| INDUS - MESOPOTAMIA RELATIONS

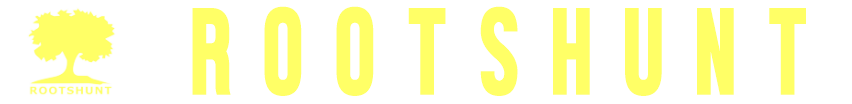

Trade routes between Mesopotamia and the Indus would have been significantly shorter due to lower sea levels in the 3rd millennium BCE

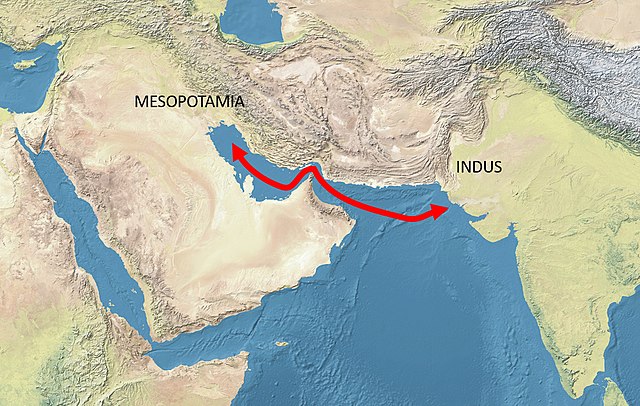

Impression of a cylinder seal of the Akkadian Empire, with label: "The Divine Sharkalisharri Prince of Akkad, Ibni-Sharrum the Scribe his servant". The long-horned water buffalo depicted in the seal is thought to have come from the Indus Valley, and testifies to exchanges with Meluhha, the Indus Valley civilization. Circa 2217–2193 BCE. Louvre Museum, reference AO 22303.

Indus–Mesopotamia relations are thought to have developed during the second half of 3rd millennium BCE, until they came to a halt with the extinction of the Indus valley civilization after around 1900 BCE. Mesopotamia had already been an intermediary in the trade of lapis lazuli between South Asia and Egypt since at least about 3200 BCE, in the context of Egypt-Mesopotamia relations.

Neolithic

expansion (9000–6500 BCE) :

Fertility figurine of the Halaf culture, Mesopotamia, 6000–5100 BCE. Louvre

Fertility figurine from Mehrgarh, Indus Valley, c.3000 BCE

Neolithic fertility goddesses in Mehrgarh are similar to those of

the Near-East. They are all part of the Neolithic ‘Venus figurines’

tradition, the abundant breasts and hips of these figurines suggest

links to fertility and procreation.

The Near-Eastern origin of South Asian agriculture is generally accepted, and it has been the "virtual archaeological dogma for decades". Gregory Possehl however argues for a more nuanced model, in which the early domestication of plant and animal species may have occurred in a wide area from the Mediterranean to the Indus, in which new technology and ideas circulated fast and were widely shared. Today, the main objection to this model lies in the fact that wild wheat has never been found in South Asia, suggesting that either wheat was first domesticated in the Near-East from well-known domestic wild species and then brought to South Asia, or that wild wheat existed in the past in South Asia but somehow became extinct without leaving a trace.

Jean-François Jarrige argues for an independent origin of Mehrgarh. Jarrige notes "the assumption that farming economy was introduced full-fledged from Near-East to South Asia," [c] and the similarities between Neolithic sites from eastern Mesopotamia and the western Indus valley, which are evidence of a "cultural continuum" between those sites. But given the originality of Mehrgarh, Jarrige concludes that Mehrgarh has an earlier local background," and is not a "'backwater' of the Neolithic culture of the Near East."

Land and maritime relations :

Global sea levels and vegetation during the Last Ice Age. The coastline was still roughly similar in about 10,000 BCE

The Indus Valley Civilization extended westward as far as the Harappan trading station of Sutkagan Dor Sea levels have been rising about 100 meters over the last 15,000 years until modern times, with the effect that coast lines have been receding vastly. This is especially the case of the coast lines of the Indus and Mesopotamia, which were originally only separated by a distance of about 1000 kilometers, compared to 2000 kilometers today. For the ancestors of the Sumerians, the distance between the coasts of the Mesopotamian area and the Indus area would have been much shorter than it is today. In particular the Persian Gulf, which is only about 30 meters deep today, would have been at least partially dry, and would have formed an extension of the Mesopotamian basin.

