| INDUS SCRIPT

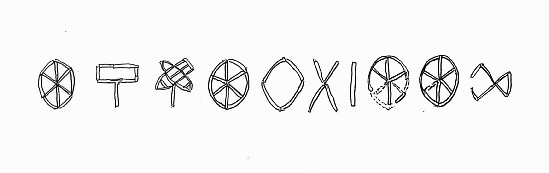

Seal impression showing a typical inscription of five characters 3500 – 1900 BCE

Unicorn seal of Indus Valley, Indian Museum

Collection of seals The Indus script (also known as the Harappan script) is a corpus of symbols produced by the Indus Valley Civilization. Most inscriptions containing these symbols are extremely short, making it difficult to judge whether or not these symbols constituted a script used to record a language, or even symbolise a writing system. In spite of many attempts, the 'script' has not yet been deciphered, but efforts are ongoing. There is no known bilingual inscription to help decipher the script, and the script shows no significant changes over time. However, some of the syntax (if that is what it may be termed) varies depending upon location.

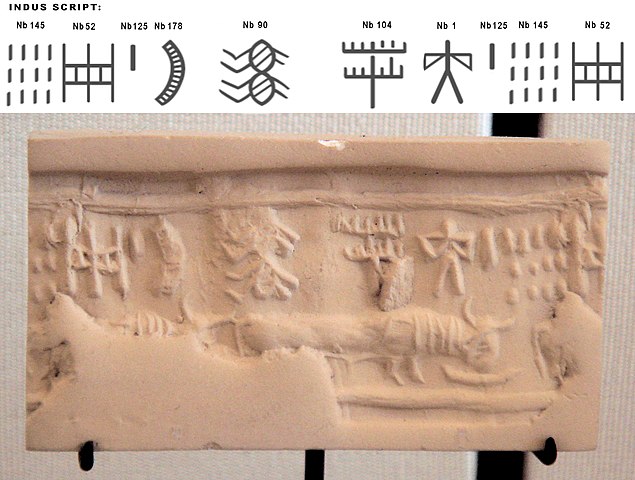

The first publication of a seal with Harappan symbols dates to 1875, in a drawing by Alexander Cunningham. Since then, over 4,000 inscribed objects have been discovered, some as far afield as Mesopotamia, as a consequence of ancient Indus-Mesopotamia relations. In the early 1970s, Iravatham Mahadevan published a corpus and concordance of Indus inscriptions listing 3,700 seals and 417 distinct signs in specific patterns. He also found that the average inscription contained five symbols and that the longest inscription contained only 26 symbols.

Some scholars, such as G.R. Hunter, S. R. Rao, John Newberry and Krishna Rao have argued that the Brahmi script has some connection with the Indus system. F. Raymond Allchin has somewhat cautiously supported the possibility of the Brahmi script being influenced by the Indus script. Another possibility for continuity of the Indus tradition is in the megalithic culture graffiti symbols of southern and central India (and Sri Lanka), which probably do not constitute a linguistic script but may have some overlap with the Indus symbol inventory. Linguists such as Iravatham Mahadevan, Kamil Zvelebil and Asko Parpola have argued that the script had a relation to a Dravidian language.

Corpus :

Early examples of the symbol system are found in an Early Harappan and Indus civilisation context, dated to possibly as early as the 35th century BCE. In the Mature Harappan period, from about 2600 BCE to 1900 BCE, strings of Indus signs are commonly found on flat, rectangular stamp seals as well as many other objects including tools, tablets, ornaments and pottery. The signs were written in many ways, including carving, chiseling, painting and embossing, on objects made of many different materials, such as soapstone, bone, shell, terracotta, sandstone, copper, silver and gold. Often, animals such as bulls, elephants, rhinoceros, water buffaloes and the mythical unicorn accompanied the text on seals to help the illiterate identify the origin of a particular seal.

