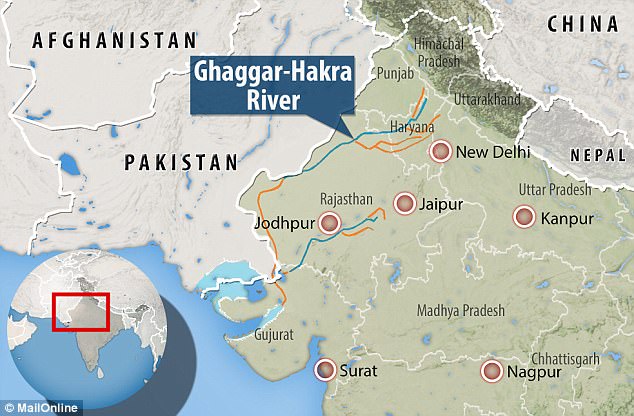

| GHAGGAR - HAKRA RIVER

Ghaggar Hakra River

Ghaggar river in Panchkula Country

: India, Pakistan

The Ghaggar-Hakra River is an intermittent river in India and Pakistan that flows only during the monsoon season. The river is known as Ghaggar before the Ottu barrage and as the Hakra downstream of the barrage. The Hakra river is hydraulically connected to the Nara River provided it has adequate flow to maintain surface flow. After the construction of the Otu Barrage, the downstream Hakra river dried up fully but subsurface flow is maintained to the Nara river which becomes later the delta channel of the Indus River before joining the sea via Kori Creek in Gujarat state.

A paper published in Nature journal in 2017 asserts that the Ghaggar-Hakra paleochannel was fed by the Himalayan Sutlej River. The initial abandonment by the river Sutlej started about 15,000 years ago, with complete avulsion to its current course shortly after 8,000 years ago.

The basin is classified in two parts, Khadir and Bangar, the higher area that is not flooded in rainy season is called Bangar and the lower flood-prone area is called Khadar.

Most sites of the Mature Harappan Civilisation (aka Indus Valley Civilisation) (2600-1900 BCE) are actually found along the (dried-out) bed of the Ghaggar-Hakkar, while the Late Harappan Civilisation was centered on the upper Ghaggar-Hakkar and the lower Indus.

Recent geophysical research shows that during the mature time of the Harappan Civilisation, the Ghaggar-Hakra system became a system of monsoon-fed rivers, after the course change of Sutlej river about 8,000 years ago. The Indus Valley Civilisation declined when the monsoons that fed the rivers diminished at around some 4,000 years ago. [note 1] Subatlantic aridification subsequently reduced the Ghaggar-Hakra to the seasonal river it is today.

Nineteenth and early 20th century scholars, but also some more recent authors, have suggested that the Ghaggar-Hakra might be the defunct remains of the Sarasvati River mentioned in the Rig Ved, fed by Himalayan-fed rivers which changed their course due to tectonics.[citation needed]

River

course :

The Ghaggar river flows into the Ottu reservoir, afterwards it becomes the Hakra river The Ghaggar is an intermittent river in India, flowing during the monsoon rains. It originates in the village of Dagshai in the Shivalik Hills of Himachal Pradesh at an elevation of 1,927 metres (6,322 ft) above mean sea level and flows through Punjab and Haryana states into Rajasthan; just southwest of Sirsa, Haryana and by the side of Talwara Lake in Rajasthan.

Dammed at Ottu barrage near Sirsa, Ghaggar feeds two irrigation canals that extend into Rajasthan.

Tributaries

of the Ghaggar :

The Kaushalya river is a tributary of Ghaggar river on the left side of Ghahhar-Hakra, it flows in the Panchkula district of Haryana state of India and confluences with Ghaggar river near Pinjore just downstream of Kaushalya Dam.

Hakra

River :

Hakra or Hakro Darya streamed through Sindh and its sign can be found in Sindh areas such as Khairpur, Nawabshah, Sanghar and Tharparkar.

Along the course of the Ghaggar-Hakra river, there are many early archaeological sites belonging to the Indus Valley Civilization; but not further south than the middle of Bahawalpur district. It has been assumed that the Sarasvati ended there in a series of terminal lakes, and some think that its water only reached the Indus or the sea in very wet rainy seasons. However, satellite images seem to contradict this: they do not show subterranean water in reservoirs in the dunes between the Indus and the end of the Hakra west of Fort Derawar/Marot. [failed verification]

Palaeogeography

:

According to Mugal the Sutlej may have flowed periodically into the Ghaggar-Hakra river bed. Mista suggested the same possibility for the Yamuna.

Analysis of sand grains using optically stimulated luminescence by Ajit Singh and others in 2017 indicated that the paleochannel of the Ghaggar-Hakra is a former course of the Sutlej, which diverted to its present course before the development of the Harappan Civilisation. The abandonment of this older course by the Sutlej started 15,000 years ago, and was complete by 8,000 years ago. Ajit Singh et al. conclude that the urban populations settled not along a perennial river, but a monsoon-fed seasonal river that was not subject to devastating floods.

Drying-up

of the Hakra :

According to M. R. Mughal, the Hakkra dried-up at the latest in 1900 BCE, but other scholars conclude that it took place much earlier. Henri-Paul Francfort, utilizing images from the French satellite SPOT two decades ago, found that the large river Sarasvati is pre-Harappan altogether, and started drying up already in the middle of the 4th millennium BCE; during Harappan times only a complex irrigation-canal network was being used. The date should therefore be pushed back to c. 3800 BCE.

Paleobotanical information documents the aridity that developed after the drying up of the river. Most of the Mature Harappan sites are located in the middle Ghaggar-Hakra river valley, and some on the Indus and in Kutch-Saurashtra. [note 2] However, just as in other contemporary cultures, such as the BMAC, settlements move up-river due to climate changes around 2000 BCE. In the late Harappan period the number of late Harappan sites in the middle Ghaggar-Hakra channel and in the Indus valley diminishes, while it expands in the upper Ghaggar-Sutlej channels and in Saurashtra.

Painted Grey Ware sites (c. 1000–600 BCE) have been found at former IVC-sites at the middle and upper Ghaggar-Hakra channel, and have also been found in the bed and not on the banks of the Ghaggar-Hakra river, which suggests that river was certainly dried up by this period. The sparse distribution of the Painted Gray Ware sites in the Ghaggar river valley indicates that during this period the Ghaggar river had already dried up.

Diminishing

of the monsoons :

Late in the 2nd millennium BCE the Ghaggar-Hakra fluvial system dried up, which affected the Harappan civilisation. Giosan et al., in their study Fluvial landscapes of the Harappan civilisation, make clear that the Ghaggar-Hakra fluvial system was not a large glacier-fed Himalayan river, but a monsoonal-fed river. [note 3] [note 4] They concluded that the Indus Valley Civilisation died out because the monsoons, which fed the rivers that supported the civilisation, diminished. With the rivers drying out as a result, the civilisation diminished some 4000 years ago. This particular effected the Ghaggar-Hakra system, which became ephemeral and was largely abandoned. The Indus Valley Civilisation had the option to migrate east toward the more humid regions of the Indo-Gangetic Plain, where the decentralized late Harappan phase took place.

Most of the Harappan sites along the Ghaggar-Hakkra are found in desert country, and have remained undisturbed since the end of the Indus Civilization. This contrasts with the heavy alluvium of the Indus and other large Panjab rivers that have obscured Harappan sites, including part of Mohenjo Daro. About 80 percent of the Ghaggar-Hakkra sites are datable to the fourth or third millennium BCE, suggesting that the river was flowing during (part of) this period, which is also indicated by the fact that some Indus sites are found inside the bed of the Ghaggar-Hakra.[citation needed]

Identification

with the Rigvedic Sarasvati River :

Rig

Ved :

The identification with the Sarasvati River is based on the mentions in Vedic texts, e.g. in the enumeration of the rivers in Rigved 10.75.05; the order is Ganga, Yamuna, Sarasvati, Sutudri, Parusni. Later Vedic texts record the river as disappearing at Vinasan (literally, "the disappearing") or Upmajjan, and in post-Vedic texts as joining both the Yamuna and Ganges as an invisible river at Prayag (Allahabad). Some claim that the sanctity of the modern Ganges is directly related to its assumption of the holy, life-giving waters of the ancient Saraswati River. The Mahabharat says that the Sarasvati River dried up in a desert (at a place named Vinasan or Adarsan).

Identification

:

More recently, but writing before Giosan's 2012 publication, several scholars have identified the old Ghaggar-Hakra River with the Vedic Sarasvati River and the Chautang with the Drishadvati River. Such scholars include Gregory Possehl, J. M. Kenoyer, Bridget and Raymond Allchin, Kenneth Kennedy, Franklin Southworth, and numerous Indian archaeologists. Gregory Possehl and Jane McIntosh refer to the Ghaggar-Hakra River as "Sarasvati" throughout their respective 2002 and 2008 books on the Indus Civilisation, and Gregory Possehl states:

"Linguistic, archaeological, and historical data show that the Sarasvati of the Veds is the modern Ghaggar or Hakra."

Because most of the Indus Valley sites known so far are actually located on the Ghaggar-Hakra river and its tributaries and not on the Indus river, some Indian archaeologists, such as S.P. Gupta, have proposed to use the term "Indus Sarasvati Civilization" to refer to the Harappan culture which is named, as is common in archaeology, after the first place where the culture was discovered.

Tectonics

:

Anthropologists Gregory Possehl (1942–2011), J. M. Kenoyer, and professional archaeological writer, Jane McIntosh, have suggested that many religious and literary invocations to Sarasvati in the Rig Ved were to a real Himalayan river, whose waters, on account of seismic events, were diverted, leaving only a seasonal river, the Ghaggar-Hakra, in the original river bed.

Objections

:

The idea that the Ghaggar-Hakra was fed by Himalayan sources has been contradicted by recent geophysical research, which shows that the Ghaggar-Hakra system, although having greater discharge in Harappan times which was enough to sustain human habitation, was not sourced by the glaciers and snows of the Himalayas, but rather by a system of perennial monsoon-fed rivers. Geologist Liviu Giosan of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and his team showed that in contrast to all Himalayan rivers in the region that dug out wide valleys in their own sediments as the monsoon declined, no such valley exists between the Sutlej and the Yamuna, demonstrating that neither the Ghaggar-Hakra nor any other Sarasvati candidate in that region had a Himalayan source. [note 1] Late Holocene aridification subsequently reduced the Ghaggar-Hakra to the seasonal river it is today. [note 9] Clift et al. (2012), using dating of zircon sand grains, have shown that subsurface river channels near the Indus Valley Civilisation sites in Cholistan immediately below the dry Ghaggar-Hakra bed show sediment affinity not with the Ghagger-Hakra, but instead with the Beas River in the western sites and the Sutlej and the Yamuna in the eastern ones, further weakening the hypothesis that the Ghaggar-Hakra was once a large river, but suggesting that the Yamuna itself, or a channel of the Yamuna, along with a channel of the Sutlej may have flowed west some time between 47,000 BCE and 10,000 BCE, well before the beginnings of Indus civilization.

Ajit Singh et al. (2017) show that the paleochannel of the Ghaggar-Hakra is a former course of the Sutlej, which diverted to its present course between 15,000 and 8,000 years ago, well before the development of the Harappan civilisation. Ajit Singh et al. conclude that the urban populations settled not along a perennial river, but a monsoon-fed seasonal river that was not subject to devastating floods.

Rajesh Kocchar further notes that, even if the Sutlej and the Yamuna had drained into the Ghaggar during Vedic period, it still would not fit the Rig Vedic descriptions because "the snow-fed Satluj and Yamuna would strengthen [only the] lower Ghaggar. [The] upper Ghaggar would still be as puny as it is today."

Helmand

River :

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |