PAHLAV

EMPIRE OF DRAVIDIA

History

of Iran

India's

Parthian Colony

On the origin of the Pallava Empire of Dravidia

By : Dr. Samar Abbas, May 14, 2003

Revealing

the ancient Pallava Dynasty of Dravidia to be of the Iranic race,

and as constituting a branch of the Pahlavas, Parthavas or Parthians

of Persia. Uncovering the consequent Iranic foundations of Classical

Dravidian architecture. Describing A Short History of the Pallavas

of Tamil Nadu, including the cataclysmic 100-Years' Maratha-Tamil

War. The modern descendants of Pallavas discovered amongst the Chola

Vellalas of northern Tamil Nadu and Reddis of Andhra.

1-

Pallavas, Pahlavas, Parthavas, Parthians and Persians :

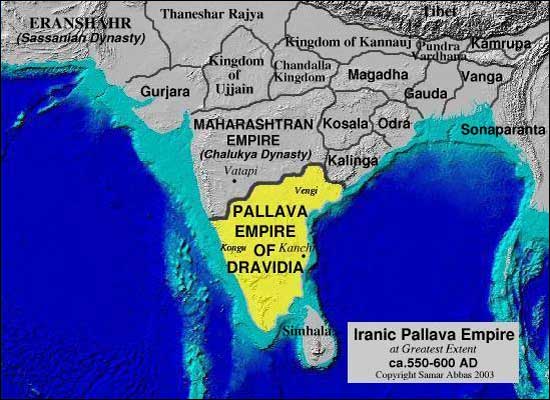

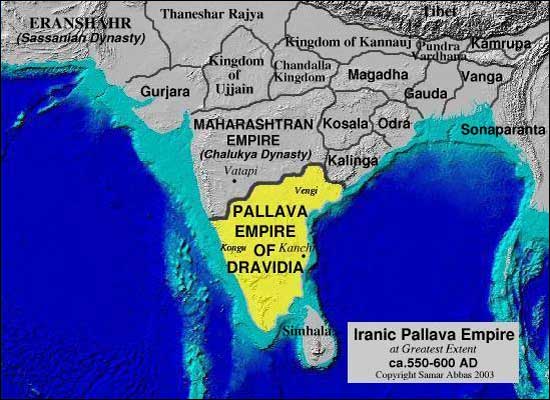

Fig.1: Map of Pallava Empire at Greatest Extent c.550-600

AD1.1. Introduction

The Pallava Empire was the largest and most powerful South Asian

state in its time, ranking as one of the glorious empires of world

history. At its height it covered an area larger than France, England

and Germany combined. It encompassed all the present-day Dravidian

nations, including the Tamil, Telugu, Malayali and Kannada tracts

within its far-flung borders (see map). The foundations of classical

Dravidian architecture were established by these powerful rulers,

who left behind fantastic sculptures and magnificent temples which

survive to this very day. Initially, the similarity of the words

"Pallava" and "Pahlava" had led 19th-century

researchers to surmise an Iranic origin for the Pallavas. Since

then, a mountain of historical, anthropological, and linguistic

evidence has accumulated to conclusively establish that the Pallavas

were of Parthian origin.

1.2.

Occurrence of Parsas across the world :

The wide occurrence of the Iranic root-word Par in various place-names

proves the dispersion of the Pars or Persians across much of Asia

in ancient times. Thus, Persia, Persepolis, Pasargadae ("Gates

of Parsa") and "Parthaunisa (ancient city, Parthia)"

or Nisa (Enc.Brit., vol.9, p.173) are all constructed from the ancient

Iranic root-word Pars. In this regard, the learned Prof. Waddell

notes in his masterpiece "The Makers of Civilization":

"Barahsi or Parahsi [of Akkadian inscriptions] now transpires

to be the original of the ancient Persis province of the Greeks,

with its old capital at Anshan or Persepolis, the central province

of Persia to the East of Elam and the source of our modern names

of "Persia" and "Parsi". And it is another instance

of the remarkable persistence of old territorial names" (Waddell

1929, p.216). The Parsumas mentioned in Assyrian annals are also

generally identified with the Persians, and the Zoroastrian Parsis

of Maharashtra are clearly of Persic descent. Moreover, the word

Parthian is itself derived from Parsa, as the Encyclopedia Britannica

notes: "The first certain occurrence of the name is as Parthava

in the Bisitun inscription (c.520 BC) of the Achaemenian king Darius

I, but Parthava may be only a dialectal variation

of the name Parsa (Persian)." (Enc.Brit. Vol.9, p.173)

Further,

Euphrates means `Persian river' in Greek, while the biblical Perizzites

of Palestine have been linked with the Iranians (Derakhshani 1999,

Kap.8). The word "Pastho" in turn has also been connected

with the Persians, as the eminent Iranologist Prof. P.Oktor Skjærvø

notes :

"It

is not impossible that Old Persian Parsa is descended from an earlier

form *Parswa, but that cannot be proved. On the other hand, modern

Pašto (the language of the Afghans) must be descended from

Old Iranian *Parsawa, which is very close to the Assyrian forms.

Finally, Old Persian Parsava is also not unlike these forms."

(Skjærvø 1995, p.156)

The distinguished Professor Michael Witzel of Harvard University

has further identified the Parnoi as the Pani mentioned in the Vedas

:

"Another North Iranian tribe were the (Grk.) Parnoi, Ir. *Parna.

They have for long been connected with another traditional enemy

of the Aryans, the Pani (RV+). Their Vara-like forts with their

sturdy cow stables have been compared with the impressive forts

of the Bactria-Margiana (BMAC) and the eastern Ural Sintashta cultures

(Parpola 1988, Witzel 2000), while similar ones are still found

today in the Hindukush." (Witzel 2001, p.16)

Thus, the Persians, Parthians, Pashtos, Panis and Perizzites are

all offhoots of the ancient proto-Persians. This testifies to the

supreme achievements of the glorious Persian branch of the Iranic

race in civilizing and colonizing Southern Asia. All this, of course,

is well known and the subject of numerous books (cf, eg. Derakhshani

1999). Less famous is the fact that the magnificent Pallava Dynasty

of Southern India was also of Iranic descent.

1.3.

Pahlava History in Iran :

The Pahlavas made important contributions to Iranian civilization.

The modern Farsi tongue is derived from the Old Parthian language,

as noted by the Encyclopedia Britannica: "Of the modern Iranian

languages, by far the most widely spoken is Persian, which, as already

indicated, developed from Middle Persian and Parthian, with elements

from other Iranian languages such as Sogdian, as early as the 9th

century AD." (Enc.Brit.vol.22, p.627) Furthermore, "Middle

Persian [Sassanian Pahlava] and Parthian were doubtlessly similar

enough to be mutually intelligible." (Enc.Brit.22.624); a statement

which further confirms the identity of the Pahlavas and the Parthians.

Moreover,

the Pahlava alphabet is the ancestor of the Sasanian Persian alphabet:

"The Pahlava alphabet developed from the Aramaic alphabet and

occurs in at least three local varieties: northwestern, called Pahlavik

or Arsacid; southwestern, called Parsik or Sasanian, and eastern"

(Enc.Brit.vol.9, p.62). Some authorities seem to insist that it

was the Semitic Aramaic alphabet which gave birth to the Parthian

alphabet. This is not so; it was actually the Assyrian variant which

developed into the Pahlava characters, just as it was Assyrian art,

not Aramaean, which inspired later Achaemenid culture. The Achaemenid

empire was in many ways the successor-state of the Assyrian empire.

1.4.

Pallavas of Dravidia as Pahlavis :

The Pallavas are first attested in the northern part of Tamil Nadu,

precisely the geographical region expected for an invading group.

This, together with the evident phonetic similarity between the

words "Pallava" and "Pahlava", has long led

researchers to advocate a Parthian origin of the Pallavas:

"Theory of Parthian origin: The exponents of this theory supported

the Parthian origin of the Pallavas. According to this school, the

Pallavas were a northern tribe of Parthian origin constituting a

clan of the nomads having come to India from Persia. Unable to settle

down in northern India they continued their movements southward

until they reached Kanchipuram5. The late Venkayya supported this

view 6 and even attempted to determine the date of their migration

to the South. A crown resembling an elephant's head was issued by

the early Pallava kings and is referred to in the Vaikunthaperumal

temple sculptures at the time of Nandivarman Pallavamalla's ascent

to the throne. A similiar crown was in use by the early Bactrian

kings in the 2nd century BC and figures on the coins of Demetrius.

It is presumed on this basis that there is some connection between

the Pallavas of Kanchi and Bactrian kings. [ 5. Mysore Gazetteer,

I. p.303-304; 6. ASR {Ann.Rep.ASI), 1906-1907, p.221 ]." (Minakshi

1977, p.4)

As Venkayya notes,

"Oblong earthenware sarcophagi, both mounted and unmounted,

have been reported from several sites in S.India from Maski in the

North to Puduhotta in the South. Their distribution in what was

during historical period the region of Pallava hegemony is not without

significance as stated by Professor Weber." (Venkayya 1907,

p.219-220)

Philogists concur in connecting the names Pahlava, Parthava, Parthian

and Pallava :

"The word Pahlava, from which the name Pallava appears to be

derived, is believed to be a corruption of Parthava, Parthiva or

Parthia, and Dr. Bhandarkar calls the Indo-Parthians Pahlavas. The

territories of the Indo-Parthians lay in Kandahar and Seistan, but

extended during the reign of Gondophares (about AD 20 to 60) into

the Western Punjab and the valley of the lower Indus. The Andhra

king Gotamiputra, whose dominions lay in the Dakhan, claims to have

defeated about AD 130 the Palhavas along with the Sakas and Yavanas.

In the Junagadh inscription of the Ksatrapa king Rudradaman belonging

to about AD 150, mention is made of a Pallava minister of his named

Suvisakha." (Venkayya 1907, p.218)

2-

Evidence for Parthian Descent of Pallavas :

A

whole mountain of evidence from various fields of science support

the Parthian, and hence Iranic, origin of the Pallavas. It would

be of interest to summarise the evidence here.

2.1.

Archaeology :

Archaeologists note the occurrence of oblong earthenware coffins

in sites coinciding with the region of Pallava hegemony :

"Oblong earthenware sarcophagi, both mounted and unmounted,

have been reported from several sites in S.India from Maski in the

North to Puduhotta in the South. Their distribution in what was

during historical period the region of Pallava hegemony is not without

significance in the light of a Parthian origin of the Pallavas suggested

by Heras (Heras, H.J.: Origin of the Pallavas, J. of the Univ. of

Bombay, Vol. IV, Pt IV, 1936) and afterwards by Venkatasubba Iyer

("A new link between the Indo-Parthians and Pallavas of Kanchi",

J. of Indian History, Vol. XXIV, Pts 1 & 2, 1945). A possible

link between the Parthians and the Pallavas is the mode of tying

the waist-band as evidenced by their statuary (compare the knot

in Pallava waist-band with knot in Parthian waist-band ...)"

(Nair 1977, p.85)

2.2. Administration :

Pallava administration was based on the Maurya pattern, which was

in turn based on that of the Achaemenid Empire.

"[T]he early Pallava kings issued their charters in Prakrit

and Sanskrit and not in Tamil and their early administration was

based on the Mauryan-Satavahana pattern, essentially northern in

character. Their gotra (Bharadvaja) also stands in the way of their

identification with the Kurumbar who had no gotra claims."

(Minakshi 1977, p.5)

2.3. Dress :

The dress of the Pallavas is cleary Parthian. Thus, Nair notes,

A possible link between the Parthians and the Pallavas is the mode

of tying the waist-band as evidenced by their statuary (compare

the knot in Pallava waist-band with knot in Parthian waist-band

...)" (Nair 1977, p.85)

The entire city of Mamallapuram or Mahamallapuram in Tamil Nadu

is named after the Pallava King Mahamalla who is celebrated as the

founder of this city. This original Prakrit name "Mahamallapuram"

was later corrupted in the Sanskrit into "Mahabalipuram".

In this regard, Venkayya notes the origin of the name "Mamallapuram":

"[I]n ancient Cola inscriptions found at the Seven Pagodas,

the name of the place is Mamallapuram which is evidently a corruption

of Mahamallapuram, meaning `the city or town (p.234) of Mahamalla.'

I have already mentioned the fact that Mahamalla occurs as a surname

of the Pallava king Narasimhavarman I in a mutilated record at Badami

in the Bombay Presidency. It is thus not unlikely that Mahamallapuram

or Mavalavaram was founded by the Pallava king Narasimhavarman,

the contemporary and opponent of the Calukya Pulikesin II., whose

accession took place about AD. 609. Professor Hultzsch is of opinion

that the earliest inscriptions on the rathas are birudas of a king

named Narasimha. It may, therefore, be concluded that the village

was originally called Mahamallapuram or Mamallapuram, after the

Pallava king Narasimhavarman I., and that the earliest rathas were

cut out by him." (Venkayya 1907, p.233-234)

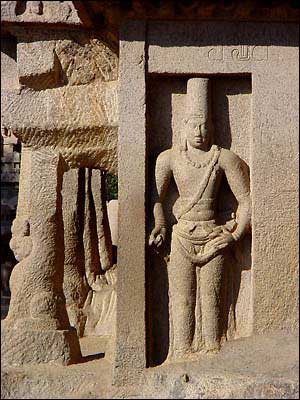

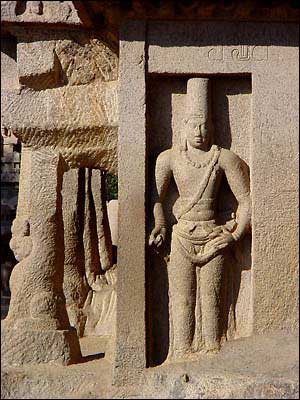

Fig.2:

Pallava King Mamalla or Narasimhavarman I (Dharmaraja Ratha, Mamallapuram,

Tamil Nadu). Note the cylindrical Persian hat, long thin nose and

long-headedness

(Image

by Michael D. Gunther)

Surviving

contemporary sculptures of this celebrated King Mamalla depict him

wearing a typical cylindrical Iranian head-dress. Furthermore, the

elephant-head crown used by Pallava kings resembled those worn by

Bactrian kings (Fig.2).

2.4.

Prakrit Language :

The Pallavas initially propagated Prakrit, a language containing

a much higher percentage of Indo-European words compared to Sanskrit

as it represented a later, and hence purer, heliolatric Indo-European

invasion. "These three Prakrt grants prove that there was a

time when the court language was Prakrt even in Southern India."

(Venkayya 1907, p.223) That they initially did not propagate Sanskrit

or Tamil is significant as it rules out a Vedic or Dravidian origin

for the Pallavas.

2.5.

Toponyms and Personal Names :

Evidence from toponyms (place-names) corroborates the Iranic origin

of Pallavas. For instance, the Pallavas named a city in Tamil Nadu

as Menmatura or Men-Matura, after Mithra, the ancient Iranic Sun-God,

formed from tbe consonantal root MTR. The large town in southern

Tamil Nadu, Madurai, is named after the Sun-temple city of Mathura

in Oudh, which is also based on "Mithra". Further, the

Pallavas had a fondness for Iranic Prakrit personal names such as

Ashok:

"In the Kasakudi plates, Asokavarman is referred to as the

son of king Pallava. Here Asokavarman is evidently a reminiscence

of the Maurya emperor Asoka who lived long before the Pallavas."

(Venkayya 1907,p.240, footnote 8).

The Pallavas thus sought to emulate the Maurya kings, who were of

Iranic origin (Spooner 1915, p.406ff). It is important to note that

the Iranic root-word "Mor" occurs all across the Iranian

world: consider the "Mardian" tribe of Persians mentioned

by Herodotus; "the Avestan name Mourva, the Marga of the Achaemenian

inscriptions" (Spooner 1915, p.406), and the city of Merv,

also known as "Merw, Meru or Maur", whose inhabitants

are known as "Marga and Mourva" (ibid.), the legendary

"Meru" mountain, the "Amorites" or "Amurru"

of Syria and Palestine who possessed an Iranic ruling caste, the

"Amu-Darya" river, "Amol" town just south of

the Caspian, "Marwar" in Rajputana, the Oudh towns of

"Mor-adabad" and "Meerut", the "Maurya"

dynasty of Ashoka, and the "Marut" warriors in India.

2.6. Official Symbolism

To this evidence we may add that the Pallavas had as their crest

the lion, just as the Achaemenids carved lions at Persepolis. Describing

the cave at Siyamangalam, Venkayya notes :

"This was excavated by king Lalitankura, ie. Mahendravarman

I. and was called Avanibhajana-Pallavesvara, Ep.Ind., Vol.VI, p.320.

I recently inspected the cave and the two inscriptions found in

it. The two outer pillars of the cave on which they are engraved

also bear at the top a well-executed lion (one on each of the two

pillars) with the tail folded over its back. The tail resembles

that of the lion figured in No.54, Plate II. of Sir Walter Elliot's

Coins of Southern India, which has been attributed to the Pallavas.

It has therefore to be concluded that the lion was the Pallava crest

at some period or other of their history." (Venkayya 1907,

p.232, ftn.6)

2.7. Anthropology :

The depictions of Pallava nobles on sculptures further confirms

their Iranic origin, for they are depicted as tall and dolichocephalic

(long-headed) along with clearly Iranic features.

Fig.3: Court Scene, Mamallapuram 7th century AD (Pallava). Note

the long-headedness and leptorrhine (long and thin) nose of the

surrounding Iranic courtiers. Contrast this with the platyrrhine

(flat) nose, thick lips and Negroid features of the Dravidian God

Shiva standing with his bull in the centre. Note clear Persepolitan

influence on the pillars. (Image by Michael D. Gunther)

The

long-headedness of these sculptures rules out an Outer Indo-Aryan

origin for the Pallavas, while their leptorrhine noses rule out

a Dravidian origin.

2.8.

Architecture :

The architecture of the Pallavas was clearly based on Iranian forms,

down to the last detail. Pillars especially were copies of Persepolitan

originals (see Fig.4 and Fig.3).

Fig.4: Varaha Cave Temple, Mamallapuram, Tamil Nadu, late 7th century.

Note the clear Achaemenid influence on the pillars, and the Persepolitan

capitals. Flanking lions are reminiscent of Persepolis and Assyria.

(Image by Michael D. Gunther)

2.9.

Legendary Descent :

The traditional genealogy of the Pallavas also points to their Parthian

origins :

"One point which might be taken as proof of the foreign origin

of the Pallavas has to be noted here. The indigenous Ksatriya tribes

(or at least those which were looked upon as such) belonged either

to the solar or to the lunar race. For instance, the Colas belonged

to the solar race and the Pandyas to the lunar. The Ceras seem to

have belonged to the solar race. The Calukyas - both the Eastern

and Western - were of the lunar race. The Rastrakutas were also

of the same race. On the other hand, the Pallavas trace their descent

from the god Brahma but not from the Sun or the Moon, though they

are admitted to have been Ksatriyas. Besides, none of the ancient

kings mentioned in the Puranas figures in the ancestry of the Pallavas.

The indigenous tribes, however, always traced their ancestry from

some of the famous kings known from the Puranas. The Colas, for

instance claimed Manu, Iksvaku, Mandhatr, Mucukunda and Sibi; the

Pandyas were descended from the emperor Pururavas; the C eras had

Sagara, Bhagiratha, Raghu, Dasaratha and Rama for their ancestors.

The Calukyas had a long list of Puranic sovereigns in their ancestry.

The Rastrakutas were descendants of Yadu and belonged to the Satyaki

branch or clan. The Ganga kings of Kalinganagara were descended

from the Moon and claimed Pururavas, Ayus, Nahusa, Yayati and Turvasu

for their ancestors. (Ind. Ant. Vol. XVIII, p.170). The Western

Gangas of Talakad were apparently of the solar race and had Iksvaku

for their ancestor (Mr Rice's Mysore Gazetteer, Vol.I, p.308). The

only king mentioned in the mythical genealogy of the Pallavas is

Asokavarman, son of king Pallava , who, as Prof. Hultzsch rightly

suspects, is probably "a modification of the Maurya emperor

Asoka" (South Ind. Inscrs. Vol.II, p.342). No doubt the earliest

Pallava records were found in the Kistna delta. But this cannot

be taken to point to an indigenous origin of the family. All these

facts together raise the presumption that the Pallavas of Southern

India were not an indigenous tribe in the sense that the Colas,

Pandyas and Ceras were." (Venkayya 1907, p.219, footnote 5)

The above evidences, taken together rather than singly, provide

almost conclusive proof of the Parthian origin of Pallavas.

3- History of the Pallavas :

3.1.

Early History: Adoption of Dravidian Culture :

After immigrating from Parthia, the Pallavas settled down in the

Andhra region. From here they entered northern Tamil Nadu. Initially,

the Pallava Empire was restricted to Tondai-mandalam, the northern

part of Tamil Nadu: "It thus appears that the Pallava dominions

included at the time [Sivaskandavarman, beg. 4th century AD] not

only Kañcipuram and the surrounding province but also the

Telugu country as far north as the river Krsna." (Venkayya

1907, p.222) Subsequently, the Pallavas expanded to conquer large

parts of Andhra:

"The Pallava dominions probably comprised at the time [5th-6th

centuries AD] the modern districts of (p.225) Nellore, Guntur, Kistna,

Kurnool and perhaps also Anantapur, Cuddapah, and Bellary. The Kadambas

of Banavasi, who were originally Brahmanas, threatened to defy the

Pallavas." (Venkayya 1907, p.224-225)

Tamil poets described the boundaries of Tondai-mandalam as follows

:

"According to the Tondamandala-satakam, Tondamandalam (ie.

the Pallava territory) was bounded on the north by the Tirupati

and Kalahasti mountains; on the south by the river Palar; and on

the west by the Ghauts (Taylor's Catalogue, Vol.III, p.29). A verse

attributed to the poetess Auvaiyar describes Tondai-mandalam as

the country bounded by the Pavalamalai, ie. the Eastern Ghauts in

the west; Vengadam, ie. Tirupati in the north; the sea to the east;

and Pinagai, ie. the Southern Pennar in the south. The greatest

length of the province is said to be full 20 kadam or nearly 200

miles.... A variant of the name Tondai-mandalam is Dandaka-nadu,

which is apparently derived from the Sanskrit Dandakaranya, ie the

forest of Dandaka mentioned in the Ramayana and the Puranas."

(Venkayya 1907, p.222, footnote 2)

After settling in Tondai-mandalam, the Pallavas rapidly adopted

the Dravidian culture, religion and language of their subjects.

This case was not unique in history; there are many examples of

ruling classes adopting the culture of those they ruled: consider

the Hellenic Ptolemies in Egypt, the Paleo-Siberian Manchus in China,

the Germanic Lombards in Italy, the Nordic Visigoths in Spain, the

Mongol Il-Khans in Persia, the French-speaking Normans in England,

and the Germanic Carolingians, Merovingians, Burgundians and Franks

of France. Thus, the Pallavas adopted the Old Tamil language and

the Dravidian religion of Shaivism and became vigorous promoters

of Dravidian culture.

3.2.

Expansion of the Pallava Empire :

From

its nucleus in Tondaimandalam, the Pallava Empire expanded in all

directions. The Pan-Dravidian nature of the Pallava empire is manifested

through the extent of their dominions. Thus, the Pallavas vanquished

the Cholas, Cheras and Pandyas and conquered their territories,

uniting Tamil Nadu, Malabar, Karnadu and Telingana into one giant

empire :

"The earliest king of this series is Sinhavisnu, who claims

to have vanquished the Malaya, Kalabhra, Malava, Cola and Pandya

kings, the Simhala king proud of the strength of his arms and the

Keralas." (Venkayya 1907, p.227)

This was the first pan-Dravidian empire in history. Perhaps they

were able to unite the Dravidian nations precisely because they

were outsiders, and hence did not possess any history of feuding

with local clans. Thus, we find the Pallavas conquering all the

three mutually warring Pandya, Cola and Cera kingdoms:

"The Cera, Cola and Pandya kingdoms of the south are mentioned

already in the edicts of the Maurya emperor Asoka. Of their subsequent

history, almost nothing is known from the epigraphical records,

until we get to the period of Pallava rule, when all the three figure

among the tribes conquered by the Pallavas." (Venkayya 1907,

p.237)

After consolidating their rule over the Dravidian nations, the Pallavas

extended their empire to South-East Asia:

"The Pallavas were the emperors of the Dravidian country and

rapidly adopted Tamil ways. Their rule was marked by commercial

enterprise and a limited amount of colonization in South-East Asia,

but they inherited rather than initiated Tamil interference with

Ceylon." (Enc.Brit. Vol.9, p.89)

However, the exact extent of Pallava colonization in South-East

Asia is not clear due to paucity of sources. Even so, the Pallava

Empire was the largest South Asian state of its age, and served

as the model for future pan-Dravidian empires such as that built

by the Cholas.

3.3.

The 100-Years' Maratha-Tamil War (AD 634-747) & Decline :

The Indian equivalent of Europe's Anglo-French 100-Years' War was

the prolonged conflict between Marathas and Tamils under the Chalukyas

and Pallava dynasties which lasted well over a century.

"The history of this period consists mainly of the events of

the war with the Calukyas which lasted almost a century 7 (footnote

7: The war apparently began with the Eastern campaign of Pulikesin

II. which must have taken place some time before AD 634-5 (Ep.Ind.,

Vol.VI, p.3). The last important event of the war is the invasion

of Kañci by the Calukya king Vikramaditya II, who reigned

from AD 733-4 to 746-7. Kirtivarman II, son of Vikramaditya II,

also claims to have led an expedition in his youth against the Pallavas.

... ) and which seems to have been the ultimate cause of the decline

and downfall of both the Pallavas and Calukyas about the middle

of the 8th century." (Venkayya 1907, p.226)

At this point, we may note Mr. Rice's hypothesis that the Calukyas

were Seleucids :

"Mr. Rice says: `The name Calukya bears a suggestive resemblance

to the Greek name Seleukeia, and if the Pallavas were really of

Parthian connection, as their name would imply, we have a plausible

explanation of the inveterate hatred which inscriptions admit to

have existed between the two, and their prolonged struggles may

have been but a sequel of the contests between the Seleucidæ

and the Arsacidæ on the banks of the Tigris and Euphrates.'

(Mysore, Vol.I, p.320)" (Venkayya 1907, p.226, footnote 6)

However, Mr. Rice's suggestion has not been accepted by other historians,

and is merely a phonetic coincidence, for there is no other evidence

of any connection whatsoever between the Calukyas and Seleucids.

Historians

have found several reasons for explaining the bitterness of the

Maratha-Dravidian wars. Venkayya notes the religious aspect of the

conflict, with the Vaishnava Marathas on one side and the Dravidian

Shaivites on the other:

"No satisfactory explanation has, so far, been offered for

this natural enmity between the Pallavas and Calukyas. It is possible

that the hatred had a religious basis. The Pallavas were Saivas

and had the bull for their crest, while the Calukyas were devotees

of the god Vishnu and had the bear for their crest." (Venkayya

1907, p.226, footnote 6)

However,

a far deeper reason contributed to the conflict, namely that of

ethnicity. Abstract theological formulae, on account of their nebulous

definition and easily modified nature, no doubt hardly mattered

to the great majority of inhabitants. Rather, it is race and ethnicity

which combined to make the Pallava-Chalukya conflict especially

bitter. Thus, the so-called Calukya-Pallava dynastic conflict was

in actual fact a racial Maratha-Dravidian war.

On

the one hand were the Marathas speaking Outer Indo-Aryan languages,

of brachycephalic (round-headed) Turanoid race. The survival of

Burushaski - a language isolate linked with the Transcaucasian and

Finno-Ugric languages - in the Himalayas testifies to the immigration

of brachycephalic Turanian peoples into India. The Turanoid Maratha

is thus fair-skinned, short-statured and round-headed. On the other

hand were the long-headed and taller, black-skinned Dravidians of

Sudanic Negroid origin. The Dravidians, however, had a long-headed

Iranic Pallava ruling class. The Iranoid longheads are fairer and

taller than the Dravidoid longheads, who are in turn taller but

darker than the Turanoid Outer Indo-Aryan roundheads. Thus, racial

differences no doubt played, along with language and religion, a

prominent role in the conflict.

At

the outset of the 100-year Maratha-Tamil War, it is the Marathas

who gained the upper hand, defeating the Pallavas and driving them

from the Vengi delta area of Andhra. However, the Pallavas later

defeated the Maharashtrians and sacked their capital Vatapi, annexing

it to the Dravidian Empire :

"The son of Mahendravarman I. was Narasimhavarman I., who retrieved

the fortunes of the family by repeatedly defeating the Colas, Keralas,

Kalabhras and Pandyas. He also claims to have written the word `victory'

as on a plate, on Pulikesin's back, which was caused to be visible

(ie. which was turned in flight after defeat) at several battles.

Narasimhavarman carried the war into Calukya territory and actually

captured Vatapi, their capital. This claim of his is established

by an inscription found at Badami in the Bombay Presidency - the

modern name of Vatapi - from which it appears that Narasimhavarman

bore the title Mahamalla. In later times, too, this Pallava king

was known as Vatapi-konda-Narasingappottaraiyan. Dr. Fleet assigns

the capture of the Calukya capital to about AD 642. 7 The war of

Narasimhavarman with Pulkesin II is mentioned in the Singhalese

chronicle Mahavamsa. It is also hinted in the Tamil Periyapuranam.

The well-known saint Siruttonda, who had his only son cut up and

cooked in order to satisfy the appetite of god Siva disguised as

a devotee, is said to have reduced to dust the city of Vatapi for

his royal master, who could be no other than the Pallava king Narasimhavarman.9

[footnote 9: Ep.Ind. Vol.III, p.277. . Paramesvaravarman I. also

claims to have destroyed the Calukya capital. A still later conquest

of Vatapi is also known. It was effected by a Kodumbalur chief,

apparently during the second half of the 9th century. (Ann.Rep.

on Epi. for 1907-8, Part II, para.85)] The Saiva saint Tiruñanasambandar

visited Siruttonda at this native village fo Tiruccengattangudi,

and the Devara hymn dedicated to the Siva temple of the village

mentions the latter and thus helps to fix the date of the former

as well as of the Saiva revival of which he was the central figure."

(Venkayya 1907, p.228)

Unsung and forgotten are the countless heroes on both sides, their

deeds and brave acts lost in the mist of time, yet heroes they were

nevertheless. Like the knights of the 100-Years' Anglo-French War,

the glorious warriors of the 100-Years' Maratha-Tamil War fought

and died for their homelands, strengthening these nations' foundations

with their blood and bones.

This

100-year Maratha-Tamil war had far-reaching consequences, leading

to the exhaustion of both the Maratha and Dravidian states and sapping

their vitality. These states started to decline after the war. Ultimately,

both the Calukya and Pallava states disappeared from history.

3.4.

Modern-Day Pallavas :

After the Pallava Empire was annexed by the Chola Empire, the Pallavas

merged into the Tamil population :

"The Pallavas of the Tamil country seem to have taken service

under the Colas after the Ganga-Pallavas were conquered by Aditya

about the end of the 9th century AD. Karunakara Tondaiman, who,

according to the Tamil poem Kalingattu-Parani led the expedition

against Kalinga during the reign of Kulottunga I. (AD 1070 to about

AD 1118), was a Pallava and was the lord of Vandai, ie. Vandalur

in the Chingleput District. Among the vassals of Vikrama-Cola mentioned

in the Vikkirama-Solan-ula, the Tondaiman figures first." (Venkayya

1907, p.241)

The Pudukkottai royal family is apparently descended from the ancient

Pallavas :

"In a Tanjore inscription belonging to a later period, the

name Tondaiman is applied to a local chief named Samantanarayana,

who granted to Brahmanas a portion of the village of Karundittaigudi,

the modern Karattattangudi. Thus the name Tondaiman actually travelled

from the Pallava into the Cola country. There is therefore reason

to suppose that the Tondaiman of Pudukkottai, who bears the title

Pallava Raja, is descended from the Pallavas, who form the subject

of this paper." (Venkayya 1907, p.242)

In addition to the royal family of Pudukkottai, other groups are

also probably descended from the Pallavas, such as the Reddis of

Andhra and some of the Kshatriya and Vaishya castes of northern

Tamil Nadu:

"We now have to examine if there are any Pallavas in our midst

beyond the royal family of Pudukkottai. The Pallavas are believed

to be identical with the Kurumbas, of whom the Kurumbar of the Tamil

country and the Kurubas of the Kanarese districts and of the Mysore

State may be taken as the living representatives. The (p.243) kings

of the Vijayanagara dynasty are also supposed to have been Kurubas.

In one of the inscriptions of the Tanjore temple belonging to the

11th century, a certain Velan Adittan is called Pirantaka-Pallavaraiyan,

meaning "the chief of the Pallavas of Parantaka." Sekkilar,

the author of the Tamil Periyapuranam, was a Vellala by caste and

got from his patron, the Cola king Anapaya, the title Uttamasola-Pallavarayan,

meaning "the chief of the Pallavas of Uttamasola." Uttamasola

and Parantaka are titles of Cola kings and the word Pallava seems

to be used in both of the titles as an equivalent of Vellala, or

the caste of agriculturalists to which both of them belonged. In

the Telugu country, too, some of the Reddis who belonged to the

fourth or cultivating caste, called themselves Pallava-Trinetra

and Pallavaditya. Sir Walter Elliot has told us that Pallavaraja

is one of the thirty gotras of the true Tamil-speaking Vellalas

of Madura, Tanjore and Arcot. It is borne by the Cola Vellalas inhabiting

the valley of the Kaveri, in Tanjore, who lay claim to the first

rank. All these facts taken together seem to show that there was

some sort of connection between the cultivating caste and the Pallavas

in the Tamil as well as in the Telugu country. The available evidence

is, however, not sufficient to formulate the nature of this connection.

But it may tentatively be supposed that some of the Pallavas settled

down as cultivators soon after all traces of their sovereignty disappeared.

The other sections of the agricultural class were probably proud

of their association and considered it an honour to be looked uon

as Pallavas." (Venkayya 1907, p.242-243).

4-

Iranian Origin of Dravidian Architecture and Contribution to Dravidian

Civilization :

4.1.

Iranic Origin of Dravidian Architecture :

The Pallava foundations for Dravidian architecture is universally

accepted by scholars. For instance, a standard textbook on World

Architecture states, "Mahabalipuram, the five temples (rathas),

Pallava (7th century AD), are embryonic models of later Dravidian,

or Southern, temple styles." (Holberton, p.55). Confirming

this view, the Encyclopedia Britannica notes :

"The home of the South Indian style, sometimes called the Dravida

style, appears to be the modern state of Tamil Nadu ... The early

phase, which, broadly speaking, coincided with the political supremacy

fo the Pallava dynasty (c.650-893), is best represented by the important

monuments at Mahabalipuram." (Enc.Brit., Vol.27, p.767)

Suthanthiran summarises the views of various eminent scholars :

"The prototypes of later developed Kopurams are found in the

Pallava period. There are different views regarding the proto-types.

Heinrich Zimmer was of the view that the Pimaratam is the earliest

prototype of the Kopurams. Raghavendra Rao says that the finished

oblong plan and the two storeyed waggon roof of Kanesaratam is the

prototype of all South Indian Kopurams ... A.H. Longhurst says that

the Kailasanatha temple entrance Tavaracalai is the proto-type of

all later Kopurams." (Suthanthiran 1989, p.30)

Venkayya agrees with the Pallavite origin of Dravidian architecture

:

"We now enter into a period of Pallava history for which the

records are more numerous. The facts available for this period are

definite and the chronology is not altogether a field of conjecture

and doubt. The earliest stone monuments of Southern India belong

to this period. In fact, the foundations of Dravidian architecture

were laid by the earlier kings of this series.5 (footnote 5: The

monolithic caves of the Tamil country were excavated by the Pallava

king Mahendravarman I. The rathas at the Sevan Pagodas probably

come next. The temples of Kaliesanetha and Vaikuntha-Perumal at

Kañcipuram and the Shore temple at the Sevan Pagodas have

probably to be taken as later developments of Pallava architecture.)"

(Venkayya 1907, p.226)

Fig.5:

Stupendous Granite Kailasanatha temple (formerly Rajasimhesvara),

Tamil Nadu, view from NW, c.695-722 AD. Central shrine built by

Rajasimha (Venkayya 1907, p.230). Note the Iranic vaulted-barrel

cupola similar to Sassanian arch at Ctesiphon and the Babylonian-style

step-pyramid tower or "Shikara". Longhurst holds that

the Kailasanatha temple entrance is the proto-type of all later

Gopurams.

(Image courtesy Dr. Vandana Sinha, American Institute of Indian

Studies, Gurgaon)

One

of the gems of Pallava architecture is the Kailashanatha temple,

which was also known as Rajasimha-Pallavesvara in ancient times

(Venkayya 1907, p.234, footnote 3).

The

pyramid-shaped tower or Shikara of the Kailashanatha temple is strangely

similar to Babylonian step-pyramids. Babylonia was an integral part

of the Parthian empire. While such innovations could have been due

to independant innovation, it is more likely that the Pallavas were

emulating Babylonian prototypes during the construction of Kailasanatha.

Fig.6: Pancha-ratha Pallava Temple at Mamallapuram, Tamil Nadu.

Note the Saka-Buddhist vaulted-barrell cupola on central building.

(Image by Stewart Lane Ellington)

The Pancha-ratha Pallava temple at Mamallapuram consists of five

temples, one having a Saka-Buddhist cupola, one an Egyptian-style

pyramid, and three having ziggurat-shaped roofs reminiscent of Sumer

and Babylon (cf. Fig.6). This combination of designs is unlikely

to have been independantly invented without external stimulus. These

influences could only have come via Iran and the Pallavas, for the

Parthians ruled over Assyria and Babylonia.

4.2.

Spread of Buddhism :

The Pallavas played a major role in propagating the religion of

Buddhism. Buddha was known as Sakya-muni, Prakrit for "Lord

of the Scythians", and was an Iranian. Thus, there is little

surprise when we find Pallavas being the most ardent propagators

of Buddhism: "The sect of Buddhism preached in China by Buddha

Varman, a Pallava Prince of Kanchi came to be known as Zen Buddhism

and it spread later to Japan and other places." (Damodaran

1980, p.70). In other words, Zen Buddhism, like its parent faith

of Buddhism, was founded by an Iranian, Buddha Varman.

4.3.

Dravidian Shaivism :

As noted above, the Pallavas rapidly adopted the indigenous Dravidian

religion of Shaivism, and became staunch propagators of the faith.

Scores of Shiva temples constructed by the Pallavas remain. While

the Pallavas, like the Achaemenids and Parthians, were religiously

tolerant, the devotion of some Pallava kings to Shaivism went so

far that they went to the extent of demolishing Jain temples:

"According to the Periyapuranam, the saint Tirunavukkarasar

(also called Appar), and elder contemporary of Tiruñanasambandar,

was first persecuted and subsequently patronised by a Pallava king

who is said to have demolished the Jaina monastery at Pataliputtiram

and built a temple of Siva called Gunadaraviccaram." (Venkayya

1907, p.235)

By and large, however, the primordial tolerance of Dravidian Shaivism

manifested itself, absorbing the other faiths in due course of time.

5- Refutation of Rival Theories on Origin of Parthians :

Ayyar

has summed up the various non-Parthian theories as follows :

"Thus some scholars considered the Pallavas as of Chola-Naga

origin 2, [2. Ind.Ant. Vol. LII, pp.75-80.] indigenous to the southern

part of the Peninsula and Ceylon and having nothing to do with Western

Indian and Persia, while others placed their original home in the

Andhra country between the rivers Krishna and Godavari; yet others

connected them with the Maharashtra Aryans 3 [3. C.V.Vaidya: History

of Mediaeval India, Vol.1, p.281.] and the Imperial Vakatakas 4

[4.] J.B.O.R.S., 1933, p.180ff.]" (Ayyar 1945, p.11)

We now turn to the three theories, namely Chola-Naga, Andhra and

Maharashtra Aryan origins.

5.1.

Refutation of the Maharashtrian and Vakataka Origin :

The surviving sculptures in Tamil Nadu depict Pallavas as tall and

dolichocephalic (long-headed) (Fig.3), while the Marathas are short-statured

and brachycephalic (round-headed). Moreover, the Pallavas were Shaivites,

as opposed to the Maharastrians, who were adherents of the Vaishnavite

religion. Further, the Pallavas waged the brutal 100-year Maratha-Tamil

war against the Maratha Chalukyas. Had the Pallavas been Maharashtrians,

it is unlikely the conflict would have been so prolonged and of

such intensity. Thus, the Pallavas were almost certainly not of

Maharastrian origin. The slight Maharastrian influence amongst Pallavas

is to be attributed to their migration through Maharashtra on their

way from Persia to Tamil Nadu.

5.2.

Refutation of alleged Vedic Origin :

It is sometimes asserted that the Pallavas were of Vedic origin.

However, the Vedic and Puranic evidence itself contradicts this

view:

"The word Pallava is apparently the Sanskrit form of the tribal

name Pahlava or Pahlava of the Puranas. The Pahlavas are described

as a northern or north-western tribe1 (footnote 1: In chapter 9

of the Bhismaparvan of the Mahabharata, the Pahlavas are mentioned

among the barbarians (mleccha-jatayah)) whose territory lay somewhere

between the river Indus and Persia." (Venkayya 1907, p.217)

Furthermore,

"In the Harivamsa 4 (footnote 4: XIV. verses 15 to 19) the

Pahnavas5 (footnote 5: In the Ramayana (I.55, verse 18) the Pahlavas

are said to have emanated from the bellowing of the miraculous cow

Nandini, which belonged to the sage Vasistha.) are said to have

been Ksatriyas originally, but become degraded in later times. They

are mentioned here along with the Sakas, Yavanas and Kambojas and

their chief characteristic was the beard 6 (footnote 6: The beards

of the Westerns (ie. the Yavanas), are also mentioned by Kalidasa

in his Raghuvamsa, IV, 63) which Sagara permitted them to wear.

In the Visnu Purana, the Yavanas, Pahlavas and Kambhojas are said

to have been originally Ksatriya tribes who became degraded by their

separation from Brahmana and their institutions.7 (footnote 7: Muir's

Sanskrit Texts, Vol.II, p.259, and Ind.Ant. Vol.IV, p.166). In Manu,

the Pahlavas are mentioned along with the Pundrakas, Dravidas, Kambojas,

Yavanas, Sakas and other allied tribes. These were all Ksatriyas

originally, but gradually became degraded by their omission of the

sacred rites and transgressing the authority of the Brahmanas."

(Venkayya 1907, p.217)

Had the Pallavas been of Vedic origin, they would not be cursed

in this manner in the Brahmanic scripture. Moreover, the Pallavas

did not practice the custom of Vedic human sacrifice (purushamedha

or naramedha) and horse sacrifice (asvamedha). Nor did they permit

sati (widow-burning) or bride-burning. The Vedic and Brahmanic caste

system was also not supported. Also, the Pallavas in their earliest

times promoted Prakrit and not Sanskrit. Thus Venkayya notes, "The

earliest known records of the Pallavas are three Prakrt copper-plate

charters, viz. (1) the Mayidavolu plates of Sivaskandavarman, (2)

the Hirehadagalli plates of the same king and (3) the British Museum

plates of Carudevi." (Venkayya 1907, p.222) These facts disprove

the Vedic origin of the Pallavas.

5.3.

Refutation of the Dravidian Origin :

That the Pallavas were not Dravidians is evidenced from the fact

that their migration can be clearly traced via copper-plate grants

as being from the Telugu to the Tamil country. The Pallavas initially

promoted Prakrit, which also goes against the proposed Andhra origin

of Pallavas. Had they been Andhras, they would no doubt have propagated

the proto-Telugu Dravidian dialect.

In

further opposition to the Dravidian origin of Pallavas, Venkayya

has fittingly asked why the Andhras should have adopted a name which

would lead to them being confused with the Pahlavas of Persia.

"Why the indigenous tribe which was formed in the Godavari

delta called itself Pallava, a name which would lead to their being

mistaken for being Palhavas of Western India is a question which,

to my mind, must be satisfactorily answered before the theory of

indigenous origin can be accepted." (Venkayya 1907, p.219,

footnote 5)

However, the Pallavas rapidly adopted the indigenous Dravidian religion

of Shaivism and propagated it, just as the Germanist Lombards accepted

the Roman Catholicism of their Latin Italian subjects. That the

Pallavas were able to flourish in Dravidia is a testimony to Dravidian

tolerance and open-mindedness, a rare characteristic in those days.

The

remaining rival theories on the origins of the Pallavas having been

undermined, the Parthian origin of the Pallavas remains as the sole

logical alternative.

6- Consequences and Conclusion :

The

Parthian origin of the Pallavas was eagerly adopted by virtually

all schools of Dravidologists from the very beginning, Formerly,

Indo-European influence in Dravidian had been attributed solely

to Sanskrit. Anti-Sanskrit Dravidianists welcomed the Iranic origin

of Pallavas as it decreased the Sanskrit proportion in the Indo-European

component of Dravidian civilization. Indeed, certain votaries of

this school believe that Iranic influence in Dravidian is more important

than that of Sanskrit, a view which would no doubt make Iranists

proud. Dravidianist evangelists have in their turn used the Pallava

example to demand that the Tamil Brahmins adopt Dravidian culture.

Their chief argument is that, if the Pallavas from distant Persia

could so eagerly adopt Dravidian civilization, then why couldn't

the local Tamil Brahmins? Multiculturalist Dravidianists, meanwhile,

upheld the Pallavas as an example of ancient Dravidian tolerance

and multi-culturalism. The South Indian Brahminist school, which

is also largely multiculturalist (often miscalled `secularist')

in character, has largely followed this path as well. The political

use - and abuse - of history goes on.

The

Parthian origin of Pallavas also provides an explanation for the

presence of tall, fair-skinned members of non-Brahmin castes in

Tamil Nadu and other Dravidian states. Formerly attacked as mixed-caste,

part-Brahmin, offspring, it is observed that such persons are at

present claiming a Pallava-Parthian origin instead. This is certainly

true of certain Cholas, Vellalas and Reddis. Especially in case

of those fair individuals who are long-headed, a Pallavite origin

is more plausible than a mixed-Brahmin one, for the South Indian

Brahmins are generally round-heads. The Parthian theory of the origin

of Pallavas has thus helped a large number of people to be rehabilitated

in Dravidian society.

It

is hoped that Iranists will be inspired by this work to carry out

further research on the achievements of the enterprising Pallavas

in Dravidia, and bring to light the full scale of Iranic influence

in Dravidian civilization.

Appendix:

Extracts from "A New Link between the Indo-Parthians and the

Pallavas of Kanchi"

As

Ayyar's 1945 paper is difficult to obtain both in India and abroad,

I am reproducing extracts below for reference purposes.

| Journal

of Indian History |

J.Ind.Hist. Vol.XXIV,

Parts 1 & 2, April & August 1945, Serial Nos. 70 &

71, p.11-16;

Ananda Press, Madras. |

|

"A

New Link between the Indo-Parthians and the Pallavas of

Kanchi" *

By: V.Venkatasubba Ayyar, Ootacamund

"Though Archaeology, Numismatics and Epigraphy, each by

itself, are great assets to the Historian, they rarely combine

to assist him in any intricate problem of history. Sometimes

the evidence adduced by these remain inexplicable when considered

separately, but they gain a new meaning and assume fresh

importance when collated together. Such may be said to be

the case of some new evidence that is now advanced on what

may be called the `Indo-Parthian Origin' of the Pallavas

of Kanchi.

It was my father the late Rai Bahadur Venkayya who first

traced the origin of the Pallavas of Kañchi to the Pahlavas mentioned

in the Mahabharata and the Puranas where

they are classified as foreigners outside the pale of Aryan

society 1. He thus postulated that they

were a northern tribe of Parthian origin with their original

home in Iran.This theory was first accepted by scholars,

but discarded by later writers as resting wholly on doubtful

philological resemblance of the words Pahlava and Pallava.