Sea-going vessel with direction finding birds to find land. Model of Mohenjo-Daro seal, 2500-1750 BCE The westernmost Harappan city was located on the Makran coast at Sutkagan Dor, near the tip of the Arabian peninsula, and is considered as an ancient maritime trading station, probably between India and the Persian Gulf.

Sea-going vessels were known in the Indus region, as shown by seals showing ships with land-finding birds (disha-kaka), dating to 2500-1750 BCE. When a boat was lost at sea, with land beyond the horizon, birds released by the mariners would securely fly back to land, and therefore show the boats the way to safety. Various stamp seals are known from the Indus and the Persian Gulf area, with depictions of large ships pertaining to different shipbuilding traditions. Sargon of Akkad (c. 2334–2284 BCE) claimed in one of his inscriptions that "ships from Meluhha, Magan and Dilmun made fast at the docks of Akkad".

Commercial

and cultural exchanges :

Indus imports into Mesopotamia :

The etched carnelian beads in this necklace from the Royal Cemetery dating to the First Dynasty of Ur (2600-2500 BCE) were probably imported from the Indus Valley Clove heads, thought to originate from the Moluccas in Maritime Southeast Asia were found in a 2nd millennium BCE site in Terqa. Evidence for imports from the Indus to Ur can be found from around 2350 BCE. Various objects made with shell species that are characteristic of the Indus coast, particularly Trubinella Pyrum and Fasciolaria Trapezium, have been found in the archaeological sites of Mesopotamia dating from around 2500-2000 BCE. Carnelian beads from the Indus were found in Ur tombs dating to 2600–2450. In particular, carnelian beads with an etched design in white were probably imported from the Indus Valley, and made according to a technique of acid-etching developed by the Harappans. Lapis Lazuli was imported in great quantity by Egypt, and already used in many tombs of the Naqada II period (circa 3200 BCE). Lapis Lazuli probably originated in northern Afghanistan, as no other sources are known, and had to be transported across the Iranian plateau to Mesopotamia, and then Egypt.

Several Indus seals with Harappan script have also been found in Mesopotamia, particularly in Ur, Babylon and Kish. The water buffalos which appears on the Akkadian cylinder seals from the time of Naram-Sin (circa 2250 BCE), may have been imported to Mesopotamia from the Indus as a result of trade.

Akkadian Empire records mention timber, carnelian and ivory as being imported from Meluhha by Meluhhan ships, Meluhha being generally considered as the Mesopotamian name for the Indus Valley.

‘The ships from Meluhha, the ships from Magan, the ships from Dilmun, he made tie-up alongside the quay of Akkad’

—

Inscription by Sargon of Akkad (ca.2270-2215 BCE)

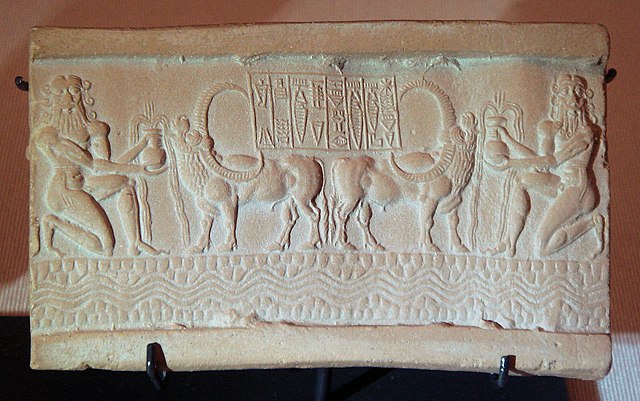

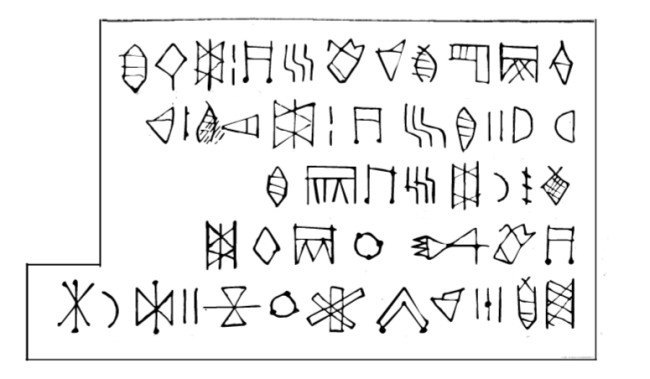

Impression of an Indus cylinder seal discovered in Susa, in strata dated to 2600-1700 BCE. Elongated buffalo with line of standard Indus script signs. Tell of the Susa acropolis. Louvre Museum, reference Sb 2425. Indus script numbering convention per Asko Parpola.

Indus Valley "Unicorn" seal and etched carnelian beads excavated in Kish by Ernest J. H. Mackay, Mesopotamia, early Sumerian period stratification, circa 3000 BCE

Indus seal impression discovered in Telloh, Mesopotamia

Indus seal found in Kish by S. Langdon. Pre-Sargonid (pre-2250 BCE) stratification

Indus round seal with impression. Elongated buffalo with Harappan script imported to Susa in 2600-1700 BCE. Found in the tell of the Susa acropolis. Louvre Museum, reference Sb 5614

Indian carnelian beads with white design, etched in white with an alkali through a heat process, imported to Susa in 2600-1700 BCE. Found in the tell of the Susa acropolis. Louvre Museum, reference Sb 17751. These beads are identical with beads found in the Indus Civilization site of Dholavira.

Indus bracelet, front and back, made of Fasciolaria Trapezium or Xandus Pyrum imported to Susa in 2600-1700 BCE. Found in the tell of the Susa acropolis. Louvre Museum, reference Sb 14473. This type of bracelet was manufactured in Mohenjo-daro, Lothal and Balakot. The back is engraved with an oblong chevron design which is typical of shell bangles of the Indus Civilization.

Indus Civilisation Carnelian bead with white design, ca. 2900–2350 BCE. Found in Nippur, Mesopotamian

Etched carnelian beads excavated in the Royal Cemetery of Ur, tomb PG 1133, 2600-2500 BCE

Indus Valley Civilization weight in veined jasper, excavated in Susa in a 12th-century BCE princely tomb. Louvre Museum Sb 17774

Similar Harappan weights found in the Indus Valley. New Delhi Museum

A rare etched carnelian bead found in Egypt, thought to have been imported from the Indus Valley Civilization through Mesopotamia. Late Middle Kingdom. London, Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, ref. UC30334.

Mesopotamian

imports into the Indus :

Uruk period Mesopotamian king as Master of Animals on the Gebel el-Arak Knife, dated circa 3300-3200 BCE. Louvre Museum, reference E 11517

Indus valley civilization seal, with man fighting two tigers (2500-1500 BC) Bull-man fighting beast :

Enkidu fighting a lion, Akkadian Empire seal, Mesopotamia, circa 2200 BCE

Fighting scene between a beast and a man with horns, hooves and a tail, who has been compared to the Mesopotamian bull-man Enkidu. Indus Valley Civilization seal

Possible iconographical influences :

There are also many instances influence the other way round, in which Indus Valley seals and designs have been found in Mesopotamia.

Indus

Valley stamp seals :

Several Indus Valley seals show a fighting scene between a tiger-like beast and a man with horns, hooves and a tail, who has been compared to the Mesopotamian bull-man Enkidu, also a partner of Gilgamesh, and suggests a transmission of Mesopotamian mythology.

Cylinder

seals :

Others have noted the cylinder seals showing Indus valley's influence on Mesopotamia. On other hands, they were in response to the overland trade between the two cultures.

Sumerian cylinder seal with two long-horned antelopes with a tree or bush in front, excavated in Kish, Mesopotamia

A rare Indus Valley civilization cylinder seal composed of two animals with a tree or bush in front. Such cylinder seals are indicative of contacts with Mesopotamia

Horned deity with one-horned attendants on an Indus Valley seal. Horned deities are a standard Mesopotamian theme. 2000-1900 BCE. Islamabad Museum Indian

genes in ancient Mesopotamia :

Methodology :

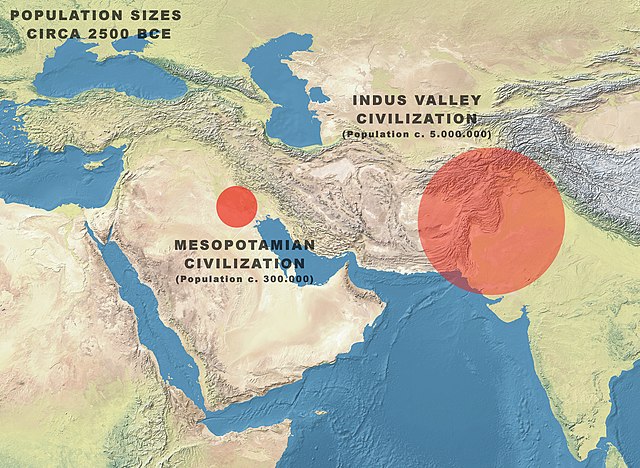

Comparative population sizes circa 2500 BCE A genetic analysis of the ancient DNA of Mesopotamian skeletons was made on the excavated remains of four individuals from ancient tombs in Tell Ashara (ancient Terqa) and Tell Masaikh (near Terqa, also known as ancient Kar-Assurnasirpal), both in the middle Euphrates valley in the east of modern Syria. The two oldest skeletons were dated to 2,650-2,450 BCE and 2,200-1,900 BCE respectively, while the two younger skeletons were dated to circa 500 AD. All the studied individuals carried mtDNA haplotypes corresponding to the M4b1, M49 and/or M61 haplogroups, which are believed to have arisen in the area of the Indian subcontinent during the Upper Paleolithic, and are absent in people living today in Syria. These haplogroups are still present in people inhabiting today's Tibet, Himalayas (Ladakh), India and Pakistan, and are restricted today to the South, East and Southeast Asia regions. The data suggests a genetic link of the region with the Indian subcontinent in the past that has not left traces in the modern population of Mesopotamia.

Other studies have also shown connections between the populations of Mesopotamia and population groups now located in Southern India, such as the Tamils.

Analysis :

Sculpture of the head of Sumerian ruler Gudea, c. 2150 BC The genetic analysis suggests that a continuity existed between Trans-Himalaya and Mesopotamia regions in ancient time, and that the studied individuals represent genetic associations with the Indian subcontinent. It is likely that this genetical connection was broken as a result of population movements during more recent times.

The fact that the studied individuals comprised both males and a female, each living in a different period and representing different haplotypes, suggests that the nature of their presence in Mesopotamia was long-lasting rather than incidental. The close ancestors of the specimens could fall within the population founding Terqa, a historical site that probably constructed during the early Bronze Age, at a time only slightly preceding the dating of the skeletons.

The studied individuals could also have been the descendants of much earlier migration waves who brought these genes from the Indian subcontinent. It cannot be excluded that among them were people involved in the founding of the Mesopotamian civilizations. For instance, it is commonly accepted that the founders of Sumerian civilization may have come from outside the region, but their exact origin is still a matter of debate. The migrants could have entered Mesopotamia earlier than 4,500 years ago, during the lifetime of the oldest studied individual. Alternatively, the studied individuals may have belonged to groups of itinerant merchants moving along a trade route passing near or through the region.

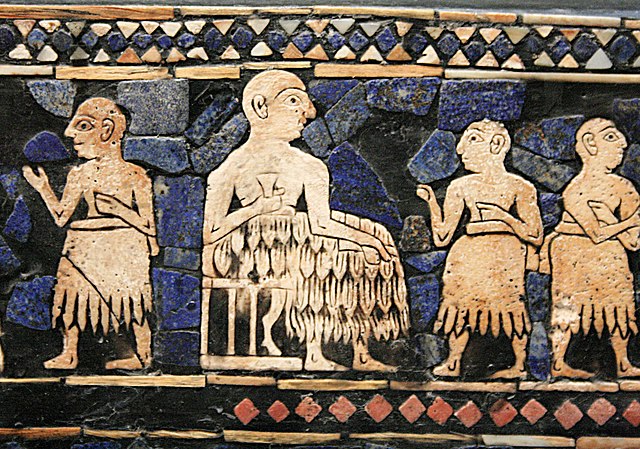

Enthroned Sumerian king of Ur, with attendants. Standard of Ur, c. 2600 BCE

Sumerian prisoners on a victory stele of Akkadian king Sargon, circa 2300 BCE. Louvre Museum

Portrait of Summerian ruler Ur-Ningirsu, son of Gudea, c.2100 BCE. Louvre Museum

Sumerian princess of the time of Gudea circa 2150 BCE

Scripts and languages : Mesopotamian

"Meluhha" seal :

The seal

Meluhha

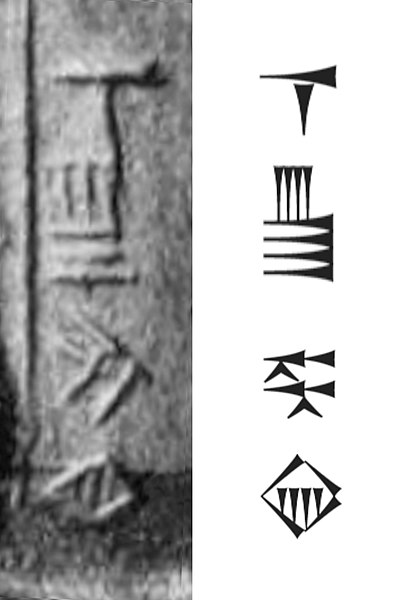

Akkadian Empire cylinder seal with inscription: "Shu-ilishu,

interpreter of the language of Meluhha" (Me-luh-haKI, "KI"

standing for "country"). Louvre Museum, reference AO 22310.

The Meluhhan language was not readily understandable at the Akkadian court, since interpretators of the Meluhhan language are known to have resided in Mesopotamia, particularly through an Akkadian seal with the inscription "Shu-ilishu, interpreter of the Meluhhan language".

Linear Elamite inscription the "Table of the Lion", time of king Kutik-Inshushinak, Louvre Museum Sb 17

Transcription of the "Table of the Lion" Linear Elamite text

A seal with an inscription in the Indus script Chronology :

Indus-type statuette, found in Susa in the 2600-1700 BCE site of the Tel of the Acropolis at Susa. Louvre Museum, reference Sb 80 Etched carnelian beads :

Indus valley civilization etched carnelian bead, Mohenjo-daro

Etched carnelian bead excavated in Susa, dated 2600-1700 BCE Sargon of Akkad (circa 2300 or 2250 BCE), was the first Mesopotamian ruler to make an explicit reference to the region of Meluhha, which is generally understood as being the Baluchistan or the Indus area. Sargon mentions the presence of Meluhha, Magan, and Dilmun ships at Akkad.

These dates correspond roughly to the Mature Harappan phase, dated from around 2600 to 2000 BCE. The dates for the main occupation of Mohenjo-Daro are about Mohenjo-daro from 2350 to 2000/1900 BCE.

It has been suggested that the early Mesopotamian Empire preceded the emergence of the Harappan civilization, and that trade and cultural exchanges may have facilitated the emergence of Harappan culture. Alternatively, it is possible that the Harappan culture had already emerged by the time trade with Mesopotamia started. Uncertainties in dating make it impossible to establish a clear order at this stage.

Exchanges seem to have been most significant during the Akkadian Empire and Ur III periods, and to have waned afterwards together with the disappearance of the Indus valley civilization.

Comparative

sizes :

There were altogether about 1,500 Indus valley cities, amounting to a population of perhaps 5 million at the maximum time of their florescence. In contrast, the total population of Mesopotamia in 2,500 BCE was around 290,000.

Large-scale exchanges recovered with the Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley, circa 500 BCE.

Views

of cultural diffusion :

https://en.wikipedia.org |

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)