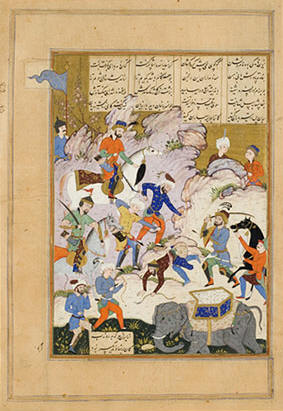

| THE EPIC The Epic :

The Shahnameh, Book of Kings, is an epic composed by the Iranian poet Hakim Abul-Qasim Mansur (later known as Ferdowsi Tusi), and completed around 1010 CE.

[Ferdowsi means 'from paradise', and is derived from the name Ferdous (cf. Avestan pairi-daeza, later para-diz then par-des or par-dos, arabized to fer-dos). Tusi means 'from Tus'. In the poet's case, the name Ferdowsi Tusi became a name and a title: The Tusi Poet from Paradise.]

The epic chronicles the legends and histories of Iranian (Aryan) kings from primordial times to the Arab conquest of Iran in the 7th century CE, in three successive stages: the mythical, the heroic or legendary, and the historic.

Ferdowsi began the composition of the Shahnameh's approximately 100,000 lines as 50,000* couplets /distiches (bayts) each consisting of two hemistichs (misra), 62 stories and 990 chapters, a work several times the length of Homer's Iliad, in 977 CE, when eastern Iran was under Samanid rule. The Samanids had Tajik-Aryan affiliation and were sympathetic to preserving Aryan heritage.

[*Note: the number of couplets composed by Ferdowsi for the Shahnameh is stated as 60,000 in a number of sources. This is incorrect as some manuscripts have added verses.]

It took Ferdowsi thirty three years to complete his epic, by which time the rule of eastern Iran had passed to the Turkoman Ghaznavids (who based themselves in the north-eastern province of Khorasan with Ghazni as their capital).

The Shahnameh was written in classical Persian when the language was emerging from its Middle Persian Pahlavi roots, and at a time when Arabic was the favoured language of literature. As such, Ferdowsi is seen as a national Iranian hero who re-ignited pride in Iranian culture and literature, and who established the Persian language as a language of beauty and sophistication. Ferdowsi wrote: "the Persian language is revived by this work."

The Poet Ferdowsi (c. 935 to 941 - 1020 to 1026 CE) :

Facade to Ferdowsi's Mausoleum in Tus The earliest and perhaps most reliable account of Ferdowsi's life comes from Nezami-ye Aruzi, a 12th-century poet who visited Tus in 1116 or 1117 to collect information about Ferdowsi's life. According to Nezami-ye Aruzi, Ferdowsi Tusi was born into a family of landowners near the village of Tus in the Khorasan province of north-eastern Iran. Ferdowsi and his family were called Dehqan, also spelt Dehgan or Dehgan. Dehqan /Dehgan is now thought to mean landed, village settlers, urban and even farmer. However, Dehgan is also a name for the Parsiban, a group of Khorasani with Tajik roots (for further information see the section of Parsiban / Farsiwan in our page on Haroyu, Aria and Herat).

Ferdowsi married at the age of 28 and eight years after his marriage - in order to provide a dowry for his daughter - Ferdowsi started writing the Shahnameh, a project on which he spent some thirty three years of his life.

While Ferdowsi was composing the Shahnameh, Khorasan came under the rule of Sultan Mahmoud, a Turkoman Sunni Muslim and consolidator of the Ghaznavid dynasty. Ferdowsi sought the patronage of the sultan and wrote verses in his praise. The sultan, on the advice from his ministers, gave Ferdowsi an amount far smaller than Ferdowsi had requested and one that Ferdowsi considered insulting. He had a falling out with the sultan and fled to Mazandaran seeking the protection and patronage of the court of the Sepahbad Shahreyar, who, it is said, had lineage from rulers during the Zoroastrian-Sassanian era. In Mazandaran, Ferdowsi wrote a hundred satirical verses about Sultan Mahmoud, verses purchased by his new patron and then expunged from the Shahnameh's manuscript (to keep the peace perhaps). Nevertheless, the verses survived. An example:

Long years this Shahnameh I toiled to complete, That the King might award me some recompense meet, But naught save a heart wrung with grief and despair Did I get from those promises empty as air! Had the sire of the King been some Prince of renown, My forehead would surely have been graced by a crown! Were his mother a lady of high pedigree, In silver and gold I'd have stood to the knee!But, being by birth not a prince but a boor, The praise of the noble he could not endure!Ferdowsi returned to Tus to spend the closing years of his life forlorn. Notwithstanding the lack of royal patronage, he died proud and confident his work would make him immortal.

Language :

If the Shahnameh transliterations this author possesses are correct, Ferdowsi even used the term Parsi and not Farsi to name the Persian language, Farsi being the Arabic version of Parsi.

Writing & Books :

Oral Tradition :

[*Note:

The name pahlavan is linked to Pahlavi, the Middle Persian writing

system used in many Zoroastrian texts and said be native to Parthava

(Parthia), the region that once included Ferdowsi’s birthplace

of Khorasan. Pahlavi came to be known as Parsik, the language of

Pars (later Parsi, then Farsi – Persian written with an Arabic

script).]

Ferdowsi's biographer Nezami-ye Aruzi tells us that Ferdowsi based his work on the Middle Persian Pahlavi work, the Khvatay-Namak (also written Xwaday Namag or Khodai-Nama), a history of the kings of Persia complied under orders of Sassanian king Khosrow (Khusrau) I (531-579 CE). Work on the Khvatay-Namak is said to have continued into the reign of the last Zoroastrian-Sassanian monarch of Iran, Yazdegird III (633-649 CE), when former editions were added to by the Dihkan Daneshvar assisted by several learned mobeds.

The Khvatay-namak was based on information gathered from Zoroastrian priests and the legendary accounts in the Avesta memorized by the priests. The Khvatay-namak could be the work to which Ferdowsi refers when he talks about the paladin who gathered the epic cycles memorized by Zoroastrian priests (archmages, mobeds). While the Khvatay-namak was started during the reign of Khosrow (Khusrau) I, it is reputed to have been updated to include the stories of kings up to the fall of the Sassanian dynasty. There are no known copies of the Khvatay-namak in existence. In his prologue, Ferdowsi stated he needed to move quickly so that he could implement his mission to keep past legends and histories alive - before their imminent destruction.

A possible predecessor to the Khvatay-Namak could be the Chihrdad, one of the destroyed books of the Avesta (known to us because of its listing and description in the Middle Persian Zoroastrian text, the Dinkard 8.13). The text was said to have been a history of humankind from the beginning down to the revelation of Zarathushtra.

Achaemenian Era Book of Kings - Basilikai Diphterai :

If this account of Diodorus is correct, then it appears that there was a written tradition of a Persian/Iranian book of Kings from at least the 5th century BCE and probably much earlier - especially since it was part of an ongoing and ancient tradition.

Daqiqi :

Daqiqi (also Dakiki) wrote about a thousand verses on Zoroastrian history and beliefs before he was murdered by his servant. While outwardly a Muslim, Daqiqi was considered a Zoroastrian sympathizer if not a closet Zoroastrian, a dangerous affiliation in those fanatical times. A verse of Daqiqi reads:

Daqiqi chaar kheslat bar-gozida ast

Translation

:

Daqiqi put the ancient Airanian legends to verse and wrote a thousand and eight verses before he was tragically murdered. These thousand lines are similar in scope and subject matter to the Middle Persian Ayadgar i Zareran, though Daqiqi's source is thought to be the Khvatay Namak (Xwaday-namag). Significantly, Daqiqi had started his Shahnameh, not with the dawn of history, but with the Kayanian King Gushtasp's (Vishtasp's) patronage of Zarathushtra's religion.

Ferdowsi sought out and inserted Daqiqi-e Balkhi's one thousand and eight verses, beginning with the rule of King Gushtasp (Vishtasp), Gushtasp's acceptance of Zarathushtra's message, and ending with Arjasp's attack on Airan after Gushtasp imprisons his son Esfandiar. In a preface to the borrowed verses, Ferdowsi writes that in a dream, Daqiqi exhorted Ferdowsi to use these verses and in addition, to complete the tragic poet's unfinished mission to chronicle Zoroastrian and Aryan heritage.

Ferdowsi undertook his venture at a time when every effort was being made by some zealots to extinguish all memory of Zoroastrian and Aryan tradition. However, Ferdowsi was more circumspect in his approach and not as blatantly pro-Zoroastrian as Daqiqi. Some authors state that Daqiqi's most controversial verses were not included in Ferdowsi's Shahnameh and have been lost.

Other Legends :

[Note: *The lineage of the Siestan heroes was: Garshasp, Nariman, Sam, Zal, Rustam, Sohrab and Barzu.

Ferdowsi's Original Work Lost :

Differences in Shahnameh Copies :

The ad hoc editing by subsequent scribes as well as errors has resulted in every existing manuscript copy being different in content and length - lengths from less than 50,000 to around 60,000 verses. There has consequently been considerable debate among 'experts' as to which version is authentic or authoritative.

Reconstruction of an Authoritative Shahnameh :

One of the first attempts was Mohl’s edition in 7 volumes (Paris, 1838-78) based on 35 manuscripts. Mohl’s edition and French translation were used to author the only complete Shahnameh’s English translation in verse – that by A.G. and E. Warner, (6-10 vols. London, 1905-25).

A ten-volume reconstructed edition was later published in Tehran (1934-35).

Next, a nine-volume edition was published in Moscow by Y. E. Bertel and others (1966-71). The Moscow edition was based, among others, on the British Museum manuscript dated 1276 and a manuscript in Leningrad dated 1333 – both of which were among those considered authoritative by the experts at that time.

In 1987, Dr. Djalal Khaleghi-Motlagh published the first volume of his reconstructed text. Volumes 2 to 5 have subsequently been published (1988-97). Dr. Khaleghi-Motlagh selected fifteen manuscripts on which to base his edition and these manuscripts included the British Museum and Leningrad MSS. According to a review by Dick Davis, Khaleghi-Motlagh now considers the Leningrad manuscript copy to be ghayr-e asli meaning secondary and inauthentic.

English Translations :

Spelling

of the Names :

Ferdowsi - 221,000 (used here), Firdawsi- 130,000, Firdausi - 106,000, Firdousi - 41,200, Firdusi - 38,700, Firdowsi - 6,230, Ferdausi - 5,420, Ferdawsi - 2,020.

Shahnameh - 221,000 (used here), Shahnama - 103,000, "shah nameh" - 28,800, shahname - 25,600, "shah nama" - 9,650, shahnama - 7,860, "shah name" - 5,500, shanameh - 1,980, shaname - 1,860.

Source

: |