Late

Harappan :

During an underwater excavation at the Late Harappan site of Bet Dwarka, a seven sign inscription was discovered inscribed on a pottery jar. The inscription is dated to 1528 BCE and consists of linear signs, as compared to the logographic Indus script. According to S.R Rao, four out of the seven signs show similarities with the Brahmi letters cha, ya, ja, pa or sa respectively. The script is also written from left to right, as is the case with Brahmi.

Jhukar Phase, Sindh

Jhukar phase is the late Harappan phase in the present province of Sindh, Pakistan which followed the mature urbanized Harappan phase. Although seals from this phase lack the Indus script which characterized the preceding phase of the civilization, some potsherd inscriptions have been noted.

Daimabad, Maharashtra

Indus inscribed seals and potsherds have been noted at Daimabad in its late Harappan and Daimabad phase dated 2200-1600 BC.

Characteristics

:

Decipherability question :

Indus script tablet recovered from Khirasara, Indus Valley Civilization

Ten Indus script from the northern gate of Dholavira, dubbed the Dholavira Signboard, one of the longest known sequences of Indus characters An opposing hypothesis that has been offered by Michael Witzel and Steve Farmer, is that these symbols are nonlinguistic signs, which symbolise families, clans, gods, and religious concepts and are similar to components of coats of arms or totem poles. In a 2004 article, Farmer, Sproat, and Witzel presented a number of arguments stating that the Indus script is nonlinguistic. The main ones are the extreme brevity of the inscriptions, the existence of too many rare signs (which increase over the 700-year period of the Mature Harappan civilization) and the lack of the random-looking sign repetition that is typical of language.

Asko Parpola, reviewing the Farmer, Sproat, and Witzel thesis in 2005, stated that their arguments "can be easily controverted". He cited the presence of a large number of rare signs in Chinese and emphasised that there was "little reason for sign repetition in short seal texts written in an early logo-syllabic script". Revisiting the question in a 2007 lecture, Parpola took on each of the 10 main arguments of Farmer et al., presenting counterarguments for each.

A 2009 paper published by Rajesh P N Rao, Iravatham Mahadevan and others in the journal Science also challenged the argument that the Indus script might have been a nonlinguistic symbol system. The paper concluded that the conditional entropy of Indus inscriptions closely matched those of linguistic systems like the Sumerian logo-syllabic system, Rig Vedic Sanskrit etc., but they are careful to stress that by itself does not imply that the script is linguistic. A follow-up study presented further evidence in terms of entropies of longer sequences of symbols beyond pairs. However, Sproat claimed that there existed a number of misunderstandings in Rao et al., including a lack of discriminative power in their model, and argued that applying their model to known non-linguistic systems such as Mesopotamian deity symbols produced similar results to the Indus script. Rao et al.'s argument against Sproat's claims and Sproat's reply were published in Computational Linguistics in December 2010. The June 2014 issue of Language carries a paper by Sproat that provides further evidence that the methodology of Rao et al. is flawed. Rao et al.'s rebuttal of Sproat's 2014 article and Sproat's response are published in the December 2015 issue of Language.

Attempts

at decipherment :

•

The underlying language has not been identified, though some 300

loanwords in the Rigveda are a good starting point for comparison.

Dravidian hypothesis :

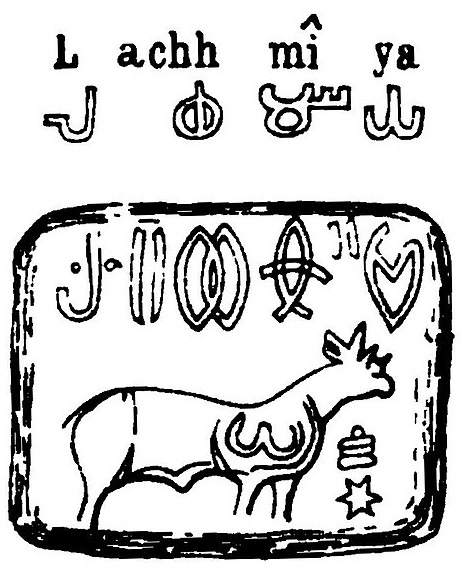

A proposed connection between the Brahmi and Indus scripts, made in the 19th century by Alexander Cunningham The Russian scholar Yuri Knorozov suggested, based on computer analysis, a Dravidian language as the most likely candidate for the underlying language of the script. Knorozov's suggestion was preceded by the work of Henry Heras, who also suggested several readings of signs based on a proto-Dravidian assumption.

