| PARMAR DYNASTY Parmars of Malwa :

9th or 10th century CE – 1305 CE :

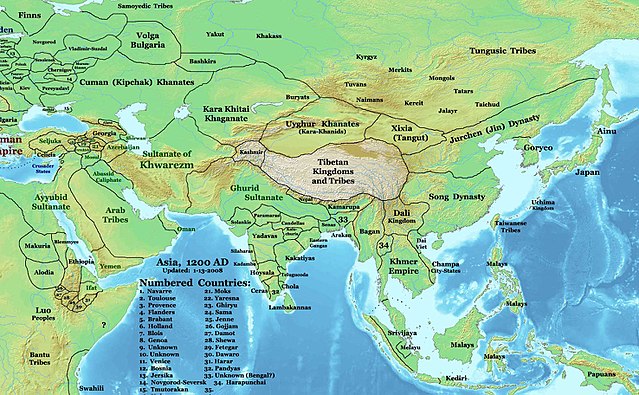

Map of Asia in 1200 CE. Paramara kingdom is shown in central India Capital

: Dhar

• Established : 9th or 10th

century CE

Preceded by

Gurjara-Pratihar

Succeeded by

Delhi Sultanate

Today part of : India

The Parmar dynasty was an Indian dynasty that ruled Malwa and surrounding areas in west-central India between 9th and 14th centuries. The medieval bardic literature classifies them among the Agnivanshi Rajput dynasties.

The dynasty was established in either 9th or 10th century, and its early rulers most probably ruled as vassals of the Rashtrakuts of Manyakhet. The earliest extant Parmar inscriptions, issued by the 10th century ruler Siyaka, have been found in Gujarat. Around 972 CE, Siyaka sacked the Rashtrakut capital Manyakhet, and established the Parmars as a sovereign power. By the time of his successor Munja, the Malwa region in present-day Madhya Pradesh had become the core Parmar territory, with Dhara (now Dhar) as their capital. The dynasty reached its zenith under Munja's nephew Bhoj, whose kingdom extended from Chittor in the north to Konkan in the south, and from the Sabarmati River in the west to Vidisha in the east.

The Parmar power rose and declined several times as a result of their struggles with the Chaulukyas of Gujarat, the Chalukyas of Kalyani, the Kalachuris of Tripuri, Chandelas of Jejakabhukti and other neighbouring kingdoms. The later Parmar rulers moved their capital to Mandapa-Durga (now Mandu) after Dhara was sacked multiple times by their enemies. Mahalakadeva, the last known Parmar king, was defeated and killed by the forces of Alauddin Khalji of Delhi in 1305 CE, although epigraphic evidence suggests that the Parmar rule continued for a few years after his death.

Malwa enjoyed a great level of political and cultural prestige under the Parmars. The Parmars were well known for their patronage to Sanskrit poets and scholars, and Bhoj was himself a renowned scholar. Most of the Parmar kings were Shaivites and commissioned several Shiv temples, although they also patronized Jain scholars.

Origin

:

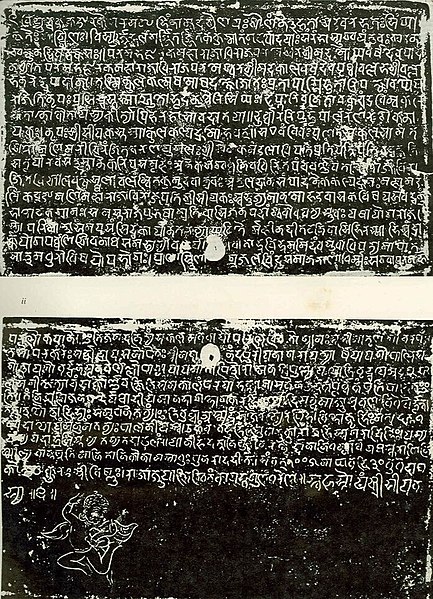

Harsola copper plates The Harsola copper plates (949 CE) issued by the Parmar king Siyaka II mentions a king called Akalavarsha, followed by the expression tasmin kule ("in that family"), and then followed by the name "Vappairaj" (identified with the Parmar king Vakpati I). Based on the identification of "Akalvarsh" (which was a Rashtrakut title) with the Rashtrakut king Krishna III, historian as D. C. Ganguly theorized that the Parmars were descended from the Rashtrakuts. Ganguly tried to find support for his theory in Ain-i-Akbari, whose variation of the Agnikul myth states that a predecessor of the Parmars came to Malwa from Deccan. According to Ain-i-Akbari, Dhanji - a man born from a fire sacrifice - came from Deccan to establish a kingdom in Malwa; when his descendant Putraj died heirless, the nobles established Aditya Ponwar - the ancestor of the Parmars - as the new king. Ganguly also noted Siyaka's successor Munja (Vakpati II) assumed titles such as Amoghvarsh, Sri-vallabh and Prithvi-vallabh: these are distinctively Rashtrakut titles.

However, there is a lacuna before the words tasmin kule ("in that family") in the Harsol inscription, and therefore, Ganguly's suggestion is a pure guess in absence of any concrete evidence. Moreover, even if the Ain-i-Akbari legend is historically accurate, Aditya Ponwar was not a descendant of Dhanji: he was most probably a local magnate rather than a native of Deccan. Critics of Ganguly's theory also argue that the Rashtrakut titles in these inscriptions refer to Parmar rulers, who had assumed these titles to portray themselves as the legitimate successors of the Rashtrakuts in the Malwa region. The Rashtrakuts had similarly adopted the titles such as Prithvi-vallabh, which had been used by the preceding Chalukya rulers. Historian Dasharatha Sharma points out that the Parmars claimed the mythical Agnikul origin by the tenth century: had they really been descendants of the Rashtrakuts, they would not have forgotten their prestitgious royal origin within a generation.

The later Parmar kings claimed to be members of the Agnikul or Agnivansh ("fire clan"). The Agnikul myth of origin, which appears in several of their inscriptions and literary works, goes like this: The sage Vishvamitra forcibly took a wish-granting cow from another sage Vashisth on the Arbud mountain (Mount Abu). Vashisth then conjured a hero from a sacrificial fire pit (agni-kund), who defeated Vishvamitra's enemies and brought back the cow. Vashisth then gave the hero the title Parmar ("enemy killer"). The earliest known source to mention this story is the Nav-sahasank-charit of Padmagupt Parimal, who was a court-poet of the Parmar king Sindhuraj (ca. 997-1010). The legend is not mentioned in earlier Parmar-era inscriptions or literary works. By this time, all the neighbouring dynasties claimed divine or heroic origin, which might have motivated the Parmars to invent a legend of their own.

The later Parmar kings claimed to be members of the Agnikul or Agnivansh ("fire clan"). The Agnikul myth of origin, which appears in several of their inscriptions and literary works, goes like this: The sage Vishvamitra forcibly took a wish-granting cow from another sage Vashisth on the Arbud mountain (Mount Abu). Vashisth then conjured a hero from a sacrificial fire pit (agni-kund), who defeated Vashisth's enemies and brought back the cow. Vashisth then gave the hero the title Parmar ("enemy killer"). The earliest known source to mention this story is the Nav-sahasank-charit of Padmagupt Parimal, who was a court-poet of the Parmar king Sindhuraj (ca. 997-1010). The legend is not mentioned in earlier Parmar-era inscriptions or literary works. By this time, all the neighbouring dynasties claimed divine or heroic origin, which might have motivated the Parmars to invent a legend of their own.

In the later period, the Parmars were categorized as one of the Rajput clans, although the Rajput identity didn't exist during this time. A legend mentioned in a recension of Prithviraj Raso extended their Agnikul legend to describe other dynasties as fire-born Rajputs. The earliest extant copies of Prithviraj Raso do not contain this legend; this version might have been invented by the 16th century poets who wanted to foster Rajput unity against the Mughal emperor Akbar. Some colonial-era historians interpreted this mythical account to suggest a foreign origin for the Parmars. According to this theory, the ancestors of the Parmars and other Agnivanshi Rajputs came to India after the decline of the Gupta Empire around the 5th century CE. They were admitted in the Hindu caste system after performing a fire ritual. However, this theory is weakened by the fact that the legend is not mentioned in the earliest of the Parmar records, and even the earliest Parmar-era account does not mention the other dynasties as Agnivanshi.

Some historians, such as Dashrath Sharma and Pratipal Bhatia, have argued that the Parmars were originally Brahmins from the Vashisth gotra. This theory is based on the fact that Halayudh, who was patronized by Munj, describes the king as "Brahma-Kshtra" in Pingal-Sutra-Vritti. According to Bhatia this expression means that Munja came from a family of Brahmins who became Kshatriyas. In addition, the Patanarayan temple inscription states that the Parmars were of Vashisth gotra, which is a gotra among Brahmins claiming descent from the sage Vashisth. However, historian Arvind K. Singh points out that several other sources point to a Kshatriya ancestry of the dynasty. For example, the 1211 Piplianagar inscription states that the ancestors of the Parmars were "crest-jewel of the Kshatriyas", and the Prabha-vakara-charit mentions that Vakpati was born in the dynasty of a Kshatriya. According to Singh, the expression "Brahma-Kshatriya" refers to a learned Kshatriya.

D. C. Sircar theorized that the dynasty descended from the Malavs. However, there is no evidence of the early Parmar rulers being called Malav; the Parmars began to be called Malavs only after they began ruling the Malwa region.

A Chaulukya-Parmar coin, circa 950-1050 CE. Stylized rendition of Chavda dynasty coins: Indo-Sassanian style bust right; pellets and ornaments around / Stylised fire altar; pellets around

Coin of the Parmar king Naravarman, circa 1094-1133. Goddess Lakshmi seated facing / Devanagari legend

Coin of the Parmar prince Jagdev, 12th-13th centuries CE Original homeland :

Places in Gujarat where the earliest Parmar inscriptions (of Siyaka II) have been discovered Based on the Agnikul legend, some scholars such as C. V. Vaidya and V. A. Smith speculated that Mount Abu was the original home of the Parmars. Based on the Harsol copper plates and Ain-i-Akbari, D. C. Ganguly believed they came from the Deccan region.

The earliest of the Parmar inscriptions (that of Siyaka II) have all been discovered in Gujarat, and concern land grants in that region. Based on this, D. B. Diskalkar and H. V. Trivedi theorized that the Parmars were associated with Gujarat during their early days. Another possibility is that the early Parmar rulers temporarily left their capital city of Dhara in Malwa for Gujarat because of a Gurjara-Pratihara invasion. This theory is based on the combined analysis of two sources: the Nava-sahasanka-charita, which states that the Parmar king Vairisimha cleared the Dhara city in Malwa of enemies; and the 945-946 CE Pratapgah inscription of the Gurjara-Prathiara king Mahendrapala, which states that he recaptured Malwa.

Early

rulers :

Siyaka is the earliest known Parmar king attested by his own inscriptions. His Harsol copper plate inscription (949 CE) is the earliest available Parmar inscription: it suggests that he was a vassal of the Rashtrakuts. The list of his predecessors varies between accounts :

List of early Parmar rulers according to different sources :

Parmar is the dynasty's mythical progenitor, according to the Agnikul legend. Whether the other early kings mentioned in the Udaipur Prashasti are historical or fictional is a topic of debate among historians.

According to C. V. Vaidya and K. A. Nilakantha Sastri, the Parmar dynasty was founded only in the 10th century CE. Vaidya believes that the kings such as Vairisimha I and Siyaka I are imaginary, duplicated from the names of later historical kings in order to push back the dynasty's age. The 1274 CE Mandhata copper-plate inscription of Jayavarman II similarly names eight successors of Parmar as Kamandaludhar, Dhumraj, Devasimhapal, Kanakasimha, Shriharsh, Jagaddev, Sthirakaya and Voshari: these do not appear to be historical figures. HV Trivedi states that there is a possibility that Vairisimha I and Siyaka I of the Udaipur Prashasti are same as Vairisimha II and Siyaka II; the names might have been repeated by mistake. Alternatively, he theorizes that these names have been omitted in other inscriptions because these rulers were not independent sovereigns.

Several other historians believe that the early Parmar rulers mentioned in the Udaipur Prashasti are not fictional, and the Parmars started ruling Malwa in the 9th century (as Rashtrakut vassals). K. N. Seth argues that even some of the later Parmar inscriptions mention only 3-4 predecessors of the king who issued the inscription. Therefore, the absence of certain names from the genealogy provided in the early inscriptions does not mean that these were imaginary rulers. According to him, the mention of Upendra in Nava-Sahasanka-Charitra (composed by the court poet of the later king Sindhuraja) proves that Upendra is not a fictional king. Historians such as Georg Bühler and James Burgess identify Upendra and Krishnaraj as one person, because these are synonyms (Upendra being another name of Krishna). However, an inscription of Siyaka's successor Munj names the preceding kings as Krishnaraja, Vairisimha, and Siyaka. Based on this, Seth however identifies Krishnaraja with Vappairaj or Vakpati I mentioned in the Harsol plates (Vappairaj appears to be the Prakrit form of Vakpati-raj). In his support, Seth points out that Vairisimha has been called Krishna-padanudhyata in the inscription of Munja i.e. Vakpati II. He theorizes that Vakpati II used the name "Krishnaraj" instead of Vakpati I to identify his ancestor, in order to avoid confusion with his own name.

The imperial Parmars :

The Bhojeshwar Temple, Bhojpur

Detail of the masonry of the northern dam at Bhojpur The first independent sovereign of the Parmar dynasty was Siyaka (sometimes called Siyaka II to distinguish him from the earlier Siyaka mentioned in the Udaipur Prashasti). The Harsola copper plates (949 CE) suggest that Siyaka was a feudatory of the Rashtrakut ruler Krishna III in his early days. However, the same inscription also mentions the high-sounding Maharajadhirajapati as one of Siyaka's titles. Based on this, K. N. Seth believes that Siyaka's acceptance of the Rashtrakut lordship was nominal.

As a Rashtrakut feudatory, Siyaka participated in their campaigns against the Pratiharas. He also defeated some Huna chiefs ruling to the north of Malwa. He might have suffered setbacks against the Chandela king Yashovarman. After the death of Krishna III, Siyaka defeated his successor Khottiga in a battle fought on the banks of the Narmada River. He then pursued Khottiga's retreating army to the Rashtrakut capital Manyakheta, and sacked that city in 972 CE. His victory ultimately led to the decline of the Rashtrakuts, and the establishment of the Parmars as an independent sovereign power in Malwa.

Siyaka's successor Munja achieved military successes against the Chahamanas of Shakambari, the Chahamanas of Naddula, the Guhilas of Mewar, the Hunas, the Kalachuris of Tripuri, and the ruler of Gurjara region (possibly a Gujarat Chaulukya or Pratihara ruler). He also achieved some early successes against the Western Chalukya king Tailapa II, but was ultimately defeated and killed by Tailapa some time between 994 CE and 998 CE.

As a result of this defeat, the Parmars lost their southern territories (possibly the ones beyond the Narmada river) to the Chalukyas. Munja was reputed as a patron of scholars, and his rule attracted scholars from different parts of India to Malwa. He was also a poet himself, although only a few stanzas composed by him now survive.

Munja's brother Sindhuraj (ruled c. 990s CE) defeated the Western Chalukya king Satyashraya, and recovered the territories lost to Tailap II. He also achieved military successes against a Hun chief, the Somvanshi of south Kosal, the Shilaharas of Konkan, and the ruler of Lata (southern Gujarat). His court poet Padmagupt wrote his biography Nav-Sahasank-Charit, which credits him with several other victories, although these appear to be poetic exaggerations.

Sindhuraj's son Bhoj is the most celebrated ruler of the Parmar dynasty. He made several attempts to expand the Parmar kingdom varying results. Around 1018 CE, he defeated the Chalukyas of Lata in present-day Gujarat. Between 1018 CE and 1020 CE, he gained control of the northern Konkan, whose Shilahara rulers probably served as his feudatories for a brief period. Bhoj also formed an alliance against the Kalyani Chalukya king Jayasimha II, with Rajendra Chola and Gangeya-deva Kalachuri. The extent of Bhoj's success in this campaign is not certain, as both Chalukya and Parmar panegyrics claimed victory. During the last years of Bhoj's reign, sometime after 1042 CE, Jayasimha's son and successor Someshvara I invaded Malwa, and sacked his capital Dhara. Bhoj re-established his control over Malwa soon after the departure of the Chalukya army, but the defeat pushed back the southern boundary of his kingdom from Godavari to Narmada.

Bhoj's attempt to expand his kingdom eastwards was foiled by the Chandela king Vidyadhar. However, Bhoj was able to extend his influence among the Chandel feudatories, the Kachchhapaghats of Dubkund. Bhoj also launched a campaign against the Kachchhapaghats of Gwalior, possibly with the ultimate goal of capturing Kannauj, but his attacks were repulsed by their ruler Kirtiraja. Bhoj also defeated the Chahamans of Shakambhari, killing their ruler Viryarama. However, he was forced to retreat by the Chahamans of Naddul. According to medieval Muslim historians, after sacking Somnath, Mahmud of Ghazni changed his route to avoid confrontation with a Hindu king named Param Dev. Modern historians identify Param Dev as Bhoj: the name may be a corruption of Parmar-Deva or of Bhoj's title Parmeshvar-Paramabhattarak. Bhoj may have also contributed troops to support the Kabul Shahi ruler Anandapala's fight against the Ghaznavids. He may have also been a part of the Hindu alliance that expelled Mahmud's governors from Hansi, Thanesar and other areas around 1043 CE. During the last year of Bhoj's reign, or shortly after his death, the Chaulukya king Bhima I and the Kalachuri king Karna attacked his kingdom. According to the 14th century author Merutung, Bhoj died of a disease at the same time the allied army attacked his kingdom.

At its zenith, Bhoj's kingdom extended from Chittor in the north to upper Konkan in the south, and from the Sabarmati River in the west to Vidisha in the east. He was recognized as a capable military leader, but his territorial conquests were short-lived. His major claim to fame was his reputation as a scholar-king, who patronized arts, literature and sciences. Noted poets and writers of his time sought his sponsorship. Bhoj was himself a polymath, whose writings cover a wide variety of topics include grammar, poetry, architecture, yoga, and chemistry. Bhoj established the Bhoj Shal which was a centre for Sanskrit studies and a temple of Sarasvati in present-day Dhar. He is said to have founded the city of Bhojpur, a belief supported by historical evidence. Besides the Bhojeshwar Temple there, the construction of three now-breached dams in that area is attributed to him. Because of his patronage to literary figures, several legends written after his death featured him as a righteous scholar-king. In terms of the number of legends centered around him, Bhoj is comparable to the fabled Vikramaditya.

Decline :

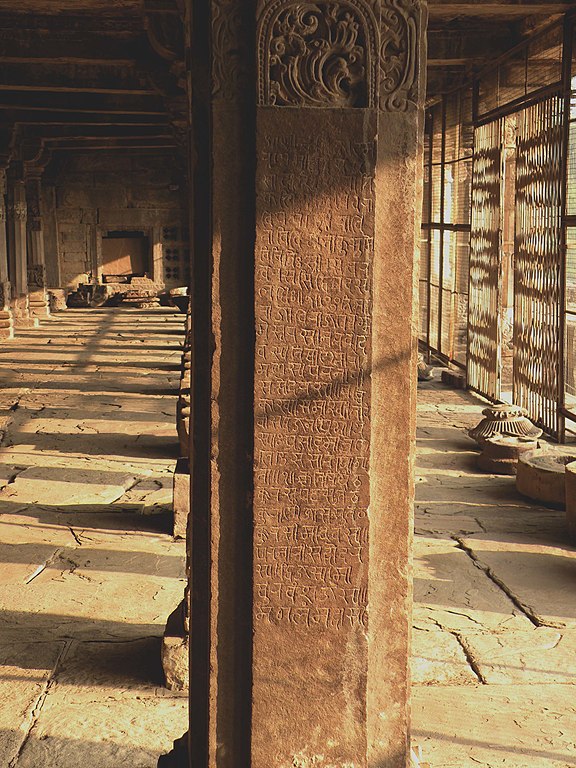

Pillar in the Bijamandal, Vidisha with an inscription of Naravarman

Fragments of the Dhar iron pillar attributed to the Parmars Bhoj's successor Jaysimha I, who was probably his son, faced the joint Kalachuri-Chaulukya invasion immediately after Bhoj's death. Bilhan's writings suggest that he sought help from the Chalukyas of Kalyani. Jayasimha's successor and Bhoj's brother Udayaditya was defeated by Chamundaraj, his vassal at Vagad. He repulsed an invasion by the Chaulukya ruler Karna, with help from his allies. Udayaditya's eldest son Lakshmadev has been credited with extensive military conquests in the Nagpur Prashasti inscription of 1104-05 CE. However, these appear to be poetic exaggerations. At best, he might have defeated the Kalachuris of Tripuri. Udayaditya's younger son Naravarman faced several defeats, losing to the Chandelas of Jejakabhukti and the Chaulukya king Jayasimha Siddharaj. By the end of his reign, one Vijayapala had carved out an independent kingdom to the north-east of Ujjain.

Yashovarman lost control of the Parmar capital Dhara to Jaysimha Siddharaj. His successor Jayavarman I regained control of Dhara, but soon lost it to an usurper named Ballala. The Chaulukya king Kumarpal defeated Ballal around 1150 CE, supported by his feudatories the Naddul Chahaman ruler Alhan and the Abu Parmar chief Yashodhaval. Malwa then became a province of the Chaulukyas. A minor branch of the Parmars, who styled themselves as Mahakumaras, ruled the area around Bhopal during this time. Nearly two decades later, Jayavarman's son Vindhyavarman defeated the Chaulukya king Mularaj II, and re-established the Parmar sovereignty in Malwa. During his reign, Malwa faced repeated invasions from the Hoysals and the Yadavs of Devagiri. He was also defeated by the Chaulukya general Kumar. Despite these setbacks, he was able to restore the Parmar power in Malwa before his death.

Vindhyavarman's son Subhatavarman invaded Gujarat, and plundered the Chaulukya territories. But he was ultimately forced to retreat by the Chaulukya feudatory Lavan-Prasad. His son Arjunvarman I also invaded Gujarat, and defeated Jayant-simha (or Jay-simha), who had usurped the Chaulukya throne for a brief period. He was defeated by Yadav general Kholeshvar in Lata.

Arjunvarman was succeeded by Devpal, who was the son of Harishchandra, a Mahakumar (chief of a Parmar branch). He continued to face struggles against the Chaulukyas and the Yadavs. The Sultan of Delhi Iltutmish captured Bhilsa during 1233-34 CE, but Devpal defeated the Sultanate's governor and regained control of Bhilsa. According to the Hammir Mahakavya, he was killed by Vagbhat of Ranthambhor, who suspected him of plotting his murder in connivance with the Delhi Sultan.

During the reign of Devpal's son Jaitugidev, the power of the Parmars greatly declined because of invasions from the Yadav king Krishna, the Delhi Sultan Balban, and the Vaghela prince Visal-dev. Devpal's younger son Jayvarman II also faced attacks from these three powers. Either Jaitugi or Jayvarman II moved the Parmar capital from Dhara to the hilly Mandap-Durga (present-day Mandu), which offered a better defensive position.

Arjunvarman II, the successor of Jayvarman II, proved to be a weak ruler. He faced rebellion from his minister. In the 1270s, the Yadav ruler Ramchandra invaded Malwa, and in the 1280s, the Ranthambhor Chahamana ruler Hammir also raided Malwa. Arjun's successor Bhoj II also faced an invasion from Hammir. Bhoj II was either a titular ruler controlled by his minister, or his minister had usurped a part of the Parmar kingdom.

Mahalakdev, the last known Parmar king, was defeated and killed by the army of Alauddin Khalji in 1305 CE.

Rulers :

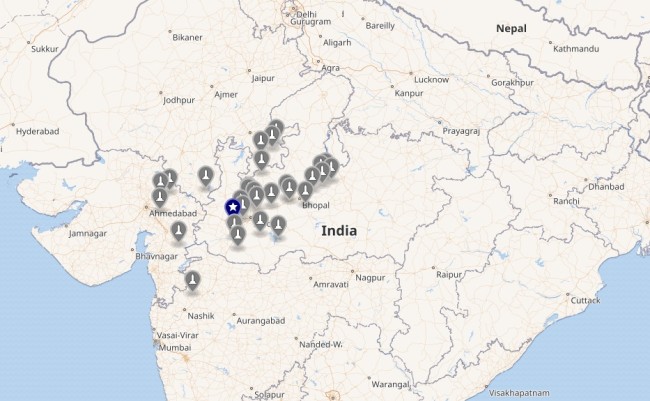

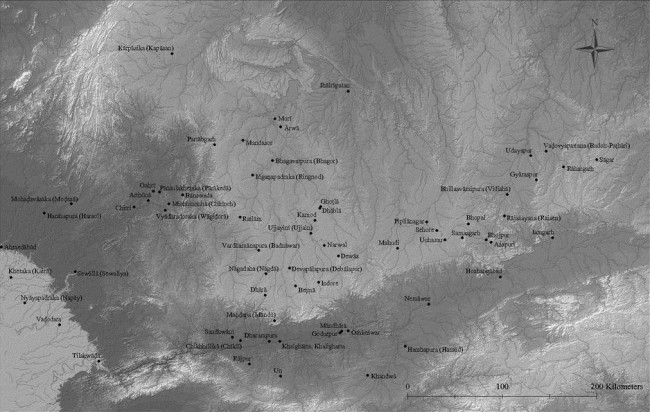

Find spots of the inscriptions from the reigns of Parmar monarchs of Malwa The Parmar rulers mentioned in the various inscriptions and literary sources are as follows. The rulers are sons of their predecessors, unless otherwise specified. [better source needed]

An inscription from Udaipur indicates that the Parmar dynasty survived until 1310, at least in the north-eastern part of Malwa. A later inscription shows that the area had been captured by the Delhi Sultanate by 1338.

Branches and claimed descendants :

Map showing the find-spots of the inscriptions of the imperial Parmars and their various branches Besides the Parmar sovereigns of Malwa, several branches of the dynasties ruled as feudatories at various places. These include :

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||