Several arguments against the `foreign origin' were cited,

such as the absence of any reference to Pallava migration

in copper-plate grants, the more possible identity of the

Pallavas with the indigenous Tondaiyar and the Kadavar,

and the testimony of the poet Rajasekhara of about the 10th

century AD who refers to two distinct Pallava kingdoms,

one in the south and the other in the north-west. Thus some

scholars considered the Pallavas as of Chola-Naga origin 2,

indigenous to the southern part of the Peninsula and Ceylon

and having nothing to do with Western Indian and Persia,

while others placed their original home in the Andhra country

between the rivers Krishna and Godavari; yet others connected

them with the Maharashtra Aryans 3 and

the Imperial Vakatakas 4

*

A paper sent to the Eleventh All-India Oriental Conference,

Hyderabad (1941)

1. Archl Sur. Rep. for 1906-7, pp.217ff.

2. Ind.Ant. Vol. LII, pp.75-80.

3. C.V.Vaidya: History of Mediaeval India,

Vol.1, p.281.

4. J.B.O.R.S., 1933, p.180ff.

|

|

p.12

The question of the origin of the Pahlavas may, therefore

be said not to have yet been satisfactorily settled. Opinion

seems to have now swung back, and recently two authors 5,

after examining the arguments for the `indigenous theory',

were inclined to advocate the `foreign origin' first propounded

by Venkayya. A very important evidence

that is helpful in settling this question is now available.

It is found in one of the explanatory labels to the sculptures

decorating the walls of the verandah round the central shrine

of the Vaikuntha-Perumal temple 6 at

Conjeevaram. This unique and valuable epigraph narrates

how on the death of Paramesvara-Pottaraiyar of the Pallava

family without any issue, a deputation of ministers waited

on Hiranyavarman of a collateral line and requested him

to grant themn a ruler for the vacant throne. Hiranyavarman

thereupon consulted his nobles (kullamallar) and

then his four sons, and enquired who among them would accept

the sovereignty. All of them declined the offer except the

youngest prince, Paramesvaravarman, aged twelve years. Thereupon

the deputation offered, probably to Hiranyavarman as the

chief of the family, the makuta resembling

an Elephant's Head which they had brought for the sovereign-elect.

The passage 7 reads:

(This

is) the scene where Hiranyavarmma-Maharaja was seized

with fear8(on) hearing Tarandikondaposar say

`Hear (what thy) elderly servants submit. This (ie. the

object brought) is not an elephant's head, but (only)

they son's makuta

5.

Mr. K.R.Subrahmanyam in his `Buddhist Remains

in Andhra', p.73ff and Mr. P.T.S. Iyengar in his `History

of the Tamils', p.329.

6. These Historical sculptures form the subject of a Memoir

(no.63) by the late Dr. Minakshi issued recently by the

Arch. Sur. of India.

7. The inscription is published in S.I.I. Vol.IV, No.135

but the reading there is not quite reliable. A revised

reading is given by the late Mr. A.S.Ramanatha Ayyar in

Memoir No.63 noticed above.

8. Ramanatha Ayyar (Memoir, No.63) reads here `biti-[vi]du'

in the sense `abandoned fear' but Padu is clear on the

stone. My colleague Mr. G.V.Srinivasa Rao also favours

the reading padu as the fear is at the thought of the

son's impending departure and separation (pirivin santapam)

mentioned later on and not really at seeing the makuta

resembling the elephant's head. Dr. Minakshi has missed

this implication and ascribes the fear either to Hiranyavarma's

ignorance of court customs or to his old age and failure

of vision.

|

|

p.13

The passage previous to the one just cited is damaged, but

it also refers to `the elephant's head' brought by the deputation.

These two passages clearly indicate that the makuta presented

to the king-elect was really shaped like an elephant's scalp.

Appropriately enough in the sculptural representation 9 above

this label can be seen standing three persons, of whom one

in the centre is carrying an object like the elephant's

scalp. This object must be the crown that Nandivarman had

to wear on ceremonial occasions. Excepting this single

sculptural representation of the elephant's scalp and the

epigraphical explanation of it just cited, no other reference

to such a head-dress has so far been found in Pallava sculptures

and in fact, in the whole range of Indian Art. But a study

of the Greek coins of the successors of Alexander the Great

throws light on this custom. The elephant's

scalp 10 as a motif of head-dress is

found for Alexander in the early coins of his governors,

Ptolemy I of Egypt and Seleucus of Babylon. To the numismatists

this headgear was a puzzle and they explained it variously,

as representing the conquest by Alexander of India, the

land of the elephant par excellence, as a

mere symbol of power, as a mark of deification, as a mint-mark

specially referring to the elephant-god of Kapisa 11 etc.

Alexander 12 did not adopt the emblem

of elephant's scalp himself on his coins, but this symbol

served as the iconographical expression of the monarchical

principle to some of his successors. When after the death

of their master 13, his generals Ptolemy

I and Seleucus, established themselves as kings, the former

in Egypt and the

9.

This panel is very much damaged.

10. The use of scalp as a device on coins was first

started in the island of Samos belonging to the Ionian

Greeks. Demoteles or his successor

at Samos before the end of the 7th century caused to be

struck the first official coins of Samos with the lion's

scalp. This was adopted as the chief Samian device and

it continued to decorate the city's coinage until she

became merged in the Roman Province of Asia (Greek

Coins: Seltman, p.31). But the elephant itself was

used as a device in the coins of Antimachos Theos, Heliokles,

Lysias, Antialkidas, Archebios, Apollodotus, Soter, Menander,

Zoilos, Maues, Azes, Ayileses and Zeioinises (Ind.

Hist. Quart., Vol. XIV, p.301)

11. The tutelary deity of the city of Kapisa is supposed

to be Indra accompanied by an elephant (Ind. Hist.

Quart., Vol.XIV, p.299). The kingdom of Kapisa formed

the connecting link between Bactria and India. See Greeks

in Bactria and India: W.W.Tarn, p.138.

12. In early times it was deemed sacrilegous to put the

portrait of a human being on coins. But Alexander introduced

his portrait on his issues in the guise of Zeus or Heracles

and the figure can be recognised on coins with absolute

certainty. After his death this figure came to be used

as a type on coins and he was even raised to the rank

of divinity.

13. Coins were issued in Alexander's name long after his

death. Such types were minted by many cities in Asia Minor

and they continued to be struck long after even his empire

had crumbled into small states. In fact, Alexander's coinage

was among the most lasting of his institutions.

|

|

p.14

latter in Babylon, they issued their early coins with the

figure of Alexander wearing the elephant's scalp. Rao Bahadur

K.N.Dikshit has noticed a coin of Andragoras a satrap of

Parthia under Alexander the Great, bearing on the obverse

the head of Alexander as on the coins of Ptolemy I of Egypt 14.

Agathocles the tyrant of Syracuse who concluded an alliance

with Ptolemy I issued a similar type of coin with this head-gear,

in Africa 15. This symbol was also adopted

by Antiochus IV 16, Alexander II 17 and

Lysias 18, but the best and most artistic

specimen of the elephant-scalp type of coin is that of the

Bactrian king Demetrius II who re-conquered the countries

of the Indus valley which had been occupied by Alexander

the Great, but subsequently surrendered by his successor

Seleucus I to Chandragupta. Demetrius, known as the `first

king of Bactria and of India' is here represented with a

helmet resembling an elephant's head complete with proboscis

and tusk, and it is surmised that he was conspicuously imitating

Alexander whom he regarded as his ancestor and ideal.

The tradition behind the adoption of this symbol is not

clear. Some of the kings like Potlemy who used it had no

connection with India, and Seleucus had even bartered his

Indian Province for 500 war-elephants. It is, therefore,

supposed that the use of this symbol for Alexander represented

the utmost extent of Power 19, for both

Ptolemy I and Seleucus who first adopted it `had every object

in representing themselves as the successors of the man

who had reached the summit of human greatness' 20.

It is however just possible that this motif is reminiscent

of Alexander's connection with India.

The coincidence in the use of this peculiar head-dress by

the successors of Alexander in the centuries BC and by the

Pallava ruler Nandivarman in the 8th century AD is of more

than ordinary interest. In the Vaikuntha-Perumal temple

inscription mentioned above, Tarndikonda-Posar, the vriddhagamikar (ie.

aged soothsayer), is stated to have prophesied that Nandivarman

would become a Chakravartti ie. the king of kings 21 (ivan

Chakravartti avan). The consecration (abhisheka) ceremony

14. Ind.

Ant. Vol.XLVIII, pp.120-121.

15. Historical Greek Coins: G.F.Hill, No.65.

16. The Greeks in Bactria and India: Tarn,

p.189.

17. The Seleucid Kings of Syria: P.Gardner,

p.26, No.61.

18. Greek and Scythic Kings of Bactria and India:

P.Gardner, Pl.X, 6 and Indo-Greek Coins: R.B.

Whitehead, Vol.I, p.30.

19. In the royal consecration called Rajasuya, the king

has to step on a tiger skin as a symbol of acquisition

of power.

20. The Greeks in Bactria and India: W.W.Tarn,

p.131.

21. In this connection the adoption of the imperial title

`king of kings' by the Saka and Pahlava suzerains is worthy

of notice.

|

|

p.15

of this king is stated to have been immediately celebrated

when he was still an unmarried 22 prince

of only twelve years 23. It is not, however,

clear from the inscription whether this ceremony was in

the nature of mere nomination to the throne or of actual

coronation (mudi-suttudal).

It is worthy of note that in the sculptures of the Vaikuntha-Perumal

temple, the elephant's scalp is not found as a head-dress

of the Pallava kings. Its use by Nandivarman alone may be

said to signify his elevation to regal power, as in the

case of Ptolemy I and Seleucus who first adopted this symbol

on their coins when they established themselves as kings

from their position as Viceroys, after the death of their

master Alexander the Great. Ernest Hersfeld observes

in connection with Kushano-Sasanian coins, that the helmet

surmounted by an animal's head such as that of a lion, a

horse, an eagle, etc. is the exclusive emblem of the members

of the royal family next to the throne.24

The practice of wearing this elephant's scalp observed in

common may therefore be considered as establishing a strong

link between the Pahlavas and the Pallavas.

This headgear has not so far been found among other Hindu

rulers of India. Why, then should the Pallavas alone adopt

it? The early Pallavas are not celebrated in Tamil literature,

they are not classed among the Tamil speaking people and

they are also not known to have had any matrimonial connection

with the Tamil kings. Their culture was alien to the land

of their settlement. The evidence now adduced is thus valuable

as emphasising this point and indicating their original

habitat beyond the borders of India. This evidence may be

said to gain in importance when considered with other circumstances

such as the similarity of the name Pallava to the form Pahlava 25,

the reference to the rule of the Pahlava governor named

Suvisaka in Anarta (ie. the district round the modern Dvaraka)

and Surashtra 26, the tradition of marriage

alliance with the Nagas common to both the Indo-Scythians

and the Pallavas, the reference made by Ptolemy the Geographer

to the Parthian princes as constantly changing their abode

by driving each other

22.

The Rajyabhisheka ceremony, as laid down in the Sastras,

required the presence of the chief queen. Cf. Harsha of

Kanaouj; it is stated that he was not married when he

succeeded to the throne and that his coronation was postponed

on this account (IHQ, Vol.XII, p.142).

23. Dr. Jayaswal has tried to show that the minimum age

for coronation of a king must be 25 years and he cites

instances of the coronations of Asoka and Kharavela who

had to pass a considerable period after the demise of

their predecessors before they could ascend the throne

(Hindu Polity, p.52; Ind. Hist. Quart.,

Vol. XII, p.142).

24. Memoir of the Arch. Sur. of India, No.38,

p.21.

25. History of Indian Literature: Weber,

p.188, note 201.

26. Ep.Ind., Vol. VIII, p.41.

|

|

p.16

out and the possibility of tracing the different stages

of the Pahlava migration through Kathiawad, Malwa, United

Provinces 27, Dhanakada, and finally to

Kañchi on the east coast. By

the time the Pahlavas settled down at Kañchi they

were so Hinduised and merged into the society of their new

home that they came to be regarded as Kshatriyas 28 belonging

to the Bharadwajagotra, observing Asvamedha and other rituals

of the Hindus. The new link now furnished thus strengthens

the statement made by Venkayya that `the Pallavas of

Kañchipuram must have come originally from Persia,

though the interval of time which must have elapsed since

they left Persia must be several centuries' 29."

27.

Dr. Fleet finds in the Pahladpur inscription of Sisupala

a possible reference to the Pallavas of Northern India: Gupta

Ins. Fleet, p.250.

28. In the Harivamsa and the Vishnupurana,

the Pahlavas are classed as Kshatriyas.

29. Arch. Sur. Rep. for 1906-7, p.219.

|

Acknowledgements

:

The author would like to thank Prof. Shireen Moosavi and Prof. Irfan

Habib (Aligarh) for their kind assistance with references. The author

is also very grateful to Prof. P. Oktor Skjærvø and

Prof. Michael Witzel (Harvard) for kindly sending important research

material. Many thanks to Fatema Soudavar Farmanfarmaian for fruitful

discussions, and to The Iranian for publishing this paper.

The

author gratefully thanks Michael D. Gunther, art-and-archaeology.com;

Dr. Vandana Sinha, American Institute of Indian Studies, Gurgaon,

indiastudies.org; and Stewart Lane Ellington, stewellington.com

for permission to reproduce their wonderful images in this paper.

References

:

Ayyar

1945: "A New Link between the Indo-Parthians and the Pallavas

of Kanchi" by V. Venkatasubba Ayyar, Ootacamund, Journal of

Indian History, Vol.XXIV, Parts 1 & 2 (April & August 1945)

Serial Nos. 70 & 71, p.11-16; Ananda Press, Madras.

Damodaran

1980: "Contribution of the Tamils to World Culture", G.R.Damodaran,

J.Tamil Studies, vol.18 (Dec. 1980) pp.69-76.

Derakhshani

1999: "Die Arier in den nahÎstlichen Quellen des 3. und

2. Jahrtausends v.Chr." by Jahanshah Derakhshani, International

Publications of Iranian Studies, http://www.int-pub-iran.com, 2.Auflage,

1999; ISBN 964-90368-6-5.

Holberton

19??: "The World of Architecture" Paul Holberton, WHSmith,

Michael Beazley Publishers, 14-15 Manette St, London W1V 5LB.

Minakshi

1977: "Administration and Social Life under the Pallavas",

by Dr. G.Minakshi, University of Madras, Madras, 1977.

Nair

1977: "The Problem of Dravidian Origins - A Linguistic, Anthropological

and Archaeological Approach", by T.Balakrishnan Nair, University

of Madras, Madras, 1977.

Skjærvø

1995: "The Avesta as source for the early history of the Iranians",

P.Oktor Skjærvø, in `The Indo-Aryans of Ancient South

Asia', ed. George Erdosy, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 1995, pp.155-176.

Spooner

1915: "The Zoroastrian Period of Indian History" by D.B.Spooner,

J.of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, 1915,

p.64-89 (Pt.I); p.405-455 (Pt.II).

Suthanthiran

1989: "Evolution of Gopura in Temple Architecture of Tamil

Nadu", by A. Veluswamy Suthanthiran, J.Tamil Studies, vol.35

(June 1989) pp.28-38.

Venkayya

1907: "Annual Report 1906-7", Archaeological Survey of

India, "The Pallavas", by V.Venkayya, p.217-243; reprint

Swati Publications, Delhi.

Waddell

1929: "The Makers of Civilization in Race and History",

by L.A. Waddell, 1929, reprint S.Chand & Company, P.O.Box No.

5733, Ram Nagar, 7361, New Delhi-110055, 1986, schand@vsnl.com,

schandgroup.com.

Witzel

2001: "Autochthonous Aryans? The Evidence from Old Indian and

Iranian Texts," by Michael Witzel, El.J. of Vedic Studies 7-3

(2001), p.1-115 (people.fas.harvard.edu/~witzel/).

Source

:

http://www.iranchamber.com/

history/articles/india_parthian_

colony1.php

http://www.iranchamber.com/

history/articles/india_parthian_

colony2.php