The Finnish scholar Asko Parpola wrote that the Indus script and Harappan language "most likely belonged to the Dravidian family". Parpola led a Finnish team in the 1960s-80s that, like Knorozov's Soviet team, worked towards investigating the inscriptions using computer analysis. Based on a proto-Dravidian assumption, the teams proposed readings of many signs. A number of people agreed with the suggested readings of Heras and Knorozov. One such reading was legitimised when the Dravidian word for both 'fish' and 'star', "min" was hinted at through drawings of both the things together on Harappan seals. A comprehensive description of Parpola's work until 1994 is given in his book Deciphering the Indus Script.

Iravatham Mahadevan, another scholar who supported the Dravidian hypothesis, said "we may hopefully find that the proto-Dravidian roots of the Harappan language and South Indian Dravidian languages are similar. This is a hypothesis [...] But I have no illusions that I will decipher the Indus script, nor do I have any regret". Commenting on his 2014 publication Dravidian Proof of the Indus Script via The Rig Ved: A Case Study, Mahadevan claimed to have made significant progress in deciphering the script as Dravidian. According to Mahadevan, a stone celt discovered in Mayiladuthurai (Tamil Nadu) has the same markings as that of the symbols of the Indus script. The celt dates to early 2nd millennium BCE, post-dating Harappan decline. Mahadevan considered this as evidence of the same language being used by the neolithic people of south India and the late Harappans. This hypothesis was also supported by Rajesh P. N. Rao.

In May 2007, the Tamil Nadu Archaeology Department found pots with arrow-head symbols during an excavation in Melaperumpallam near Poompuhar. These symbols are claimed to have a striking resemblance to seals unearthed in Mohenjo-daro in present-day Pakistan in the 1920s. In Sembiyankandiyur a stone axe was found, claimed to be containing Indus symbols. In 2014, a cave in Kerala was discovered with 19 pictograph symbols claimed to be containing Indus writing.

In 2019, excavations at the Keezhadi site near present-day Madurai unearthed potsherds with graffiti. In a report, the Tamil Nadu Archaeology Department (TNAD) dated the potsherds to 580 BCE and said the graffiti bore numerous similarities to known Harappan symbols, so it could be a transitional script between Indus Valley script and the Tamil Brahmi script used during the Sangam Period. However, other Indian archaeologists have contested the TNAD report's claims, because the report does not say if the sherds with the Tamil-Brahmi script had been taken from the same layers as the samples that had been dated to the sixth century BC. As for the report's claim that the Keezhadi potsherds bore a script that bridged the gap between the Indus script and Tamil Brahmi, G.R.Hunter pointed out the similarities between the Indus and Brahmi scripts, in 1934, long before the Keezhadi site was discovered.

Sanskritic

hypothesis :

John E. Mitchiner dismissed some of these attempts at decipherment. Mitchiner mentioned that "a more soundly-based but still greatly subjective and unconvincing attempt to discern an Indo-European basis in the script has been that of Rao".

Miscellaneous

hypotheses :

Impression of an Indus cylinder seal discovered in Susa (modern

Iran), in strata dated to 2600-1700 BCE, an example of ancient Indus-Mesopotamia

relations. Louvre Museum, reference Sb 2425. Numbering convention

for the Indus script by Asko Parpola.

Similarities

with Linear Elamite :

Encoding

:

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |