the universe :

While Ahura Mazda created the universe and humankind, Angra Mainyu, whose very nature is to destroy, miscreated demons, evil daevas, and noxious creatures (khrafstar) such as snakes, ants, and flies. Angra Mainyu created an opposite, evil being for each good being, except for humans, which he found he could not match. Angra Mainyu invaded the universe through the base of the sky, inflicting Gayomard and the bull with suffering and death. However, the evil forces were trapped in the universe and could not retreat. The dying primordial man and bovine emitted seeds, which were protect by Mah, the Moon. From the bull's seed grew all beneficial plants and animals of the world and from the man's seed grew a plant whose leaves became the first human couple. Humans thus struggle in a two-fold universe of the material and spiritual trapped and in long combat with evil. The evils of this physical world are not products of an inherent weakness, but are the fault of Angra Mainyu's assault on creation. This assault turned the perfectly flat, peaceful, and ever day-lit world into a mountainous, violent place that is half night.

Eschatology:

Renovation and judgment :

Individual judgment at death is at the Chinvat Bridge ("bridge of judgement" or "bridge of choice"), which each human must cross, facing a spiritual judgment, though modern belief is split as to whether it is representative of a mental decision during life to choose between good and evil or an afterworld location. Humans' actions under their free will through choice determine the outcome. According to tradition, the soul is judged by the Yazatas Mithra, Sraosha, and Rashnu, where depending on the verdict one is either greeted at the bridge by a beautiful, sweet-smelling maiden or by an ugly, foul-smelling old hag representing their Daena affected by their actions in life. The maiden leads the dead safely across the bridge, which widens and becomes pleasant for the righteous, towards the House of Song. The hag leads the dead down a bridge that narrows to a razor's edge and is full of stench until the departed falls off into the abyss towards the House of Lies. Those with a balance of good and evil go to Hamistagan, a neutral place of waiting where according to the Dadestan-i Denig, a Middle Persian work from the 9th century, the souls of the departed can relive their lives and conduct good deeds to raise themselves towards the House of Song or await the final judgement and the mercy of Ahura Mazda.

The House of Lies is considered temporary and reformative; punishments fit the crimes, and souls do not rest in eternal damnation. Hell contains foul smells and evil food, a smothering darkness, and souls are packed tightly together although they believe they are in total isolation.

In ancient Zoroastrian eschatology, a 3,000-year struggle between good and evil will be fought, punctuated by evil's final assault. During the final assault, the sun and moon will darken and humankind will lose its reverence for religion, family, and elders. The world will fall into winter, and Angra Mainyu's most fearsome miscreant, Azi Dahaka, will break free and terrorize the world.

According to legend, the final savior of the world, known as the Saoshyant, will be born to a virgin impregnated by the seed of Zoroaster while bathing in a lake. The Saoshyant will raise the dead—including those in all afterworlds—for final judgment, returning the wicked to hell to be purged of bodily sin. Next, all will wade through a river of molten metal in which the righteous will not burn but through which the impure will be completely purified. The forces of good will ultimately triumph over evil, rendering it forever impotent but not destroyed. The Saoshyant and Ahura Mazda will offer a bull as a final sacrifice for all time and all humans will become immortal. Mountains will again flatten and valleys will rise; the House of Song will descend to the moon, and the earth will rise to meet them both. Humanity will require two judgments because there are as many aspects to our being: spiritual (menog) and physical (getig). Thus, Zoroastrianism can be said to be a universalist religion with respect to salvation in that all souls are redeemed at the final judgement.

Ritual

and prayer :

The incorporation of cultural and local rituals is quite common and traditions have been passed down in historically Zoroastrian communities such as herbal healing practices, wedding ceremonies, and the like. Traditionally, Zoroastrian rituals have also included shamanic elements involving mystical methods such as spirit travel to the invisible realm and involving the consumption of fortified wine, Haoma, mang, and other ritual aids. Historically, Zoroastrians are encouraged to pray the five daily Gahs and to maintain and celebrate the various holy festivals of the Zoroastrian calendar, which can differ from community to community. Zoroastrian prayers, called manthras, are conducted usually with hands outstretched in imitation of Zoroaster's prayer style described in the Gathas and are of a reflectionary and supplicant nature believed to be endowed with the ability to banish evil. Devout Zoroastrians are known to cover their heads during prayer, either with traditional topi, scarves, other headwear, or even just their hands. However, full coverage and veiling which is traditional in Islamic practice is not a part of Zoroastrianism and Zoroastrian women in Iran wear their head coverings displaying hair and their faces to defy mandates by the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Demographics :

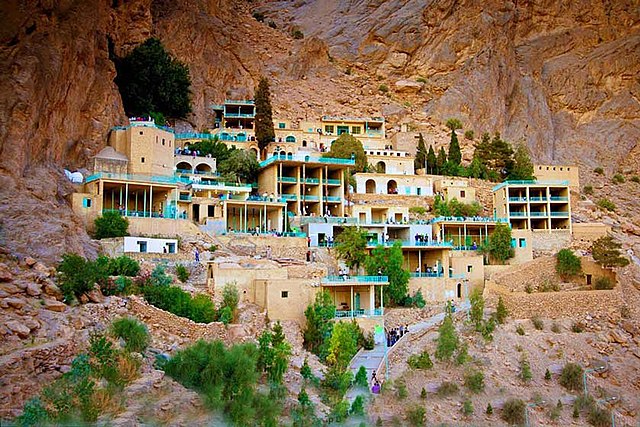

The sacred Zoroastrian pilgrimage shrine of Chak Chak in Yazd, Iran Zoroastrian communities internationally tend to comprise mostly two main groups of people: Indian Parsis and Iranian Zoroastrians. According to a study in 2012 by the Federation of Zoroastrian Associations of North America, the number of Zoroastrians worldwide was estimated to be between 111,691 and 121,962. The number is imprecise because of diverging counts in Iran.

Small Zoroastrian communities may be found all over the world, with a continuing concentration in Western India, Central Iran, and Southern Pakistan. Zoroastrians of the diaspora are primarily located in the United States, Great Britain and the former British colonies, particularly Canada and Australia, and usually anywhere where there is a strong Iranian and Gujarati presence.

In

South Asia :

Parsi Navjote ceremony (rites of admission into the Zoroastrian faith) India is considered to be home to the single largest Zoroastrian population in the world. When the Islamic armies, under the first caliphs, invaded Persia, those locals who were unwilling to convert to Islam sought refuge, first in the mountains of Northern Iran, then the regions of Yazd and its surrounding villages. Later, in the ninth century CE, a group sought refuge in the western coastal region of India, and also scattered to other regions of the world. Following the fall of the Sassanid Empire in 651 CE, many Zoroastrians migrated. Among them were several groups who ventured to Gujarat on the western shores of the Indian subcontinent, where they finally settled. The descendants of those refugees are today known as the Parsis. The year of arrival on the subcontinent cannot be precisely established, and Parsi legend and tradition assigns various dates to the event.

In the Indian census of 2001, the Parsis numbered 69,601, representing about 0.006% of the total population of India, with a concentration in and around the city of Mumbai. Due to a low birth rate and high rate of emigration, demographic trends project that by 2020 the Parsis will number only about 23,000 or 0.002% of the total population of India. By 2008, the birth-to-death ratio was 1:5; 200 births per year to 1,000 deaths. India's 2011 Census recorded 57,264 Parsi Zoroastrians.

Pakistan

:

Iran,

Iraq and Central Asia :

Communities exist in Tehran, as well as in Yazd, Kerman and Kermanshah, where many still speak an Iranian language distinct from the usual Persian. They call their language Dari (not to be confused with the Dari of Afghanistan). Their language is also called Gavri or Behdini, literally "of the Good Religion". Sometimes their language is named for the cities in which it is spoken, such as Yazdi or Kermani. Iranian Zoroastrians were historically called Gabrs, originally without a pejorative connotation but in the present-day derogatorily applied to all non-Muslims.

The number of Kurdish Zoroastrians, along with those of non-ethnic converts, has been estimated differently.The Zoroastrian Representative of the Kurdistan Regional Government in Iraq has claimed that as many as 100,000 people in Iraqi Kurdistan have converted to Zoroastrianism recently, with community leaders repeating this claim and speculating that even more Zoroastrians in the region are practicing their faith secretly. However, this has not been confirmed by independent sources.

The surge in Kurdish Muslims converting to Zoroastrianism, the faith of their ancestors is largely attributed to disillusionment with Islam after the years of violence and barbarism perpetrated by the ISIS jihadi group.

Western

world :

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

_p012_BAKU,_FIRE_TEMPLE_(cropped).jpg)

.jpg)